THE YOUNG JOHN BOTTERILL IN THE HANDS OF THE GREAT GORDIE HOWE (1928-2016).Portage Collegiate auditorium, Portage la Prairie, Manitoba, Canada, late-1960s.

Windy Point

JOHN BOTTERILL AND THE POWER OF PERSPECTIVE

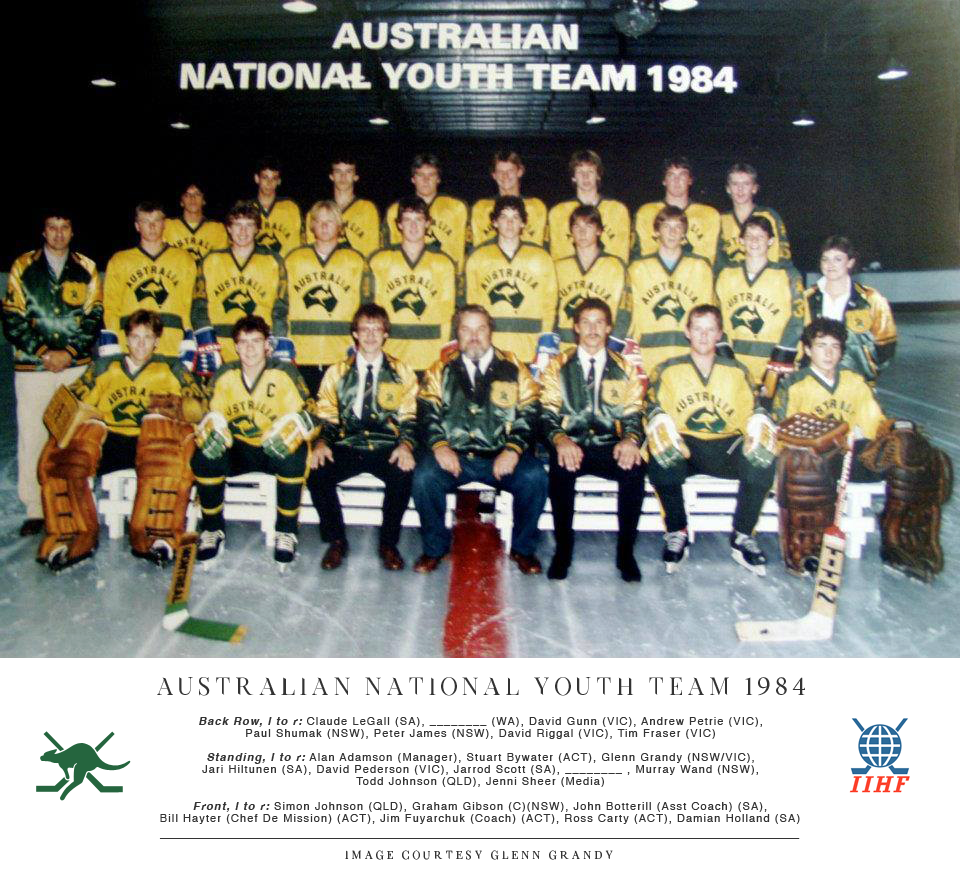

Australia has a lot of kids with great potential. If they work hard enough on their game Australia should have a crackerjack national team in three of four years. The lads seem terribly keen and I hope they get enough opportunities to improve themselves in the way of international competition. [6]

— Canadian coach Clare Drake, Australia, 1984. Clare helped coach the under-18 and under-20 Worlds teams Australia sent to Japan and Italy in March and April 1984. He was the most successful coach in the men's hockey history of Canadian Interuniversity Sport.

People with perspective know who they are. They benefit from knowing where their real friends are, and they know how they want to live and compete. [3]

— Dr Cal Botterill, Canadian sports psychologist, author and professor at the University of Winnipeg, 2005. His wife Doreen McCannell was an Olympic speed skater inducted into the Manitoba Sports Hall of Fame in 1995.

There is no doubt that Australian ice hockey, I believe, is in a strong position because of the hard work and commitment of so many passionate coaches and administrators over the years, who no doubt do it for the love of such a great game and definitely not for the money! ... Whatever we can aspire to and are able to attain, I do know from my 30-plus years of coaching in Australia that whatever the level, or whatever the ranking, our Australians will always take on the many challenges and compete with that "Aussie-Grit of Pride and Passion"! And all players, coaches, administrators and supporters should be — and always be — bloody proud! [4]

— John Botterill, former Coach of Australia's Youth, Junior and Senior Men's and Women's teams, 2016

— Coach Botts with the National Youth Team, South Korea, 1985

— Coach Botts with the National Youth Team, South Korea, 1985

THE INCOMPARABLE GORDIE HOWE reads your name out and raises an autographed Easton hockey stick. You kneel on one knee and wait to be touched on each shoulder, hoping he doesn't pull your ears. Blessed is he who has pleased the hockey Gods. You are fated for a career on the ice. Howe played hockey longer and better than just about anyone who ever laced up skates. In his NHL-record 26 seasons, he held the league records for most games played, most games with one team and plenty of the others until Gretzky broke some in the nineties. On this particular evening in the Portage Collegiate auditorium, five hundred hockey enthusiasts watched Howe present his autographed sticks to four boys, the smallest of whom lived in Oakville.

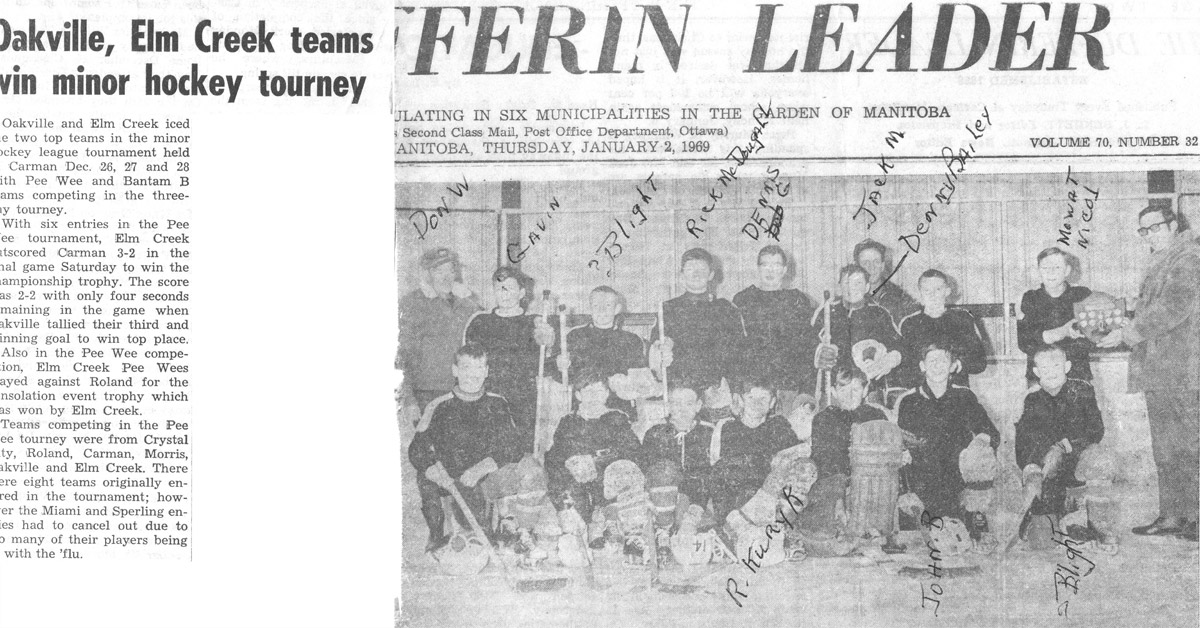

About a half-hour west of Winnipeg along the Trans-Canada Highway, and fifteen minutes before Portage la Prairie, Oakville is one of those small farming communities that have sprung up among the silent sentinels of grain elevators in the flat Prairie landscape. In winter, the Botterill family flooded a pasture beside their home for their own sheet of ice. The Oakville Community Arena that opened when young John was seven has been a fixture ever since, and home to legendary players such as NHLers Rick Blight and Arron Asham. Not too bad for a town of five hundred people. Hockey country.

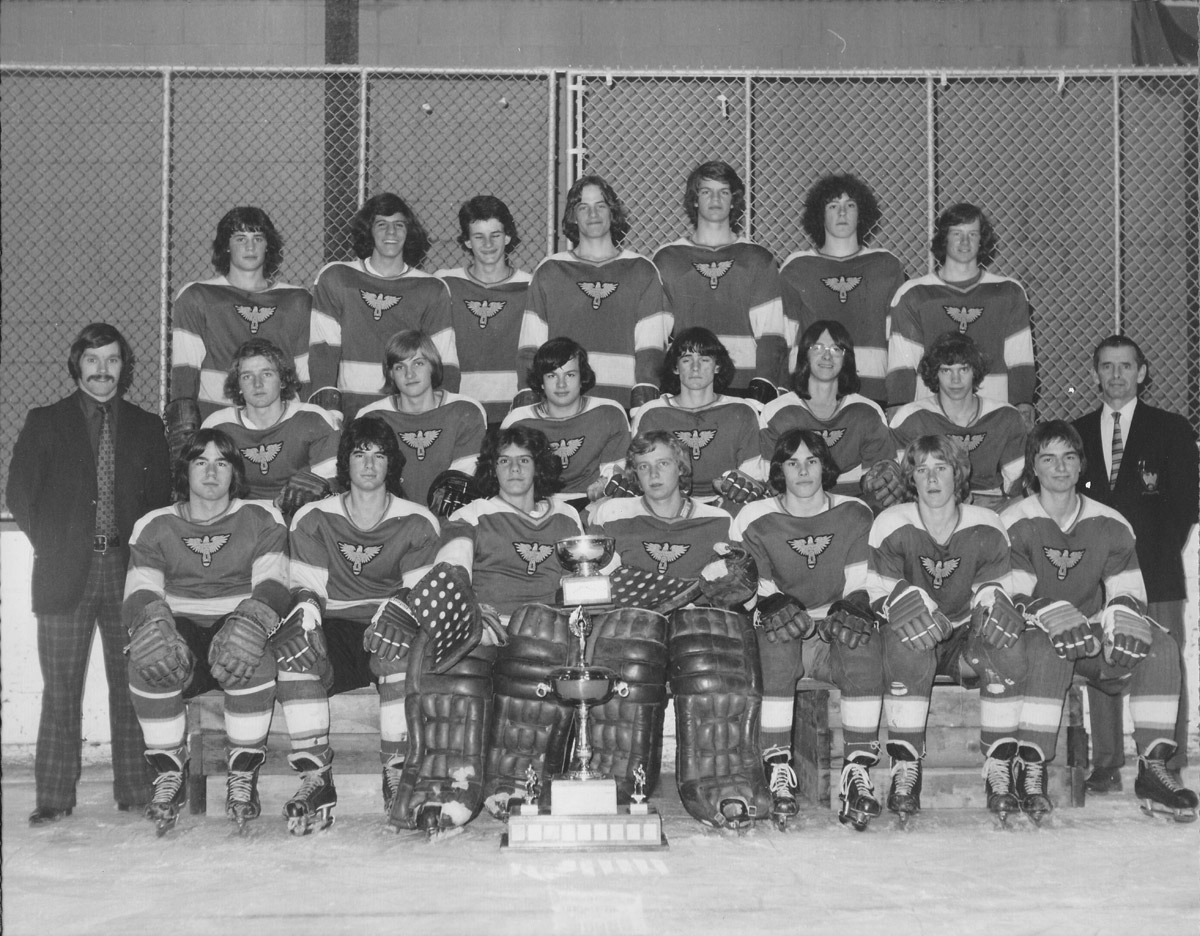

John Botterill began the game there in 1960 and played minor hockey to major junior and senior levels with his three brothers — Dan, Chris and Cal. Dan played local and went on to coach many seasons of the junior program in Calgary. Chris played some of the seasons during the Oakville Seals dynasty in the SEMHL. He also coached many years in local junior and high school programs, and championships with Arthur Meighen High School.

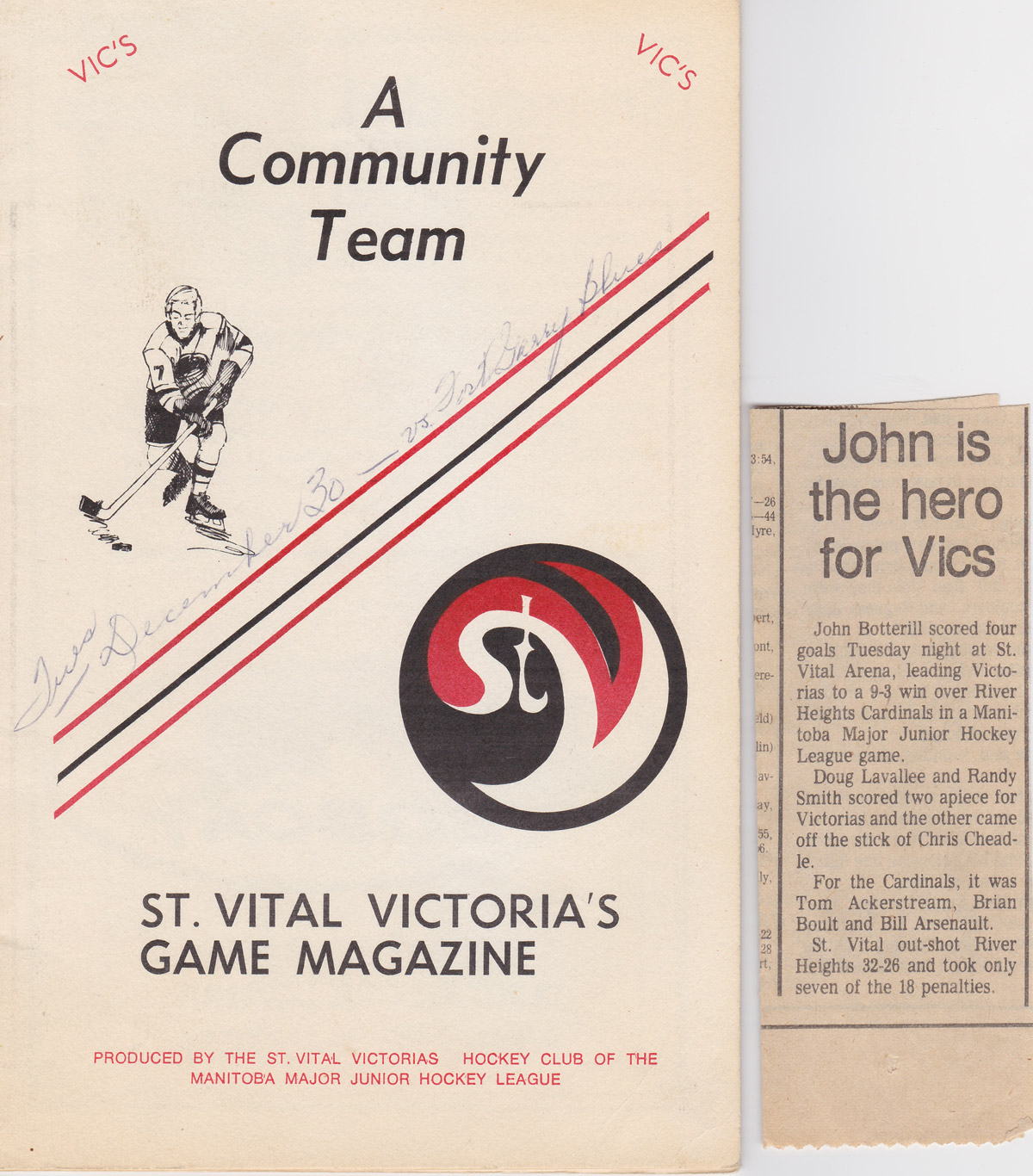

John was among the Oakville Pee Wee champions in 1969, then the Oakville Seals Bantam-Midgets in the years the Seals claimed five SEMHL championships (1968-1975). Their 84-26-8 record turned the Oakville Arena into a house of horrors for visitors. He also played in Portage, then Winnipeg including the St John's Ravenscourt high school team and the St Vital Victorias in the Manitoba Major Junior Hockey League. He played a little senior hockey in both Manitoba and Alberta while at University.

Born John Arthur Botterill on November 23rd 1956 at Portage la Prairie in Manitoba, his parents, Stanley and Ilene Alice, were recreational hockey players and skaters. His brothers were all older and so he was still in the process of becoming a Pee Wee Champion when Cal, nine years his senior, had already played semi-pro and made the Canada men's national ice hockey team three times, 1967 to 1969. Cal later worked as a sports psychology consultant and performance coach for numerous teams in the National Hockey League including, the Calgary Flames, Chicago Blackhawks, Los Angeles Kings, and Philadelphia Flyers.

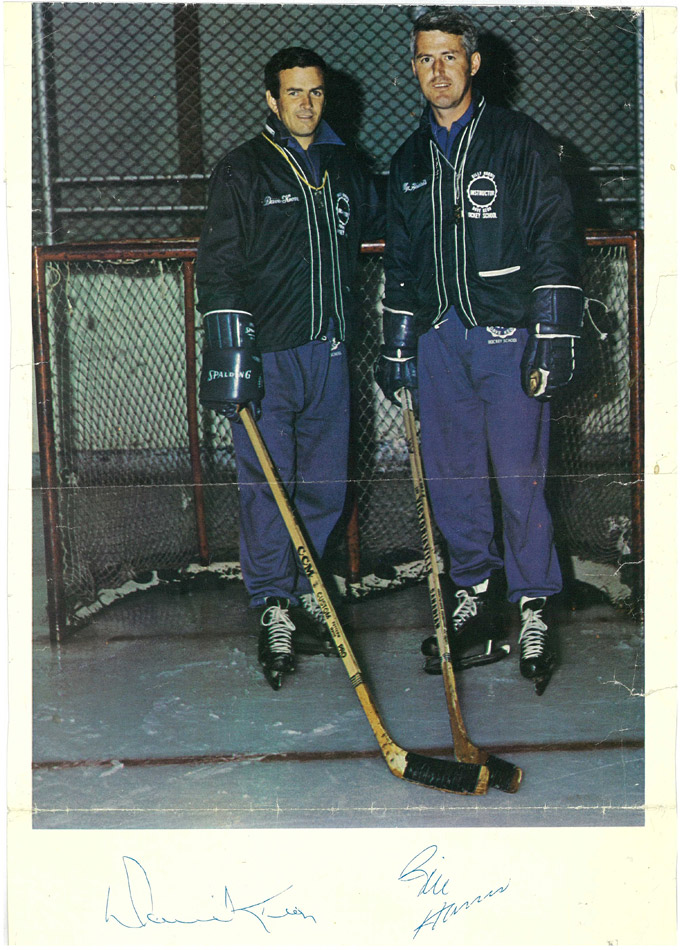

All three brothers were his mentors, along with the NHL's Dave Keon and Billy Harris, both of whom he met when he attended and worked as a puck boy at the Billy Harris - Dave Keon Hockey School at Dutton Memorial Arena in Winnipeg. And, of course, Gordie Howe who, on that fateful night in Portage Collegiate, had placed a big emphasis on his education and even suggested he should spend "four times as much time on books as on hockey". Damn. But perhaps that worked out happily because Botterill did graduate in phys ed from the University of Manitoba, later remarking, "If I had been in as good shape four years ago as I am now, I would have been able to make the University of Manitoba Varsity team. I was the last cut at the varsity camp, but I didn't look after myself". He continued on instead in the Winnipeg Junior Hockey League.

Botterill then decided to travel, arriving in Sydney Australia in January 1981 at the age of twenty-four, and touring through New South Wales, Melbourne and Victoria before ending-up in Adelaide. At that time, after the Dunstan Decade, the city of churches was home to almost a million people and regarded as less of a sleepy hollow than in the past. He was in the Barossa picking grapes with childhood friends Orville Hildenbrand and defenseman Richard Kuryk when he heard about the Adelaide Flyers of the inaugural National Ice Hockey League.

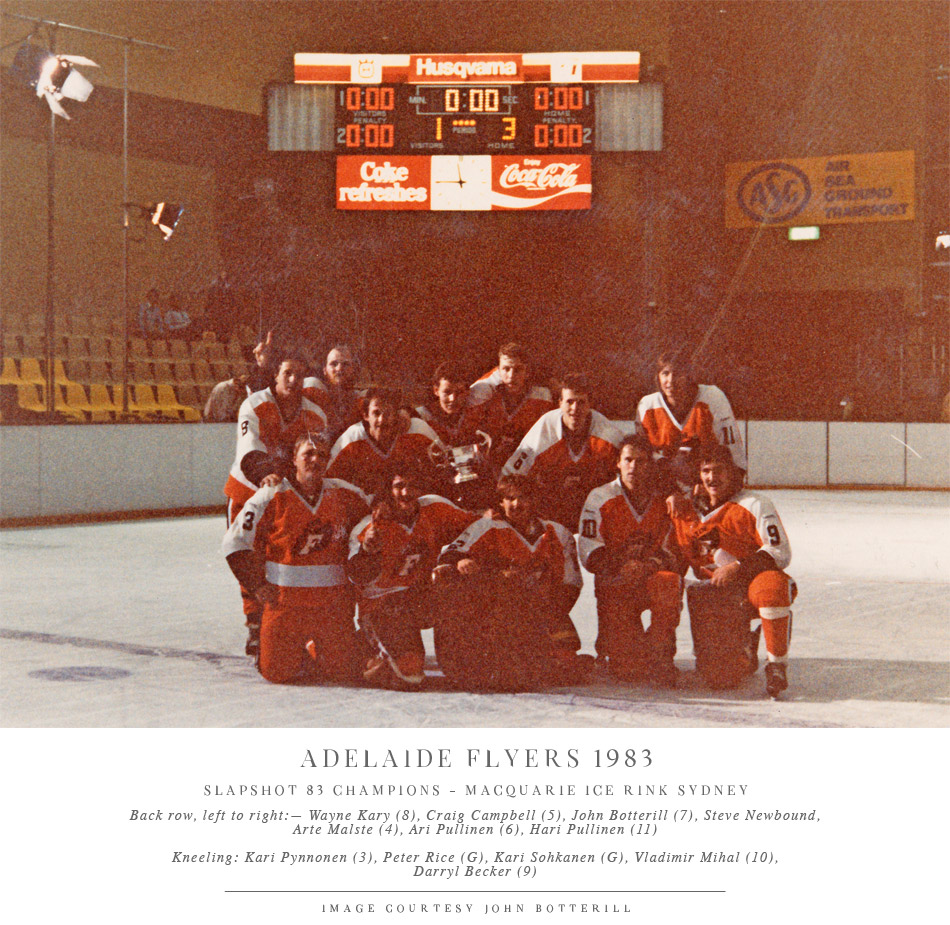

All three signed-up with the Falcons in the local South Australian league coached by thirty year-old Rusty Smith. In 1981, at the age of twenty-four, he lined up with Art Lyon and John Thomas Brown to form one of the deadliest combinations in the NIHL. The Flyers finished on top in the second NIHL season after winning the wooden spoon in the inaugural year.

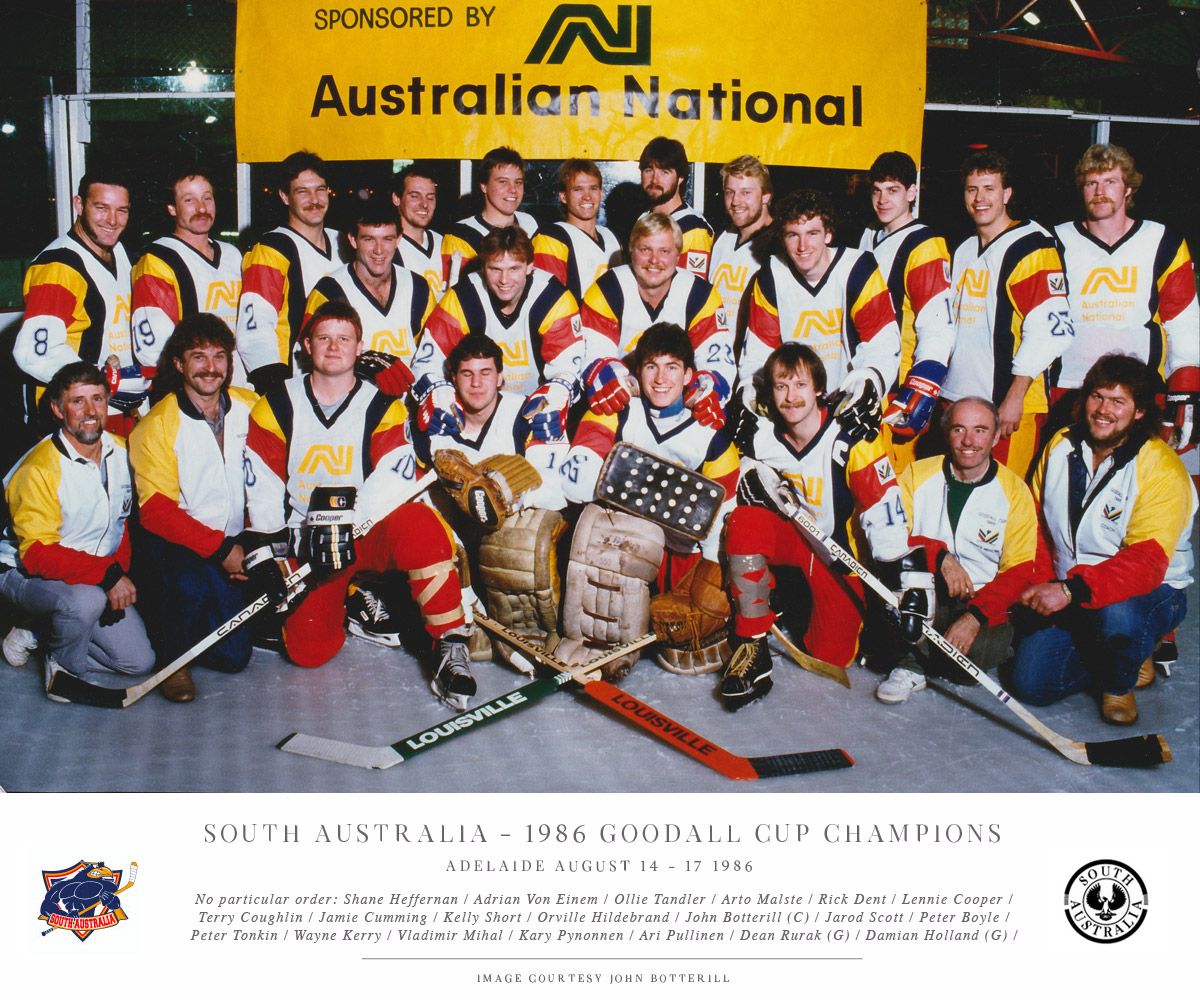

He played with the Falcons for over twenty years until about 2005 and was made Lifetime Member in December, 2002. He was Most Valuable Player in the South Australia A‐Grade in 1987 and captained the South Australian team in the Goodall Cup from 1986 to 1990. He played in the National Senior Team in the inaugural D-Pool in Perth in 1987, finishing with 15 goals 23 assists from 6 games — a scoring average of 6.33 points per game. It placed him in the top-4 players of the tournament and Australia won gold, the nation's first international hockey medal. He also played with the National Senior Team in the Bi‐Centennial Tournament hosted in Canberra in 1988.

Botterill belonged to an era of Canadian expats who played the physical brand of their community game. Violence had been a part of their hockey since at least the 1900s and the organisers of Australia's game had imported it as far back as the 1930s. It has lessened now, supposedly outlawed by IIHF rules, but it was the reason the national association here had shut-down those enterprising eighties leagues, stocked chock-a-block full of overseas players.

Counted among his playing career highlights are those first years with the Adelaide Flyers and winning his state's first National Championship as Captain in 1986, then again in 1987 and '91. Representing Australia and winning gold in 1987 in Perth also factor. As does winning the local A-Grade Championship in 1989 as player-coach of the Falcons after a ten-year premiership drought, and becoming tournament MVP and Division 1 Champions of the Oldtimers league with the Vintage Reds in the first two Adelaide Olympias. Botterill also played several other sports, mostly soccer and soft-ball, and he was a South Australian state champion for several years in the 1980s.

* * * *

Back in 1980, standing on the little patch of land in the Adelaide Hills along Belair Road about fifteen minutes from the city, was like standing on top of the world, watching the sun sink into the ocean, the lights flare up like candles in the dark, the lovers arrive, the thinnest, palest rays of moonlight parting their faces. It was like that, Windy Point. All the necessary special effects for a kiss, a great kiss that sent hearts thumping somewhere below, put all the world at your feet, raised you to a higher state of consciousness, like a lover.

Somewhere there in Adelaide John Botterill met and married Alison who, like him, has now been a coach for over thirty years. Except Alison coaches ice skating. Their son, Trevor, has played ice hockey for local and state teams. Daughter Taylor is a competitive dancer who also plays ice hockey for the the Adelaide Adrenaline of the national women's league, and the former Adelaide Assassins. Coaching the National Women's Team was a career highlight for Botterill, so too was his consultant role with the 2015 squad which included Taylor. The pair were Australia's first father-daughter representatives. Yet, Botterill's coaching career stretches back a lot farther, back to around the time he first clambered out of the Barossa Valley vineyards in search of another hockey adventure.

From 1982 to 1988, he was junior development officer of South Australian ice hockey and state coach at both junior and senior level from 1981 to about 2005. In 1983, he won the Slapshot 83 series with the Payneham Flyers and an Outstanding Performance Award from Sport Australia for 1983 Team of the Year, having been pipped at the post by the racing yacht, Australia II. In 1984, the national association brought out Canadian coach, Clare Drake, to help out at a number of development camps in Sydney, Canberra and Melbourne.

Drake had been head coach of the University of Alberta hockey team in Edmonton for 24 years when he helped Botterill coach the under-18 and under-20 Worlds teams Australia sent to Japan and Italy in March and April 1984. Botterill co‐coached the National Youth Team (U18) for the first four campaigns between 1984 and 1987, winning bronze in 1986 and 1987; and he was Head Coach of the National Junior Team (U21) from 1996 through to gaining re-entry to the World Juniors in Mexico in 2000.

The winless Juniors had taken a long break in 1987. "We thought rather than just jump into the junior world championships, we'd bring these kids to Canada and basically do a three-week tour through good hockey country", said Botterill in 1997. "The objective was to come to British Columbia and really have these kids practice, eat, sleep and live ice hockey". He purposively chose midget-aged skaters with an eye to the future, then in 2000 coached them to their first win against Iceland, 8–4. No more dropouts. Australian Juniors have been competing ever since.

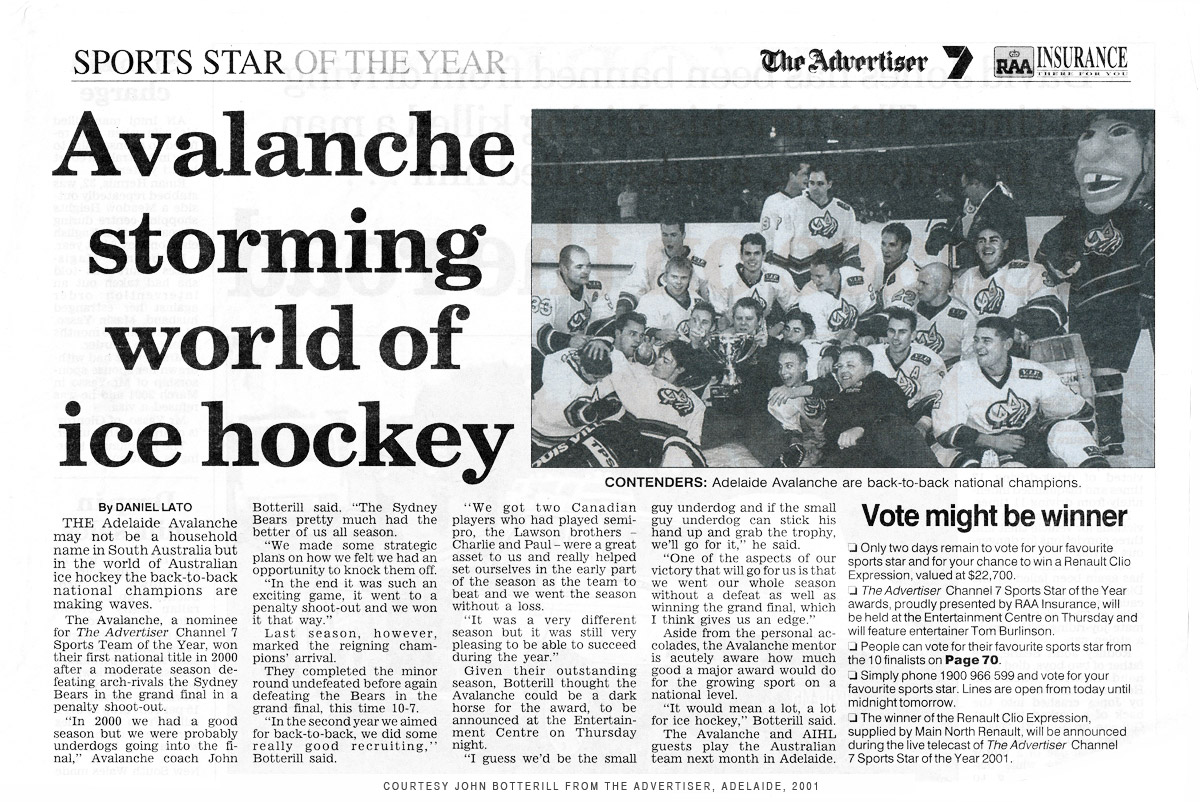

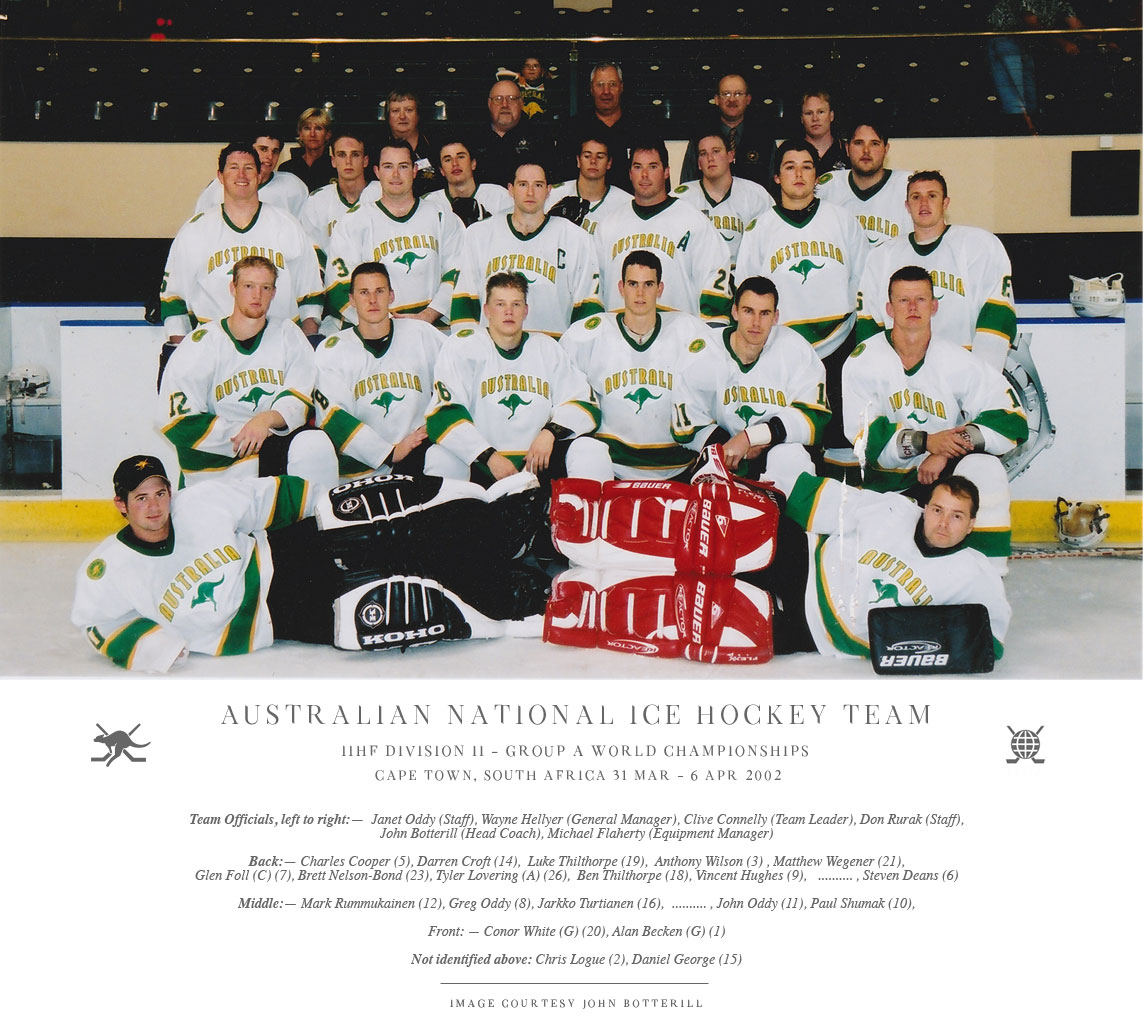

Those years with the Youth and Junior squads are among his coaching career highlights and to cap them off he was appointed Assistant Coach of the National Senior Team in 1996, then Head Coach in 2001. Between 1999 and 2007, he was Head Coach of the Adelaide Avalanche, winning the first two AIHL championships, then Adelaide Adrenaline in the 2008 and 2009 seasons, winning another AIHL championship, the centenary Goodall Cup at home in 2009, and IHA Coach of the Year.

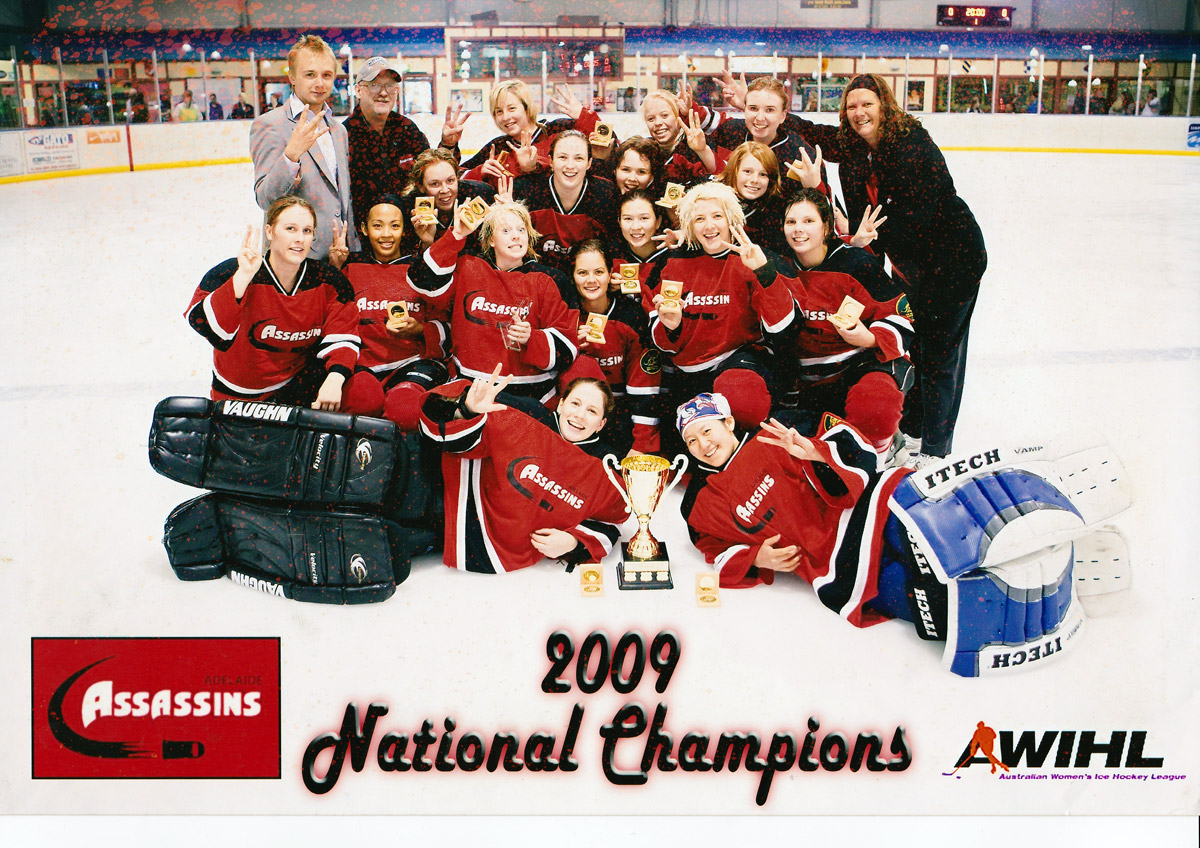

Between 2008 and 2012-13 he was Head Coach of the Adelaide Assassins and the Adelaide Adrenaline women's team, winning three AWIHL championships. In 2015, he was again Assistant Coach and Head Coach of the Adelaide Adrenaline women; Assistant Coach of the 2014 and 2015 National Women's Teams; and a coaching consultant with the 2016 Australian National Women's Team. But you will be disappointed if you think Botterill refueled from all this in the cosy carpeted confines of a corporate office far from ice.

He has been both staff member and manager of The IceArena Adelaide from 1981 until 2002, then its general manager between 2005 and 2012, working with and supporting local, state and national ice hockey and ice sports programs. In 2005, he was a co‐organiser and founding coach of the Ice Factor Program, the only High School ice hockey program in Australia, another highlight in what has now become quite a list. He is very proud of that and its Certificate of Achievement from the South Australian Ice Sports Federation presented by the Governor of South Australia. He was a product of the 1980s, arriving at the very same time that programs were introduced to provide pathways for all participants. Back then, the association even worked closely with the Australian Institute of Sport.

Spanning over thirty years, the career of Coach Botts is the longest in the sport here, and perhaps not yet over. It is one of the most accomplished and certainly the most diverse, producing at the elite level three AIHL championships over a decade, three AWIHL championships over seven years, thirteen internationals with youth, junior, senior men and women. "It has been such a privilege to coach so many local, state and national teams," he says matter-of-fact, "and to assist so many male and female players go on to compete and enjoy ice hockey at so many levels, both in Australia and overseas!" Words like that can leave you feeling a little blasé, but when they are said with such practicality, the unblemished facts devoid of calculation, you cannot help but wonder what is really going on. What drives that passion?

His brother Cal, a PhD and professor at the University of Winnipeg, is a recipient of the Sport Manitoba Award of Excellence. He has helped some of Canada's top athletes reach personal bests and co-authored a book called Perspective: the key to life. Cal devoted his own life to the study of the performance of elite athletes, especially hockey, so there is no escaping the question of what John Botterill thinks about Australia's variable performance on the world stage. He will almost certainly tell you Australia's international ice hockey results reflect the limitations of a minor sport, always fighting for support and exposure, always short of finance and reliant on volunteer contributions and sponsorship. Yet, you ask anyway.

"There are challenges and hurdles that will continue to be critical in our striving to improve our world ranking that I have experienced from my early days in the 1980s to current times," he says. "The availability and standard of ice sport facilities is a major factor in the numbers of persons and players that have the opportunity to experience and take up ice sports". Quick to add there are now some new facilities and others on the horizon which should greatly assist, he also points to the limited funding of most small sports. "Most local and state teams are self-funded by players, a few with sponsorship assistance". It's pay to play and the sport here is also reliant on the contributions of many administrative and coaching personnel who are volunteers, as far as he is aware — from our local competitions in each state, to our national program and national association.

Botterill had to fund himself to coach in his first two years with the National Youth Team in 1984 and '85. These days, he says, coaches and managers are assisted at state and international level, but just as the best players are not always available because they simply cannot afford the costs year after year, so too do coaches face cost and time pressures in supporting and developing players and programs. Financial stress can lead players and coaches to give their education or employment higher priority than their availability to play for their state or country.

"I have such admiration for all these players, past and present," he says, "who make many sacrifices to play this great game with so much passion and commitment!" And perhaps this is also not surprising coming from a man who traveled to the other side of the globe to play and teach it, a man who made his home there, far from the madding crowd of his sport's centres of excellence, a man who took whole teams back there on study tours.

Over there, his nephew Jason Botterill, Cal's son, is the only Canadian to ever win a Gold Medal in three straight World Junior Hockey Championships. Jason helped lead the Wolverines to an NCAA national championship in 1996; won the 2001 Calder Cup in the AHL with the Saint John Flames; and played in 481 professional games, including 88 in the National Hockey League with the Dallas Stars, Atlanta Thrashers, Calgary Flames, and Buffalo Sabres. More recently, he twice won Stanley Cup rings as an administrator with the Pittsburgh Penguins.

His niece Jennifer Botterill, Cal's daughter, was National Champion with Harvard University and two time Patty Kazmier winner, the best women's college player in the USA. She still holds the NCAA records for "most consecutive games with a point" and for "most points in a hockey career". She was a member of the Canadian Women's Hockey Team from 1997 to 2011 and she has competed in four Olympic Games. Jennifer is a three time Olympic Gold Medalist (2002, 2006, 2010); an Olympic silver medalist (1998); and a five time World Champion, twice named most valuable player. An Athlete Ambassador with the International Olympic Committee and the International Ice Hockey Federation, she has gratefully and quite publicly acknowledged the support of the Canadian Athletes Now Fund, even on YouTube video.

His own daughter Taylor started ice skating at sixteen months — no choice with a father hockey coach and a mother skating coach! She started playing at about sixteen years, but due to years of following her parents about, her skating skills enabled her to pick-up quickly and make the State Team. Selected to represent Australia at the age of twenty-three, she raised over $2,000 on GoFundMe to help her get to Jaca in Spain for the 2015 Division 2 Women's Worlds. None of the six or seven hundred athletes supported by the Australian Institute of Sport's Direct Athlete Support program are ice hockey players.

To keep that in perspective, even Australian athletes heading to the 2016 Olympics in Rio had turned to the crowd-funding site GoFundMe to achieve their Olympic dreams. But Australian ice hockey does not even qualify as an Olympic sport today, and nor will it without funding. This next generation of the family, including Jason and Jennifer, are heavily involved with coaching or promoting ice hockey just like their fathers and uncles. It seems it's in their blood.

"Ice hockey [in Australia] has now become so much more available thru Fox Sports and the internet", says John Botterill, "and this along with the development of the AIHL and AWIHL will assist the general awareness of the game". And then the penny drops. Cal would say his brother has "perspective" — he is grateful, he has poise, he can see the big picture, he can focus, he can relate, he has natural energy and he has character. He is able to live his life in a "want to" versus "have to" way, and optimize his health, happiness and performance. He is up at Windy Point. Mickey Sutherland said the same thing in a different way back in 1981. "Botterill just "keeps on truckin'," he wrote. "He just motivates himself to perform at the best of his ability in whatever he does. He is about as good an exponent of this philosophy you could find anywhere".

"Our challenge", John continues, "is to keep moving forward and take advantage of this [increasing awareness] to get more players and personnel involved in the sport. As well, if we can get to the point of making it more affordable for our players and coaches to be able to commit the time and energy to create stronger programs to develop elite players, it will help us climb the world rankings". There is little doubt things get easier once a sport achieves critical mass. It becomes self-sustaining and creates further growth. It generates more revenue for reinvestment back into players and coaches. Will that help Australia's world ranking? Yes, of course. It is a factor.

When it comes to elite performance, perspective can make a difference. So said Cal to the 2005 annual convention and general meeting of Skate Canada. Those who have it are usually humble and love what they are doing. For them life is much more "privilege" than "responsibility". Great players and coaches are not looking for the easy road. They do not want lowered expectations; they want more and greater challenges. Retired Australian defenseman, Jarrod Scott, who was coached by John Botterill from a young age, says his former coach will do anything to get the most out of his charges.

"Players will respond," Scott explains, "because John is a person you just don't want to let down. He is, in the true sense of the saying, 'a player's coach'. I have played with him and for him, and every time was a privilege. He is more than just a great coach, he is a great friend. Australian hockey is in a better place because of his knowledge and love of the game. He didn't just coach hockey players, he gelled teams together and taught life lessons".

In December 2021, a Jury awarded John Botterill Honoured Membership of the Hockey Hall of Fame Australia for his outstanding and inspirational contribution to the game.

Fifty images from John's hockey career are divided between the three galleries beneath the three large photos on the page. Use the arrows to scroll the thumbnails.

NOTES AND CITATIONS

1. Australia's National Youth Team had a big improvement from 1984 to 1985, but did not win a game in South Korea. The Bronze medal attributed in some sources to Australia's National Youth Team in 1985 is incorrect. They won Bronze in 1986 in Adelaide (Coach Botterill).

2. In 1986, Simon Allatson, National Ice Sports executive director, said "a number of Eastern bloc and Asian countries had utilised full-time sportsmen who ostensibly play for a living." (Canberra Times, 2 Mar 1986:4) In 1987, North Korea were awarded the Bronze Medal at the IIHF Asian Oceanic U18 Championships, but were ultimately disqualified for a breach of competition rules. Team Manager, Sandi Logan, pursued the matter and a few years later it was proved at a Senior World Championship that most of the players had been well over the age limit for the 1987 Under-18 tournament. The Coach and players of the 1987 Australian National Youth Team received their Bronze medals in the mail.

3.The Daily News, Canada, 1997, "Aussies on ice hoping to join world powers".

4. South Australian Allsports News, 1981, Mickey Sutherland, Flyers "Take Off" with Botterill.

5. Skate Canada, June 9 - 11, 2005, Cal Botterill and Tom Patrick, "'Perspective' can make a difference", paper presented to the annual convention and general meeting.

6. Biographical notes from John Botterill, August 2016

7. Edmonton Journal, Canada, July 29 2000, Lynn Lau, "Enjoying snow and ice in Australia, Canadian Prairie boy finds a new career, bringing our climate to people Down Under".

8. The Canberra Times, Australian Capital Territory, 13 Jan 1984, Canadian Coach Impressed.

9. Botterill was made a Life Member of the national ice hockey association in Australia after writing (November 2016).