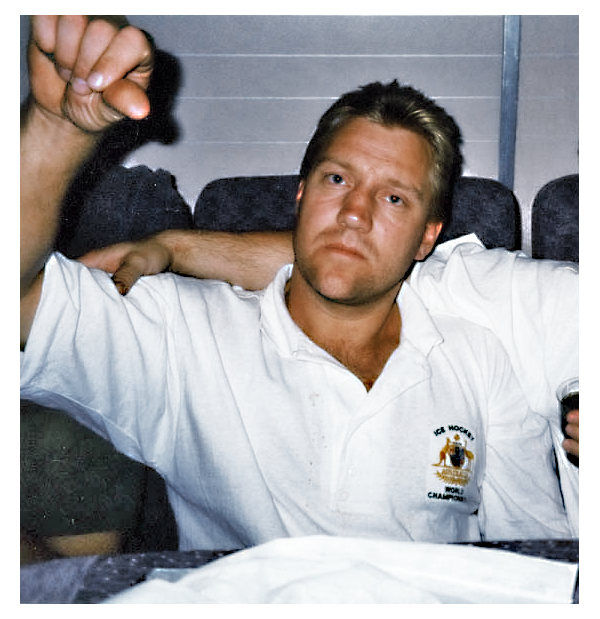

Arto Malste and Kari Pynnönen on arrival in Adelaide, Australia, 1981. Courtesy John Botterill.

THE LAKE HOUSE

Arte Malste and the hammer of the gods

We come from the land of the ice and snow

From the midnight sun where the hot springs flow.

— Immigrant Song, Robert Plant and Jimmy Page, 1970.

With Payneham Flyers IHC, Adelaide, 1981. Courtesy Steve Newbound and Frank Kutsche

With Payneham Flyers IHC, Adelaide, 1981. Courtesy Steve Newbound and Frank Kutsche

IT IS BONE-CHILLING HYPOTHERMIC, an extraordinary twenty-two below, and in the language of the man of whom I write, the snow is pyry — big, featherlight flecks falling in clumps and carpeting the ground with a layer of powdered white crystals. I respect the Finnish winter. It is a polar night, the sun below the horizon all day. At a certain point, the surface of a body of water reaches minus one point-eight. The first crystals form a temporary membrane, which the wind and waves break up into fazil ice, squeeze into a sludge of porridge ice, freeze into free-floating plates of pancake ice, and a single solid sheet eventually. In severe winters, the Baltic Sea itself may ice over almost completely. In summer, it is midnight twilight, the opposite phenomenon. Long days and white nights, the sun visible in fair weather for all twenty-four hours around the summer solstice. At its northernmost point, the sun does not set in one-quarter of the country for sixty days of summer.

In the year Jyväskylä finally became the capital of Central Finland, on the fourth day of March 1960, a son was born to Ahti and Mirjam Malste. Arte Kalevi was raised fourteen kilometres west in Vesanka, a village of thirteen hundred people founded in 1559. Sipilä, Siekkilä, Ristola and Yrjölä were the primary farms way back then, and I am not surprised to see they still exist. Malste grew up in this peaceful rural setting, in this house by a lake in the middle of a city. All around me are ponds, lakes with islands, high hills with marvellous views, spectacular forests, and fertile farmlands. The air I breathe is crisp and scented. The folk in this sparsely populated community are happy and relaxed and still gravitate to the Village Hall Rientola or the Vesanka Hall, where the library, school and kindergarten are situated, the swimming beach, most of the sports facilities, and the ice rink next to the school.

Ahti built the family farmhouse across the road from a natural ice rink for public skating. In winter, Arte skated there, its wooden change rooms operated by a full-time caretaker from the City Council. In the summer, he played soccer and pesäpallo, the national sport of Finnish baseball. It was not until the mid-1980s that ice hockey came to enjoy the same popularity as this old favourite and even surpassed it, thanks to the success of the team he was soon to join, the local JyP HP, today's JYP Jyväskylä Oy. Founded as the ice hockey section of the sports club Jyväskylän Palloilijat, the team broke away when he was sixteen.

They played at Jyväskylä jäähalli, today's Synergia-areena, in the SM-Liiga, the Finnish Elite League, which was just one division below Olympic selection standard at that time. These days, the Club has an agreement with the NHL's Boston Bruins to enable player transfer and training between the two teams and their developmental systems. It was at the top of pro hockey where a player could no longer represent more than one Club within one season, personal sponsorship was not allowed, and a quarantine system was in force to discourage trading. This perfectly paradisal hockey world that Australia's best aspire to was the world that Malste left. But we are getting ahead of ourselves.

In between house building and moose hunting, Ahti was a general foreman at a biscuit company — a Finnish Arnott's — while his mother Mirjam busied herself at the lake house. His brother Markku was a year and a half younger. For six years, Malste attended the local primary school about one kilometre from home and then went on to high school. Everything was free. His parents bought only the school bag, and he rocketed through the first dozen years of childhood on skates, practising his advanced technique all winter, any time he chose on his frozen lake. In the childhood moments he treasures, the young Malste is always skating.

At 13, in the juniors of the JyP hockey club, he played organised hockey, which meant listening to the Coach and being respectful. It meant having to learn. He and Markku played in juniors two or three times a week until one day Markku just stopped. He had no particular reason. Malste trained with winger Jari Kurri at camps and played against him in juniors. After his rookie season for Jokerit in 1977–78, Kurri scored thirty, thirty-nine the year after that, and signed with the Edmonton Oilers the one after that. (1980) Paired with Wayne Gretzky, they became one of the most prolific scoring tandems ever to play in the NHL, and Kurri powered on to win five Stanley Cups throughout a glittering career. Malste also played or trained with defenseman Risto Siltanen of Ilves, who the Oilers drafted for eight seasons in the NHL, and Reijo Ruotsalainen of Kärpät who was later twice named Finland's top defenseman and who won two Stanley Cups with the Oilers in 1987 and 1990.

In juniors, defense felt natural to Malste, and he was good in the corners. He could also read the game very well. He watched every senior game in those days, talked to the older players, listened to coaches, and mixed it with the right people. He was a student of the game, especially the theory behind gameplay. "In this situation," he explains to me, "he'll go to the boards; this one, he'll go to the centre, so reduce his scoring angle. Study the opposition, close your eyes and visualize where the puck will go". He also developed game preparation in these early years, including the obligatory rituals. "Might sound funny," he says, "but you get used to doing things a certain way, and when it works you don't change, might change your game. I always put my left sock first, then my right one. My left skate, then the right".

From the early age of sixteen, Malste continued in the Under-21 A-grade, and to properly appreciate this feat back in Australia is to understand it is equivalent to playing Australian Rules Football at the MCG at sixteen. So began the waiting game, waiting until senior players retired. Finnish hockey had started to professionalize with the founding of the Liiga in the mid-1970s, based on the NHL model. Some cities aimed to win the national championship with their players, and gradually, an increasing number of them got a side job in the sport. At seventeen, Malste did eight months of compulsory military training in the Air Force. "Really good," he confides with me, "sorted out the kids who were wandering, learnt discipline". Jyväskylä hosts the headquarters of the Finnish Air Force in Tikkakoski, about 20 kilometres north of the city centre, which meant listening to Sergeant-major and being respectful.

In 1980, over 60,000 people were living in this city. It developed rapidly in the post-war years to become the fastest-growing Finnish city of that century. Blocks of high-rise buildings replaced the wooden houses in the town centre, and entirely new suburbs rose, some several kilometres from its heart. The city itself has more buildings designed by Alvar Aalto than any other city in the world. The world famous architect had moved here with his family as a young boy in 1903 and returned to form his practice in the city after qualifying as an architect in Helsinki in 1923. Yet, lakes control the cityscape and not Aalto, one of the world's best-known functionalist architects, who pioneered the development of functionalism towards an organic style.

During the warm summer months, opportunities for swimming and beach sports abound, and some lakes even offer ice swimming during winter. Amateur ice skaters can practice their skills in Viitaniemi or on the lake Jyväsjärvi, which has a 3.5-kilometre long ice skating track. It is hardly surprising then that local sporting icons attain international success in swimming, skiing and ski-jumping. Sport is considered a national pastime here but even more so in this city, in Jyväskylä, the home of the country's only Faculty of Sport and Health Sciences and associated research institutes, much like the Australian Institute of Sport in Canberra. It turned out these were to play a pivotal role in the professionalization of ice hockey during Malste's playing days.

The ice hockey coaches studying at the Faculty copied training methods from other sports like athletics and stressed systematic physical training, including individual training programs and testing. The characteristics of players were monitored and compared, coaches were educated and developed, and their know-how improved. The first division teams in Malste's Liiga — 1975 to 1981 — were HPK Hameenlinna, Saipa Lappeenranta, KooKoo Kouvola, Oulu Karpat, Mikkelin Jukurit, SaPKo Savonlinna, Reipas Lahti, Vaasa Sport. The number of Finnish ice hockey player transfers from Finland spiked for the first time, and ice hockey became the nation's number one spectator sport in that relatively short period.

The Finnish game received more visibility in the media than ever before, and radio stations increased its local and regional fame, even though it took until the 1990s for the first significant television contracts. The international breakthrough of hockey here came at the end of the 1980s when the national team won the Olympic silver medal at the Calgary Winter Games. That was attributed mainly to the improved physical condition of players, the science of which had been developing here since Malste first played pro. The national team has since won the World Championship twice, in 1995 and 2011, and six Olympic medals. Finland is now considered a member of the so-called Big Six, the unofficial group of the six stronger men's ice hockey nations.

A short distance of ten houses from the lake house lived a family with two boys named Aki and Jack Valkonen. Friends of the Malste family, the boys moved to Adelaide in Australia, where Aki played two seasons with the Adelaide Tigers in the late-seventies. Then, one day, on a visit home to see his mother, Aki left a vacancy notice for a defenseman and a forward in the JyP office. So it was when Malste walked down the road to Aki's parents' place he was as good as skating in Adelaide and as prepared for hockey as he could be.

The brand new rink at Payneham, six kilometres north-east of the city's CBD, was hailed as the best in Australia when it opened in 1979. It gave the Adelaide Flyers competitive advantages over its interstate rivals, especially in attracting overseas players. When twenty-one-year-old Malste arrived in March 1981 with twenty-three-year-old forward Kari Pynnönen, it was home ice to the Adelaide Tigers, and Malste and Aki Valkonen paired in defense. The first three weeks were hard, but he and Pynnönen had played together in JyP for some time, and the Tigers were a very close team.

Malste quickly settled into the Australian lifestyle, even though he could speak little English. Although only imported for a short playing visit with the Adelaide Flyers in the new National Ice Hockey League, he found himself in the company of yet another countryman in Ari Pullinen; Canadians Orville Hildebrand, John Botterill and Wayne Kerry; and Czech, Vladimir Mihal. The other Adelaide defenders in contention in those first years were Bill Vis, Rodney Moylan, Steve Newbound, Peter Coutts and Rick Adams, who is still a close friend and visits from Canada, where he has set up a successful cheese factory.

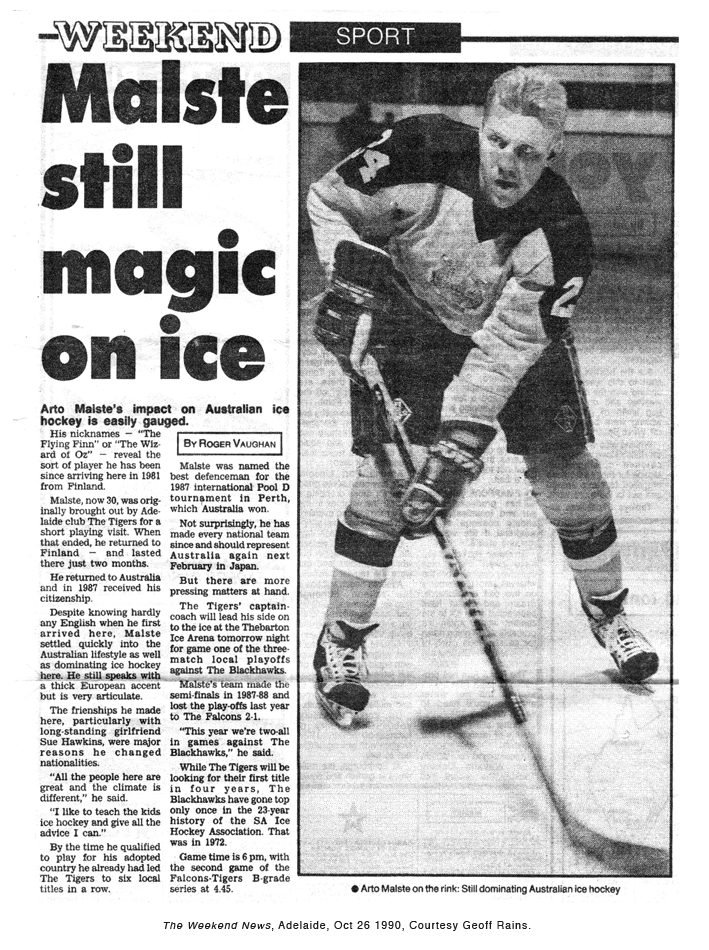

Friendships like these changed Malste's mind quite soon after the Tigers had fundraised his return airfare back home. He lasted just two months before returning to Australia, where he married his long-standing girlfriend, Sue Hawkins, and became an Australian citizen in 1987 at 27. He had already led the Tigers to six straight South Australian titles. He had learned enough to socialise and picked up more and more from work and newspapers. Flyers' teammate, Stephen Kilgariff, contributed "No worries, mate" to his early vocabulary, and Arte worked it hard, proving its usefulness in almost any situation. As player-coach of the Tigers for nine seasons, he had no worries with language barriers as a leader. His favourite coaching tip, "Don't worry about anyone else — concentrate your own game," worked almost as well every time, and the Tigers ended up with ten championships.

He kept some friends at home and stayed in touch with his family. Today, his talk is still heavily accented, very articulate, and forgiving of my cold-blooded butchering of his native Finnish, fourth as it is on the list of most difficult languages for English speakers. I will never know how Finnish fell behind Arabic, Basque and Cantonese. The Australian Passport Office never once spelt his birthplace right. It always began with a "D" — "Dyvaskyla", he pronounces with mocking contempt. It spread to other official paperwork and always raised eyebrows. I try but somehow find no sympathy. My hovercraft is full of eels.

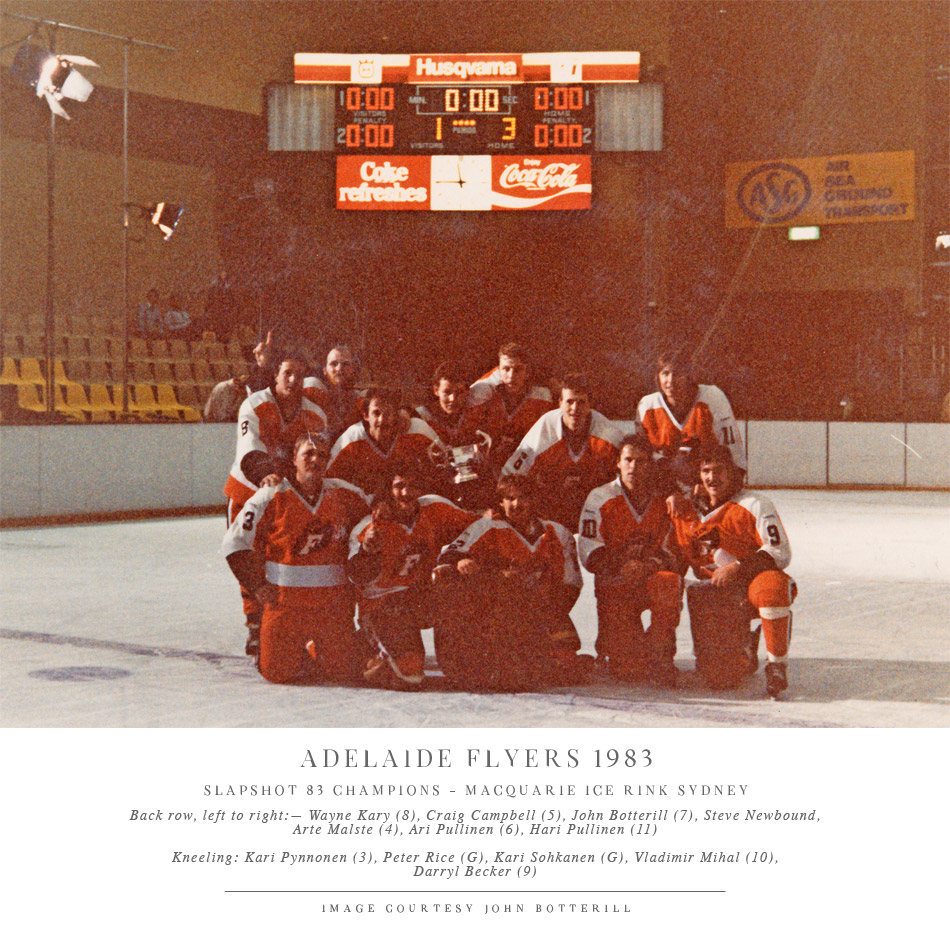

Malste is an understated man, and when he concedes his slap shot was "really good", I translate it more accurately to mean "devastating", the kind that goalies do not see, the hammer of the gods. It didn't come easy. It was more a skill acquired by patience and practice, by hitting five hundred pucks each week against an embankment back home in Vesanka. "You must practice. I practised all the time and scrimmaged in mid-summer". When the sport tested a new flashing puck for improved television visibility at the 1988 Nationals in Canberra, Malste happened to be on hand. John Botterill recalled the Finnish "boomer-shooter" slapping it into the net post, splitting it in two just ten minutes into the first game, its flashing lights erupting in a violent cataclysm of lightning bolts and pyrotechnics, or so I imagined.

Malste's wrist shot was also good, and he attributes his defensive success to good eyesight and skating. He could compute shooting angles like lightning and single out players in the best position to score in nanoseconds. His game was typically European, highly skilled and disciplined to avoid penalties, maximize ice time, and inflict maximal damage on opposition score lines, not opposition players, though punished just the same.

"Defenceman Arte Malste slides a crisp pass up to teammate Kari Pynnönen," wrote Flyer's regular goalie Mickey Sutherland in 1981. "From there, the husky forward sends a hard drive past the opposition goaltender — the result shows another "Flyer" goal". That happened many times that season, according to Sutherland, the six-foot Malste quarterbacking play, haunting opposition goaltenders. He had made his mark here after eight games and twelve points before crowds of about a thousand people each game. Already, he was possibly the best skater in Australia. He hit the ice with attitude — each shift had to score — he practised often and hard, and his instinctual will to win hardened with each new responsibility. In the minds of many back in those days, the officiating fell behind as the standard of play suddenly lifted, but the Flyers finished on top that season after winning the wooden spoon the previous year. Malste was a large part of it.

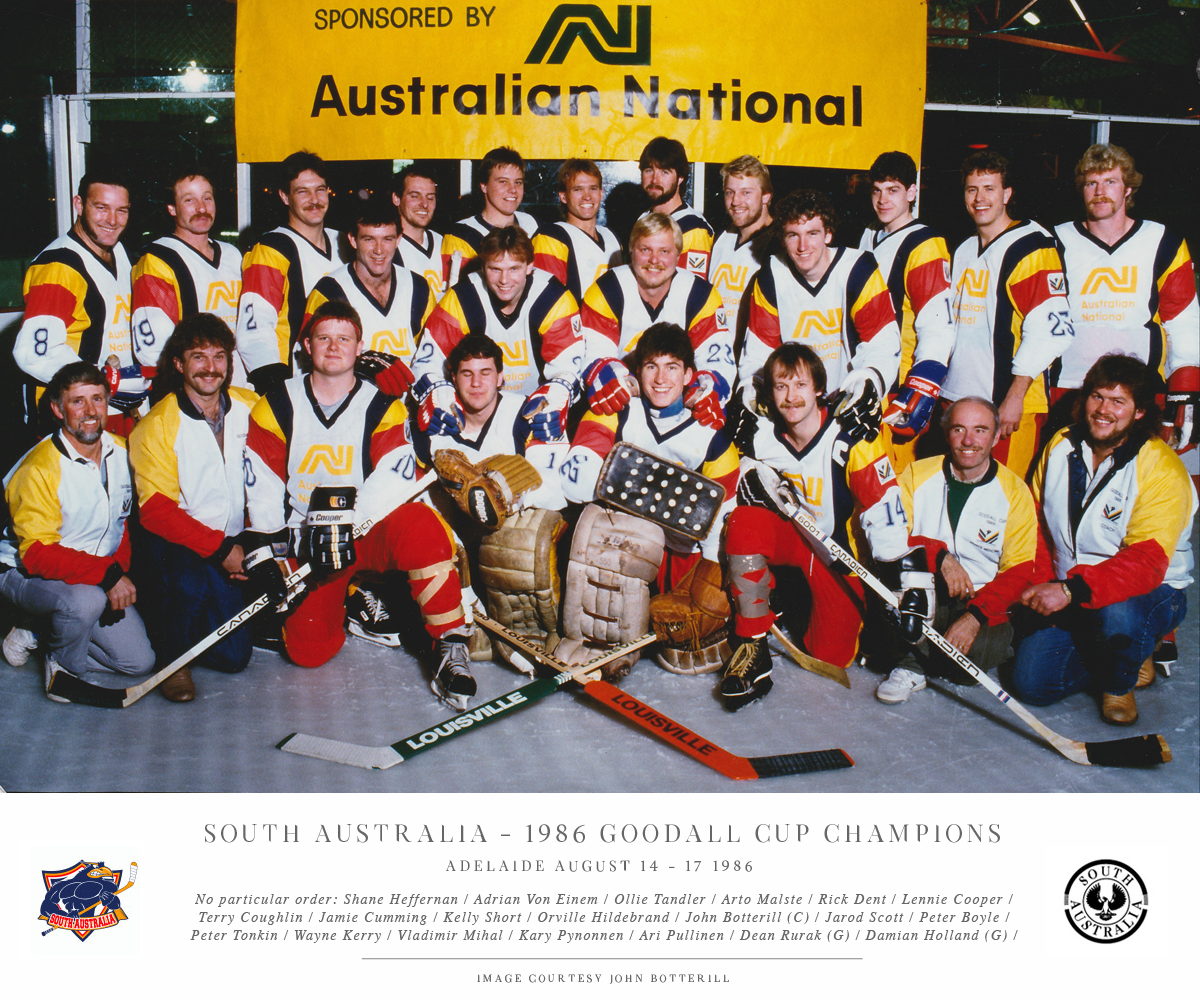

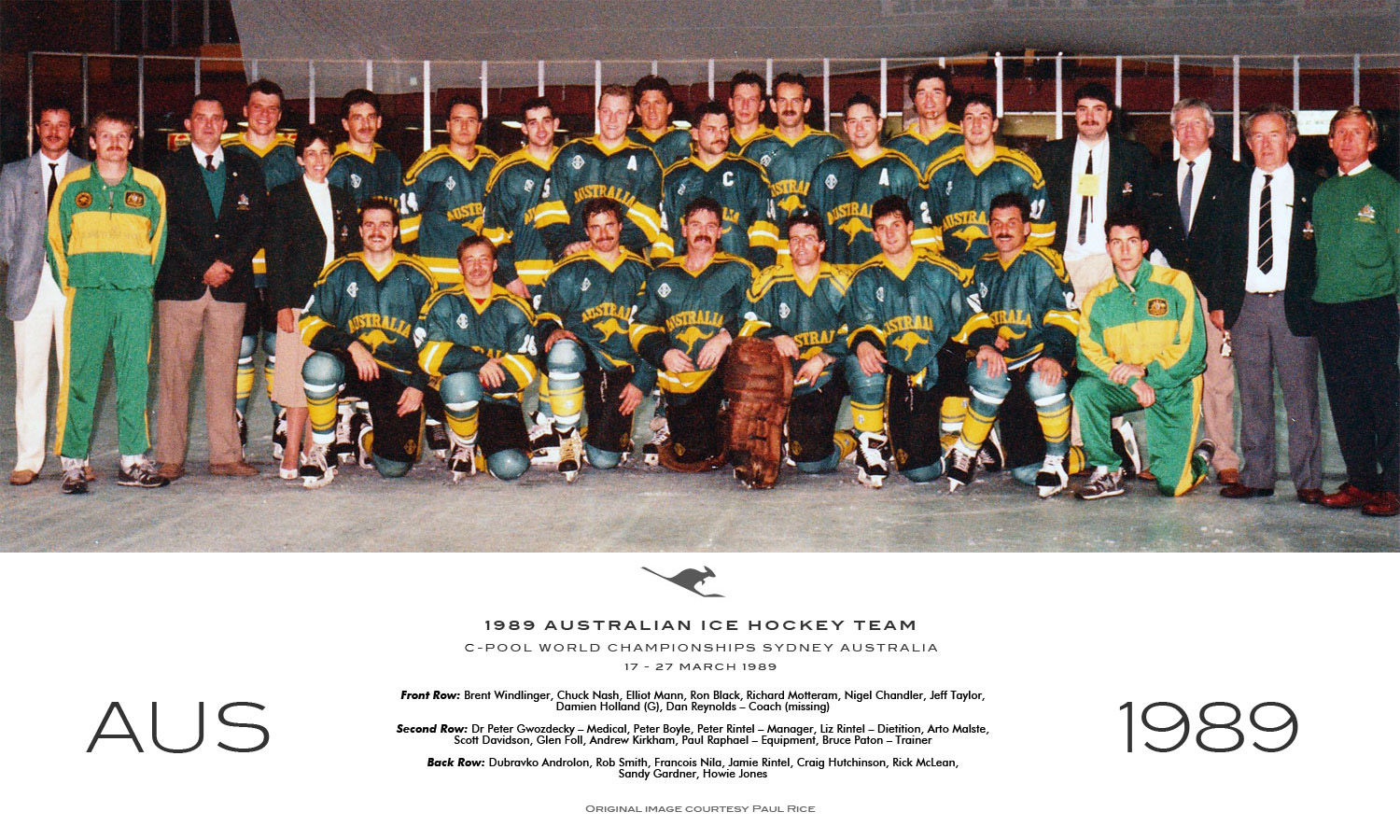

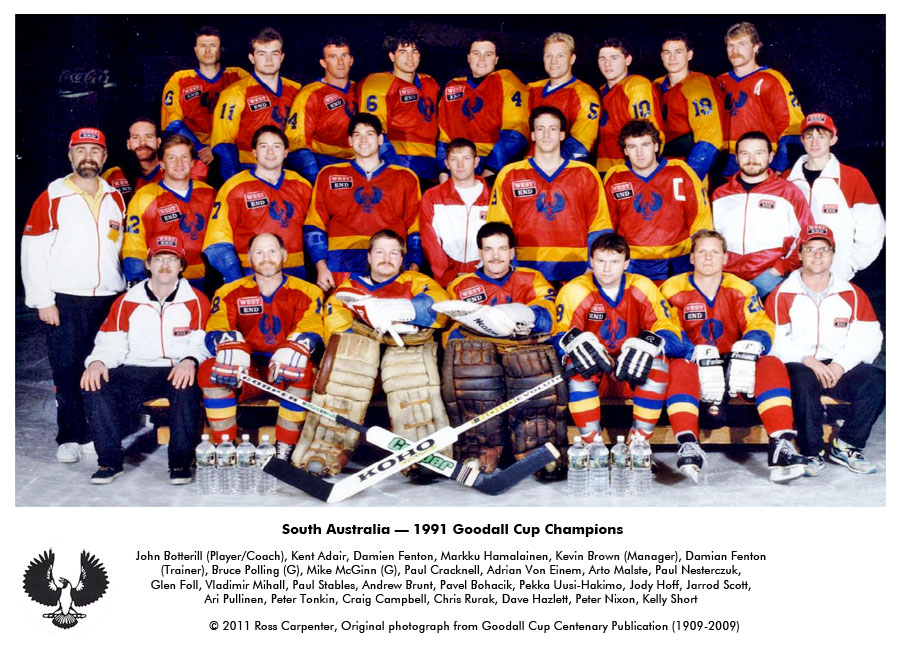

He represented South Australia for many years, winning the State's first four Goodall Cups, two pairs of back-to-back championships (1986, 1987, 1990, 1991), along with the Slapshot 83 championship won with the Adelaide Flyers. Then there were his ten premierships with the Tigers, where he was the leading scorer in 1984 while positioned in defense, and six-times Club Best and Fairest. In 1986, he was tournament MVP against the touring Carstairs Elks from Canada. In 1987, he made the Australian All-Stars. In 1989, he won the John Nicholas Trophy for the most valuable player of the Goodall Cup tournament and Best Defenseman, the second one of three (1986, 1989, 1994).

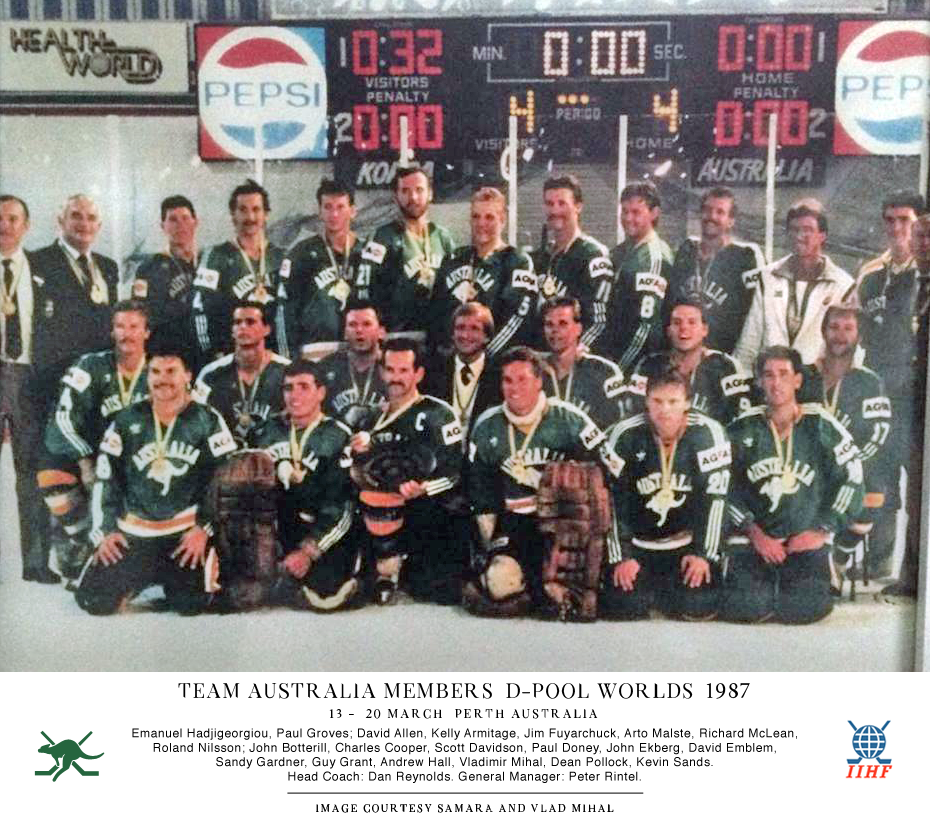

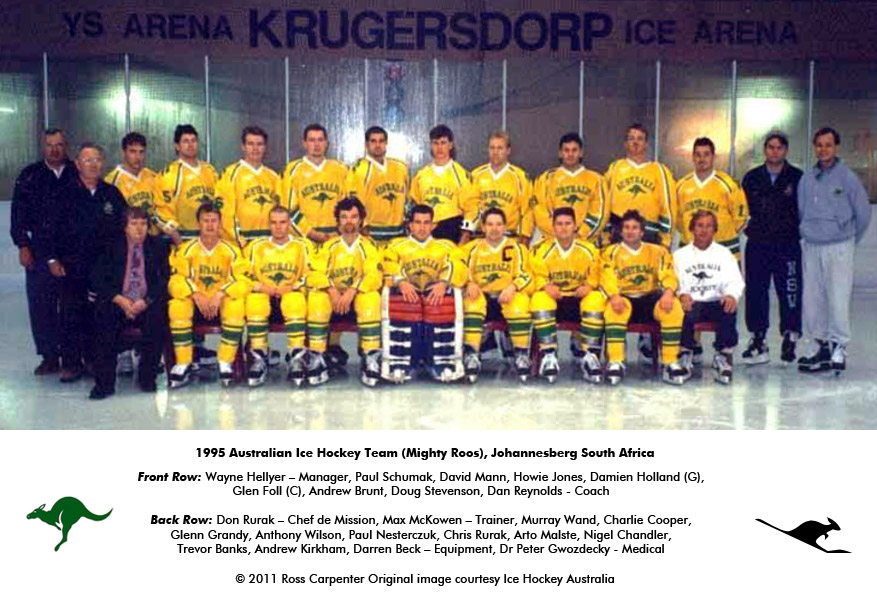

But the crowning glory was the "great honour" of winning for Australia the gold medal of the inaugural D-Pool Worlds at home in Perth in 1987, where he was also named Best Defenseman of the tournament. "Really good team," he says but does not dwell on it, nor on the other five times he represented his adopted country (1986 to 1990, 1995). He tallied an average of seven points a game in what was a veritable scoring festival in Perth, helping to set a new world record for the highest winning margin against an opponent.

In his first year here, Malste told us that Australian hockey will only develop if the organisers and people in charge concentrate on some of the younger players. From the mid-1980s to the early 1990s, he coached the Tigers because it was something he liked to do and to put it simply, the players here did not know, and he could show them. "I like to teach the kids ice hockey and give all the advice I can", he told the press in 1990, and only his demanding work as a carpenter stopped him eventually. Ask him what Australia can do to improve itself in international hockey, and he will tell you we could start training earlier. Yet, "we are what we are" — in need of the resources to build the rinks to seat the three- to five-thousand people required for financial viability.

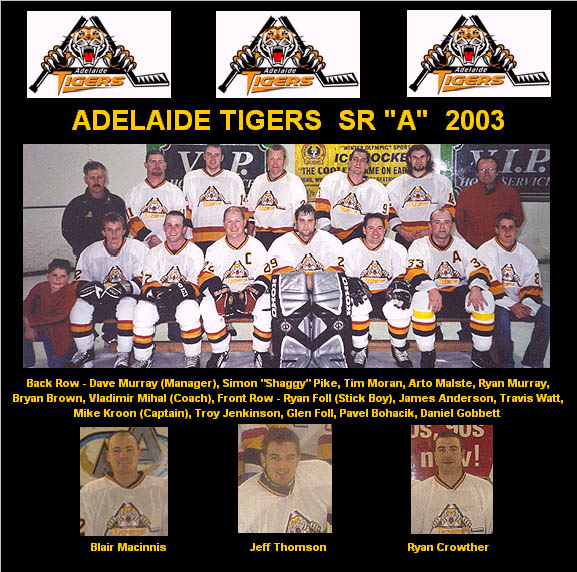

Malste retired from playing A-grade Tigers in 2003 when he was 43. "Do it one hundred per cent or retire. Don't keep doing it less than your best". For fourteen years, he had been Vladi Mihal's teammate. "Arte always led by example", says Mihal. "With him and Spooly Campbell in the line-up, I felt at the beginning of the game that we were already two up against the opposition". Now friends for life, they live in neighbouring suburbs and meet regularly. Malste continued hockey with the Adelaide Reds in the 35+ Division 1 of the Oldtimer's league, where he won the 2003 John Thomas Award, the Most Valuable Player in that division. A shoulder injury and corrective surgery ended ten years of that, and now he watches rugby, follows Port Power in the AFL, and hockey here, in Finland and the NHL. Contact sports are favoured.

His daughter, Yana, played netball as a young girl and is now a teacher in Melbourne's inner-city suburb of Fitzroy. Son Ben trained as an electrician, played football and the usual school sports, and now orders parts for a Melbourne company. "They have to find their way". His partner of five years, Lyn Harding, is a shop assistant and very supportive. Their respective children visit, but Arto and Lyn have a life together, a happily ever after.

In 1988, Malste's long-time friend, Aki Valkonen, fell off a scaffold and was left paralysed. He lived in a wheelchair for almost thirty years until his death in about 2010. At fifty-six, Malste still works as a carpenter on concrete formwork for multi-storey construction and admits his body is starting to feel it. He plans to stay active, to stay involved with his car clubs, and to travel. He does not want to stop, but when he does, it will be to rekindle an old love affair with vintage American cars, his red '59 Cadillac with the bullet tail lights and a lime-green '69 GTO Pontiac. He does not mention the thirty years of bone-crunching body checking. Instead, he matter-of-factly tells me his grandfather, who was married for seventy-two years and fought against the Russians in World War Two, died peacefully in his sleep in 2005 at an amazing age. His grandmother died the same way soon after. He remembers swaying on a swing one visit, listening to them talk. Neither had ever been in hospital. They had an understanding.

This shift in subject to longevity reminds me that Arte Malste's association with the Australian game has spanned over three decades, thirty years in which time he was exceptional at controlling the play in his defensive zone. Then my mind turns to Vlad Mihal, a little legendary in his own right, and I reflect on this assessment, knowing it to be incomplete. When, out of the blue, Mihal offered help to produce this story of his friend, he told me it was because "Arto is too modest to do it himself." But I know it was also because Arte Malste is special in Mihal's estimation and arguably the best to play in this country.

— Yana and Arte

— Yana and Arte

Notes and Bibliography

1. Structured interviews and biographical notes with Arte Malste, September 2016.

2. Nordic Elite Sport: same ambitions, different tracks, ed. Svein S. Anderson and Lars Tore Ranglan, 2012. "Lions on the Ice: the success of Finnish hockey", Jari Lämsä.

3. The Weekend News, Adelaide, October 26 1990, "Malste still magic on ice" by Roger Vaughan

4. Correspondence from Vlad Mihal, July - September, 2016

5. Allsport News, 1981, "Payneham Flyers No. 1 in Australia" by Mickey Sutherland

6. Adelaide Flyers Profile for Arte Malste, July, 1981.