The Stride of Giants

Graham Argue and the rink entrepreneurs

![]() The game itself is one of the fastest and most spectacular around, both to play and to watch. It's progress though, has always been retarded by its administration and by lack of good liaison with the rinks.

— Graham Argue, President, Australian Ice Rink Operators Association, Melbourne. [1]

The game itself is one of the fastest and most spectacular around, both to play and to watch. It's progress though, has always been retarded by its administration and by lack of good liaison with the rinks.

— Graham Argue, President, Australian Ice Rink Operators Association, Melbourne. [1]

![]() What a great moment for Ice Hockey in Australia at the time, and [right] when we needed an injection for the sport.

— Elgin Luke, Coach of Team Australia, July 2017.[12]

What a great moment for Ice Hockey in Australia at the time, and [right] when we needed an injection for the sport.

— Elgin Luke, Coach of Team Australia, July 2017.[12]

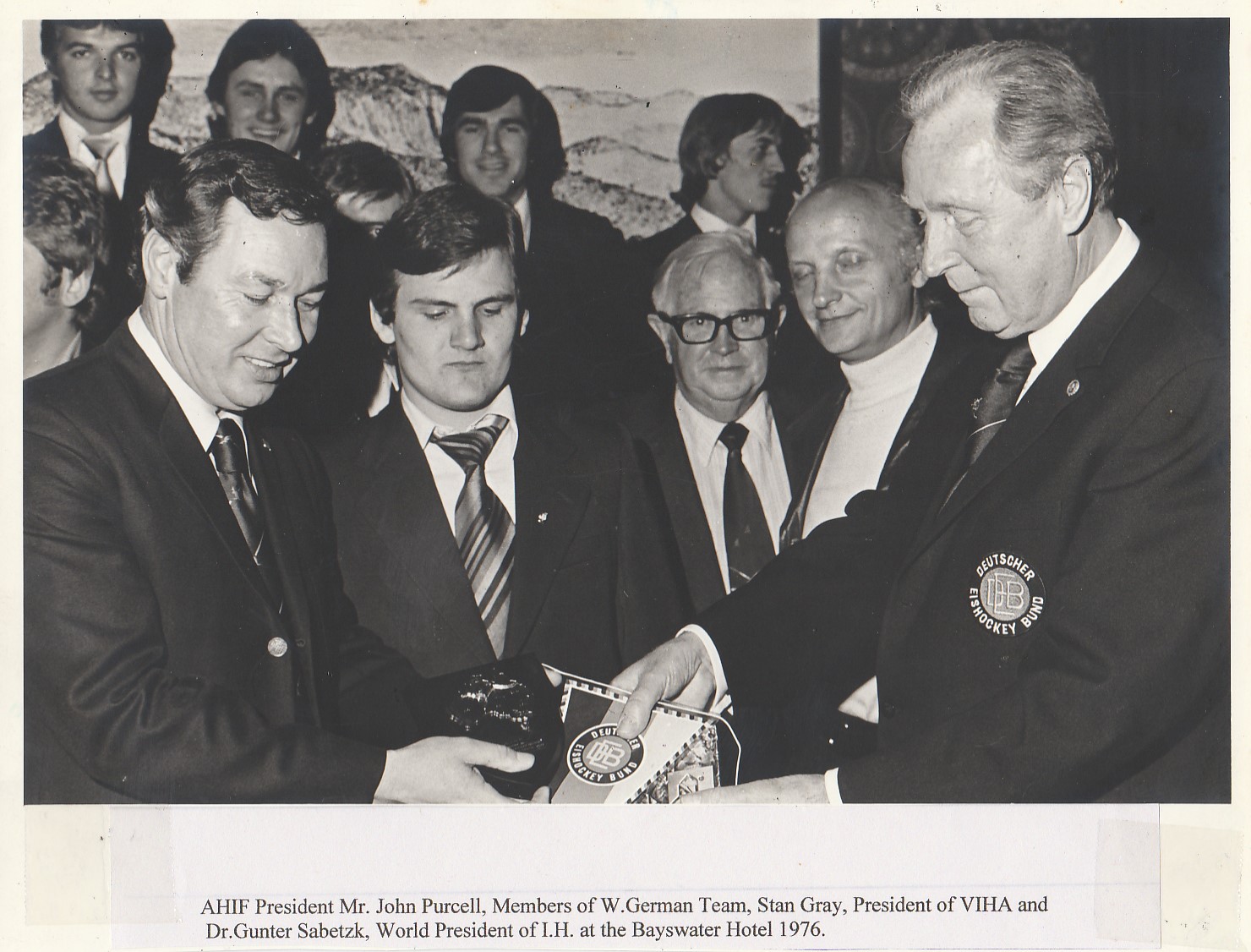

Image: President of the AIHF, John Purcell (centre), presenting a commemorative plaque to the president of the International Ice Hockey Federation, Dr Gunther Sabetzki, watched by Tony Martyr, manager of the Bayswater Hotel where the presentations were hosted. Courtesy Tony Martyr Jnr. [1]

Image: President of the AIHF, John Purcell (centre), presenting a commemorative plaque to the president of the International Ice Hockey Federation, Dr Gunther Sabetzki, watched by Tony Martyr, manager of the Bayswater Hotel where the presentations were hosted. Courtesy Tony Martyr Jnr. [1]

IN THE WHISPERING ARCHWAY of the Burgriesenhaus, I am a little disappointed to hear no murmured sweet nothings on my departure. My Lonely Planet guide and I have fallen out of love, and all over broken promises. The Castle Giant's House, commissioned by Archduke Sigmund for a court giant in 1490, did seem an unlikely site for romance and I am, after all, en route to a different house, a different kind of giant. All along the way, the beautiful vistas of the huge ring of mountains keep me company as I descend deeper and deeper into matters of the heart. To the north rise the jagged peaks of the Nordkette in the Karwendel range. To the south, above the wooded Bergisel ridge, are the 2403-meter Saile and the Serles group. And to the southeast, above Lanser Köpfe, lies the rounded summit of the 2247-meter Patscherkofel so popular with skiers.

Here, in the semi-circular quarter of Oldtown, enclosed by a ring of streets known as the Graben, the narrow, twisting roads are now pedestrian-only, a necessary condition, I think, for a stroll through eight hundred years of history. Instead of motors, the place is brimming over fine examples of old Tyrolese architecture and southern influences, along with sumptuous Renaissance, Baroque, and Rococo buildings. These narrow house-fronts are handsome doorways are both complicit in the deed. So too these oriel windows, these buttressed medieval houses, and these arcaded-façades. All conspired to replace the motor traffic of Oldtown with the foot traffic of people consumed by wanderlust, with people much like me.

Approaching the Olympiahalle of the 1964 and 1976 Olympic Winter Games, I marvel over the crowds it draws all these years on. It is still the scene of national and international winter sports competitions every year. The finest moment in all of German hockey history took place here at Innsbruck's Olympic arena, a 4-1 victory over the United States on the last day of competition at the 1976 Winter Olympic Games. Three goals from a scattergun of twenty-two shots in the final frame propelled the West Germans to the bronze medal, and the man who set up all three was also a giant of his era, the six-foot-six Erich Kuehnhackl.

Of the three nations deadlocked in third place, West Germany benefitted most from the new tie break rules. Discarding the traditional goal differential of all games, officials used only the results of the deadlocked group. It is still done that way today, but the Finns felt hardly done by, the Americans muttered about losing battles to win the war, and the Germans led by coach Xaver Unsinn accepted all of it with glee.

West Germany's ice hockey team first competed in the Winter Olympics in 1952, finishing 8th. At the next three, they competed as the United Team of Germany, then separated again to finish seventh at the 1968 Games. Germany never won an international ice hockey competition, and the nation is still not considered as élite as the Big Six, but they went as high as seventh in the IIHF world rankings, and never lower than thirteenth. Their 1976 Olympic bronze was a shock, but an even bigger one awaited them on their tour of Australia the next year.

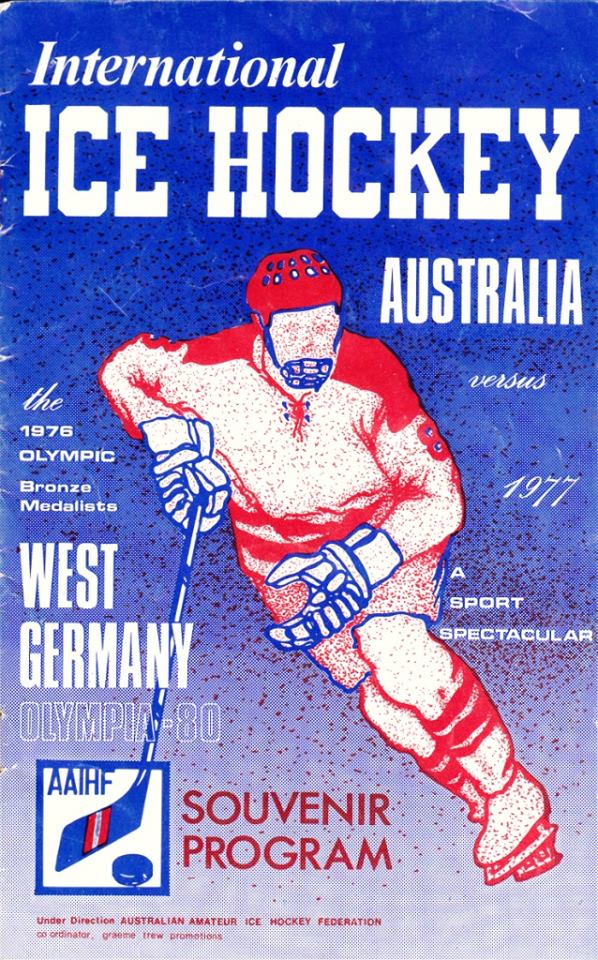

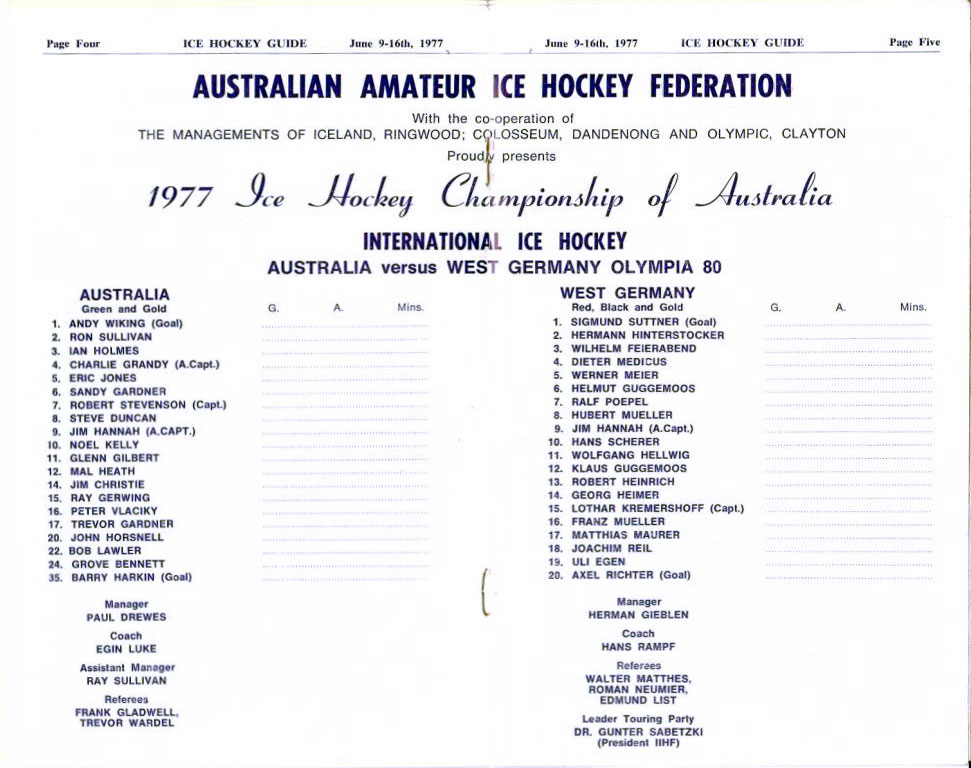

Known as "Olympia 80", the 1977 West German team were players picked to train for the 1980 Winter Olympics at Lake Placid USA a few years hence. Some like Franz Reindl and the goalkeeper Sigmund Suttner were already in the national senior squad, but most were former members of the Junior National Team who did well in World and European junior events. Reindl had played in the Innsbruck Winter Olympics, two world championships, and twenty-eight national games. [11]

Coach Hans Rampf, a former 101-game national team player, became national coach a few weeks before the tour. [1] He played the first of his seven IIHF Worlds in 1953, and won the silver medal at the 1963 Worlds. He was also a veteran of the 1956 Winter Olympics and the 1960 Games at Squaw Valley USA where Australia first competed in Olympic ice hockey. [2] Herman Gieblen managed the team and Dr Gunther Sabetzki, one of the sport's top dignitaries, led the touring party, which included three referees.

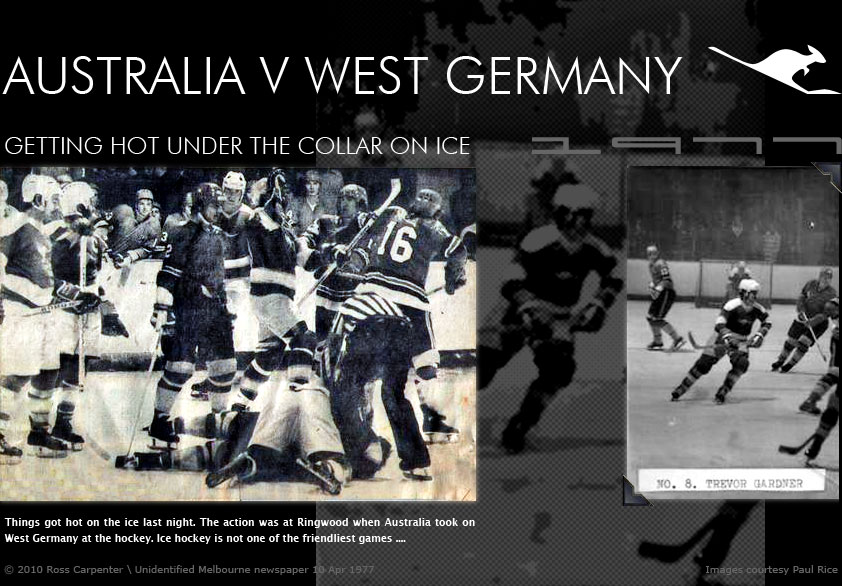

A founding member of the German Ice Hockey Federation, Sabetzki was the first German elected president of the International Ice Hockey Federation. The renowned European referee Walter Matthes also traveled with the team, and even ran seminars for the Australian referees, including Frank Gladewell and Trevor Wardel. Things got hot when the Olympia 80 ice hockey team played a series of six games in Australia, but the pot boiled over many months earlier for the tour organisers in Melbourne.

In the years leading up to this international, the Australian ice hockey scene often suffered administrative breakdown, and most of it stemmed from the actions or inactions of state and national controlling authorities. In Brisbane, the rink management barely tolerated the sport for years, "mainly because of the behaviour and attitude of players". It took "strong words" from the local rink directors to restore a modicum of respect, [1] then a more orderly running of the 1977 season created an exciting window of opportunity, and the State won its first Goodall Cup later that year.

In Sydney, the rink at Canterbury continued to run. Two years earlier in 1975, Burley's company took out a 10-year lease of the Council's open-air ice rink at Prince Alfred Park, and roofed it to boot. A new rink opened at Phillip in Canberra (1976), followed by more new rinks at Narrabeen in Sydney's northern suburbs and Newcastle in 1977. Despite four rinks in the State and a fifth in the Australian Capital Territory, ice hockey was stagnant and it had been for several years when a division in the state association again reared its head.

By 1975, a new controlling body, the Eastern Australian Ice Hockey League, operated in opposition to the long-established New South Wales association. In 1977, the year of the tour, a board of control set up as an umbrella organisation, bridging the divide with limited success. [1]

Further south in Melbourne, the Gallaghers opened the Colosseum at Dandenong, the city's fourth rink. Although the New South Wales-ACT bloc had more ice rinks, Victoria at this time had the best ice hockey scene with twenty-three Melbourne teams playing in three separate competitions. [1] The Victorians led by Kurt Defris considered their 1977 season "The Year of the Youth", and rightly so, because by then all the senior clubs, including the new Dandenong Lions, supported an Under-16 team. [1]

"Enthusiasm and willing assistance have replaced the apathy shown in past years by senior players and officials towards junior hockey,' reported the association. [1] The new Under-16 club competition was one of the legacies of Kurt Defris, who was by then in the second-last season of a record 17-year term as state president. John Purcell, the state's senior vice-president, [10] was also serving a second term as head of the national association. [7] Realistically, that was not possible, too many hats. But "no suitable volunteers" was the common rebuttal, even when there were. The national secretary was Victoria's Stan Gray. [10]

On the eve of the West Germany tour, Graham Argue sat down to write the editorial for the newsletter of the rink operator association. He was its national president and a co-owner of the Olympic Ice Skating Centre in the Melbourne suburb of Oakleigh South. "Breakdowns in the sport always seem to occur at the administrative level," ran his theme. "At a rink operator's meeting in Sydney on May 18, the managements of all the major rinks except St Moritz, which was not present, expressed a complete lack of confidence in the Australian Amateur Ice Hockey Federation's handling of the West German hockey team's impending tour of Australia". [1]

Throughout the season, Argue also assembled and coached the highly talented and victorious Demons team in the local A-grade league. Born in Melbourne in 1929, he was a veteran of 123 games in the Victorian league and a Goodall Cup champion with Victoria in 1951. He married the girl he first met when she was 16. Pat was a professional figure skater, one of six Australian skaters in the Adelaide season of Armand Perren's Ice Follies of 1950 at the Theatre Royal in Adelaide. The couple joined Perren's International Ice Revue touring Australia and New Zealand, then performed in Hot Ice in four states with ice hockey players Jimmy Lawrence and Geoff Thorne.

In London they landed parts in White Horse Inn on Ice, then skated in the Sonja Henie and Morris Chalfen European Holiday On Ice show which toured Europe for three years and South Africa for six months. Back home, the couple raised a family in Elwood and, while Graham returned to the Pirates, Pat skated live on ABC television in ice ballets devised by Nancy Burley from 1957 until 1962. Then they formed the company that built the ice rink at Oakleigh.

Pat directed and choreographed thirteen ice revues there on the small ice, with casts of hundreds of skaters and world champions such as Donald Jackson, Scott Hamilton and Diane de Leu. Throughout the Seventies, the couple also directed and choreographed a mobile ice show called Moomba, and staged ice show promotions at shopping centres Australia-wide, the GMH Motor Show in Sydney and Melbourne, the Adelaide Festival Theatre and Perth Entertainment Centre.

The Argues honed their skills over many years, at home and overseas. By the time of the Olympia 80 tour, they were professional competitors, performers, coaches and rink operators. Their Oakleigh rink was just two-thirds competition size and the focus of the sport in that state had shifted to Ringwood, 23km east of Melbourne's CBD, well away from the state's aging flagship at St Kilda, which slipped quietly into oblivion a few years later. Burley's Iceland at Ringwood was the rink of choice for events like this, the only purpose-built rink in Victoria.

Adelaide and Perth had no competition-size ice. Up north, Brisbane was completely ignored in the venue arrangements for the tour, and Australia's largest rink at Canterbury in Sydney suffered the same fate. "The other Sydney rinks were left in the dark until so late," observed Argue, "that the state board of control was forced to cancel the events altogether, mainly because of the lack of time in which to organise details and finances". [1]

As a result, Melbourne and its new alliance of rink operators were hastily allocated more than their intended four games, just days before the Germans were due to arrive. No time for publicity, no time to arrange official sponsors or guarantors. The players were also kept in the dark on the debacle, and really there would be no trace of it at all, except for the "real facts" published in the rink operators magazine edited by Argue. "The tour is the most important thing that has ever happened to ice hockey in Australia," continued the editorial. "And it could be the last".

The national association negotiations drew out over five months, with only a handful of people involved up until a month before the start of the tour. "This sort of thing could set Australian ice hockey back ten years and make Australia a laughing-stock overseas," said Graham in closing. "The tour is now a fact, so let us try to achieve what we can to make it as good as possible. Let us also realise the weaknesses of our system of hockey administration and do something to correct it". [1]

The international tour did go ahead, but not at rinks around the country as expected. It took place in and around Melbourne, with all the games hosted at three of the city's four rinks. Similarly, most of the Australian national squad was from Victoria. [4]

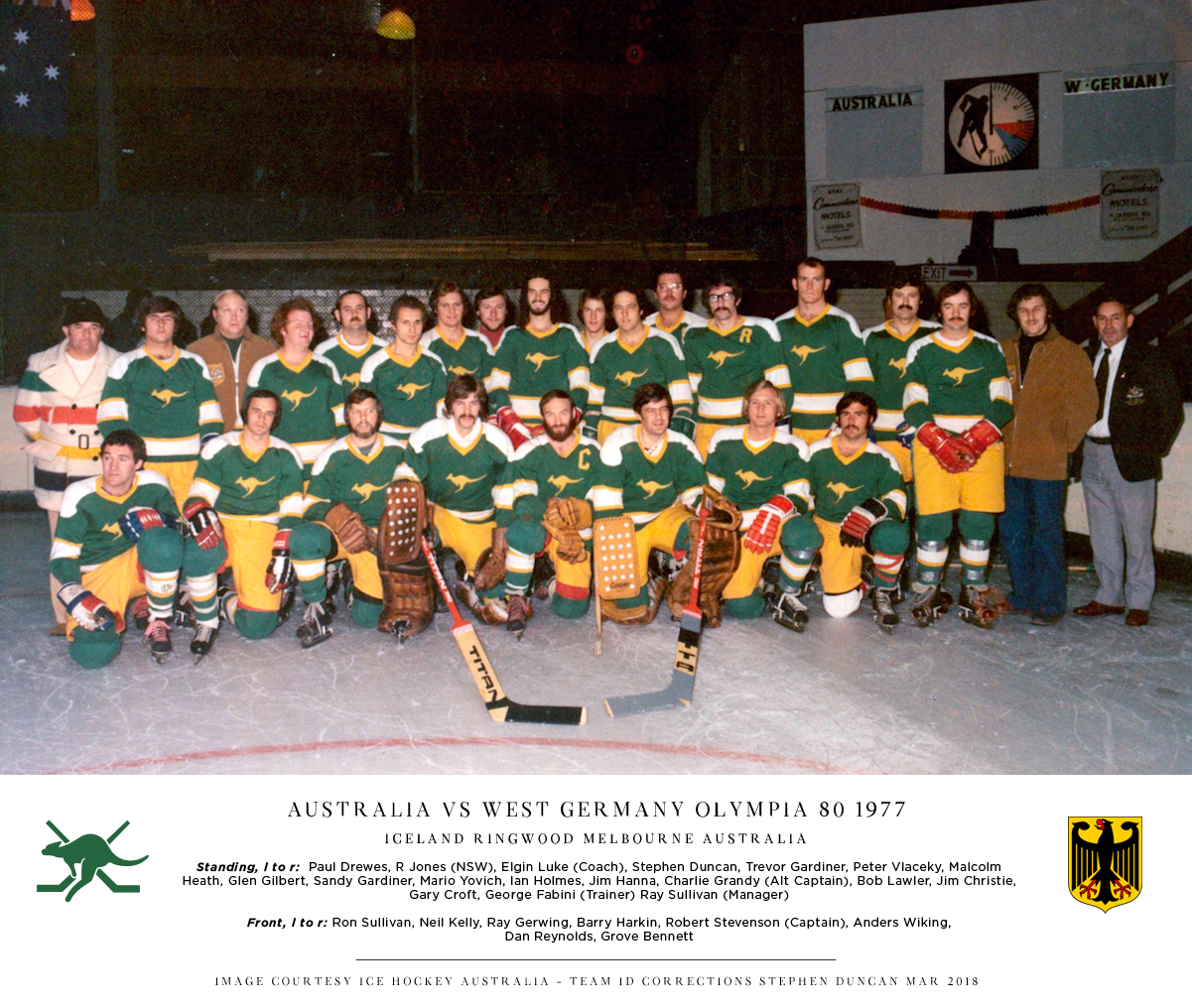

The Australian coach, Elgin Luke, led the Australian team that toured Germany and Holland on their way to the World Championships at Grenoble in France three years earlier in 1974. Paul Drewes managed the home team, assisted by Ray Sullivan. The Australian Captain, Robbie Stevenson, led Great Britain before moving to Melbourne from Scotland a few years earlier, and his Alternates were Jim Hannah and Charlie Grandy. Goalkeepers Barry Harkin and Anders Wiking had both created a big impression when they toured Europe with Luke's Team Australia in 1974.

In the lead up to their Australian visit, the West German team won over Japan, Austria and Italy, and tied two games against Norway. [1] The opening game against Victoria took place at Iceland Ringwood on Sunday June 5th. The next night, the two sides met again at Oakleigh. The West Germans "won the match and the fight", reported the Canberra Times... "the final score was 9-4, and five injured players — all of them Victorians. Captain Robbie Stevenson and Ian Holmes came out of the game with injured shoulders, Neil Kelly a corked thigh and cut eyebrow, John Woodcock a gashed finger, and Ken Guzyk a cut lip. The West Germans escaped injury altogether". [6]

A day trip to Healesville Sanctuary and a barbeque lunch at Maroondah Lake followed, and on Wednesday a trip to the new Mitchelton Cellars at Nagambie, 120 km north of the City. The Germans also visited Sovereign Hill in Ballarat, and on Saturday they were guests of the Victorian Football League at Waverley Park. On the Thursday in between, the first game against Team Australia took place at Iceland Ringwood and resulted in a 15-1 victory for the visitors. [6]

The national association's official reception was held at the Bayswater Hotel, about 15 minutes from the rink. Managed by Tony Martyr, a former Australian national team player, several visiting interstate teams stayed there over the years, including the Germans. Martyr's family lived there, handy to the rink, so handy he was even called on to hastily arrange and chair a Tribunal for an 'incident' during one of the games.

The second game against Australia on June 12th was again hosted at Ringwood, and the third at Dandenong on the Monday. The visitors spent Tuesday on the Mornington Peninsula, and then an invitation-only cocktail party at the German Embassy that evening. The competition returned to Ringwood Iceland for the fourth and last game, West Germany winning, 9-3, to sweep the series. [6] The presentation ceremony at the Bayswater Hotel was a success, then the tourists flew home after a whole fortnight Down Under. [1]

Although coach Hans Rampf guided the West Germany team through four World Championships between 1977 and 1981, he could not repeat the surprise Bronze medal win of the 1976 team at the 1980 Winter Games. West Germany finished the 1980 Games with a 1-4-0 record; tenth of twelve teams ahead of Norway and Japan. [9] The squad did produce good results from one or two games, such as a 4-2 loss to the USA, who were the eventual Gold medallists. Rampf continued to coach the German junior national teams into the Nineties, and the IIHF Hall of Fame inducted him in 2001. [2]

Team Leader, Gunther Sabetzki, received the Olympic Order in 1985, the Order of Germany in 1990, and election to the Hockey Hall of Fame in Toronto in 1995, the year after he retired as IIHF president. The West Germany National Ice Hockey Team ceased to exist after Germany's reunification in 1991. Sabetzki's interest in those countries where hockey was not a sporting tradition helped produce a global expansion of the game during his term as IIHF president. He was a pioneer of the sport's internationalization. [3]

The Argues sold their interest in the Oakleigh rink in the mid-1980s, and although it survives, the couple were lost from the game, along with thirty years of skating and hockey experience. They moved on to produce ice skating for the Victorian Arts Centre at Melbourne's Sidney Myer Music Bowl. Their productions there included Teddy Bears Picnic on Ice for Free Entertainment in the Parks, Rock Concert on Ice for the Melbourne City Council, Young Talent Time Christmas Special and the Telecom Media Launch for mobile phones on national television. They also initiated a school teaching program there and a skating school for the Council of Adult Education.

After three years, the couple sold the business to the Arts Centre and operated a rink at Mount Buller for a season. Graham also helped set up the Melbourne Nite Owls in the old-timer's ice hockey league. He died of a heart attack in 1993, survived by his wife and three children, Greg, David and Michelle. Both boys played ice hockey. The Victorian association awarded Graham Life Membership, posthumously, in 2015.

John Purcell continued as president of the national association until succeeded by Phil Ginsberg in Sydney in 1979. In the quarter-century or so between 1948 and 1975, the schismatic ice hockey administrations of Victoria and New South Wales each produced breakaway leagues. But, while the deep rift in Victoria from 1948 produced a boom decade for the game there, the fracture in the Seventies in New South Wales produced years of depression and an over-reliance on imported players just to stay afloat.

Forty years later, Coach Elgin Luke remembered the tour as "a great moment for Ice Hockey in Australia at the time, and [right] when we needed an injection for the sport". [12] Graham Argue believed it would have been even greater, but for the bungling and mismanagement of the sport's peak body which served only to frustrate the new wave of progressive rink operators.

The amateur and shamateur administrations did not invest in the new professionalism; only in their own empires. Two different organisations worked in opposite directions. One a happy hunting ground of rorters and the status quo; the other progressing on the merit principle where "efficiency is king". One neither politically accountable, nor fit for the task; the other just the opposite. It continued ever onward like a cancer, through the rise and fall of the National Ice Hockey League, to the pale dawn of the quasi-national New South Wales-ACT Super League of the early Eighties.

The Super League turned out little more than renunciation of the Burley-led interstate network of rink operators and their National Ice Hockey League. Flawed in principle and self-defeating, it was inarguably a proxy "national" competition controlled by a single State administration. The only thing worse than stagnation is false progress.

At the national level, the new Ginsberg-Logan administration was motivated to do better things, such as nationalizing junior player development, redefining sponsorship away from alcohol and tobacco, and removing some of the barriers to equal opportunity for women in the sport. These were new foundations after years of depression but, equally importantly, the reforms were also demonstrations of the choices available to administrators.

They strode the world in the Seventies, the West German ice hockey team, and Australian ice hockey might have followed once again. But it was no longer ready.

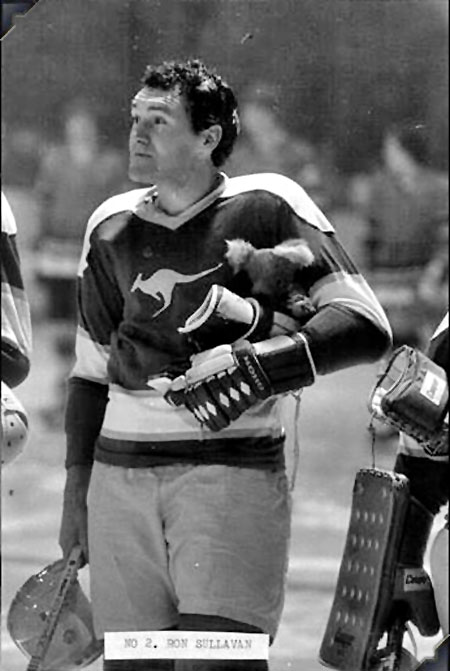

Ron Sullivan, Team Australia, Ringwood Iceland, Melbourne, June 1977. Photo by Tom Kirkham, courtesy Andrew Kirkham. [8]

[1] Australian Skating News, Vol 1 No 3, editorial and cover story, Graham Argue, Australian Ice Rink Operators Association, June 1977. Courtesy Linda and Terry Bishop and Peter Nixon.

[2] IIHF Hall of Fame Inductees, 1997-2006, International Ice Hockey Federation website.

[3] Hockey Hall of Fame, Legends of Hockey, biographical entry for Gunther Sabetzki. Also Sports Hall of Fame Encyclopedia, Vol 1, David Blevins, Scarecrow Press, UK, 2012.

[4] Australia versus West Germany Olympia 80, team rosters, Ice Hockey Guide, June 9-16th 1977, Australian Amateur Ice Hockey Federation. Courtesy Andrew Kirkham.

[5] International Ice Hockey, Australia versus the 1976 Olympic Bronze Medalists, West Germany Olympia 80, Souvenir Program cover, 1977. Courtesy Andrew Kirkham.

[6] Canberra Times, 8 June 1977, p 34; 11 Ju 1977 p 36; and 18 June 1977 p 36.

[7] John Purcell was succeeded by Phil Ginsberg in 1979.

[8] Event Photographs by Tom Kirkham. Courtesy Andrew Kirkham.

[9] For the West Germans, goalie Suttner, Reil and Egen went on to the 1980 Olympics at Lake Placid, won by the USA.

[10] 1977 VIHA Annual Report. In 1977, Kurt Defris led the Victorian administration with John Purcell (Senior Vice-President), Malcolm Heath (Junior Vice-President), Stan Gray (Secretary), and John McCrae Williamson (Treasurer).

[11] 1977 Team Australia were: Paul Drewes (Mgr), R Jones (NSW), Elgin Luke (Coach), Stephen Duncan, Trevor Gardiner, Peter Vlaceky, Malcolm Heath, Glen Gilbert, Sandy Gardiner, Mario Yovich, Ian Holmes, Jim Hannah (A), Charlie Grandy (A), Bob Lawler, Jim Christie, Gary Croft, Ron Sullivan, Neil Kelly, Ray Gerwing, Barry Harkin, Robert Stevenson (Captain), Anders Wiking, Dan Reynolds, Grove Bennett. George Fabini (Trainer), Elgin Luke (Coach), Ray Sullivan (Manager). From the team photo, corrected by Stephen Duncan, March 2018.

[12] 1977 West Germany Tour post, Legends Facebook, June 2017.