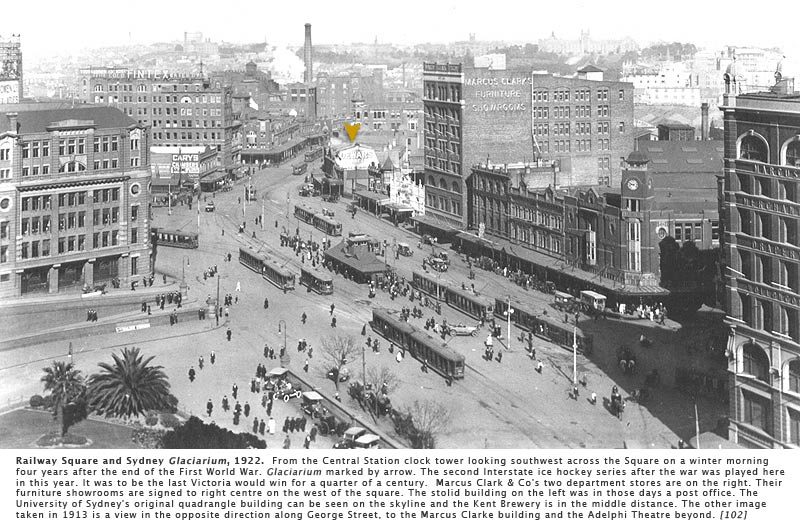

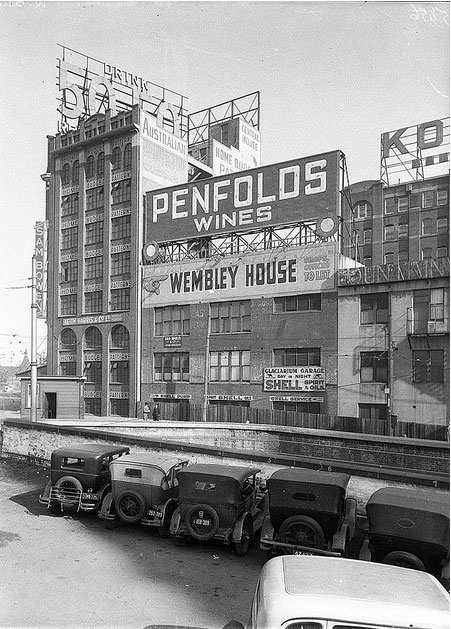

Rear George Street, Haymarket

Looking SW from Bijou Lane showing site prep for extensions to Marcus Clarke Building, 1926. On the left is the Marcus Clarke building and the middle is the Wembley House (839-841 George St), built over the Darling Harbour Goods Line during 1925-26. Courtesy Chris Hampton.

Skaters of Sydney

Sydney Glaciarium (1907 – 1955)

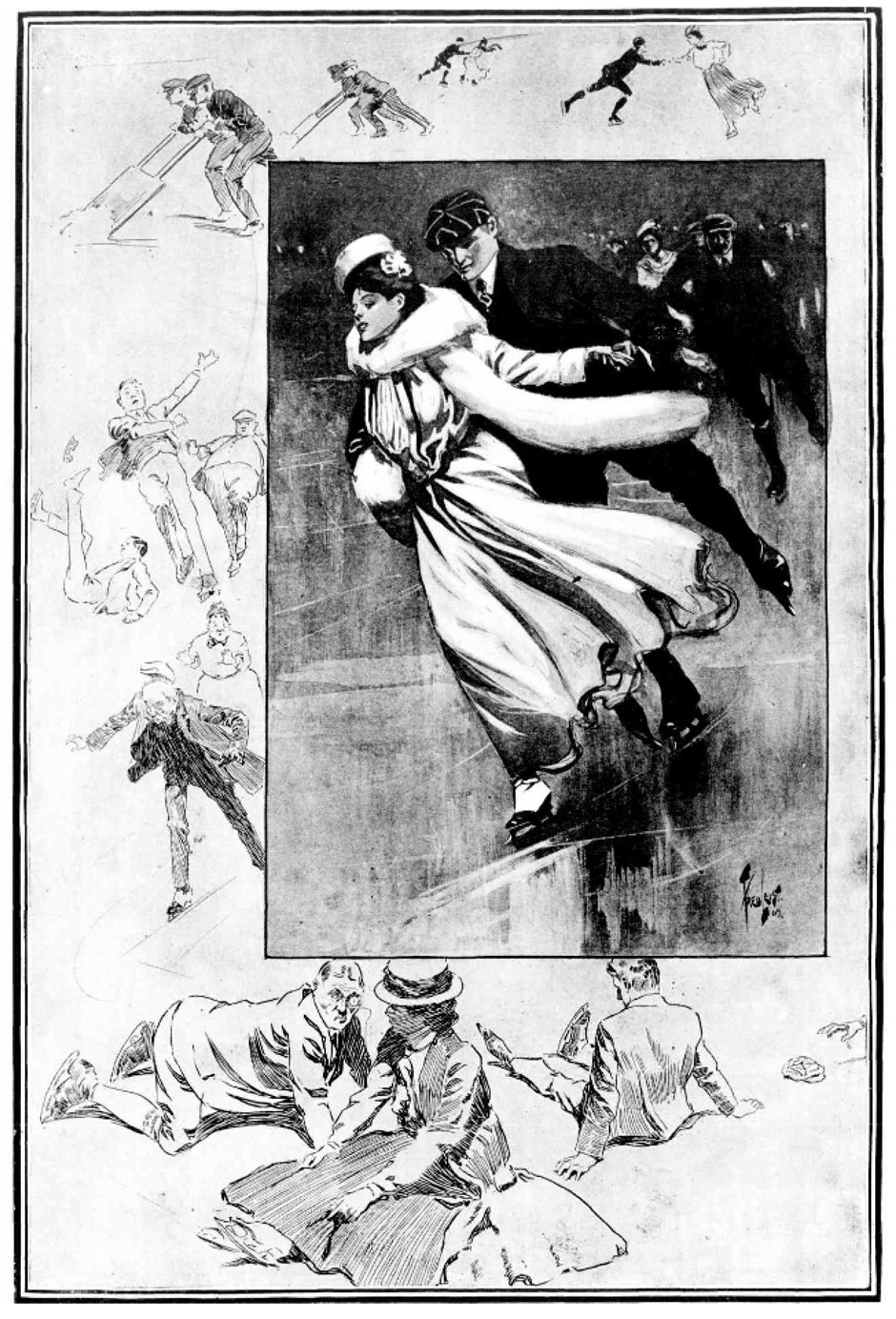

![]() Skating on the ice in Sydney! How strange it sounds! There are many readers of the "Sydney Mail" in whose minds a train of happy memories will be called up by the scene which our artist has here portrayed. Memories of glorious outings on lake or stream in the old land, when the heart was young, and there was thought of nothing but the enjoyment of the moment as, in the crisp, wintry atmosphere, they raced along the glassy surface of the ice. No exercise is more exhilarating than this. In our sunny land, Jack Frost wields but little power, and open-air skating is practically unknown. Through the enterprise of the Glaciarium Company, however, the people of Sydney have now daily and nightly opportunity of indulging in ice-skating, under most comfortable conditions.

— Sydney newspaper, August 7th 1907. Caption to main image above. [15]

Skating on the ice in Sydney! How strange it sounds! There are many readers of the "Sydney Mail" in whose minds a train of happy memories will be called up by the scene which our artist has here portrayed. Memories of glorious outings on lake or stream in the old land, when the heart was young, and there was thought of nothing but the enjoyment of the moment as, in the crisp, wintry atmosphere, they raced along the glassy surface of the ice. No exercise is more exhilarating than this. In our sunny land, Jack Frost wields but little power, and open-air skating is practically unknown. Through the enterprise of the Glaciarium Company, however, the people of Sydney have now daily and nightly opportunity of indulging in ice-skating, under most comfortable conditions.

— Sydney newspaper, August 7th 1907. Caption to main image above. [15]

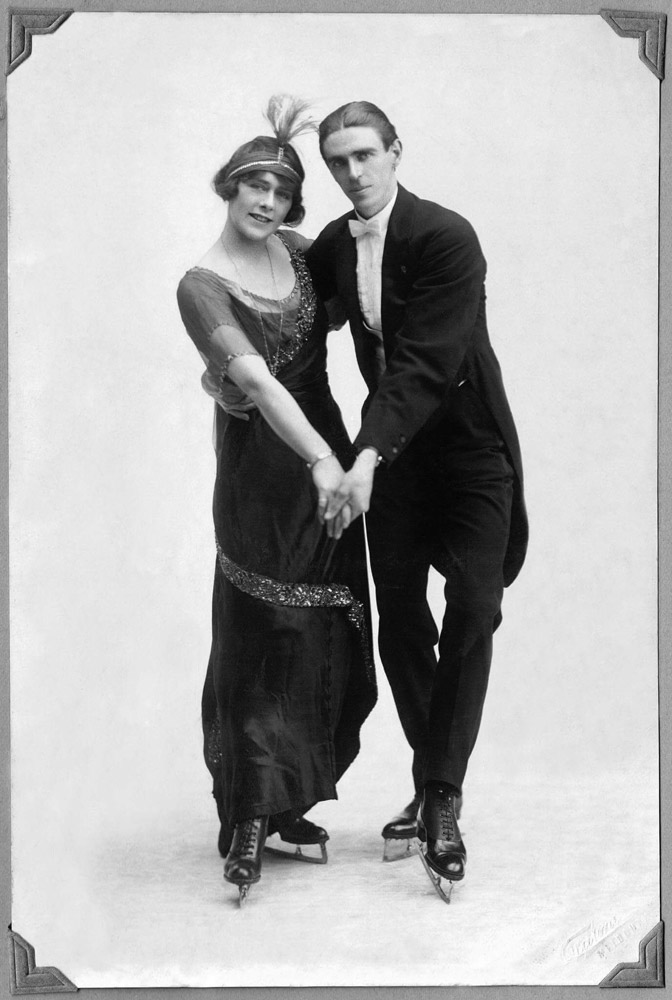

— Billy Clegg and Cyril Macgillicuddy, c1910s. Courtesy Simon Yencken.

— Billy Clegg and Cyril Macgillicuddy, c1910s. Courtesy Simon Yencken.

QUIETLY, LIKE A SHADOW the eyes of two thousand people followed the precision footwork of the ice dancers until two thousand pairs of hands drowned out the last bars of the Australian Orchestra. Professor Langley's young pupil was no older than fourteen or fifteen, yet the grace of her movements had earned her equal applause. Tomorrow, the papers would say so. The week before, Australia won the Davis Cup and Norman Brookes won Wimbledon, the first Australian to do so. On the scale of things, it's not the same, she thought. But in those few, very fine moments, it felt like it. This was their Wimbledon.

Billy Clegg and Claude Langley smiled with a triumphant wave. They were the principal pair of five couples who had traveled up from Melbourne to help at the opening night ceremony. [5] Mercifully, the state premier, Carruthers, delivered the shortest speech of his career, declaring Sydney Glaciarium open and propelling ten skaters into the mazy intricacies of a waltz on skates. [5]

"Curtsy to the dignitaries first", she prompted herself. "Then the stands each side and skate off." A precise geometry of two and three-lobed patterns covered the ice floor around them, the most an expert pair can make. His solo was followed by afternoon tea, and finally skaters took to the ice for the first time in Sydney, many of them already accomplished. [5] Number 849 George Street West at Railway Square in Haymarket was still the heart of Sydney's modern retail district in 1907, and now it was also home to the city's first ice rink.

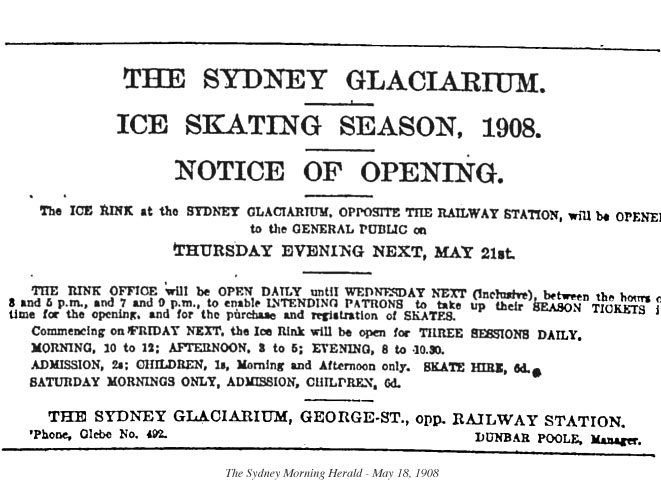

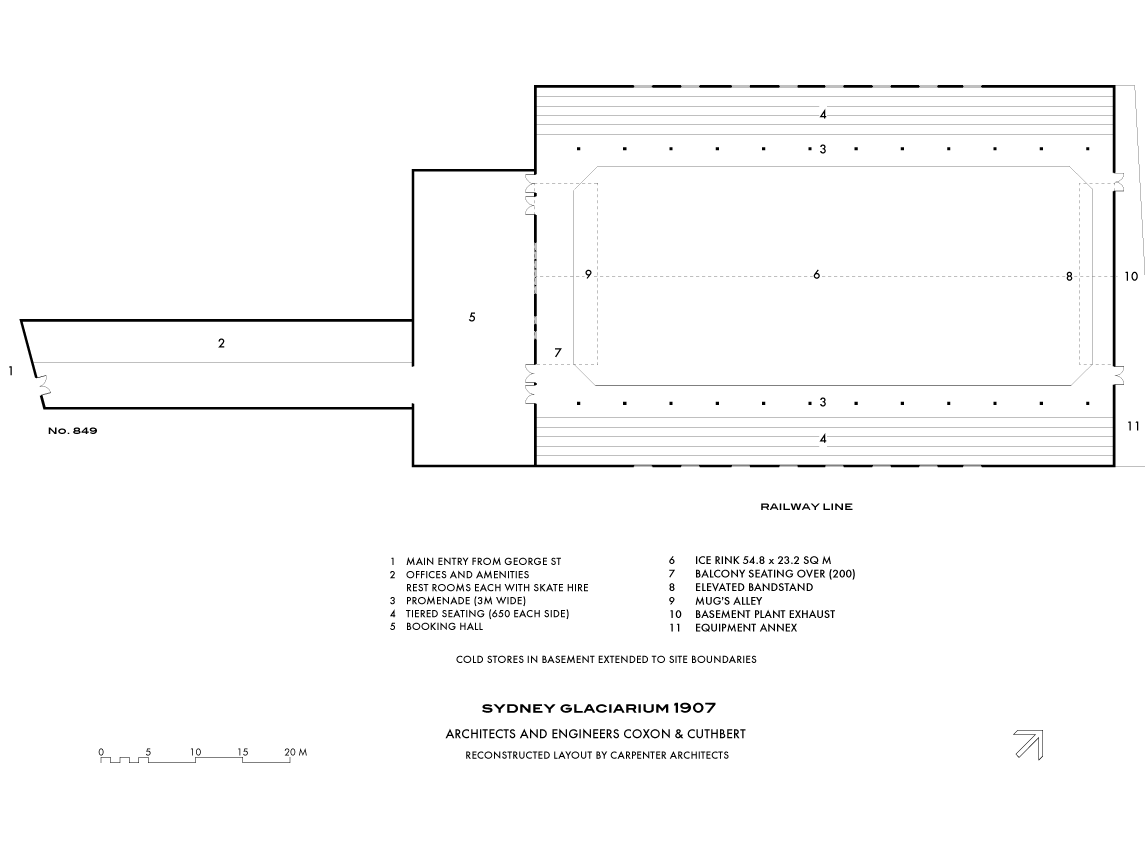

Two days earlier on July twenty-third, Dunbar Poole stood at the George Street entrance ushering pressmen toward the booking hall for the start of a private tour. Accompanying him were the architects and contractors, and the management company's secretary and foundation director, George Buzzacott. Poole, the rink manager, guided his party down a gently sloping passage constructed one in twelve to a nine metre width. Past the cloak room, past the skate room where staff unpacked two thousand pairs, past the offices and the ladies and gents retiring rooms, though the booking hall to the entrance doors of the skating hall beyond.

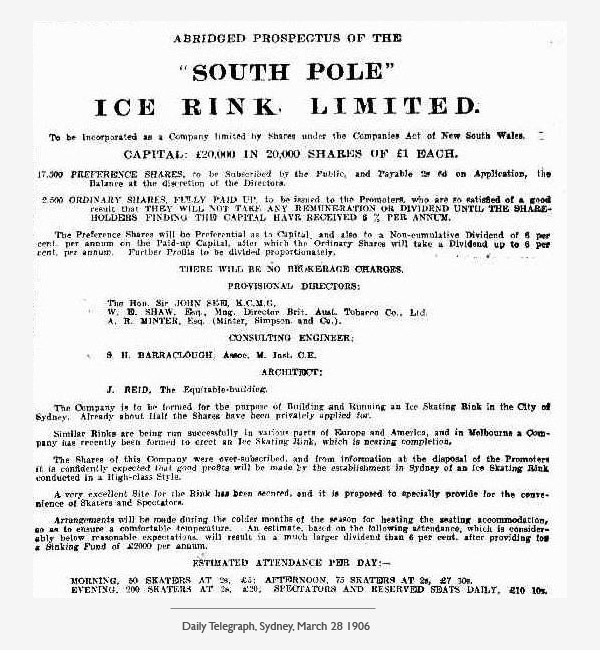

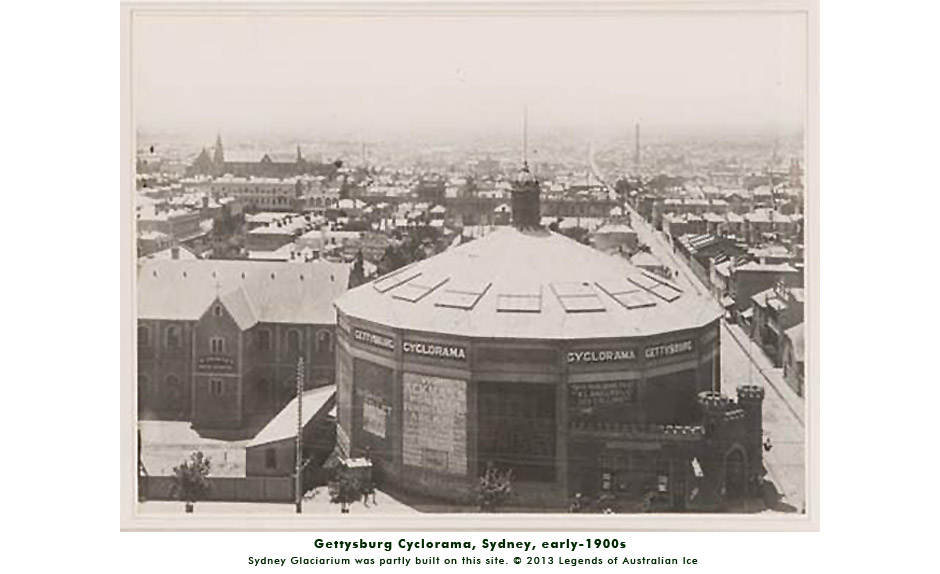

"After 18 years," announced Poole with his back to them, "the Sydney Cyclorama building was unceremoniously reduced to rubble by its last exhibit, The Battle of Gettysburg. Boom! In its place rose a modern new design by architects and engineers, Coxon and Cuthbert, and contractors Baxter and Hepburn".

The builders basked in the reflected glory, the press tensed in anticipation. Then, with all the melodrama a showman can muster, Dunbar Poole threw back the doors and turned on his heel just in time to see the icy chill from the Swiss alpine scene blast his little coterie.

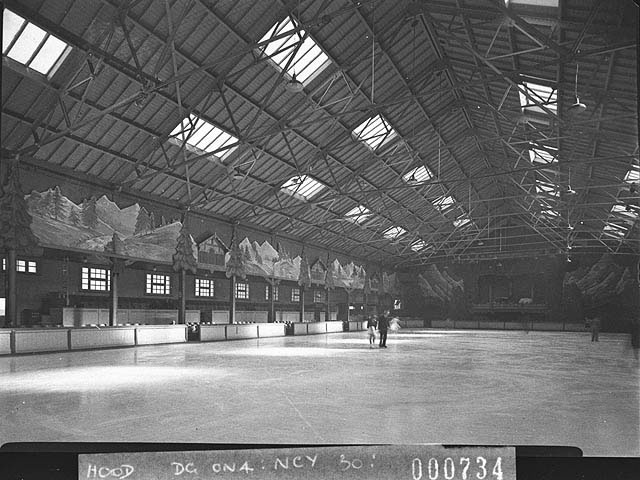

Perched gaily beneath a steel trussed roof soaring fifteen metres above ice, the skating hall was a postcard from Swizterland, the Hall of the Mountain King. Washes of sunlight dripped through high windows in the outer walls, stole in unannounced through the roof lights of every second bay. Shadows here and there only intensified the bath of light. The pressmen scratched and jabbed at their pads, drenched in the pool of gold spilled from the cathedral.

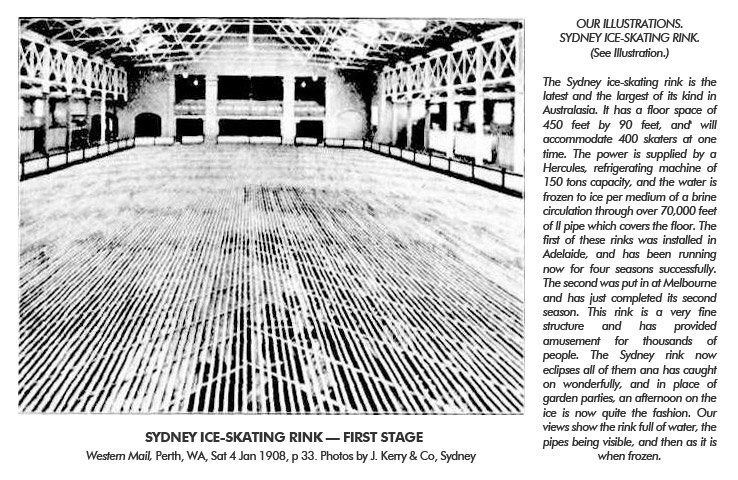

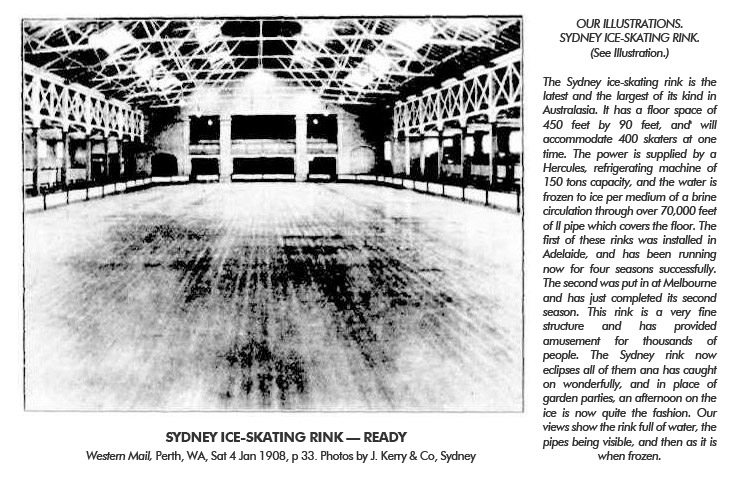

The entire rink hall was sixty-one metres by forty and constructed like the grand sheds of the European rail era. On the end wall hung an elevated bandstand modeled on the world's first Glaciarium in London. But the enormous jewel glittering for as far as the eye could see was most important of all. Stretched out before them for a width of twenty-three metres, lay a fifty-five metre length of iridescent joy. [13]

The ice was hard and crystal clear and, much to the surprise of the visitors, every metre of the eleven or twelve kilometres of piping was clearly visible. A three-metre wide promenade heated by steam pipes ran around the rink giving access to thirteen hundred spectator seats. A small gallery at the end seated another two hundred for an uninterrupted view over the entire floor.

"Like it's Melbourne forerunner", explained Buzzacott to the group of writers and artists flipping pages in pads, "Australia's third ice rink is built over the freezing plant of the Sydney Cold Stores which naturally provides the ice surface and heats the seating and service areas".

Buzacott was a dignified yet unimposing man, the kind you might expect to find as a confidante to a king or his butler. A prominent Sydney sharebroker, he sometimes worked with the even more prominent Fred Thonemann and his Melbourne stockbroking firm. When Fred died in 1939, he was the oldest member of the Melbourne Stock Exchange and very well-known in business circles throughout Australia. By 1988, the former Melbourne City Councillor's firm could celebrate a century of the same name and partnership structure, something only J B Were had achieved in the finance industry up until that time. [4]

Fred owned big cattle stations in both states when he publicly floated the Sydney Ice Skating Rink Co, his first project in that city. No stranger to ice works, his son Jim played ice hockey with Dunbar Poole against American sailors in Melbourne the year before, and soon they would play Sydney's first ever ice hockey games. Because Fred was bankrolling it, and because the rink in Melbourne by H Newman Reid was his model.

As Punch newspaper in Melbourne put it, "A little coterie of businessmen are running the Glaciarium, but they are not relying for their dividends exclusively upon the unwieldy person who pays two shillings admission, and then sit down suddenly." [3] Underneath the ice rink was a huge frozen storage space for thousands of refrigerated carcasses of mutton, destined for the wharf via the railway station next door. "All the dear little lambs will not be deporting themselves on skates on the magnificent ice rink..." concluded Punch. "Some of them will be hanging by their heels on hooks on the underside, waiting to be sent off to the hungry millions always clambering in London for something to eat." [3]

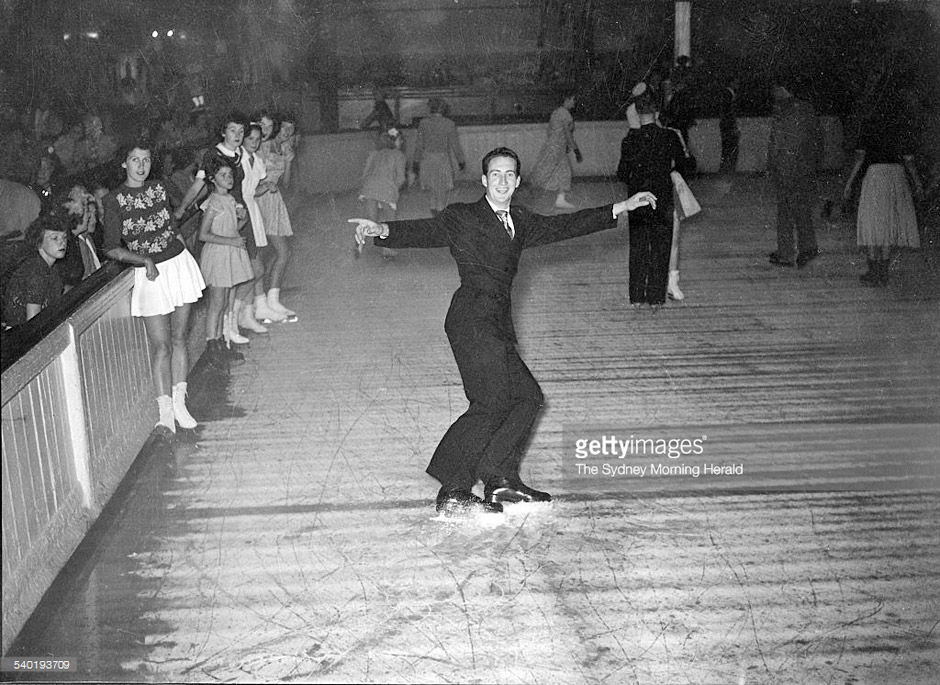

Professor Claude Langley from the Academy of Skating in Melbourne was one of the first instructors at the Sydney rink, and probably its principal instructor. He was 23 years-old when he and the first batch of Melbourne ice skating pupils performed the figure skating exhibition at Sydney Glaciarium on July 27th, two days after it officially opened. Among the students were the young Reids — Hal, Andy, Leslie and Mirey — children of the founder of the first Australian ice rinks and ice sports.

Langley was present when all three rinks were founded in the three states, and it was the time he spent with Professor James Brewer in Adelaide and Melbourne that changed his life. Enthralled by the Professor's exhibitions, he decided to become a great skater, learnt all he could from Brewer, then traveled to Europe in 1906. A few years later in 1910, he earned his Bronze Medals at Princes Skating Club at Knightsbridge in London, Brewer's home ice, then Gold, Silver and Bronze at Davos in Switzerland in 1911. He was probably the first Australian to ever achieve some of the most demanding benchmarks of ice skating proficiency in the world.

From the opening of the rink until the war, Langley often visited Sydney to showcase "fancy" skating, sometimes with a young female pupil from Melbourne as his ice dancing partner. He also helped organise the earliest hockey on ice practice matches in Sydney. The city's first or second match in the opening celebrations used a ball, and matches continued at regular intervals in Sydney that year, usually played at 10:15 pm, after the general skating sessions. Poole billed them Hockey on Ice - Black Team versus White Team. An exhibition match between Victoria and New South Wales a few months later on August 5th, resulted in a win for the home team, three-zero.

Langley's opening night partner, Billy Clegg, was a first cousin of John Goodall of ice hockey Cup fame. Her "waltzing was a joy for both partner and spectator in the years just before the First World War at Prince's," wrote British Skater Joan Dean, "where she attracted great attention and with whom we all wanted to dance". [14]

Young Billy wanted to be good at skating, good at every challenge, but she did not need to win. She did it because she could, just for the accomplishment. In 1913, at the age of twenty-one, she was the third ladies' skating champion of Australia during the years the association in Sydney did their own thing. Ranked among the top Australian skaters of her time, she was exquisite at dance and free skated comparably with Mirey Reid, Doris Armitage, Merna MacGillicuddy, and Sydney's Fannie Trotter.

Fannie later married the Melbourne skater Ramsay Salmon after Poole and he moved to Sydney. All three were close friends and in 1914 Fannie was the first Australian woman to compete in the figure skating world championships. She represented Sweden like Dunbar Poole. The Salmons and Charles Maclurcan were very influential in the local skating world during these first years.

All three later became skating Gold Medallists overseas, and all held seats on the first board of the National Ice Skating Association of Australia in 1931. It took that long for the two States to finally rise above decades of debilitating rivalry and infighting, despite the congenial first night in Sydney. It was as if the skaters of Sydney had to first prove to themselves they could stand on their own.

Over the following weeks, the sight of eight hundred skaters on the rink at one time was not uncommon. [11] Poole arranged sports and entertainments such as hurdle, obstacle and other races weekly, a children's carnival and bal masque. [11] Instructors continued to arrive from London each year, sometimes exhibiting at both rinks in Melbourne and Sydney.

Some of the carnivals organised by Poole were quite spectacular for their time. Richly costumed grand parades, processions of sleighs decorated with electric lights, exhibitions of expert pair skating, and burlesque hockey matches. Sometimes hundreds of electric lights decorated the roof, sometimes threads tipped with balls of wadding like a snow-storm, flags and banners draped everywhere.

The Ice Skating Club and the Glaciarium Ice Hockey Club soon set up shop, but not without start-up challenges. "Mug's Alley" at the entrance end of the rink was equipped with a steel handrail for beginners, embedded in the ice about a metre in from the boards. Large mirrors installed above the boards in Mug's Alley aided the training of skaters, but like the rail they were dangerous for hockey. Posts between the boards surrounding the ice protruded five centimetres, sending pucks ricocheting wildly around the rink. [1]

Nonetheless, ice hockey quickly developed and in the second season on August 26th, a team from a visiting American Fleet defeated a local team selected from patrons of the rink by five goals to one. [8] A wood puck was used in the game. [9, 12]

The following month, the Fleet played a 3-match series against the Victorians in Melbourne. Contested with 5-men a side due to a shortage of American players, the home team won 9-2, 6-4. In 1909, New South Wales sent its first team to Melbourne for the inaugural interstate championship, now known as the Goodall Cup. Four years after the rink opened, the Sydney Ice Hockey Club established the first three local ice hockey clubs — Ottawa, Corinthians and Wanderers. [10]

When the rink closed many years later in 1955, the local skating community drew a collective breath. They hung their heads. First in grief, then disbelief and finally respect. Of the buildings flanking the rink's original entry on George Street, Wembly House still exists and the shops at 849-855 are now a protected heritage place. The airy rink hall at the rear is gone.

It was many years before a replacement rink arrived, and nothing ever really filled the gap The Glaci left. Over the first thirty years there, the skaters of Sydney produced the State's first national men's champion, the first Australian woman to compete in a world figure skating championship, Australia's first international ice hockey player, and its first Winter Olympian.

THE MAN IN THE MORNING COAT and handlebar moustache looked sartorially elegant bathed in the backlight of the projector. Short waxed hair brushed back from a high forehead, bestowed on him an air of intellect not usually associated with Edwardian showmen. But he was a new breed — half concert promoter, half film exhibitor, with touches of vaudeville and circus rolled in for good measure.

Among the first pioneering entrepreneurs of a burgeoning industry, his career began as a press agent for Barnum & Bailey, until he struck out on his own as an optical lanternist in Edinburgh. He also exhibited scientific novelties such as X-rays and moving pictures during the silent film era.

After the first skating season finished in October, T J West temporarily covered his leased ice floor for theatre and dance, and hired Lou de Groen's Vice Regal Band. [6] West's Pictures opened on Saturday December 7th with a house of thousands. Among the first films shown there were Winter Sports in Sweden, the Casa Blanca War, Agricultural Australia, Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves, and South African Diamond Mines. [7] His holiday screenings became a runaway success.

Popular in the theatrical business, West was the first to show films in Sydney at the Lyceum, but he was not limited to that. His screenings incorporated concerts and vaudeville and he was even responsible for oddities such as the first Commonwealth beauty competition in Sydney in 1911, won by the Australian actress, Vera Pearce.

Thomas West continued screening films at the Glaciarium for ten off-seasons until early-1916. He died in England on November 30th that year. Hoyts Theatres absorbed his company many years later.

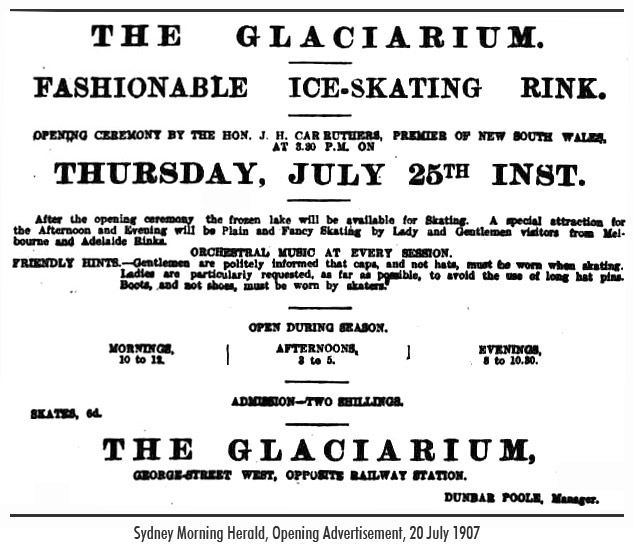

[1] The Sydney Morning Herald, 20 Nov 1906, p 11. Buildings and Works.

[2] Australian Star, Sydney, 24 Jul 1907, p. 2.

[3] Punch, Melbourne 25 Jul 1907, p 3.

[4] The Age, Oct 26 1988 p 29.

[5] Australian Star, Sydney, 26 Jul 1907, p. 8. The pair exhibition was Billy Clegg and Claude Langley. The Victorian pairs in the opening waltz were: Molly Atherton and Jim Thonemann, Winnie Williams and Ramsay Salmon, Miss Peacock and Gordon Langridge, O Atherton and Claude Langley, Billy Clegg and G Smith.

[6] Sydney Sportsman, Surrey Hills, NSW, 4 Dec 1907, p 2.

[7] Op Cit. 11 Dec 1907, p 2.

[8] Evening News, Sydney, 27 Aug 1908, p 8.

[9] The Daily Telegraph, Sydney, The Fleet Triumphs, 27 Aug 1908, p 9.

[10] "Ice Hockey: The NSW Ice Hockey, Association Inc. Australia - Facts and Events 1907-1999" by Sid Tange (1999). 175pp. unpublished manuscript; Extracts published in 2007 on the IHNSW web site for the 2008 Centenary.

[11] The Sydney Mail, 7 Aug 1907, p 342. Skating on Ice in Sydney.

[12] The Argus, Melbourne, 2 Sep 1908, p 4. Americans Play Victoria.

[13] The Sydney Morning Herald, 30 Jul 1907, p 4. Buildings and Works.

[14] History of Ice Skating, Joan Dean, London, 1956.

[15] The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser, 7 Aug 1907 p 305.

Aerial View 1949

KEY | A. Former Cyclorama | B. Glaciarium | C. Former King's Theatre, buildings + shops | D. Agincourt Hotel | E. Shop at No. 851 | F. Glaciarium access on George St | G. Glaciarium booking hall | H. Wembley House over railway | I. Marcus Clarke, former Bijou Picture Palace \ Princess Theatre | J. site of the infamous central square theatre | K. Empire Theatre - Her Majesty's Theatre | L. Lyric - Forum Theatre | M. Haymarket Theatre | Chris Hampton, 2012

Aerial Detail 1949

KEY | A. Former Cyclorama | B. Glaciarium | C. Former King's Theatre, buildings + shops | D. Agincourt Hotel | E. Shop at No. 851 | F. Glaciarium access on George St | G. Glaciarium booking hall | H. Wembley House over railway | I. Marcus Clarke, former Bijou Picture Palace \ Princess Theatre | J. site of the infamous central square theatre | K. Empire Theatre - Her Majesty's Theatre | L. Lyric - Forum Theatre | M. Haymarket Theatre | Chris Hampton, 2012