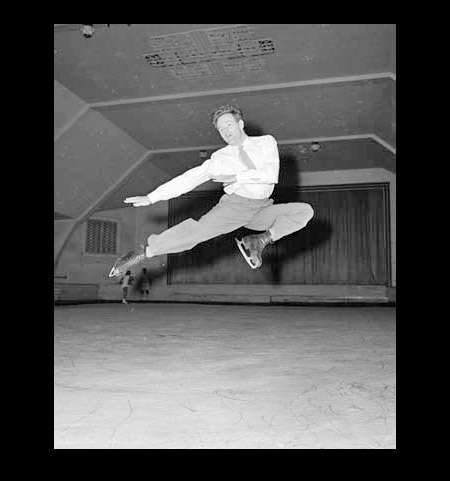

MOWBRAY PARK ICE RINK, EAST BRISBANE, QUEENSLAND, c1959

Brisvegas

The Messengers and the first ice rinks in Brisbane

Mowbray Park Picture Palace, 1931, site of Brisbane's first ice rink. State Library Queensland.

Mowbray Park Picture Palace, 1931, site of Brisbane's first ice rink. State Library Queensland.

THE BLUE MOON SKATING RINK is commemorated on a plaque under the Victoria rail bridge in Brisbane with other long-gone entertainment venues in the area. The roller-skating craze came to Queensland at least as far back as the late 1800s, closely linked to the same promoters in Sydney and Melbourne. These days the site is part of the South Bank promenade, but it was once a smelly, dingy and dangerous part of town with the fish markets on the other side of the bridge and adjacent wharves filling nearby pubs and streets with drunken wharfies.

Roller skaters could do artistic skating or speed titles and play roller polo against Brisbane, Rockhampton and Toowoomba teams. By 1954 roller polo teams such as the Blues, the Eagles, and the Avengers fought it out for the state premiership. The daughter of the General Manager, Ethel Flanagan, was Australian champion in 1938 and state champion for a decade. Yet, the Sunshine State was last to open an ice rink to the public, years after other states had celebrated a half-century of ice sports and closed.

The first ice surface for skating in Queensland came courtesy of Melbourne-born British theatre impresario Sir Oswald Stoll, the co-founder of Moss Empires in Britain. He converted the stage of His Majesty's Theatre in Brisbane for the touring English ice ballet Switzerland in 1939. Stoll was the first promoter to develop a stage ice floor at his London Coliseum. Five engineers, five miles of piping and five tons of plant accompanied the Switzerland ice show from England to Africa and Australia. It measured 12.2 by 18.3m (40 by 60ft). Of course, this was hardly a public rink, although the Olympian and world champion star of the show, Megan Taylor, used it to entertain socialites. Rink parties had become a fashionable preference over garden parties.

A syndicate announced the first purpose-built ice rink in the city the year before, and other paper projects followed. The proposed Ice Palais had an ice floor measuring 49.4 by 24.4m (162 by 80ft). Powered by a refrigeration plant from Trails Pty Ltd in Bridge Street, it seemed destined for a site occupied by a timber yard in Wickham St, Fortitude Valley, almost opposite the Municipal Baths. It did not open as expected in April 1939. It was moved to a council-owned wharf adjoining the Commercial Rowing Club boathouse at North Quay where it was to extend eight metres over the river. Instead, it quietly sank.

In 1947, Les Cecil, secretary of the state Pedal Cyclists Association, tried unsuccessfully to generate interest in an indoor cycling track close to the city, with a similar movable dance floor and ice rink. Brisbane suffered an appalling shortage of sporting facilities back then, and no one with money or power batted an eyelid.

Next up came Armand Perren, the world-renowned Swiss skater and producer-director of Ice Follie. His show opened in Adelaide in mid-1950, then Sydney, before morphing into Hot Ice at His Majesty's Brisbane in September 1953. Ice Follie broke the Brisbane theatre's long-distance run of 5.5 weeks previously held by Annie Get Your Gun.

Approached by local financiers, Perren became a technical adviser and board member of a syndicate intent on developing "the finest sporting stadium and ice rink in Australia, with a minimum seating capacity for 4000 people and an ice rink measuring 80ft by 180ft". They planned to equip the Olympic standard rink with a portable floor that could be installed over the ice in an hour for professional tennis matches, boxing, wrestling, vaudeville, dancing, or concerts.

"We do not intend to do things by halves," announced the former Matterhorn mountaineer. "The people who are financing this venture have great faith in the future of Brisbane. We will not spare expense". Victoria and New South Wales had two ice rinks apiece. Every state except Queensland had tried. Perren's Hot Ice toured Adelaide, Sydney and Melbourne, and his other shows followed in 1955, but the Brisbane rink proposal evaporated without the syndicate spending a penny.

In Perth and Hobart, speculative ice rink ventures with lower budgets than this had collapsed after their first few years. Sydney Glaciarium followed suit in 1956 after almost fifty years of operation, and Melbourne Glaciarium closed its doors the following year after a half-century. Australia lost four rinks in four capital cities that decade. Sydney had no ice until the open-air rink at Prince Alfred Park opened in 1959 along with yet another boutique rink, this time in Hindley Street, Adelaide.

Suburban cinemas struggled when audiences declined after television arrived in Brisbane in the late 1950s. Many closed with the buildings converted to alternative uses or redeveloped. Mowbray Park Picture Palace, opposite the Shaftson Hotel on Kangaroo Point, measured about 44m long by 26m wide, plus stage. It could fit an ice floor of one-half to two-thirds the minimum size of a competition ice hockey rink.

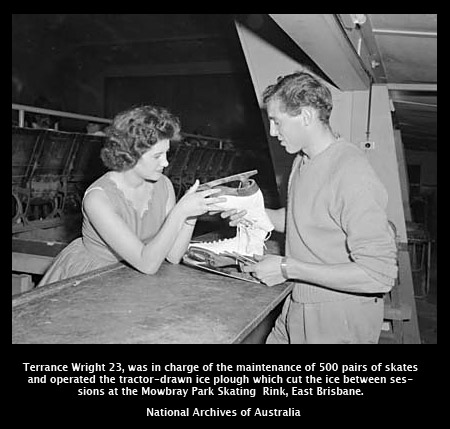

Mowbray Park Ice Rink, the first public ice rink in Queensland, opened in the converted picture theatre on the corner of Shafston Avenue and Wellington Road around 1957. In 1961, the rink owner announced he might sell up when Brisbane Mayor Clem Jones threatened to prosecute Sunday traders. But the rink continued despite a ban on commercialised Sunday sport. Brian Crossland and his wife Shirley managed it. Both were former members of the Blackpool Ice Dance Club at the Pleasure Beach Ice Drome in England. Terrance Wright maintained five hundred pairs of skates and levelled off the ice between sessions with a tractor-drawn ice plough. Originally from Farnborough in England, Wright was once chauffeur to the owner of the Streatham Ice Rink and cold stores in London. Marian Green, a professional acrobatic skater from the Blackpool ice revue company, also skated at Mowbray Park. She met her husband David Worrall at the Blackpool rink when he was the lighting director.

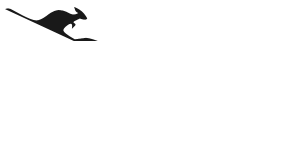

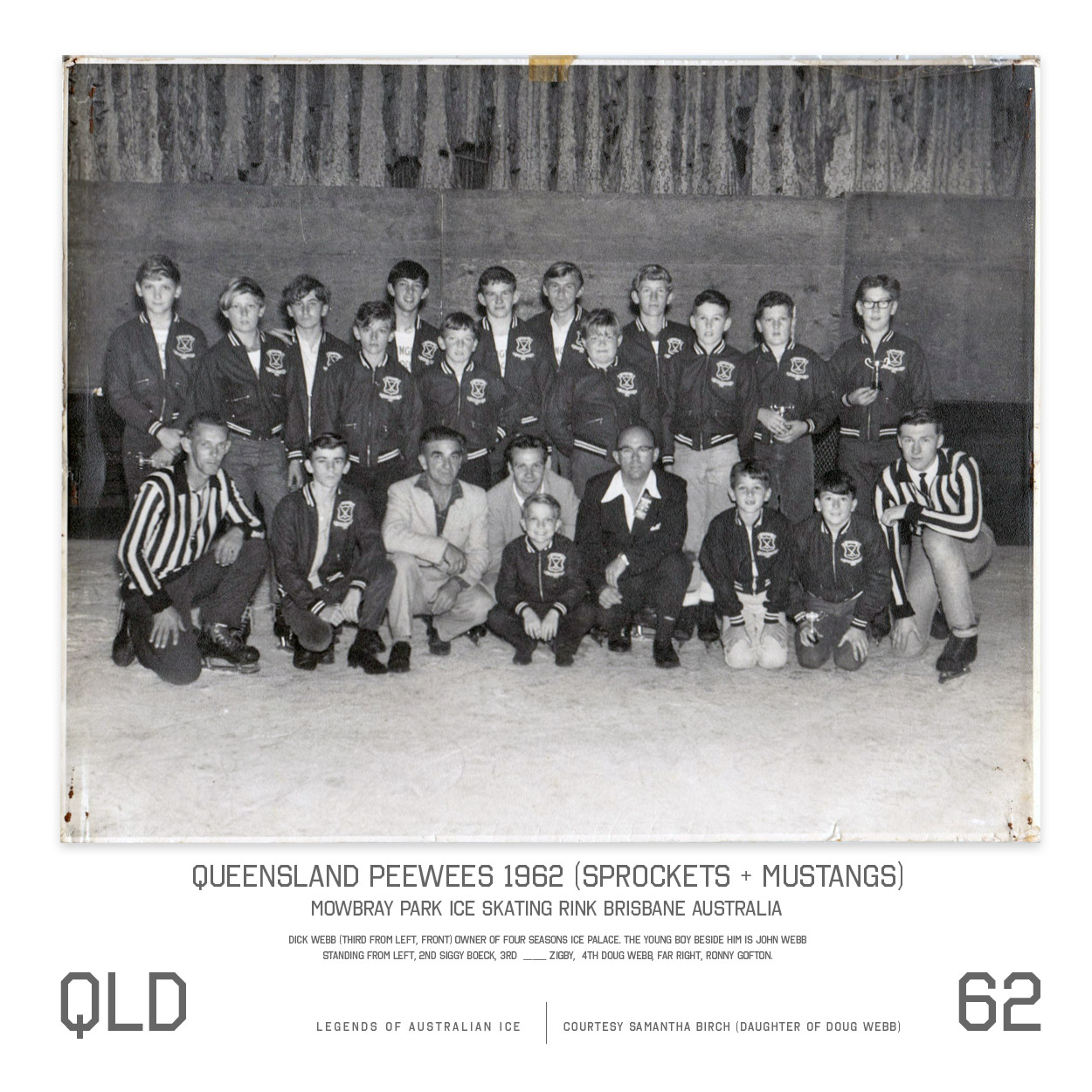

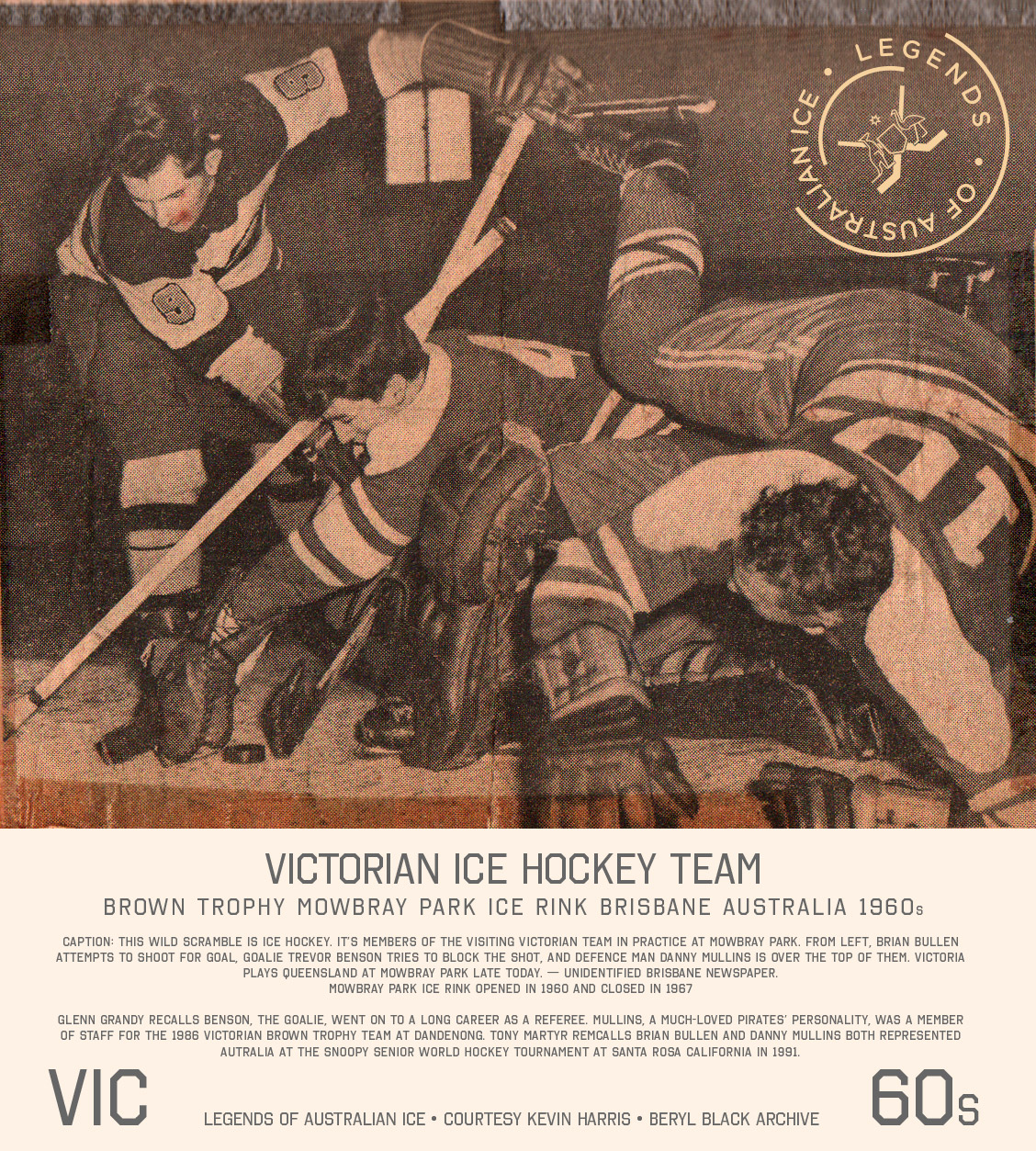

The thirty-four members registered to play ice hockey at Mowbray Park were quick to represent their state against scratch teams from visiting warships from North America. The number of player registrations in the state almost tripled over the next five years. Peewee and girls ice hockey teams competed from within a year or two of inception, and the take-up of the sport in the early years was strong and well-organised. The Queensland Girls Ice Hockey Association was formed in the mid-60s, perhaps the first in Australia. Eight women played a team from New South Wales in 1967. [3]

The owner passed the rink down to his son, Keith. It burned down in 1967 after nine or ten seasons, in which time the state set up its first ice hockey association and competed nationally in the Brown Trophy. "Queensland too is booming," wrote national ice hockey secretary Russ Carson in 1965. "The original capitation fees to Federation indicated a mere 34 members. This year the number of members participating has risen to 90". [1]

In 1971, Keith Messenger and Dick and Mavis Webb opened the new Four Seasons Ice Palace at Toombul in Brisbane. Four senior ice hockey teams started up—the Boomerangs, Redwings, Maple Leafs and the Blackhawks—and two junior squads competing for the Pennzoil trophy. Hockey and other ice sports expanded, mainly due to visiting Canadians.

The national association did not consider the state strong enough to compete in the Goodall Cup, the men's open competition. That could have been a miscalculation. Queensland reached the grand final of the national Under-23 competition for the Brown Trophy in 1972. The state won its first Brown Trophy in 1975 and, the following year, it earned the right to compete for the Goodall Cup.

In 1974, Wayne Raison became the first Queensland league player to represent Australia at the World Championships. He had started at Mowbray Park in 1962. Others followed, including David Lindsay, Kelly Armitage and Peter Nixon.

Queensland placed second to Victoria in the 1976 Goodall Cup. It was an outstanding feat. Hosted by Victoria in Melbourne, Robbie Stevenson captained the home side, a former top scorer for Britain. It included many other dominant players of the seventies—Jim Hannah, Sandy Gardner, Ian Holmes and James Christie with Charlie Grandy and Gary Croft in defense, and Barry Harkin in the net. Queensland also won the Brown Trophy back-to-back in Sydney that year (1975, 76) without most of its top under-23 players, who were with the senior team in Melbourne.

Seven of the Queensland Goodall Cup runners-up were selected for the Australian team to compete against the touring Olympia 80 team from West Germany at Iceland Ringwood the following June. Goalie Terry Mouland, Rick Schram, Thornton McLaren, Russ Trudeau, Paul Chartrand, Barry Norton and Jan Lindh. However, they did not compete in the mismanaged national tour. The team that met the West Germans in 1977 were all Victorians. But 1975 and 76 had signalled the shape of things to come from Queensland, two warning shots across the bows of the long-established senior states.

The following year, the Goodall Cup did not return to Melbourne or Sydney for the first time in its 68-year history. The banana-benders broke a sporting deadlock to become the first state after the two foundation states to win the coveted holy grail of Australian ice hockey. Led by player and coach Russ Trudeau and captain Thornton McLaren, Queensland won its first Goodall Cup in 1977 with 8 Australians in a line-up of 18. New South Wales had 5 from 15, and Victoria had at least 12 Australians from a squad of 17.

Doug Waymark, a Canadian, became the first Queensland league player to win the John Nicholas Trophy (Goodall Cup MVP). He played minor hockey in Burnaby, British Columbia, including Rep teams the last couple of years. Waymark came to Australia on a one-year working visa with three High School friends in October 76 and played for the Moreton Bay Sharks.

"Ice hockey is continuing to expand," wrote the host state in the championship program, "mainly because of visiting Canadians, many of them schoolteachers. While the local players have learnt a great deal from them, it must not be forgotten the future of ice hockey in Queensland rests with the development of the Juniors. In the coming season, it will be the aim of both the rink management and the Qld association to develop this facet of the game to the fullest".

There is no plaque for an ice skating rink in the graveyard of long-departed entertainments under the Victoria Bridge in Brisbane. Ice rinks and ice sports lived on. The early success of ice sports in Queensland would not have been possible without the pioneering work of the Messenger family and their helpers.

________________

Citations

1. Australian Ice Hockey Carnival 1965, program, NSW Ice Hockey and Sports Club Ltd, Sydney.

2. Special thanks to Gordon Lockyer who provided the address for the rink and detail on its demolition to make way for the road widening. Gordon played hockey there for the Redwings from 1960 and was one of the initiators of the Panthers IHC c 1963. Gordon's father worked on the refrigeration unit when it was previously truck-mounted for use in touring ice shows.

3. Goodall Cup Program, NSW Ice Hockey Association, Sydney, 1977. Queensland - Goodall Cup Champions, Four Seasons Ice Palace, Brisbane, October 1977. Courtesy Elgin Luke.

Four Seasons Ice Place, rear of building taken from south-west, Toombul, Brisbane, 1970s. Courtesy Peter Sagar via Peter Nixon.

ALL-TIME NATIONAL JUNIOR CHAMPIONS (YEAR BY AGE BAND)