DRIVING CHANGE — PROMOTION AND RELEGATION SYSTEM, DICK MANN, SYDNEY, AUSTRALIA, 1971 [4]

In international tournaments, the promotion and relegation principle allows teams from countries in which a sport is less well established to have competitive matches, while opening up the possibility of competing against higher ranked nations as sports grow. The IIHF World Championships are like that. So too, for example, are the world championships for Bandy and Floorball, the UEFA Nations League and the European Team Championships in athletics. The process can continue through several levels of divisions, with teams being exchanged between levels 1 and 2, levels 2 and 3, levels 3 and 4, and so on.

An alternate system of league organisation based on licensing or franchises is used primarily in the USA and Canada. This maintains the same teams from year to year, with occasional admissions of expansion teams and relocation of existing teams, and with no team movement between the major league and minor league. Australian ice hockey adopted a similar system, but usually without even a draft to allocate local and overseas players to teams. The nearest equivalent Australian ice hockey has to a major league is the AIHL. The rest, Association ice hockey, is the nearest equivalent we have to a minor league.

Promotion and relegation have the effect of allowing the maintenance of a hierarchy of leagues and divisions, according to the relative strength of their teams. They also maintain the importance of games played by many low-ranked teams near the end of the season, which may be at the risk of relegation. In contrast, the low-ranked US or Canadian team's final games serve little purpose, and in fact losing may be beneficial to such teams, yielding a better position in the next year's draft. But that is at odds with the principles of competitive balance and improving player performance through higher and higher competition.

The Kiss of Debt

Dick Mann and the EAIHL

![]() During 1975-76, a breakaway body was formed — the Eastern Australia Ice Hockey League. Both bodies ran their own competition until 1977 when a Board of Control comprising the NSW Amateur Ice Hockey president, Mr Paul Drewes, and a representative from the EAIHL, Mr Jack Wallis, was formed with Sub Majsay acting as treasurer. The NSW association was never at any time dissolved.

— Syd Tange, former state and national ice hockey president. [1]

During 1975-76, a breakaway body was formed — the Eastern Australia Ice Hockey League. Both bodies ran their own competition until 1977 when a Board of Control comprising the NSW Amateur Ice Hockey president, Mr Paul Drewes, and a representative from the EAIHL, Mr Jack Wallis, was formed with Sub Majsay acting as treasurer. The NSW association was never at any time dissolved.

— Syd Tange, former state and national ice hockey president. [1]

![]() The present structure of the Goodall Cup is catastrophic, a financial and moral disaster. There is little player initiative in the assistance to "foot the bill" that is expected of the NSW Association. This situation is ludicrous. This interstate series has proved detrimental to the standard of ice hockey in this state and disrupted relationships with rink managements.

— Dick Mann, former state president and rink developer, founder of the Bombers Ice Hockey Club Ltd, Sydney, Australia, 1971. [4]

The present structure of the Goodall Cup is catastrophic, a financial and moral disaster. There is little player initiative in the assistance to "foot the bill" that is expected of the NSW Association. This situation is ludicrous. This interstate series has proved detrimental to the standard of ice hockey in this state and disrupted relationships with rink managements.

— Dick Mann, former state president and rink developer, founder of the Bombers Ice Hockey Club Ltd, Sydney, Australia, 1971. [4]

Number 38 Dover Street Mayfair London. Contemporary photo of the former headquarters of the International Ice Hockey Federation in 1973.

Number 38 Dover Street Mayfair London. Contemporary photo of the former headquarters of the International Ice Hockey Federation in 1973.

I COULD BE IN THE RUE DE RIVOLI, not Piccadilly Arcade. And the exterior of The Ritz London above has too little English architecture to speak of. We should pick apart the origins of a building regarded as a masterpiece from the day it opened, but the Franco-American influences of École des Beaux-Arts graduates in Paris hold little interest tonight. I just admire, then navigate a polite passage through the frescos and gilded statues, the well-dressed Londoners, down the entry stoop, and over busy Piccadilly.

Up the Georgian symmetry of Dover Street, Mayfair, home to the kind of London clubs and hotels that are still favoured by world leaders and historic figures in the arts. Alexander Graham Bell made the first phone call in Europe here at Number 26. Oscar Wilde, Arthur Conan Doyle, Robert Louis Stevenson and Bram Stoker — all regular guests a little further up at Brown's Hotel, on which Agatha Christie based a book.

Number 28 is the house that John Nash moved to, and Number 29 the one he built the next year. You may know him as the architect of Buckingham Palace, but he also did most of the layout of Regency London. The women-only Empress Club occupied Number 35 for a long time, an idea put forward by one of Queen Victoria's Ladies-in-Waiting which received the blessing of the Queen herself.

My destination is a few doors before the place where Chopin stayed in 1848. Number 38 is typical of the houses in this part of town. Complete with a concert room decorated in opulent Victorian style. Like the one next door, still occupied by the Arts Club that Lord Creighton and Charles Dickens founded in 1863.

Because posh is everything here, which might explain why everything important looks Dover Street. From Washington to Williamsburg, Montreal to Melbourne, Neo-Georgian style adorns the homes of the aspiring rich and powerful with a fealty to Britain. An urbanity game of convention and not much invention, played out across the great continents of the English-speaking world.

That's how it was in 1973 when the envelope postmarked "Sydney Australia" dropped through the brass letter slot of Number 38, before coming to rest on the presidential desk of the International Ice Hockey Federation. The Ligue Internationale de Hockey Sur Glace.

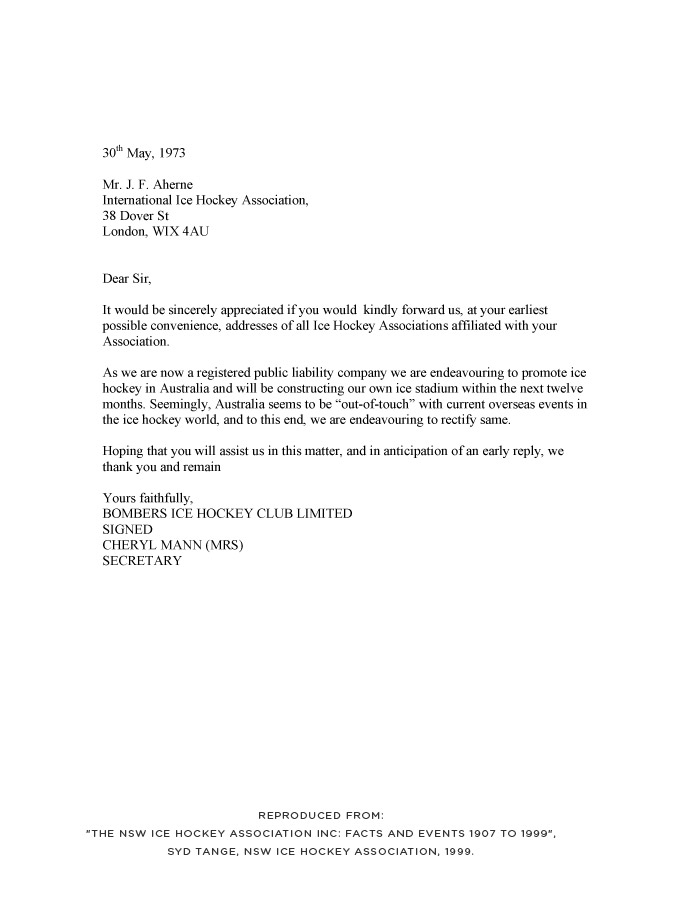

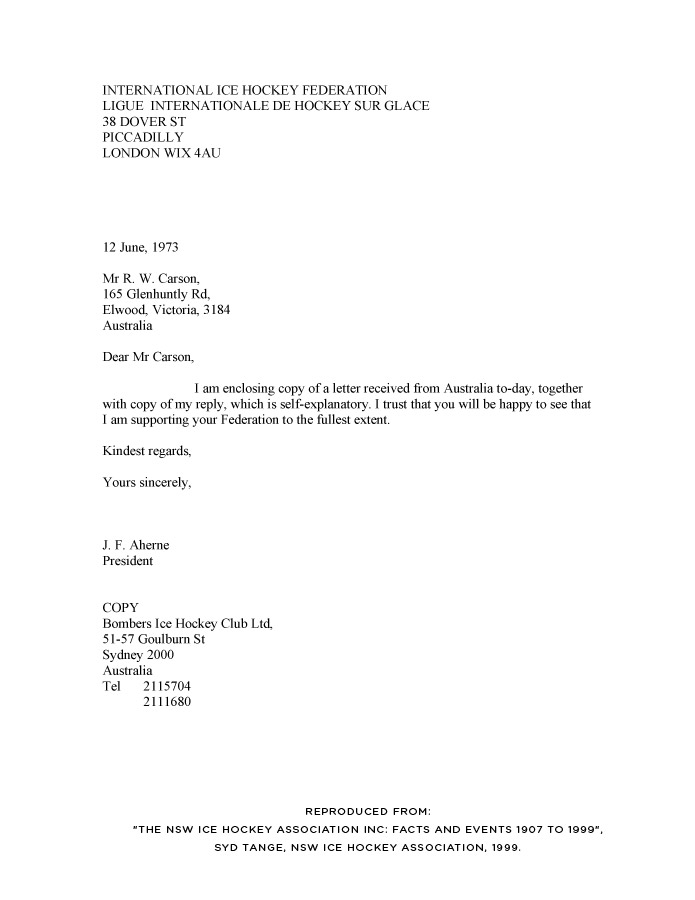

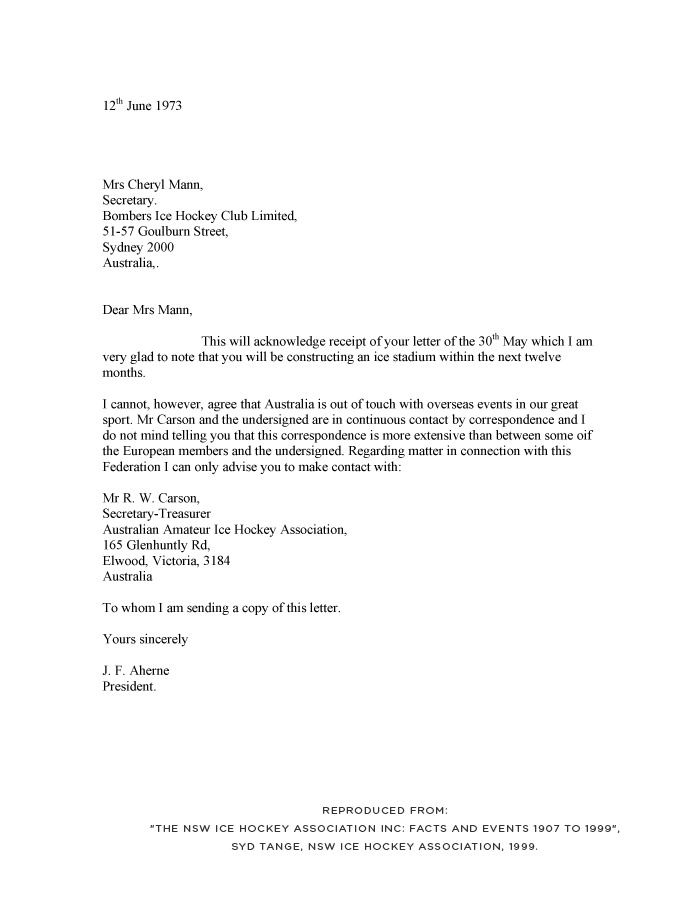

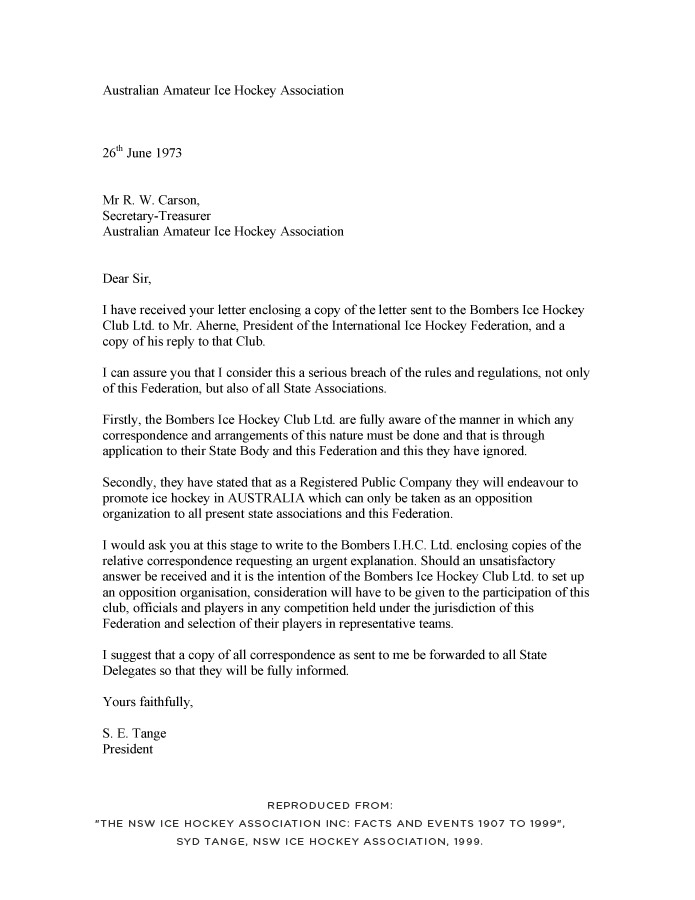

THE FIRST SIGN the Bombers ice hockey club in Sydney intended to take control of the sport into its own hands did not come from the Club. It came from Bunny Ahearne, president of the IIHF, on June 12th 1973. Twelve days earlier on May 30th, the Bombers wrote to the IIHF requesting the addresses of all its member associations. "Australia seems to be 'out of touch' with current overseas events in the ice hockey world," they said "and, to this end, we are endeavouring to rectify same". The Club had incorporated and, armed with a plan to build their own rink within the year, they wanted "to promote ice hockey in Australia". [1]

A short time earlier, the Club offered the use of their City office in Goulburn St for association meetings. They also presented a plan to tour New Zealand and play matches in Queenstown, Christchurch, Auckland and Wellington, then visit Brisbane later in the year. None of these proposals went ahead [1] while Syd Tange, then president of the Australian Amateur Ice Hockey Association, moved to the point in defence of his secretary-treasurer, Russ Carson.

Ahearne pointedly passed the puck to Carson, drop-copying him both letters: "I trust that you will be happy to see that I am supporting your Federation to the fullest extent". [1] In the whitespace, a subtext, a kiss of debt. This one marked a "favour" worthy of a quid pro quo. Next month, the national association told the states its vote at international meetings would be cast by proxy, by Bunny Ahearne. [1] It had happened before, when Ahearne greased the wheels of Australian ice hockey's first and only Olympic bids. [5] This time, Australia returned to the next Worlds, but that and the beneficiaries of Australia's vote is another story.

Mann, who served as state president a few years earlier between 1966 and '68, represented Netherlands in the World Championships in London in 1950, before founding the Bombers in Sydney soon after. He did not elaborate on what he meant by "current overseas events", but the sport at that time was most notable for expansion. "Ice hockey is the fourth largest sport in the western world," he said in a weekly hockey newsletter produced by his Club in 1971. "The standard has remained unchanged in NSW over the last 20 years. The reason for this is no incentive—too many games are 'flat'. Progress is everywhere, though it seems non-existent in ice hockey". [4]

Seven years is a big part of a playing career to be absent from international competition, and it became eleven. The Victorians were still paying back financial debt, while the NHL went from the Original Six teams to twenty-one in 1979, not only opening up the sport to more athletes, but to many more fans in North America. Commercial growth started to put hockey on the map as one of the four major sports, aided by the improved availability of air travel. Players a millimeter from NHL calibre suddenly got a go.

At the same time, Canada's complaints about its top NHL players being excluded from the Worlds fell on deaf ears, while so-called "amateurs" from the Soviet Union, Sweden and Czechoslavakia regularly won medals for their nations. Then, just weeks before the 1970 Worlds was to begin in Winnipeg, Ahearne reneged on Canada's arrangement with the Europeans. It would have permitted Team Canada nine non-NHL pros.

"Canada must fill its roster with eleven amateur players who have never been professional," he declared, claiming the country would otherwise compromise the Olympic eligibility of those who competed against their pros. "This is the agreement I made with the Canadians and that is the way it's going to be". [7]

The OIC refused to back Ahearne's plan, but Canada pulled out amidst angry recriminations, the tournament moved to Stockholm, and the nation did not return to the world championships until many years later when the rules changed to allow NHL pros to take part. The start-up of the WHA in 1972 also exposed the sport throughout North America and across to Europe, while the world saw for the first time just how good the Soviets were during their Summit Series with the Canadian NHLers.

The Canadian press cast Bunny Ahearne as a villain during his first presidency of the British association, as far back as 1936. "A Machiavellian strategist", a "double-dealing, self-serving little rascal". [2] England won both the Olympic and European championships that year, with a roster that included eleven skaters born in the British Isles. But seven had been recruited from Ahearne's list of players who had learned the game in Canada. When Britain did not lose a game, they won the gold medal, with Canada second. The Ahearne years of the IIHL-IIHF were also a money-making venture for his own travel agency. [3] It is no secret. Britain's "little Irishman" cozied up to countries interested in importing talent from overseas. [2]

Up until then, there had only ever been a spattering of professional ice hockey players throughout the long history of the Australian game, and none of them made a living from it. They were just sponsored for a season by rinks, clubs or privately and, though some stayed on, they were not professional players because the sport could not support them.

The best players in Australia were not paid imports. Many were natural post-war immigrants, players such as Tommy Endrei in Melbourne and Dick Mann in Sydney. Then there were the paid rink coaches such as Frank Chase and Bud McEachern, and a few top skaters such as Graham Argue and Geoff Thorne who performed in professional ice shows. But, generally speaking, if players here made money from ice sports, they did so under the counter. Locals paid to play and they paid to represent their country.

"To infer Australia is out of touch with overseas events was, as Mr Ahearne said, incorrect," said Tange. "Mr Carson is a prolific writer and handled an enormous amount of correspondence". Syd told the Club they had knowingly flaunted the regulations by approaching the IIHF direct instead of going through state and national associations. Mann claimed his Club's requests for information from the national association went answered, which Carson adamantly denied. On a motion moved by Stan Gray and Harry Cameron, the national association fined the Bombers $25.00, payable within 7 days. Syd Tange retired in August and Bob Blackburn from Victoria took on the top job. The leadership of state hockey now changed every year or two.

There is no valid point to a commercial comparison of Australian ice hockey and the NHL, not in the early Seventies, not now. There were precious few players of the calibre of the world's top professional league, and it was not practical to import enough to capture a share of a crowded, competitive sporting market, especially without international standard rink infrastructure. No-one has ever stood in the way of that, but the capital investment to succeed over the long haul is not tens, but hundreds of millions.

On the other hand, local competition ice hockey was comparable to some amateur leagues overseas and looking back, few doubted it could be further expanded and its standard improved. Historically, there has also been a general belief that it could be organised better, right up to the limits of the available resources and infrastructure at any given time. That pathway was and still is better national development programs driving higher standards of competition. Leagues designed to progressively expand the competitive knowledge, skills and experience of our sports men and women. Otherwise, Australia is just playing some other nation's league.

Dick Mann argued the Sixties showed a single club could not properly administer both A and B grades in his state. The dissent there began way back when Juniors were all but overlooked, when there was a shortage of players, forfeited games, cancelled games, and a low standard of play, all of which was harmful "to promotion and spectator interest". Unlike Victoria, New South Wales hockey did not even adapt to global post-war rule changes. The lack of excitement and appeal in the sport had indeed become a problem, and Mann believed the solution lay in extending the interstate series for the Goodall Cup, rather than the same four teams constantly playing each other. [4]

This was perhaps the first national league proposal to depart from the traditional interstate series for the Goodall Cup. But its vision was much broader than even that, because it sought to revitalise local competition in both Sydney and Melbourne, by integrating it in a tiered structure with incentives designed to develop players through to the standard required at the top in a proposed new National League. It came nine long years before the next commercialization of the sport in the form of the Pat Burley-led NIHL, and twenty-nine years before the AIHL at the dawn of the new millennium.

"The present structure of the Goodall Cup is catastrophic," wrote Mann. "A financial and moral disaster. There is little player initiative in the assistance to "foot the bill" that is expected of the NSW Association. This situation is ludicrous. This interstate series has proved detrimental to the standard of ice hockey in this state and disrupted relationships with rink managements". [1]

Under the proposal, 2nd Division comprised 4 to 6 new clubs formed from the existing Reserve grade, but divorced from the A-grade clubs. With no more than 20 players, no less than 14, and the emphasis on youth, Div 2 clubs had to supply their own officials and equipment. The 1st Division of 4 or 6 teams could be readily formed from the existing A-grade clubs, with no more than 18 players, and no less than 14.

"To date, the last 2 teams in A-grade have been insignificant," he said, "providing no incentive and dull games". To counter that, the 2nd Division champion should play off against the last team in 1st Division each round, causing team relegation. The winner of the game then plays first Division, and the loser plays 2nd Division. "Competitive interest should result between the last two teams in 1st Division and all teams in 2nd Division". The first 3 teams in 1st Division would then be eligible to play in the new National League, creating incentive between teams 3 and 4.

The top 3 teams in Sydney and Melbourne play the 3 top teams at home and interstate. Points accumulate in the round-robin until all teams have played each other twice. A 3-game playoff series between the top two determines the Australian Champion, the holder of the Goodall Cup. The fixture proposed at least twenty interstate games, instead of the usual three, with about forty-five players from each state competing in National League hockey, instead of a select few.

Mann's competition model determined membership of the National League by a promotion and relegation system. A tiered structure similar to the ones developed in the IIHF and pro sports in Europe, which have been in use since 1888. It is markedly different to both the original "interstate" model of the Goodall Cup, and the North American originated model characterized by its use of "franchises", closed memberships, and minor leagues.

The proposal not only embraced the local grade competitions in each state, it set up a structure to revitalise them, to make them exciting and appealing to fans, through incentives for players and officials—from the junior program, all the way up to the National League. But nothing came of it. Not even in the NIHL or AIHL national leagues decades later. There has never been a league with incentive drivers like that in more than a century of Australian ice hockey. Though well-suited to improving competition, Mann's proposal fell between the cracks of a deep schism that opened in New South Wales hockey, during the years he aligned himself with the new breed of rink entrepreneurs in Victoria.

The next year Australia returned to the World Championships in Grenoble France, this time with a few New South Welshmen and a Queenslander among the Victorians. But any hope of fixing the dissent with that and a $25 fine quickly faded. Pat Burley formed the Australian Rink Operators Association and the Eastern Australia Ice Hockey League sprang up at the Prince Alfred Park and Narrabeen rinks run by Burley and Mann.

Although dissatisfied, the new League's organisers still sought to be affiliated with both the state and national associations and, although Tange reported they received serious consideration, they were an obvious threat to the status quo and a state association now led by former 1960 Olympian, Rob Dewhurst. They were simply told the number of rinks, clubs and players did not call for affiliation. [1]

The Bombers, St George, the Finn Eagles, later Homebush Juniors — all the EAIHL clubs — resigned from the state association. The League's formal request for national affiliation declined, their mediation talks with state officials abandoned, they went one way, and the association clubs the other, among them the Glebe Lions, Canterbury Bankstown, United International and the Hotspurs. They could not work together.

In a genuine attempt to mend the rift later in May, Pat Burley invited the association to play in open competition with the EAIHL and Victorian clubs. New hope for reunification led to an agreement on a joint state team early in 1976, all conditional upon a new "Board of Control" administering state hockey for a trial period. Paul Drewes, the new state president, and Jack Wallis, the League secretary formed the Control Board. [1]

This fragile agreement led to the Australian National Rink Championship [6] amid rumours from Melbourne of a take-over of hockey by the Burley-led rink operators association. John Purcell, the national president, assured everyone he was still in charge, and the championship at least appeared under the control of his association.

Three Melbourne teams, two from Sydney, and one each from South Australia and Queensland, planned to compete in the tournament. It presented an opportunity to pick an Australian team to play against an Olympic training squad from West Germany the following year. Sydney games were hosted at Prince Alfred Park by the EAIHL, and United International won the championship. Tom Lockhardt, the president of the USA association, attended. He happened to be in Sydney on a world cruise. [1]

In June, the state association passed a vote of no confidence in the trial Board of Control. The national association agreed to a stakeholder forum chaired by Purcell at its July meeting, but it too failed. Instead, the meeting delegated the task of solving the dispute to Tange and Wallis. [1]

The NSW Amateur Ice Hockey Association was never dissolved or declared insolvent. It just returned to something resembling normality during 1977 without the word "amateur" in its name. The national association later followed suit, and the word "amateur" has not since re-appeared. Each club retained its reserve-grade players, while Juniors remained affiliated in a separate association. Club delegates voted to elect a state executive of five, with the state secretary appointed from the floor. The executive appointed Drewes chairman and Wallis vice-chairman. Drewes served four terms as president, 1975 to 1978, and was succeeded by Phil Ginsberg. [1]

In a rapidly changing world hockey scene, the Bombers, St George, and the Finn Eagles returned to an Association that had changed little by 1977, its seventieth year. The Homebush Juniors remained outside in a separate league. [1] Dick Mann did open the second rink at Narrabeen that year, and a few years later the Rink Operators did organise an affiliated National League, however short-lived. Also in 1977, two years after Ahearne retired as president of the IIHF, the Hockey Hall of Fame elected him an honoured member, the IIHF allowed all professionals to play internationally, and Canada returned to international hockey.

The breakaway Eastern Australian Ice Hockey League could have been a vehicle for Dick Mann's incentive-driven league proposal. Well-suited to a country like Australia where ice hockey was less well established, it opened up the possibility of competing against higher ranked nations as it grew.

Or it could have been an ultimatum like the local Association thought. Change is hard for some. Especially those for whom success is determined less on the ice, than in the shadowy haunts of a sport's double dealers.

Organisers on both sides of the rift dismissed it, even though it stared back at them from a published newsletter. And even though it required little more time and effort than their outmaneuvering of each other. It slipped into the gaping divide, and forty-five years on one cannot help but wonder about the lost generations. What a less-disillusioned hockey community might have done for the sport.

THE MAN AT THE BAR OF THE RITZ LONDON on my return late in the night, is smoking alone in one of Churchill's favourite places, while somewhere unseen a bar manager is closing up shop. Immaculately turned-out in an old suit from a well-known haute couture house in London, he is short and somewhat pudgy, penguin-like in stature and appearance, and spotlessly clean.

The scene reminds me of something Walter Brown once said. The original owner of the Boston Celtics opened his home to Bunny Ahearne when he visited, but he always had to wait for him to get dressed. [2]

"Now, imagine I'm waiting for you," I say to the near-empty room, half-expecting him to turn with the line.

"I like to put on a garment, have a cigarette, then put on another garment".

I smile and reply: "...I'm going home soon," watching him through the writhing smoke like one watches a snake.

"Got a nice home in Melbourne on the south side of the river. There's a bagelry off Glenhuntly Road, the street where Russ Carson lived. I go there all the time.

"It'll be the first place I go when I'm back in town.

"I'm going to be sitting there eating a Montreal Bagel topped with cream cheese and reading a tiny piece in a magazine. It says you should not be an honoured member of the Hockey Hall of Fame "for fostering the growth of international hockey" ... because you did more harm than good. It says you were discredited for deeds you committed during your time in the sport.

"And then I'll think about this Franco-American building with little trace of English architecture ..... and I'll think about you standing there with that silly look on your face.

"Then I'll finish my coffee, drop the magazine in the bin, and never think of you again".

[1] The Mann-Ahearne letters (image gallery above) are reproduced in full from "The NSW Ice Hockey Association Inc: Facts and Events 1907 to 1999", Syd Tange, NSW Ice Hockey Association, 1999. Courtesy Wendy Ovenden

[2] Squaw Valley Gold: American Hockey's Olympic Odyssey, Seamus O'Coughlin, p 87.

[3] See for example: Net Worth, David Cruise and Alison Griffiths, Penguin, 1992; and Hockey Dreams, David Adams Richards.

[4] "New South Wales Ice Hockey World" weekly program, ed. Cheryl Mann, reproduced in Tange (1999).

[5] Ahearne also held both Carson's and Tange's proxy votes at the IIHF Congress at the 1962 Worlds in Colorado Springs, even though they were both present. Swedish National Archive, Rudolf Eklow and Swedish Ice Hockey Association collections.

[6] This championship should not be confused with the Australian Club Championship contested by the two top clubs in each state.

[7] The Official Site of the Hockey Hall of Fame, entry for Bunny Ahearne.