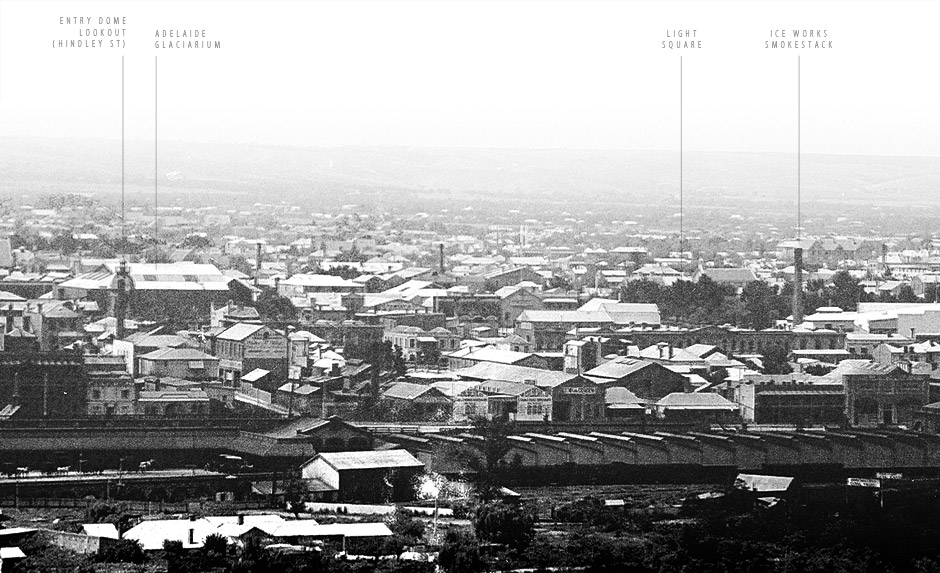

ADELAIDE FROM ST PETER'S CATHEDRAL SPIRE, c. 1906.Showing the Glaciarium Ice Palace behind Hindley St (now Adelaide Symphony Orchestra) and the ice works in Light Square (now TAFE). State Library of South Australia B 7761/3.

Napoleon's GhostAdelaide Glaciarium (1904 - 1908)

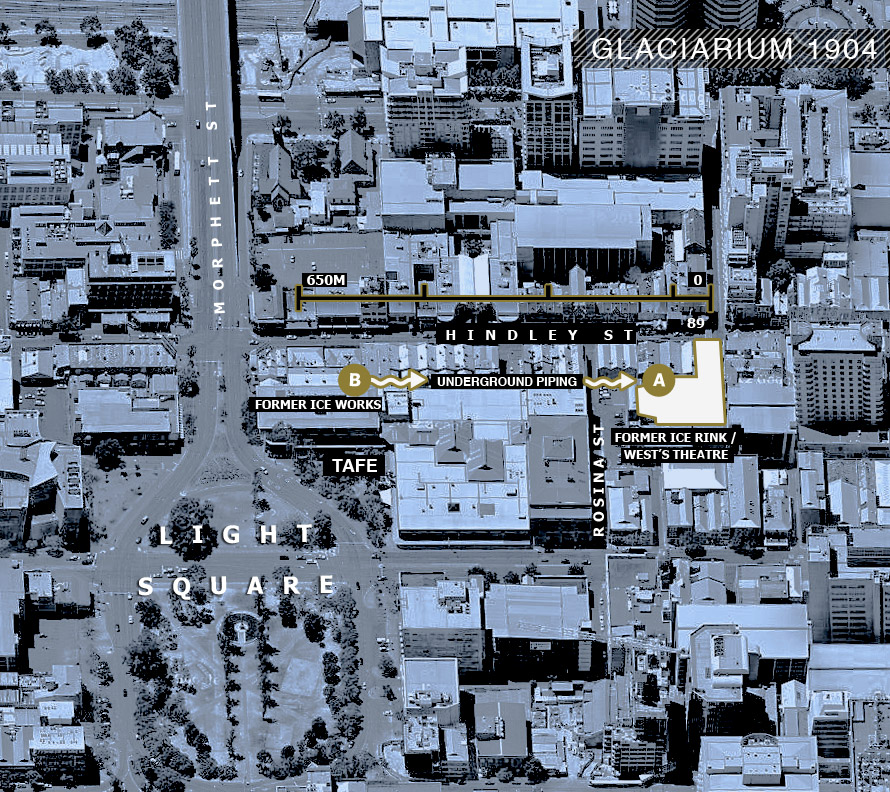

This was the first skating rink established on this side of the equator, and the only one in the world operated away from the base of its plant, the Glaciarium being 750-ft away from the engine, and the refrigeration absolutely traveling from the engine three-quarters of a mile before it returned to it, through the series of pipes. As distilled water was being used the ice was pure, and therefore of the very best quality. A number of American experts who have been here have declared it the finest ice floor they had ever seen... Mr Reid, Mr Stewart, Mr Booker and Mr Kennedy should be highly complimented on this undertaking, especially as other engineers in Adelaide had pooh-poohed the idea of the establishment of the rink, and expressed the opinion that it was impractical to maintain a sheet of ice at such a distance from the plant. To persevere with the construction of the rink in the face of such criticism required some pluck. Mr Reid's reputation was at stake in undertaking the work, and he was to be complimented on his success. [11]

— Dr Angus Johnson, Adelaide City Councillor and Chairman of the Adelaide Health Committee, May 1905. — The Battle of Waterloo Cyclorama in Belgium, near the city of Waterloo

— The Battle of Waterloo Cyclorama in Belgium, near the city of Waterloo

THE SNOW IN THE MOUNTAINS was melting and the first labour prime minister in the world had just resigned in Sydney before they came to understand the gravity of their situation. For over a year, the engineering elite of Adelaide had been telling the world that the Melbourne engineer, Reid, was wrong. They had huffed and puffed all manner of science. It could not be done they professed, it was not possible to freeze an ice floor located two hundred metres away in their humble, but professional, opinion. It was not possible to pipe iced gas to the former Adelaide cyclorama with the Hercules refrigerator located in Light Square. [1] Australia had no ice rink for good reason, they blustered. It was hot, they huffed. Bloody hot, they puffed.

H Newman Reid stood in the lofty hall gazing patiently at the alien grid of white piping, lost in thought. Specially strengthened, they could withstand 140 pounds of pressure per square inch. He looked away, squinted once, twice. When his vision cleared he returned his gaze and re-focused. The water around the pipes had indeed begun to cloud. Allowing himself only the briefest of smiles, he turned abrubtly on his heel toward the Ice Palace's only exit and Hindley Street. It would be some hours yet before brownish white bands about a metre wide appeared. [14] There was one thing his detractors had been right about. It had never been done. Until now.

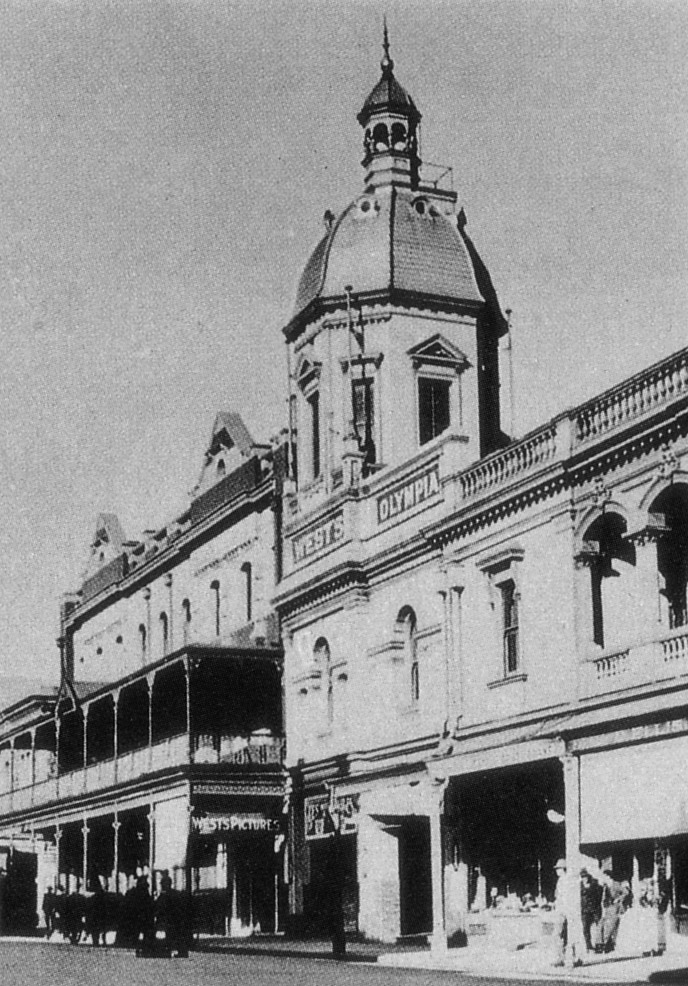

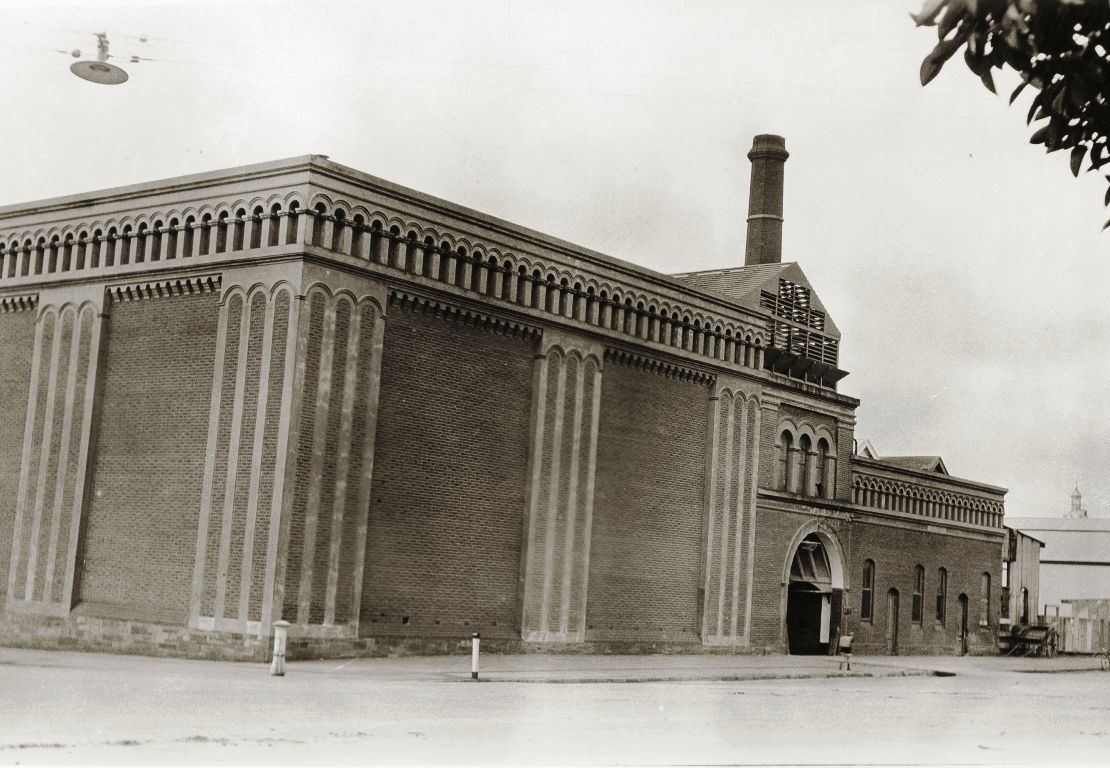

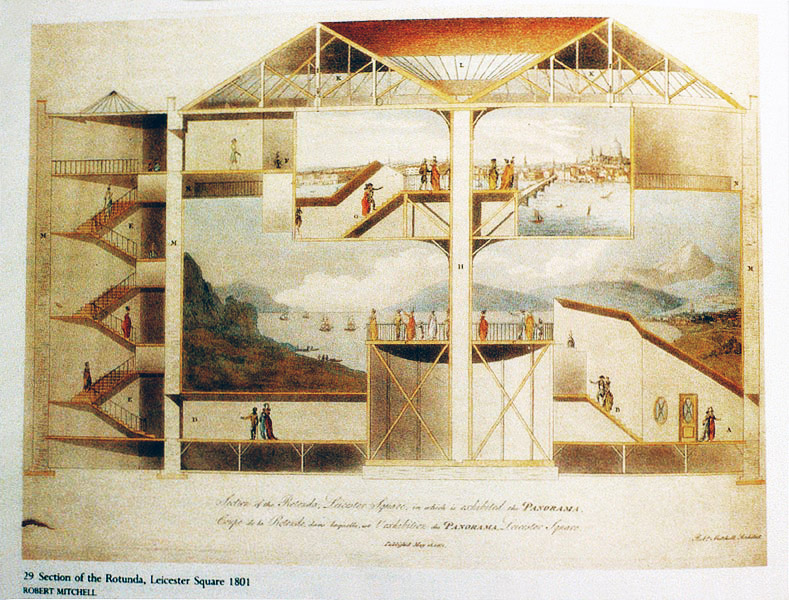

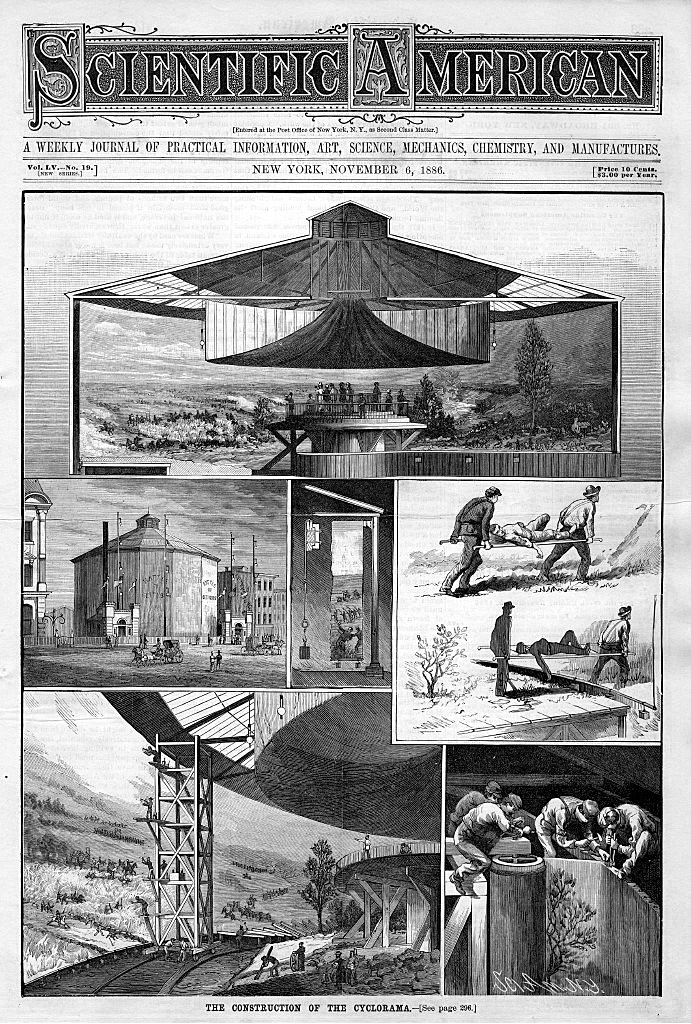

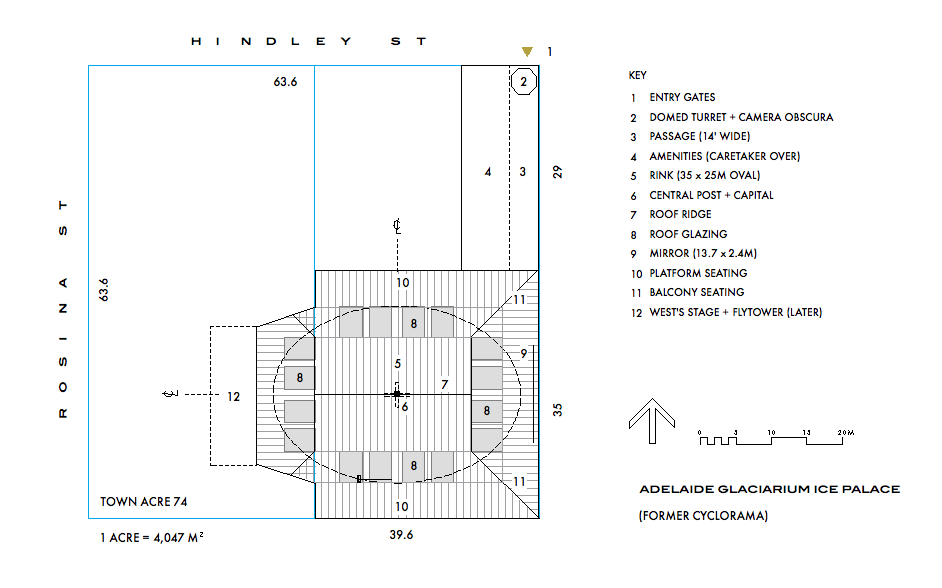

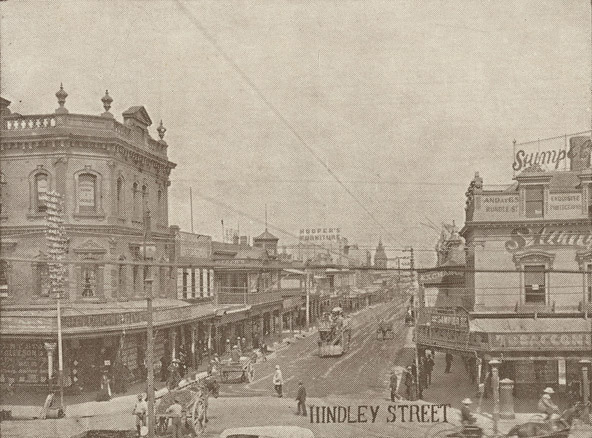

Australia's first ice rink was built in one of the most historic houses of entertainment in Adelaide. The cupolaed dome over the entry turret was as prominent on the low skyline then, as it was in the heyday of the cyclorama. Way back when the lookout was a landmark, a beacon, for the city's most exciting new entertainment, tens of thousands passed through its porticoed verandah into the darkness beneath the dome. Ascending a spiral stairway inside a dark passage, they stepped onto a big, slowly revolving platform at the centre of the main hall, [2] to stare in awe at an unbroken wall of beautifully lit illusionistic paintings. The cyclorama brilliantly turned epic battles and beautiful scenery into theatre-in-the-round. The Battle of Waterloo, valued by Customs at £20,000, was "the most expensive work of art that has ever crossed the Equator". [3]

Most cyclorama of the time measured 15.2 by 122m, almost as long as a football oval, and beautifully illuminated by indirect lighting from above. Broken gun carriages and other war relics in the foreground added to the illusion when the viewer stepped into the centre of the space. The ascent to the 15m diameter viewing gallery in Adelaide was five metres above ground. Signor Rago conducted an orchestra to heighten the effect whenever the lecturer, William Lockley, banged a small gong. The Waterloo exhibition ran for years creating new interest along the way with extra illusions and special effects, such as the enchanted "Fountain of Laughing Waters" with "its ever-changing and brilliantly illuminated waters". The appearance of Napoleon's ghost on the battlefield "mystified all those who have seen it". [5]

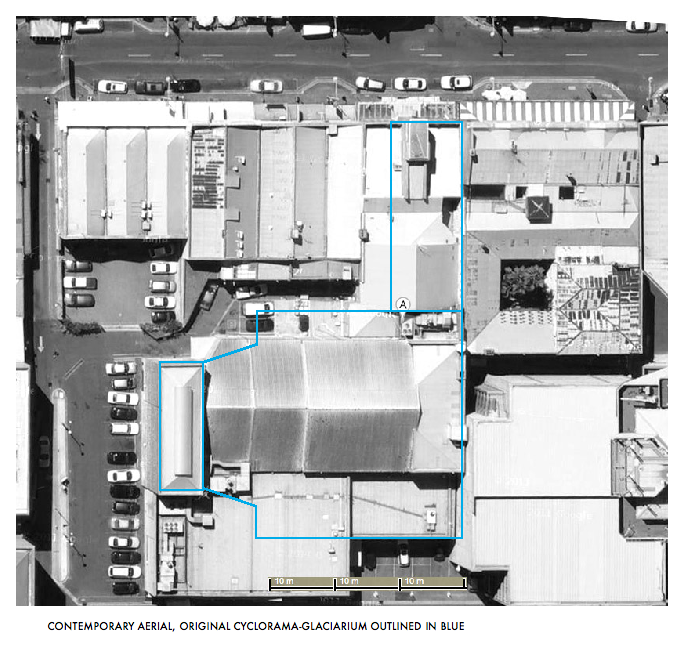

Local architects English and Soward designed the building for the Melbourne-based owner, William McLean, who leased it to the Adelaide Cyclorama Company. [18] In 1899, ten years after it had first opened, the building caught fire, destroying the cyclorama for both the Battle of Waterloo and the Battle of Crimea, along with most other contents. The solid brick walls were unaffected, and the roof and floor damage was at least repairable. Under-insured, the company voluntarily liquidated. In the hands of the bank, the building hosted prize-fights and the like until it was re-leased for five years to the Ice Palace Skating Company syndicate formed by Reid, with Sir Colin Stewart, chairman of directors of Adelaide Ice and Cold Storage Company (AISCC), and William Booker.

Although he was from Melbourne, Reid at that time was general manager of the AISCC ice works at Light Square for Sydney engineer, Charles Arthur Macdonald, who controlled the company. His chief engineer there, John Kennedy, was also from Melbourne, having emigrated from Kirkcaldy in 1886. [10] Macdonald was the owner of the Hercules Refrigerating Machine patents produced by the Hercules Iron Works in Chicago, and he had sold hundreds of the machines in Australia from 1895. By the turn of the century, it was said ninety per cent of the whole of the freezing machinery in Australasia consisted of the patent plants supplied by Macdonald's firm.

Comparable ice rinks in London, Pittsburg and Washington at that time had cost between £30,000 and £42,500 (about $4 to $6 million), but Reid's plan was to avoid the largest capital outlays on building and refrigeration plant, which also reduced ongoing running and replacement costs. He could do that by recycling the frozen gas byproduct from the freezing plant at Light Square, through miles of pipes in the ice floor, keeping it frozen for virtually nothing.

A rink like this could operate for under one-third of the cost of comparable overseas rinks with dedicated freezing plant. Reid's budget was no more than £5,000 (about $700,000) to cover the cost of repairs and interior decor, to prepare the floor, to provide an ice tank and piping, to light with electricity, to purchase skates, and to meet all initial expenses. [10] The syndicate went public to raise £7,500 ($1 million) capital, in 300 shares of £25 each.

The plan required pipes to be laid underground in public streets and lanes, and Reid had to abandon his first attempt in 1903, after encountering difficulties in obtaining certain rights-of-way along the pipe route. [4] The problems were overcome by June 1904, [4] and conversion of the cyclorama took only a further three months. Australia's first ice rink opened to the public on September 6th 1904. Skates were in short supply compared to demand after the public opening, but more arrived eleven days later.

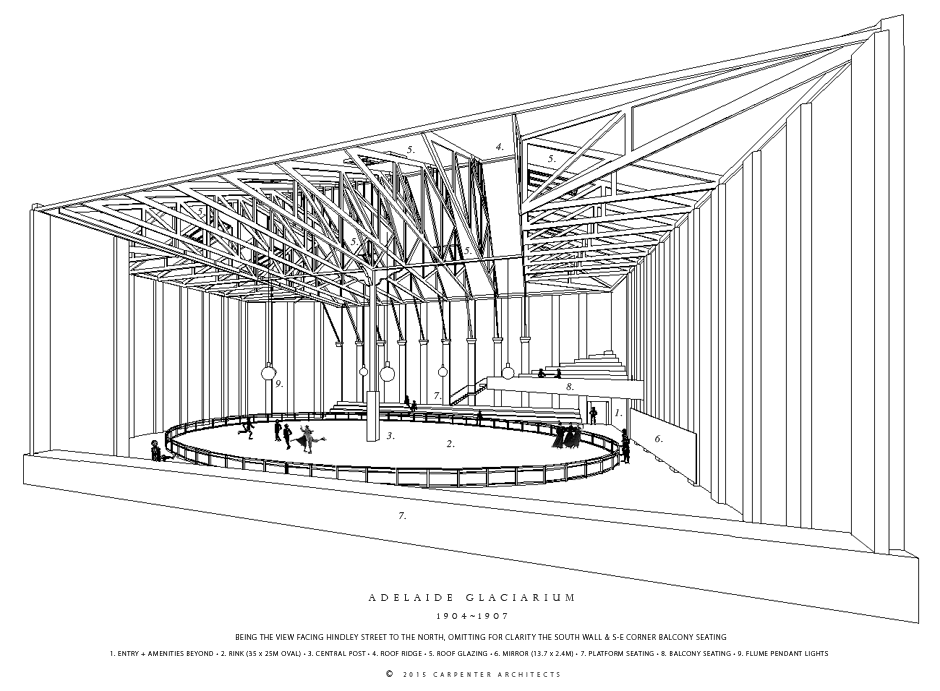

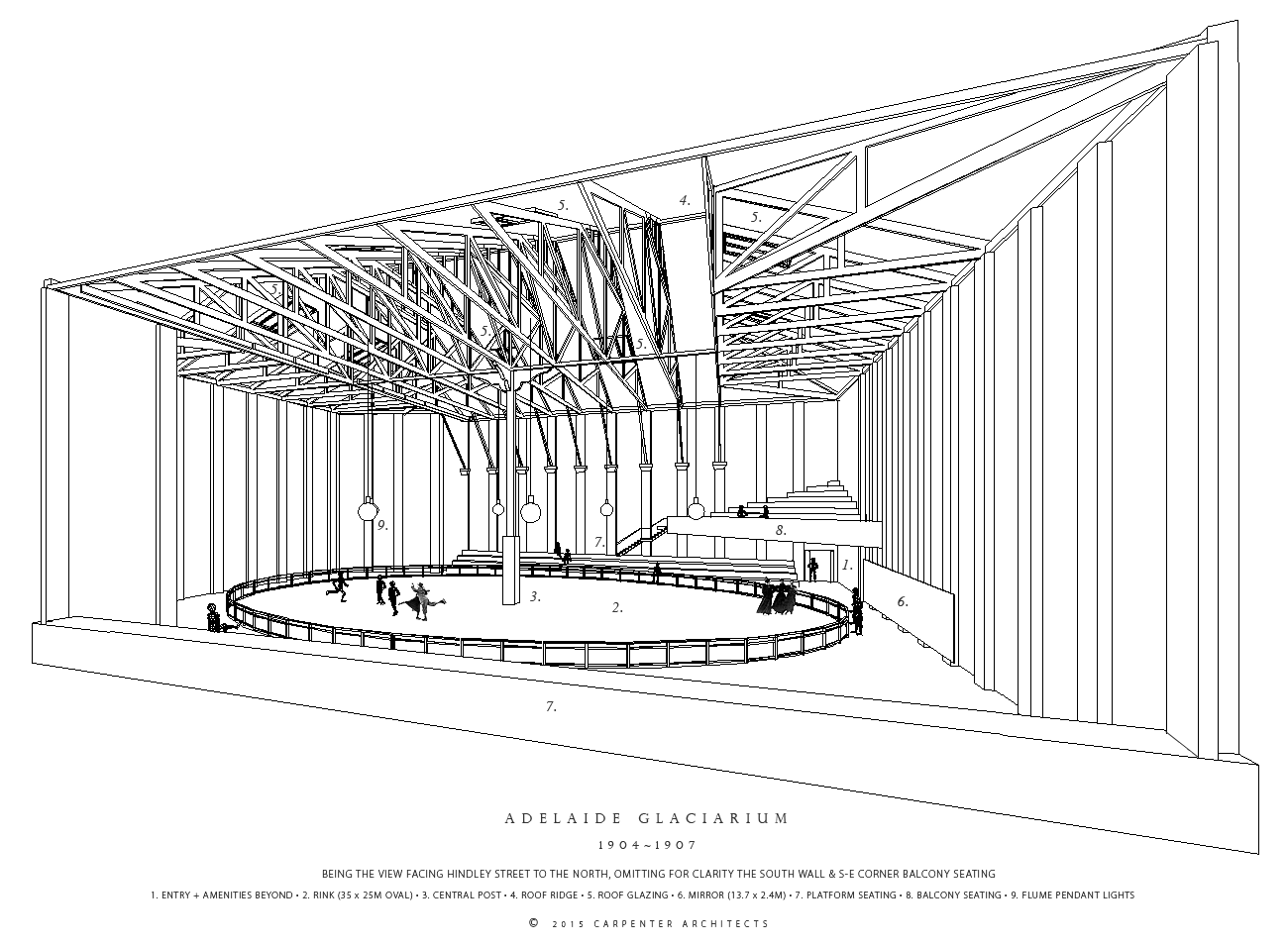

The main skating hall, the former cyclorama space, was 39.6 long by 35m wide and 14.3m to 15.2m high to the clear-span ceiling [4, 18] which, according to one historian, had a large glazed skylight located centrally. [15] However, the exposed trussed timber frame was originally "covered half with iron, and half with glass". [17, 18] By 1906, the area of roof glazing had reduced, but there were still multiple glazed skylights on each of the four faces of the Glaciarium's Dutch-gabled roof, as high above the ice as a four-storey building without the in-betweeen floors. The oval ice floor was 15cm thick and had maximum dimensions of 35 by 25.6m. That is an area of 685 square metres, although scaled drawings of the original layout based on the published dimensions suggest it may have been built even smaller. The minimum size for international hockey matches at that time was an uninterrupted oblong shape almost twice the length and surface area (54m by 23m or 1,242 square metres).

The column at centre ice was 0.9m square at the base, telescoping to about 0.4m square from a height of about 4m above the ice to the ceiling. A large mirror there was surrounded by upholstered seats on which skaters could rest. [7] This central area had also been used for a maypole, [6] and a bandstand for public skating sessions. A 1906 photo also shows it clear, two seasons on. Six pendant electric lights flooded the interior with 12,000 candlepower, and two more on the front wall lit the street outside. On the north and south sides of the lofty rink hall, spectators sat on platform benches trimmed with crimson velvet, and on the east was another larger mirror, 13.7 wide by 2.4m high. Elevated seating was constructed in the two corners on the east, beneath which a refreshment bar and a skate shop operated. Public change rooms, toilets, a smoker's lounge, and other facilities were located outside the main rink hall, off the entry passage in the double shopfront to Hindley St.

A form of bandy and field hockey was played there that year with a ball and field hockey sticks, and a form of roller polo, or polo on the ice, was played from 1905 with the shorter roller polo sticks and ball; sometimes even a football. Roller polo had been very popular in Australia since the 1880s. It was played by Professor Caldwell, in both Melbourne and Adelaide, before he became the first ice skating instructor in Australia. Claude Langley also played in these early matches in Adelaide, a few months prior to the opening of Melbourne Glaciarium, where he then became the first ice skating instructor with Professor Brewer of Princes and Niagara rinks in London. Brewer could turn somersaults while skating and he was also an accomplished speed skater who could complete six laps of the Adelaide rink (500m) in 1 min 2 sec. Half- and one-mile speed races had been common in Australian roller rinks for decades, and similar races were held on ice in Adelaide soon after the ice rink first opened.

Not surprisingly, the priorities of the first rink design were neither international skating competition, nor ice hockey. Australia's first ice pad was first and foremost an experiment, and more aptly described as an oval doughnut-shaped circuit. It was not that much more costly to replace the burnt-out roof with a clear-span like the original, but that was the least of Reid's concerns. There were other technical challenges in addition to those encountered in laying pipes in streets and laneways. Reid and his team were in unchartered and often hostile territory. Unlike most materials when they change state, ice expands, and keeping it within assigned limits was among the earliest problems Reid had to overcome. So too were impurities in Adelaide's water until Reid switched to forming the ice floor from distilled water. The ice quality had always been improving, and it was better than ever when the first full season commenced in March 1905, with the gated entry passage partitioned off from the rink hall. [10]

Reid redeployed the Adelaide experience in the design of the Melbourne rink and its basement ice works, the cradle of Australian ice hockey. He left Adelaide at the end of April 1906 to be General Manager of the Melbourne complex. The Hindley Street rink syndicate mutually agreed to dissolve their proprietors partnership, effective from the first day of October 1906. Colin Stewart carried on the business. [12] Macdonald sued Reid for alleged breach of agreement and won, claiming Reid was in his employ when he assisted in the promotion of the Melbourne Ice Skating Company and prepared plans and specifications. In 1907, the court ordered Reid to return 2,000 fully-paid-up shares in McDonald's company that were part of his remuneration, but he appealed the decision in the Supreme Court and won.

The instructors, Brewer and Caldwell, continued at Adelaide Glaciarium until it closed at the end of a shortened season in the Winter of 1907. Patronage had declined after Reid's departure, and the rink was converted to the Olympia Roller Rink and bicycle velodrome late that year; an asphalt floor operated by Horace Turner, manager of the South Yarra Roller Skating Rink in Melbourne. Professor Brewer transferred to Melbourne Glaciarium when it opened in June 1906. Claude Langley returned home to Melbourne, where he too became an ice skating instructor. John Caldwell remained and resumed roller skating exhibitions and instruction at the Academy of Music in Kensington Terrace at Norwood in Adelaide, when a roller rink was opened there in 1909. The Light Square ice works was taken over by the South Australian government in 1910, and renamed Metropolitan Ice Works.

And so it was, the forerunners of Australian figure skating, ice racing and ice hockey were established in Adelaide between March and April 1905, under the direction of an Australian champion roller skater, and a world-class ice skating instructor from London. Australia's first rink had operated successfully for the best part of three full seasons. The first organised ice hockey game in Australia took place at Melbourne Glaciarium on July 17th, 1906 between players from Melbourne and a visiting New York warship. This is the earliest known Australian record of a specific game of hockey in a specific place at a specific time, and with a recorded score, between two identified teams. The Victorian Ice Hockey Association formed there in 1908 and the National Ice Skating Association of Australia in 1911.

A certain generosity of spirit surrounded Reid and his enterprise; from the $10 entry fees, to the charity fundraisers, to the benefits for employees, to the quality of prizes at sports nights and costume carnivals, to the trophies donated to the ice polo tournaments of the traveling salesmen's association. He moved to Sydney after he lost a son on the battlefield during the Great War. His own private war to breathe life into ice sports was over then, although he still comes and goes from its battlefield, rather like Napoleon's ghost. Over the next few decades, the Academy of Skating on the banks of the Yarra River trained literally thousands of skaters, from novice to elite, and launched Australia onto the international winter sports stage.

Special thanks to Jason Sangwin, who has hunted down additional detail in his Adelaide Glaciarium Wikipedia article, and permitted us to use his wonderful interior photo of Reid's first Glaciarium when it was the Olympia roller rink.

[1] The Register, Adelaide, 5 Sep 1904, p 6.

[2] Chronicle, Adelaide, 27 Apr 1944, p 27. One of the Great Outbacks Revives Some Memories

[3] News, Adelaide, 1 Dec 1939, Once Scene of Cycloramas and Ice Skating

[4] The Advertiser, Adelaide, 3 Jun 1904, p 6

[5] South Australian Register, Adelaide, 5 Mar 1894, p 7

[6] The Advertiser, 2 Aug 1904, p 4

[7] The Advertiser, 7 Sep 1904, p 8

[8] The Advertiser, 9 Sep 1904, p 8

[9] Register, 30 Nov 1928, p 16. Obituary for John Kennedy

[10] The Advertiser, 3 Mar 1905 p8

[11] The Advertiser, 22 May 1905 p6

[12] The Advertiser, 26 Nov 1906, p 2

[13] Adelaide Advertiser, Tue 12 Mar 1907, p 8. Alleged Breach of Agreement

[14] The Advertiser, Adelaide, 17 Jun 1904, p 6.

[15] The Manning Index of South Australian History, Adelaide Cyclorama, Hindley St (1890-1899), State Library of South Australia

[17] Adelaide Panorama from Cathedral Spire, State Library of South Australia, B 7761/3

[18] South Australian Register, Adelaide, 20 Sep 1890, p 6

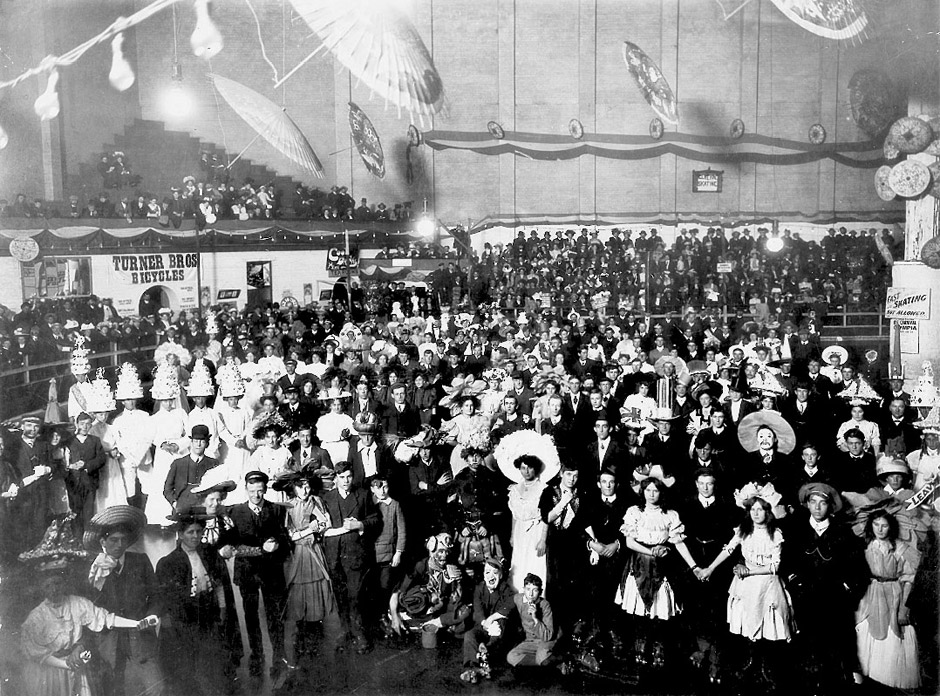

OLYMPIA ROLLER RINK c.1908, FORMERLY ADELAIDE GLACIARIUM. Future champions, the Beyer Sisters, are holding hands on the right. Image courtesy of Jason Sangwin.