Mr Hockey

Phil Ginsberg and the lifetime player

![]() Australia is on the right track towards an ice hockey identity of its own and we are proud of the work of Mr Ginsberg and his Federation.

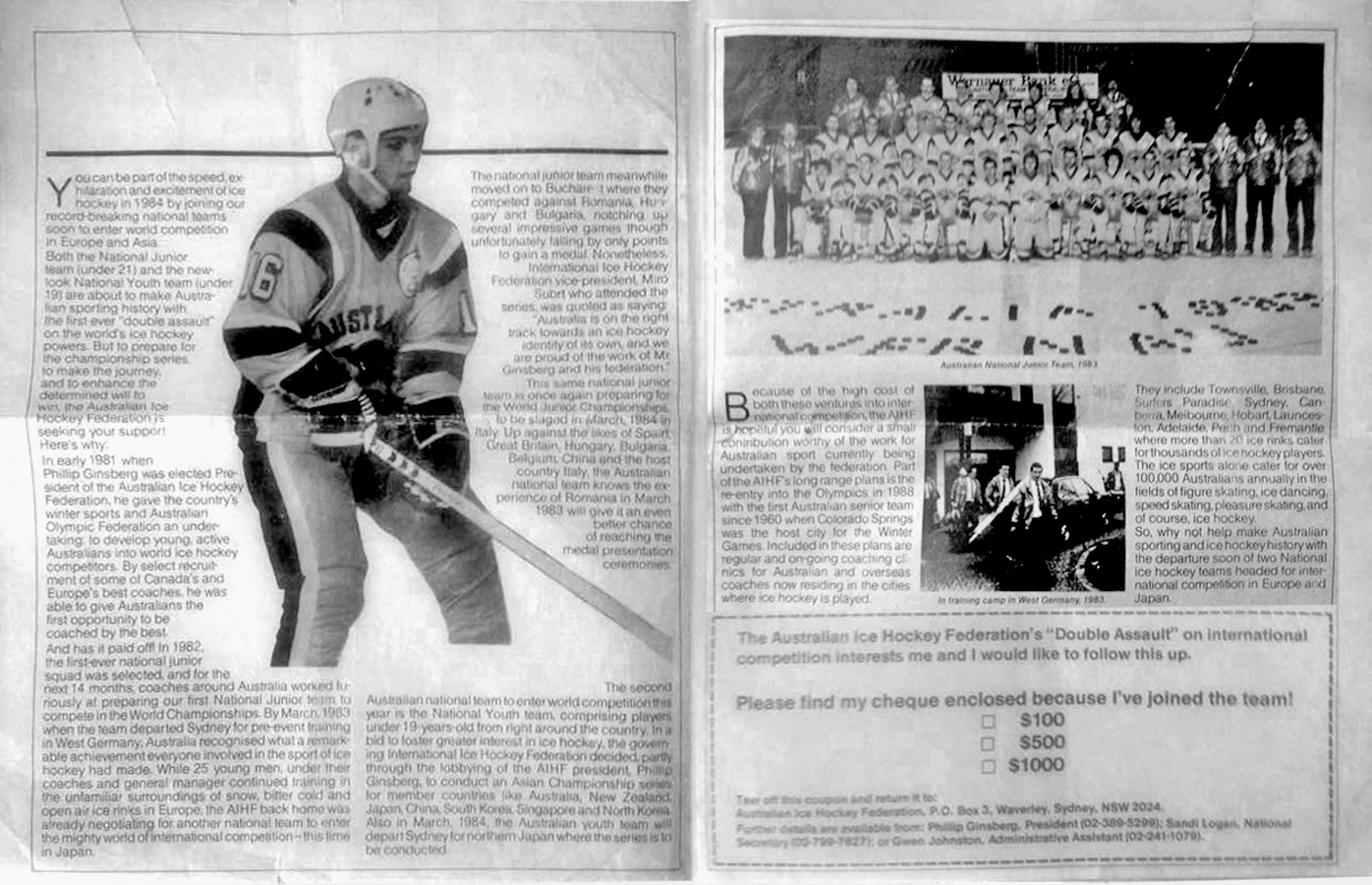

Australia is on the right track towards an ice hockey identity of its own and we are proud of the work of Mr Ginsberg and his Federation.

— IIHF vice-president Miro Subrt who attended Australia's first National Junior Team entry to the new C-Pool World Championships in Bucharest, Romania, on 3 March 1983. [11]

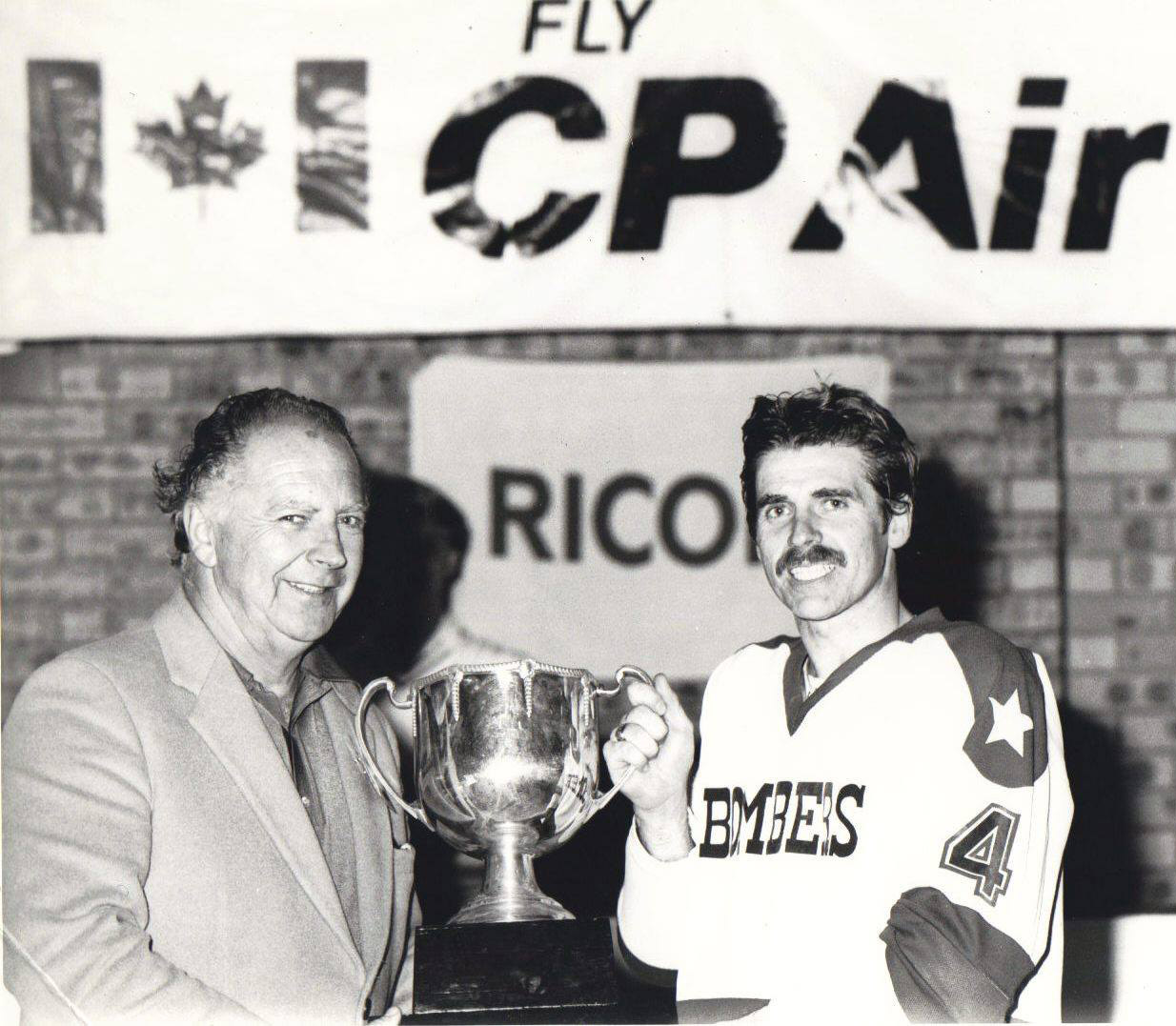

On left with Allan Harvey, Warringah Bombers, last National Ice Hockey League Champions, 1981. The photo was once on display in the Australian section of the International Ice Hockey Hall of Fame, Toronto. Courtesy Allan Harvey. [11]

On left with Allan Harvey, Warringah Bombers, last National Ice Hockey League Champions, 1981. The photo was once on display in the Australian section of the International Ice Hockey Hall of Fame, Toronto. Courtesy Allan Harvey. [11]

UNOPPOSED BY SIX NATIONAL PRESIDENTS, the dream of a national ice hockey league had only ever raised concerns over how to fund it, and Phil Ginsberg arrived in the top job at the national association at the start of its second season. Just in time to help the rink operator's association, led by Pat Burley who initiated the League, at the very moment they sought greater involvement of the sport's controlling authorities.

His administration included Sandi Logan (secretary), Charlie Grandy (vice president), Elgin Luke (coaching director), Terry Mouland (treasurer) and Paul Chartrand (referee-in-chief). Sid Neate handled the sports medicine and former Brandon University Bobcat, Mike Johnston, assisted Luke.

But the league floundered in that second season when refereeing problems emerged, sponsorship and promotion proved insufficient to cover expenses, and the spectator capacities of some rinks were inadequate to generate enough revenue. In other words, the long-standing concerns on how to fund it proved to be well-founded, and the new administration was also pressured to act on the displacement of many local players by overseas players in some NIHL teams. As strange as it seems, one was the cause, and the other was the effect.

Ginsberg withdrew support for the League, announcing the national association would focus on juniors in 1982, but would not stand in the way of those who wanted to pursue it commercially. "As an amateur organisation, and as a member of the Australian Olympic Council," he said, "it is our mandate to develop the up-and-coming Australian boys". It was a decision that disappointed many.

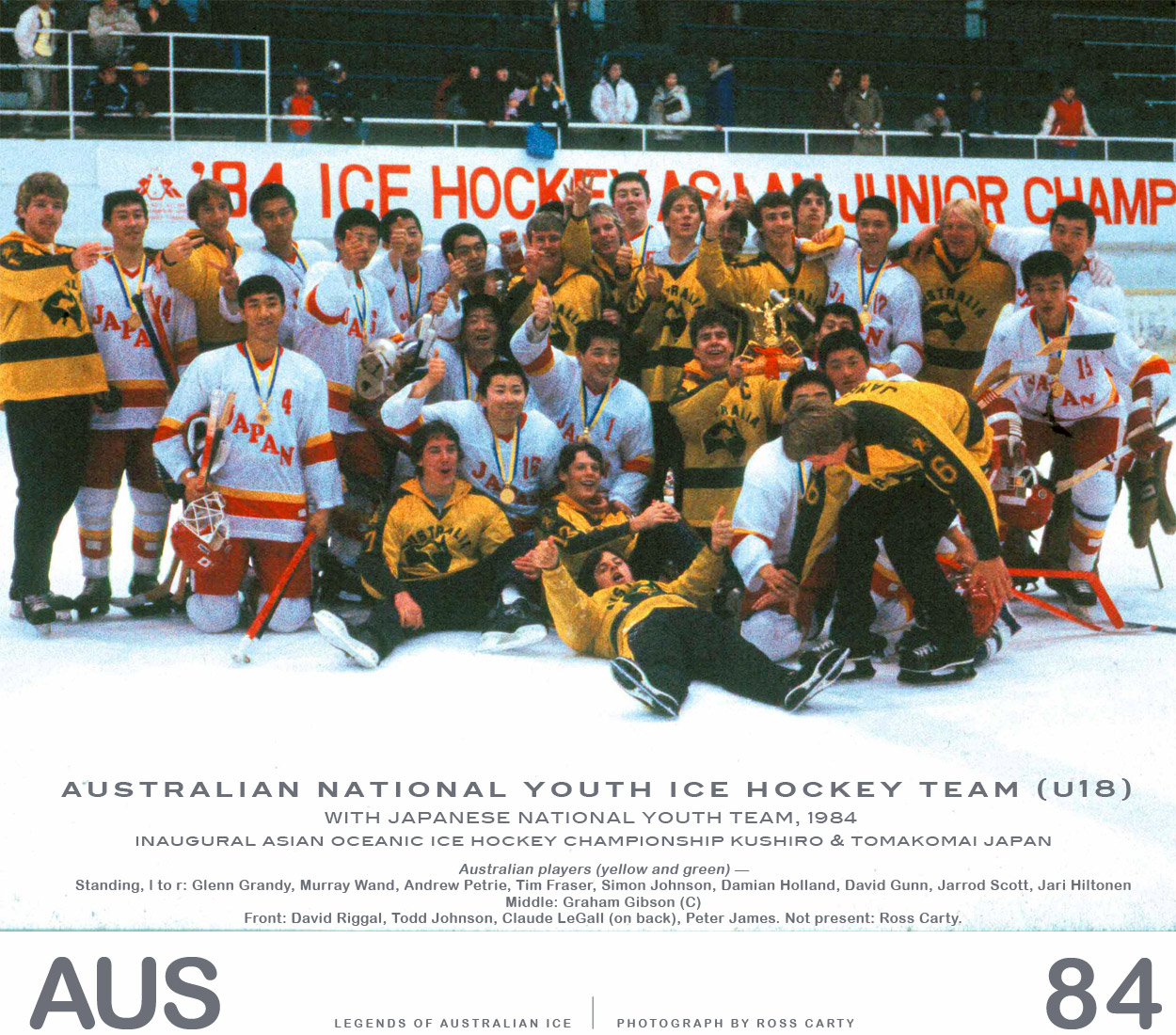

Instead he gave the country's winter sports and Australian Olympic Federation an undertaking to develop young active Australians into world ice hockey competitors. By select recruitment of some of Canada's and Europe's best coaches, he was able to give Australians "the first opportunity to be coached by the best". Ginsberg lobbied the IIHF to conduct an Asian Oceanic series for member countries liike Japan, China, South Korea, Singapore, and North Korea.

And it paid off, with the creation of Australia's first under-21 and under-19 international squads and, later in the early-1990s, the best ever results by a senior squad under Coach Ryan Switzer.

"Australia is on the right track towards an ice hockey identity of its own," said IIHF vice-president Miro Subrt who attended the series. "And we are proud of the work of Mr Ginsberg and his Federation". The long term plans of the administration included re-entry to the Olympics in 1988, almost a quarter-century after falling to Japan in the 1964 Olympic Playoffs in Tokyo.

If someone said the growth of Australian ice sports is limited by a shortage of ice rinks you might agree. But what would you say if someone said the number of ice rinks is limited by the economic growth of Australian ice sports?

Historically, private rinks here are not like Council swimming pools or football ovals. Ice rinks are businesses operating in a competitive market place with comparatively small demand for their services. Expensive to build and run, usually without government subsidy, they can make a profit, but they often struggle just to cover costs. Year after year, they must generate enough revenue from organised sport and recreation to cover costs, or run at a loss. How much depends on the debt they service, and the efficiency of their annual operating, maintenance and replacement costs.

For a new rink to happen, there must first be a demand for the market to supply it, and some degree of investor confidence in both the short and long-term. Demand comes from active and inactive participants in recreational and competition ice sports. Inactive participants are friends, family and supporters. Prospective investors look at how their competitors are doing and make a prediction on how they might also do, usually in a market catchment where there is no rink. If the demand nearby is not there—the stands half-full, the rink half-used—they probably won't bother. Because they just don't know if they can pay the bills.

Most active participants in ice sports the world over are locals, unless they belong to a sport that is over-reliant on imported overseas participants. In that case a lot, and sometimes most, come from overseas. Some people think that is fine, because they assume overseas players will bring knowledge, skill and experience greater than the local system produces, which they want to see. They think it will be good for their enjoyment of the sport.

But historically each new import further diminishes local participation because the amount of ice time here is finite. The market doesn't supply more ice rinks for overseas players because they contract to play a fixture at existing ice rinks for existing clubs. Instead, imports displace some competition-calibre locals, relegate them lower to non-commercial leagues where demand for ice rinks is weak. Some are lost from ice sports altogether. So too are the inactive but revenue-generating participants around them—their family, friends, and others who support them.

"Oh well, they're not good enough," say the group of fans, media and others who aspire to the higher standard of ice hockey overseas. And that's a problem, because it's the active local participant in ice sports who generate ice rink revenue by paying to play and by bringing inactive participants to the sport (patrons, sponsors). And there are plenty who are potentially good enough—if we count the ones who fall by the wayside.

Over a lifetime, the revenue potential of a local might be as low as a few people attending games per participant (eg., friends and family), rising to as high as 100 or more with skill development (eg., national league or team tournaments). But this reduces when their potential is not realised and they are lost from a higher league. And, of course, they generate no more revenue at all when they are lost from the sport.

But, wait. If semi-professional clubs use lots of imports, they must potentially generate the same or more revenue, right? That might be the case for a Wayne Gretzky, but the reverse is true for the typical player attracted here in their overseas off-season. Don't they draw more fans to the game? Sometimes, but never enough to compensate for the resultant loss of revenue. Don't they help train young locals, coach local teams? Some do, but so do many local participants, and at entry-level it's a task skilled locals can do equally well.

That's why some people talk about good and bad imports. By good they mean those who are both capable and interested in developing Australian ice sports through local participants. For example, most ice hockey imports are here for a tiny fraction of the lifetimes of locals, and at a cost to the sport, because clubs at least pay for them to play, along with their travel costs, upkeep and whatever else they negotiate. But it comes at a cost: the potential revenue from the local the import replaces. Sitting displaced players on the bench to try to keep that revenue does not work because players pay to play, and why pay for nothing?

Importing overseas participants adversely effects revenue in two ways, a double debit, and that in turn raises questions about ice sports' capability to self-regulate in a risky market. Losing local participants is the same as losing revenue, and that increases investment risk. Loss of revenue and increased risk affects demand for ice rinks. It's not a win-win situation at all. The sensible way is to import only in moderation, and only strategically—bring in overseas players who directly develop the local game. But try telling that to a coach who wants to win the trophy. Or a GM short on local players. Or a fan of overseas pro leagues.

For these reasons, the highest and best use of an ice rink is a full calendar of active local participants every year, which is physically possible, appropriately supported, financially feasible, and which results in the highest value.

Local participants have the potential to generate revenue for ice sports over their whole lifetime. From the time they step on the ice as a youngster or teen, to the time they stop supporting the game which, for many, is often long after they become inactive. A national league participant generates thousands and thousands of dollars of revenue every year, and if they play on a national team, they give thousands more to help raise the sport's profile.

But locals also generate at least a thousand or two here every year just to get there. They pay to play in local clubs and in interstate tournaments, they buy gear, they use gyms, they attend events to help fundraise. It might take 10 years, and after they retire from competition many go on to spend thousands more in local and old-timer leagues.

The real value to the sport of a lifetime local participant is hundreds of thousands of dollars, compared to the negative revenue value to the sport of an imported overseas player. Even if an import stays, he or she does not have the potential to generate the revenue that a local does. They spent a large part of their revenue potential overseas, not here, in return for a higher level of skill development and opportunity that is not available here. Unless they were imported very young, in which case, they are locals.

A fundamental injustice seems to live in this system, and from time to time it seems to flare up and spread like a cancer. It benefits those who did not build the sport here at a cost to those who did. And it's a hard pill to swallow, especially when the sport raises on a pedestal those players who spent many years out of the country in better hockey schools and leagues, then returned to play in leagues financed by those who stayed. Built by those who paid to play here, those who generated the revenue for the rinks here, who paid the cost of representing their country here.

The vast majority of locals are not paid to play or given incentives like some of those who went overseas and returned. They are not fawned over by coaches, fans and media. They are often sidelined for being comparatively less-developed, even when they show great potential. Locally developed players have often been excluded from their National League or National Teams, often by overseas-born coaches, in favour of players with skills and experience gained in overseas development leagues that were not open to most Australians.

Our system of privately run ice sports requires business acumen to monetize potential revenue, to structure it commercially into something approximating a piece of pie, and not just a plate of crumbs. A healthy integrated organisation, not a cluster of disintegrated and disorganised clubs, incapable of generating a sporting spectacle that people want to see. At least part of the income from that kind of organisation could be reinvested back into the sports and infrastructure for greater return. Until, eventually, Australian ice sports become a self-sustaining critical mass. A real piece of the pie.

In the meantime, it makes no economic sense to displace a lot of Australians from their ice sports by importing and naturalizing overseas participants. They just don't generate enough revenue in their own right to compensate for the loss of local participants. That means they also have an adverse effect on the supply of rinks.

The worst kind of displacement is a young local participant replaced by an older overseas one, because youth has the greatest revenue potential. Historically, coaches and administrators who don't think this way, have always been a liability in Australian ice sports, because they cut the potential revenue needed to keep up existing ice rinks. They also cut the demand for new ones.

There is an unwelcome implication in this. Ice hockey clubs that can't sustain a competitive roster of 22 local participants to play three 20-minute periods in a 28-round national league fixture, are not yet at national league level. Because it is more economic to not permit, or at least limit, the use of overseas players to make up a shortage.

In one very important way, the competition model of Australian ice sports is their own worst enemy, because the short-term thinking of win-at-all-costs can replace a winning culture that develops over whole life-times. And even if nothing else is clear, it should be obvious that ice rinks are long-term financial speculations that require long-term revenue streams. Fortunately, so are many participants, from atoms all the way up to old-timers.

Coaches like top imports. Fans like top imports. But some top local players believe they learn less from imported players, and more from national or overseas programs, or even imported coaches. Many also struggle for the ice time that is essential to realising their growth and development potential.

Some imported overseas players can improve league quality... Arto Malste, Darrell Becker, David Turik... and so a few of the best available might be justifiable. But local experience shows that does not translate into increased revenue, nor more ice rinks. This is partly because imported players consume revenue and other resources, while displacing the revenue local players always bring to the game, along with all those other participants orbiting around them. But it is also because many imports don't think long-term. They're not focused on helping to build national ice sports. So their clubs and media build them up into something else.

In Western economic theory, it is now believed imported products are good because they allow a country to concentrate on what they are good at, thus creating jobs: supply creates demand. And it's usually true when an economy is good, there is an excess demand for goods, so of course imports rise, as does the number of jobs.

But these theories do not describe the behaviour of the current economic structure of local Australian ice sports, and it is doubtful they ever did. Local clubs generate enough revenue to pay for importing overseas players, and they take jobs here. But that doesn't create opportunities for local participants to concentrate on what they are good at. It diminishes opportunities. Why?

Let's reframe the question. Who will build a rink in the tiny Australian ice sports market for a league of overseas players? History has shown the answers to that question are too few and not in a sustainable way, or no-one here. The reasons? All the above. Pat Burley tried.

Anything like that here only survived on the back of local participants, including natural migrants, not imported participants. Because the two types are mutually exclusive market segments, shamateur vs amateur, and one usually gets hurt when they compete for the same limited resources in the same structure. This impact on growth is only reduced when long-term goals are aligned and enforced.

Unlike the demand relationship, the supply relationship is a factor of time. Suppliers meet a sudden increase in demand for say, umbrellas, in an unexpected rainy season by using their production equipment more intensively. But, if there is a climate change and people needed umbrellas year round, suppliers have to change their equipment and production facilities to meet the long-term levels of demand. People won't supply more rinks for a sudden increase in demand. If they tried, the rinks would be in low-cost tin sheds, not fit for purpose. But investors might supply more rinks if the demand is expected to be long-term.

The world's top professional league does not have this problem because it has its pick of players from the top leagues all over the world. They are able to generate enough revenue to make it work—often without even paying towards the cost of player development. An NHL style league set up here, similarly capable of paying its way, would supply its own rinks, players, and everything else it needed. It would probably have less impact on the local ice sports economy than the current national league.

Historically, the supply of ice rinks here is better correlated to the supply of young local participants, and that requires long-term thinking, lifetime thinking. Ice sports shoot themselves in the foot when they interrupt that supply for a short-term gain. Something always comes crashing down. Four imports not enough? Naturalize them and get four more. Keep going until locally born and developed players are a small fraction of the team. In recent times, there have been more overseas born and developed players than locals in most clubs of the national ice hockey league. This is not the big-time NHL, and clubs ignore the effect that has on the local ice sports economy at their own peril.

Even when clubs win the trophy like that, they lose the greater game. This is what was happening when Phil Ginsberg took over in the early 1980s and promised the IIHF and the Australian Olympic movement something better. The best things organizers can do to increase demand for ice rinks are: (1) use the revenue potential in the number of participating locals; (2) use the revenue potential in the whole lifetime participant; and (3) draw new locals to take part in ice sports.

For example, today the IIHF junior men's competition is its biggest revenue generator. Monetizing the revenue potential of the national junior league by integrating it with the clubs of the national senior league could better use: (1) the number of participating locals; and (2) the whole lifetime participant. The revenue potential of clubs would increase, allowing them to move closer to a sustainable critical mass. They have more of the lifetime player.

Improved development pathways are likely because national league clubs then have revenue incentives to develop their own junior players. Reciprocally, junior league clubs benefit from more experienced national senior league clubs in running a commercial league. A few strategic imports might help improve junior league quality, and so on. This is a different way of looking at national league expansion, better suited to the realities of the Australian game.

Australian ice sports have done better at this in the past, and ice hockey played a significant role. So it should, because it has more participants than other ice sports. The juniors developed in the lead-up to the Ginsberg era, and during it, was one such occasion.

The administration increased revenues dramatically, perhaps the all-time high, introduced a national junior development system and national coaching directorate, restructured leagues, dramatically reduced the number of imported overseas players permitted in teams, worked with the IIHF to create regional competition for juniors, hosted their own international championships, and many other initiatives.

Some of the progress was marred by several bitter controversies arising from regressive policies or practices that discriminated against young female ice hockey players. Or discriminated against male players who were born overseas, but who were natural immigrants with legitimate entitlement to the same opportunities as locals.

The latter can be viewed as affirmative action promoting the group of home grown players who are known to have previously suffered from discrimination. "Phil Snr was certainly a man who saw a future for Australians playing hockey," notes former vice-captain of Australia, Allan Harvey, "not just imports playing hockey in Australia".

Local players are far, far more important than most organisers can comprehend. The principles underlying the progressive advances of this administration also explain other growth phases in the development of ice sports here, right back to how schools like Melbourne Grammar and their alumni associations established the sport here in the first place. Also why Oxford and Cambridge universities have the oldest ice hockey rivalry in the world. And, for that matter, the oldest Australian Rules football rivalry outside Australia. They don't import what they need to win. The supply of young participants is their business. And they built on that tradition.

Historically, the sport has achieved its best when athletes, officials and builders came together to collaborate on something new. A new spirit rising after the first world war produced one of the sport's most buoyant and successful decades, for men and women, for young and old.

The New Australians who arrived after the second war raised the bar even further, and then a new breed of rink operators redefined what was possible, enabling more people than ever before to play just for fun, while creating the necessary conditions for the nation to produce some of its best international results.

Yes, the sport has struggled for recognition, battled for resources, grappled with its own demons. But among the men and women who have shaped it, are many who made it their life, gave more than they took, and somehow found a way to work with others. They pushed the envelope, reached higher, and they also reached out, passing on life skills that motivated and influenced successive generations.

In a rapidly changing world, many good ideas fall between the cracks of history, and only rarely are we lucky enough to be able to revisit them. But the hallmarks of the highs of this sport were not just sporting prowess or sporting excellence. Not just scoring, preventing, or stopping goals.

They were new ideas, innovation and adaptation to the very things that disadvantaged us, but also made us unique. They turned disadvantage to advantage, gave soul to a new kind of team, even took ordinary kids from the streets and showed them a place they could become something good, or a place where they could simply just belong.

Australian ice hockey is at its very best when it becomes more than winning the trophy, more than the game. When the best people it produces share their skills, knowledge and experience to develop the whole lifetime player, the sport gives to the world something very special, something more important. A winning culture and camaraderie that is capable of inspiring whole lifetimes, whole nations.

Under Ginsberg's administration, the number of imports permitted in NSW Superleague teams dropped from 8 to 4 by 1984. The same quota has continued ever since in the national league, but there is still no quota on the number of naturalized players permitted.

"Mr Hockey" is inscribed on the gravestone for Phillip Raleigh Ginsberg at the Northern Suburbs Memorial Gardens and Crematorium, North Ryde, Sydney.

Special thanks to the young men of the first Australian National Junior Teams who helped record a piece of their story.

[1] Gravestones for Phillip Raleigh Ginsberg and son at the Northern Suburbs Memorial Gardens and Crematorium, North Ryde, Sydney.

[2] Legends of Australian Ice Facebook, October 2018. Comments by Sheila Ginsberg and Stephen Gibson.

[3] Come and join the team '84, program, Australian National Junior and Youth Ice Hockey, World Championships, Asian Championships, March 1984. Courtesy Darren Burgess.

[4] Legends of Australian Ice Facebook, February 2018. Comments by Michael King and Allan Harvey. For example, the vast majority of players on the 1987 National Senior Team for the inaural IIHF D-Pool Worlds hosted at home in Perth, were neither born nor developed in Australia. Similarly, the vast majority of overseas players on many of the Australian NIHL teams of the early 1980s were developed overseas and/or imported.

[5] The NSW Ice Hockey Association, facts and events, Syd Tange, 1999.

[6] Ginsberg's term is also notable for the new breed of coaches who were better educated for the task, and more interested in developing local hockey than importing ready-made players from hockey nations overseas. These included the spate of graduates from the Brandon University Bobcats; Jim Fuyarchuk who formulated the Under-18 National Youth Team program with John Botterill, and Ryan Switzer, whose Australian National Senior Team squads of the early 1990s produced Australia's best international results.