The Story of the Goodall Cup — Part 1

Symbol of Australian ice hockey supremacy

![]() Anything or anybody who can survive 100-odd years of neglect, kicking around, misuse and just plain lack of respect, deserves to become a little legendary. And that is what this old "mug" looking unusually spick and span has become — a Legend of Australian ice hockey. Its sheer genius for survival has made it one of the oldest trophies still contested in Australia

the third oldest national ice hockey trophy in the world — and with the care and respect it now gets in the Hockey Hall of Fame in Toronto, it will outlast a lot of the men who give a lot of energy and break a lot of heads to become part owners for a year. Not that earlier generations of players were any less affectionate towards "The Pot", but their approach was perhaps more light-hearted and their escapades often too rugged for its somewhat delicate constitution.

Anything or anybody who can survive 100-odd years of neglect, kicking around, misuse and just plain lack of respect, deserves to become a little legendary. And that is what this old "mug" looking unusually spick and span has become — a Legend of Australian ice hockey. Its sheer genius for survival has made it one of the oldest trophies still contested in Australia

the third oldest national ice hockey trophy in the world — and with the care and respect it now gets in the Hockey Hall of Fame in Toronto, it will outlast a lot of the men who give a lot of energy and break a lot of heads to become part owners for a year. Not that earlier generations of players were any less affectionate towards "The Pot", but their approach was perhaps more light-hearted and their escapades often too rugged for its somewhat delicate constitution.

Mind you, the Goodall Cup never was an object d'art. Even in its virgin glory early last century, it would never have stirred more than a slight curling of the upper lip from any self-respecting member of the Goldsmith's Guild. And you will no doubt prefer to pass over the extraordinarily varied service into which it was pressed during the first century of road trips, if you have ever slurped champagne from it. But whatever else it lacked, it was durable, and this was surely the quality that eventually won the respect of its carefree handlers. The honourable scars this veteran wears suggest it is anything but the symbol of Australian ice hockey supremacy. But the history of Goodall Cup hockey is the history of hockey in Australia, and the names that appear on the trophy really have made the game's history.

— Ice Hockey Guide, [Abridged and corrected] Newsletter of the Victorian Ice Hockey Association, Melbourne, July 30 1966 [4]

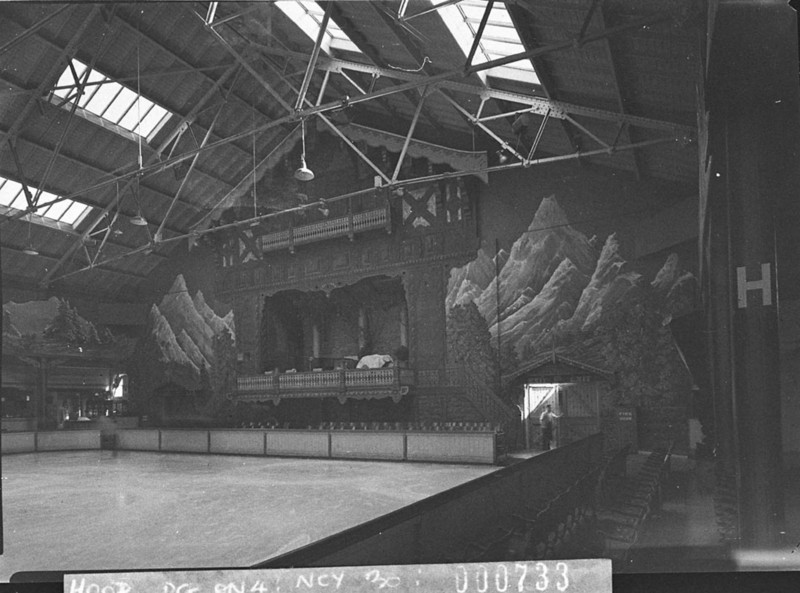

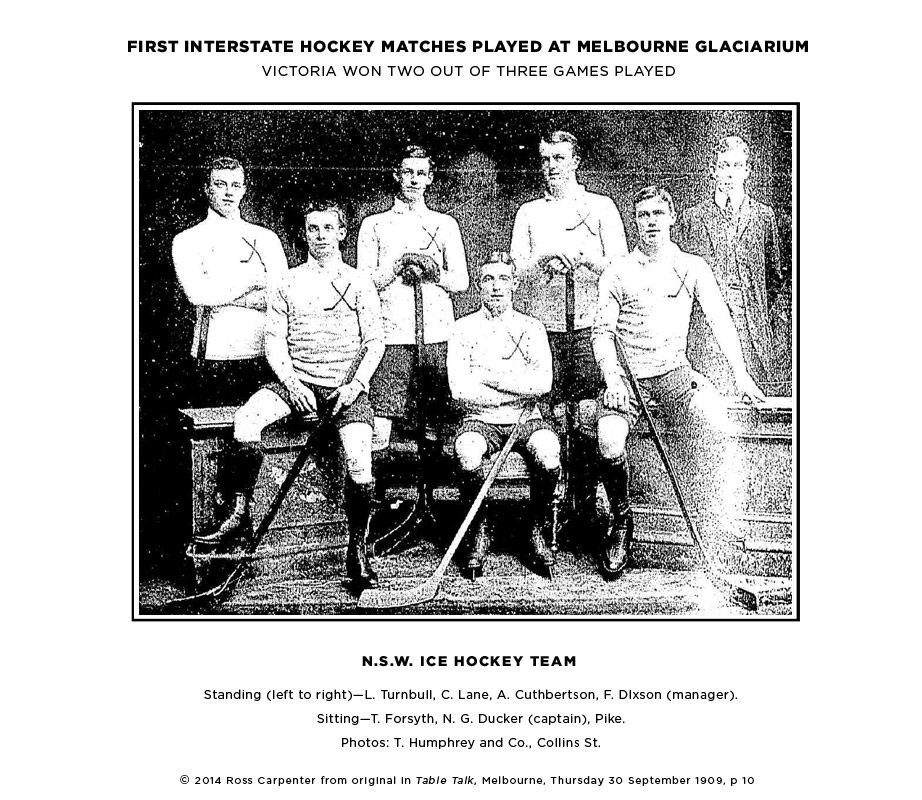

IN 1904, THERE APPEARED on the board at the old Glaciarium Ice Palace in Hindley St Adelaide, a notice convening a meeting of any skaters interested in the introduction of a new form of amusement on the ice. The meeting was duly held, and it was explained to the assembly the idea was to play a game on the rink akin to roller polo. The rules to be adopted were based on that game and the implements used were to be the same. The idea met with general approval, and thus the game of "Hockey on the Ice", as it was then called, was launched on a tiny oval-shaped skating circuit with a post in the middle to hold up the roof. At the meeting was H Newman Reid, developer of the experimental Adelaide rink, and also the Melbourne rink a few years later in 1906, the birthplace of Ice Hockey in Australia. Two of his sons, Andy and Hal, were also present and all three were destined to have great influence on the fortunes of the game.

In the beginning, the Victorian skaters in Melbourne were not sufficiently advanced or adept to contemplate anything more than a dignified amble round the rink. A group of younger skaters, spurred on by the Reid boys, played occasional games of hockey and challenged sailors from the visiting American warship USS Baltimore to a game. The night of the match saw the rink crammed to the rafters, and though the Melbourne team was defeated after a splendid match, such a spark of enthusiasm was kindled that preparations were made for the formation of the Glaciarium Ice Hockey Club to commence in 1907. It was the very first in Australia and a rink also opened that year in Sydney, New South Wales, setting the stage for very fast things to come.

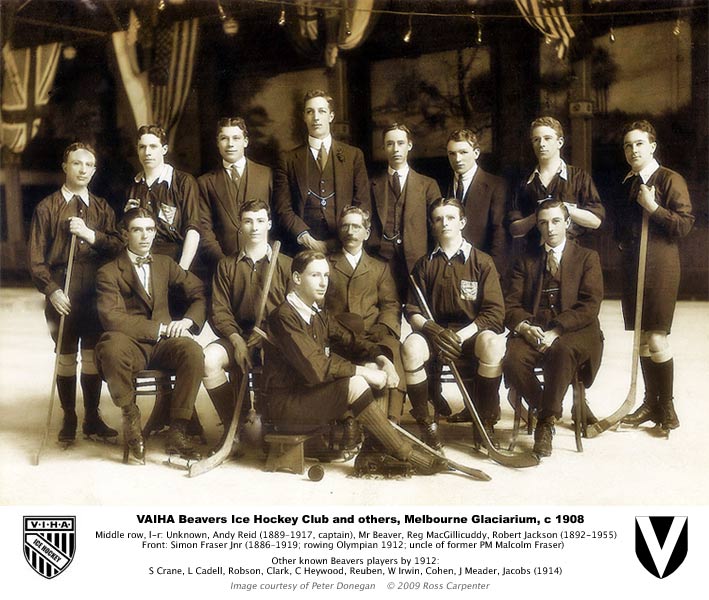

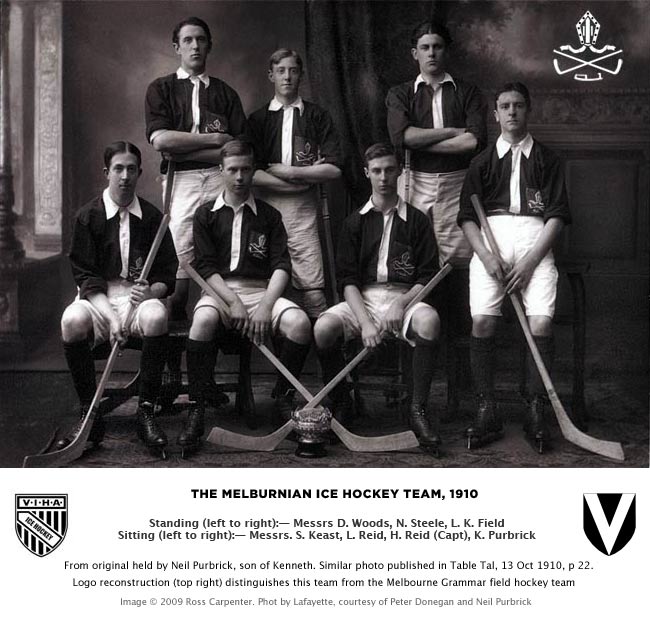

In August 1907, the Victorians discarded the bandy ball for a puck in two games of hockey against the touring Canadian lacrosse team played before a large and fashionable audience. The next season, quite a few matches were played, the touring American fleet sent teams ashore, and the visiting Canadian cadets played games. The first women's ice hockey was also played and the International Ice Hockey Federation was founded. Between the closing of the rink in 1908 and its re-opening in 1909, the Victorian Ice Hockey Association was formed with Andy Reid among its founding members, and four ice hockey teams — Glaciarium, Beavers, Brighton and Melburnian. These were the first ice hockey teams in Australia and the first association.

By then, the game was played with imported Mic Mac sticks under Canadian rules. There was no offside and though there were penalties of free hits for using one's stick at shoulder height in the manner of a scythe, or for placing a stick between an opponent's legs, the umpires required to see some form of garrotting before the play was stopped. Pushing in the back and tripping were looked on as too trivial to worry about. In those days, some players were almost unapproachable, so adept had they become at ramming the butt of their sticks into their rival's stomachs. So, it became a necessary part of a player's training to become expert in the art of secretly inflicting great physical anguish on an opponent.

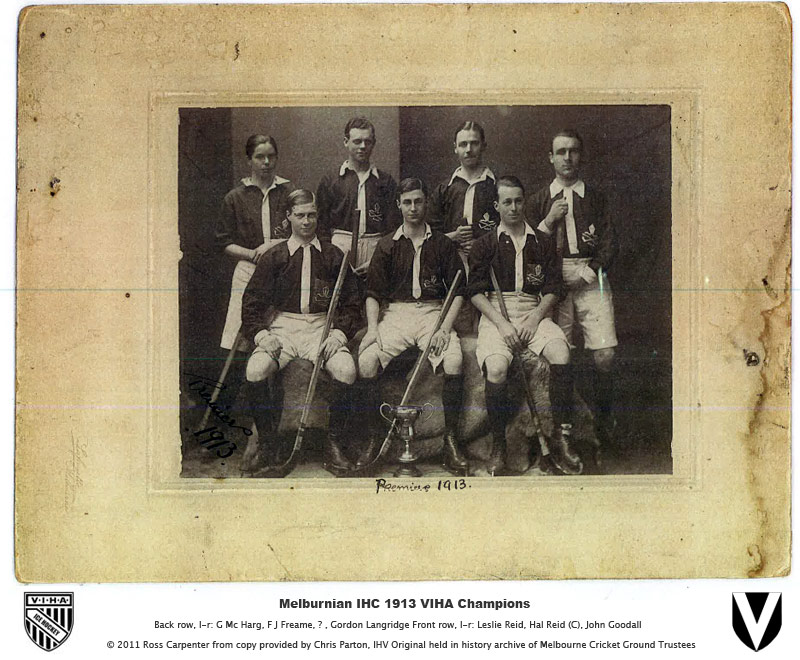

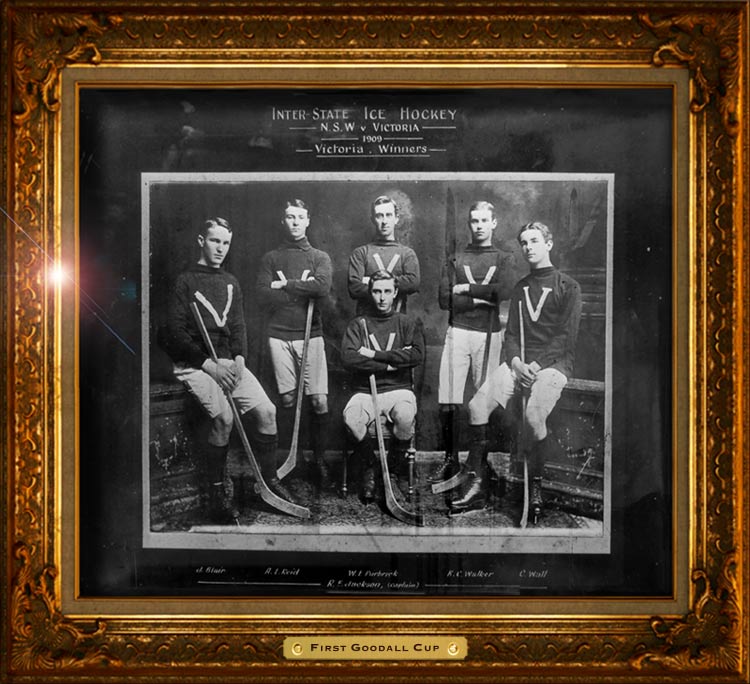

At the end of that season, the year after Canada introduced the Allan Cup, New South Wales sent its first team to Victoria. It was fast but inexperienced, and the Victorians captained by Bobby Jackson were the first winners of the newly presented interstate trophy. It came to be known as the Goodall Cup after its donor, the Melburnian player, John Goodall. Jack himself was a pretty fair hockey player, rated one of the best cover points in the game. In those days the team lined up with three forwards and a man directly behind the centre man, and then a man behind him again. That was cover point.

In 1910, the Melburnian team was again unbeaten and the first Victorian team visited Sydney, captained this time by Keith Curwen Walker. Again they won. In 1911, the Victorians instituted some new rules and acquired five-dozen Spalding championship sticks, bringing hockey up to a pretty high standard. Melburnian shutout the Beavers with a record 29 goals in the final game, and the first club competition commenced in New South Wales with three teams — Corinthians, Wanderers and Ottawas.

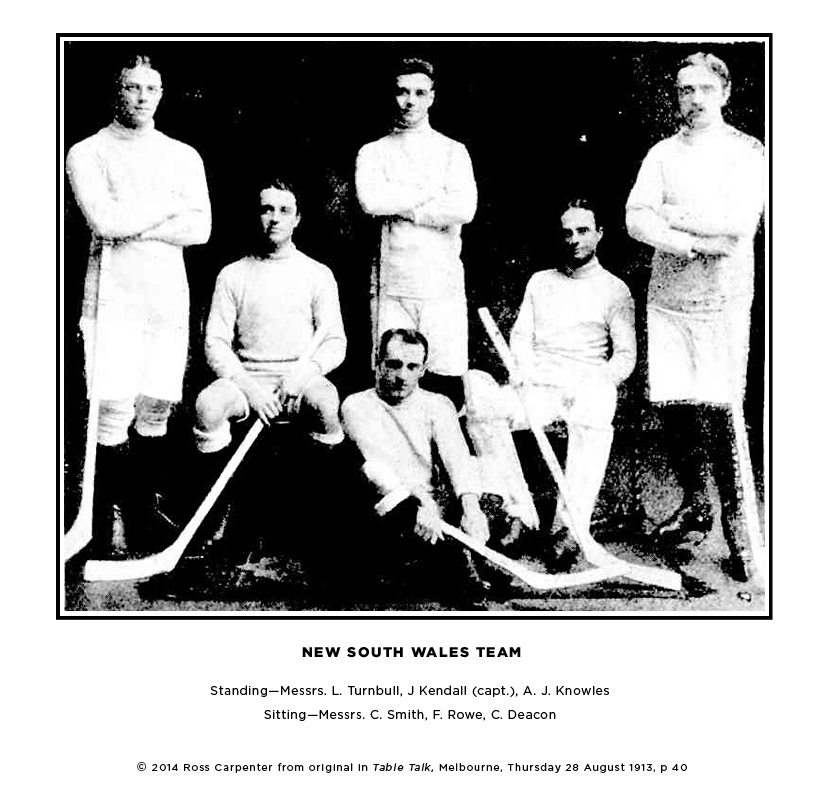

When New South Wales arrived for the 1911 Cup, it was evident from the first game that their play had greatly improved. The reason was the Canadian university player, Jim Kendall, the captain of Corinthians. His amazing speed, accuracy and tremendously hard shot had not been seen in the game before, and it caused frightful consternation amongst the Victorian selectors and team. The puck handling of the New South Welshmen was now excellent and their system well developed. Though the average standard of the Victorians was as high as the rest of Kendall's team, his presence put them a long way ahead, and he alone was almost a match for the Vics. Yet, there was no selfishness in his play.

Before the second game, there was much discussion as to the methods required to check Kendall, and it was finally decided to give two players a roving commission to follow him through the match. This made not the slightest impression on him, and again Victoria was badly defeated, thus losing the Cup for the first time.

In 1912, 6-men a side was played, not seven, offside was introduced, well ahead of almost everywhere else in the world, and fans witnessed the last of the blood-lust games. Seven of 14 players were seriously injured in the final match between Melburnian and Ottawas. So violent was it, a meeting was called directly after to tighten up the rules of play. Victoria visited Sydney again this year and suffered defeat by two matches to one.

In Melbourne in 1913, much to the visitors' surprise, the home team won the first and second matches and regained the trophy. In the middle of the 1914 competition came war and hockey was abandoned in both cities.

Between the Wars, 1919 - 1939

The Sydney rink was closed through the war years and opened again in 1920. The Victorian association was reformed and most of the movers were newcomers. An enormous amount of rebuilding had to be done. The old records, rules and equipment had been lost, and nearly all the pre-war players had disappeared or been lost in action. However, arrangements were made for some matches and preparations made for next year's competitions.

In 1921, things were still rather chaotic, but the cups had been found and teams were formed. When it was suggested a team should go to Sydney to resume the interstate series, Victoria proceeded to look around for men. Few of the old players were alive or capable, but finally a list was got together. Hal Reid did not return to the game, Andy Reid was killed in action and Lesley Reid had moved to Sydney with his family where he became the driving force in rebuilding the game in cooperation with John Goodall in Melbourne.

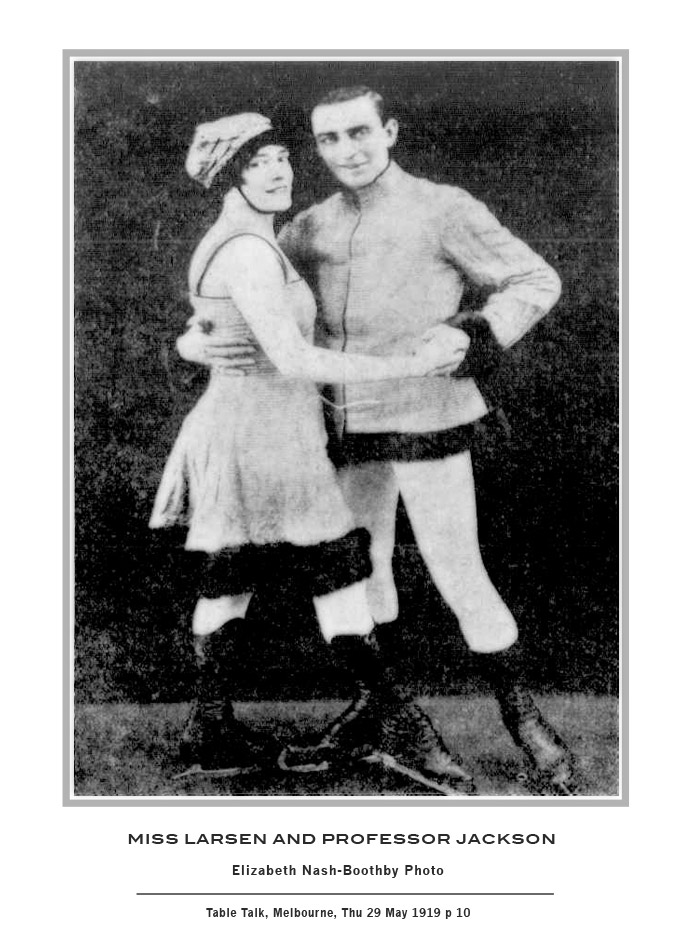

Goodall's first interstate game on record was with the second Victorian State team in 1910, when he was 17-years-old. In 1914, he became the fourth NISAA National Men’s Skating Champion following Hal and Andy Reid. In 1916, when he was 23 years-old, he inherited a share of his grandfather's estate, a purchasing power in excess of $20 million in today's money, and much more taking account of all assets. He was already at that young age a prominent, independently wealthy, stock and share broker who worked with the Queen St company his grandfather had established. He became president of the VIHA and was captain of Victoria in 1922, the last occasion the state was to win a Goodall Cup for a quarter-century.

New South Wales Ladies' Ice Hockey Team, Sydney Glaciarium, Australia, 1926. Footage courtesy John Maclurcan, grandson of Charles Maclurcan (1889-1957), one of the earliest Australian skating champions, skating gold medallists (Davos), and presidents of the New South Wales Ice Skating Association. Player ID at 1:38 — Back row, left to right: Elsie Rae (centre) C White (referee), Annie Baker Ford (captain and keeper) Ettie Wallach (right wing). Front row, left to right: Ita Waite (point] M McWilliam (coverpoint] Nancy Kerr (left wing).

Following the deaths of 60,000 Australians in the war, the Gower Cup dropped into ice sports like a bookend for the next decades. It was the missing pair of the Goodall trophy, and its arrival coincided, both symbolically and literally, with new life for post-war ice sports. In that one brief moment, organised National women's ice hockey was born in Australia and, soon after, a brand new generation of National men's ice hockey, and the first organised junior ice hockey and racing league in Australia. Throughout this decade, Victoria was beleaguered by one rink problem after another, but each was neatly solved, and these appear to have still been the halcyon years for ice sports there, as well as in New South Wales.

These events were closely related to developments occurring in North American amateur ice hockey. Sir H Montagu Allan CVO, son of Sir Hugh Allan, had donated the Allan Cup in 1908, the year before the Goodall Cup Interstate series first commenced. His first cousin, Lady Isobel Brenda Meredith (Allan), donated the Lady Meredith Cup in 1920, two years before the Gower Cup. This was the first ice hockey trophy to be competed for amongst women in Canada, and Lady Meredith was the wife of Allan's friend, Sir Vincent Meredith, of Montreal, a son of John Cooke Meredith.

Victoria's 1921 Goodall Cup squad was not the best the state had iced, but it was probably the most enthusiastic, and notable for the entry into interstate hockey of Ted Molony. He was captain of one of the two most successful Victorian ice hockey clubs of all time; captain of Victoria nine times; a veteran of fourteen Goodall Cups, champion of some, winner of one (plus a tie); a State speed skating champion; a National skating champion; operator of six ice rinks; and an ice sports builder for over half a century in four States.

Both States agreed the Goodall Cup would be contested over two twenty-minute periods, either side of a ten-minute interval, with a 6-player, single-shift, team structure. There were no line changes, nor substitutes; the same six players contested all of both 20-minute periods. Some playing rules were still negotiated by State captains before the games (Kendall, Reid, Molony and Goodall), and the "relay system", two substitute players, was not introduced in Melbourne until the first test of the 1926 Interstate series, on August 9th.

Even then, the "relays" replaced players for a whole period, unlike the regular line change that occur every few minutes in the modern game. By 1930, change-over of the two substitutes occurred more often, evolving to include more "relays", whole lines, and then two and three lines, until the regular line change of three shifts of five skaters emerged soon after the War, at least in Victoria — hockey as it is played today.

In 1922, the Victorian association got firmly on its feet and the first association was formed in Sydney with four new teams. Victoria astonished the NSW team by winning back the Cup, but it was also the start of the first of the long unbroken victory runs by NSW. Goodall guided the rebuilding of the decimated Victorian game; captained the last of the Victorian Goodall Cup champions for a quarter-century to come, paved the way for the first interstate women's ice hockey competition that year; and became the first president of the first national association in 1923, the year a fifth team named Glebe Lions was formed in Sydney.

He married Kathleen, who presented the first Gower Cup in 1922, retired as a player, returning briefly only for Kendall's farewell series in 1925, busied himself with setting the sport on a national footing, and dutifully presented the Goodall Cup at interstate tournaments.

From 1924 to 1932 ice hockey did not change to any great degree, nor did the rules materially alter, yet the game had improved out of sight. It was more open, more scientific, faster, and very much less brutal. The equipment was far superior and the players as a whole were somewhat better, but not individually. The referees were definitely less bloodthirsty.

However, one writer lamented two things were lacking which in the past made the game such a success. First and foremost, the intense enthusiasm shown by every player for hockey as hockey, and their equally earnest desire to become not only proficient as puck handlers, goal scorers or defencemen, but to be able to think, and read what was required in each department of the game. "Ice hockey is the best and fastest game played by man on his own legs", he wrote. "But it is a hard master and it requires the use of his brains as well".

Goodall returned in 1930 after a five-year absence to head the Victorian association, following the death of its president. In the depths of the Great Depression, he presided over the re-organisation of the VIHA clubs with the aim of giving "young players a better chance to improve themselves". In the 1931 season, St Kilda IHC was dropped, and the three remaining clubs — Hawthorn, Brighton and Essendon — were restructured with both senior and junior teams. Seniors played Monday nights, and juniors on Thursdays. The first inter-club juniors and the first inter-schools competition were both created that year, the first true, age-delimited junior ice hockey leagues in Australia.

While Leslie Reid, one of the sports' prime movers, died at a tragically young age in Sydney, some of Kendall's young proteges took to the ice. Among them were Jim Brown, Australia's first international ice hockey player and speed champion, and Ken Kennedy, Australia's first winter Olympian. Both played pro hockey in England and their return placed the game on a different footing. Brown's club, St George, even changed their colours to the grey, red and white of Britain's Grosvenor House Canadians. In 1937, the fifteenth year of New South Wales' ruthless custody of the Cup, when the Vics never got any closer than usual to earning the right to take it home, Victoria's Napthine twins took care of it.

One of the outstanding events of the Cup series in those days was the official dinner at which speeches, presentation of trophies and other courtesies were merely a prelude to the big moment when the Cup brimming with champagne went the rounds. Cliff was a veteran of the 1932 Cup custody controversy. His brother, Mil, also made the 1937 State side, and both went missing after the presentation. To the great delight of their teammates, the twins produced the Goodall Cup from their luggage, when the train was well out of Sydney and on its way home to Melbourne. The hijacked trophy was duly installed with honour for months in Ted Molony's skate shop window in King Street before it was even missed in Sydney. Everyone thought someone else had taken it home on the fateful night.

But in the end, New South Wales "held the Cup" for twenty-two years between 1923 and 1946, their winning streak only broken by a series tie in 1932. They had secured nine straight championships, between 1923-31; then the tie; then a further seven, 1933-9. In that time, Victoria's lack of success on the ice did not stop them from gaining possession of the Cup by other means, and the number of times it was lost after official functions, only to turn up during the train trip back from Sydney, did not seem so funny to the NSW visitors.

By the late 1930s, Jim Brown found himself publicly condemning criticism of the standard of British and Australian ice hockey by a professional player from Canada. "Australian ice hockey can't be compared with the professional leagues in Canada and America", he said "for they have the pick of the best players in the world. But Australia ranks very high in world company in amateur ice hockey. In fact, only 4 or 5 countries would be likely to beat Australia, even as she is at present with no international experience. Canada, USA, Great Britain and Germany would probably be too strong for Australia, but countries such as Sweden, Norway, Poland, France, etc are not above the Australian standards".

Percy Wendt won 9 Goodall Cups representing New South Wales in most clashes with Victoria in the two decades between 1931 and 1951. He was a true 2-way forward who played left wing, but who also looked great at centre-ice or in defence. Those who had seen him play thought he was more successful in defence than offense, and that was saying something. Because the 23 goals he scored in Goodall Cup hockey between the wars, was second only to Jack Pike on 29. Kendall and Leslie Reid had fed Pike, two of the all-time best quarterbacks in the local game. Wendt surpassed Pike's record during the interstate games he played after the war, to become the most successful goal scorer in the first half-century of the Goodall Cup.

Just before the onset of the second world war, Melbourne and Sydney each received their second rinks; Jimmy Bendrodt's Ice Skating Palais at the Sydney Showgrounds and H H Kleiner's, St Moritz on The Esplanade at St Kilda. They were no angels these two, but they were the first to commercialize ice sports in Australia. As with many successful entrepreneurs, important people backed their ventures. Each had done more for Australian ice sports than anyone since the founder, H Newman Reid.

A professional team named the Bears was also formed at Bendrodt's Ice Palais in 1938 in the colours of Canada. They won 10 of their 11 games and tied the other. Each game was sold out. The long-awaited St George versus Bears game was played hard with furious body-checking and a very high skill level.

In those days, in that league, only defending players were allowed to body check in their defensive zone, and only against an attacker in possession of the puck, never in the back, not gathering momentum, not within 5-feet of the boards, and not with the knee or elbow or stick pushed out in front. The Bears held St George scoreless to win, 1-0, Robertson netting the match-winning goal assisted by Fielder. The crowd repeatedly hooted St George, which included NHL one-gamer, Tom Coulter, and counted them out each time they broke the checking rules.

Robertson fell behind the St George goal in the first half and struck his head heavily against the boards. He recovered after a few minutes but fell again, this time striking the back of his head on the ice. He was carried off but returned at the start of the second half, only to be knocked out for a third time, recover again, and score the game-winning goal.

Several St George players were sent off in the second half and there were as many as eight players prostrate on the ice in a melee at the one time. The sport's regular journalist said it was a shame to see the way the Bears star was targeted and "continually bashed to the ice surface by illegal play". Bendrodt took exception to the way the game was refereed and showed players how to depart the NSW association and form their own.

The dispute left top players like Percy Wendt, Widdy Johnson and Bede Moller out of the state side, out of the sport for a season, and probably also the war years. It even spread to Victoria where it affected players such as Victoria's captain, Ellis Kelly, son of W L Kelly, manager of the Australian Test Cricket team during the Bodyline series. The local association threatened all that it could, including punitive measures through its affiliation with the Australian Olympic Federation. Then it announced player suspensions from 2 to 5 years duration.

Bendodt's Canadian Bears vs Sydney Monarchs, Ice Palais, Moore Park, Sydney, 1938. The standard of the Australian game and its equipment in 1938 when imported players were introduced for the first time. The Bears in the light uniforms defeated Monarchs, 11-0. Source: British Path, soundtrack missing.

Among other games, the Bears went on to beat the New South Wales All-stars, 9-4, on October 5th, and the Australian national team, 5-4 and 8-3 later that month. When the dust had settled, the officials said in a reversal of form "the visit greatly assisted in raising the standard of the game in Sydney. Their tactical work and positional play have been something new to Australian players who have not had the opportunity of witnessing games played overseas, and much has been learned of methods not previously exploited." Many of Bendrodt's match reforms, such as two referees, were later implemented.

In 1939, the last Cup before the war interruption, the Victorians had forced their arch-rivals to a draw in the first two tests — 2-2, 2-2 — and their manager Ted Molony delivered the national association an ultimatum. Victoria would not play the decider with referee Jack Paton. Molony, an accredited referee and a driving force behind the national game, accused Paton of not enforcing the rules and allowing the second test to be reduced to angry outbursts, charging, frequent falls and fights. He didn't say publicly Victoria could have won had it been refereed properly.

Unfortunately for Victoria, their captain Hughie Lloyd and Cliff Napthine had returned home for "business reasons" and on the night of the decider they played instead for their local clubs. Lloyd's replacement, Johhny Whyte, was prevented from flying by bad weather and the Victorians lost the decider and the 1939 Cup, 1-2.

Jim McLauchlain, Scotty Fraser, and Bede Moller were other standout players for New South Wales and Victoria had George Hewitt, Spot Lloyd, Cyril Macgillicuddy and Bertie White. These men played a big part in keeping the game alive when it seemed likely to fade away.

Inter-rink hockey matches between the Glaciarium and Ice Palais were a feature of the 1939 and 1940 seasons and something similar happened in Melbourne. St Moritz became the flagship for Victorian ice sports and the focus of Australian ice hockey shifted there for many decades. The state achieved an enduring ascendancy for the first time since the Australian game had been founded there in the early 1900s.

Notes and bibliography

[1] Legends articles and referenced sources

[2] Glaciettes, Newsletter of the Victorian Ice Hockey Association and the National Ice Skating Association, Melbourne, Vol 9 No 6 July 30 1932

[3] Beryl Black Archive

[4] Ice Hockey Guide, Newsletter of the Victorian Ice Hockey Association, Melbourne, July 30 1966

Special thanks to Jason Sangwin for use of the photograph of the original Goodall Cup from the Hockey Hall of Fame, Toronto.

Melbourne Glaciarium, Interior around the time it opened, City Road, Southbank, Melbourne, c1906 [3]

Melbourne Glaciarium, Cradle of a national sport, City Road, Southbank, Melbourne, c1939 [3]