BUD MCEACHERN WITH THE MONARCHS ICE HOCKEY CLUB, VAIHA PREMIERS, 1959 (STANDING SEVENTH FROM LEFT)

Front row, from left: P Parrott, M Hannah, I Vesely, R Dunn, B Hansen (C), D Siemens, B Acton (VC), A Deane

Standing: B Henderson (Treasurer), R Leonard (Referee), M Dyer (Committee), R O'Bryan (Trainer), R Carson (Coach), J Mitchell,

W McEachern (Committee), J Nicholas, A Munsie, K Pawsey, E Mustar, F Gladwell, W Yano, F Cobbin, A Reid, S Meredith (Vice Pres),

Harold E Barry (Pres and Mgr) R Bungey (Vice Pres) [17]

Insets from left: J McCrae-Williamson (Sec), H H Kleiner Trophy, W Walton (Asst Sec)

Outside In

Bud McEachern and the Olympic outsiders

![]() "The stick went through his throat. It was a very intentional type of injury and three of the others were injured, so the boys really were slaughtered for that reason. And, of course, the rules, while they're the same, the interpretations were different, so that international experience they lacked. That was the only team they sent... that taught me a lot.""

— Geoff Henke, former Australian ice hockey player and Australian Olympic Committee official, speaking about the first Australian Olympic ice hockey team at the 1960 Winter Games, Sydney, 2008. [2]

"The stick went through his throat. It was a very intentional type of injury and three of the others were injured, so the boys really were slaughtered for that reason. And, of course, the rules, while they're the same, the interpretations were different, so that international experience they lacked. That was the only team they sent... that taught me a lot.""

— Geoff Henke, former Australian ice hockey player and Australian Olympic Committee official, speaking about the first Australian Olympic ice hockey team at the 1960 Winter Games, Sydney, 2008. [2]

Palais des Sports, Paris, 1930s. Host venue of the 1951 IIHF World Championships.

Palais des Sports, Paris, 1930s. Host venue of the 1951 IIHF World Championships.

THE PANORAMIC VIEW OF THE EIFFEL TOWER from the Pont de Bir-Hakeim over the Seine is especially breathtaking between Passy and Bir-Hakeim. The clatter from Formigé’s steel viaduct changes abruptly as the train passes over the masonry arch, then resumes. Nothing disturbs the lovers seated opposite, her thoughts still lie kitten-curled in his when the clickety-clack of steel on steel grinds to an end. C'est cela l'amour.

I rise at the Bir-Hakeim stop on the left bank, the station closest to the Eiffel Tower, but not for Gustave’s global icon, nor the replica Statue of Liberty just visible at the western tip of the Isle of Swans, a gift to The City of Light from French expatriates in North America.

Out on the Boulevard de Grenelle, near the station exit, I stop to read the plaque acknowledging the 13,152 Jews arrested and held here under inhumane conditions by the Vichy government. My French is ordinary, but I do know these words. I wrench my eyes away, suppressing a feeling of foreboding, and fix them on the corner of the rue Nélaton where once stood the former Vélodrome d'hiver, the Winter Velodrome. The Vel' d'Hiv.

The block of flats and the government building show no signs of their predecessor, but with eyes closed I recall the glass-roofed stadium once frequented by Hemingway, "... the smoky light of the afternoon and the high-banked wooden track and the whirring sound the tyres made on the wood as the riders passed." With the sheet of ice in the middle and the crack of vulcanised rubber pucks and the hissing sound the blades made on the ice as the skaters glided by.

Rechristened the Palais des Sports in the Thirties, its former name remained in use. The Français Volants ice hockey team set up here soon after Jeff Dickson replaced the roller skating rink located inside the track with a 60 x 30m ice sheet. It was here in 1936, on this now infamous corner, that Australia’s professional skating pair, Albert Enders and Sadie Cambridge, performed for Paris one last time and played ice hockey before 15,000 cheering fans.

Here too, fifteen years later, the coach of Norway’s ice hockey team produced the nation’s all-time best IIHF tournament result. Fourth in the 1951 World Championships, Bronze in the European Championships, results of little importance to Australian ice hockey you might say. But really they were, in an unexpected way.

On the evening of March 9th, the goaltenders from thirteen countries led their team’s procession to the line-up carrying their national flags, and stood in silence for the welcome from IIHF president Fritz Kraatz and La Marseillaise. The incredibly steep, double-tier stands were all but empty, the fans arriving around 9 pm for the start of the first game advertised later than scheduled. The French-sounding surnames of the Americans intrigued everyone. The Bates Hockey Club of Lewiston were mostly workers from Maine's largest employer, many from across the border in Quebec.

Within two minutes of the first face-off, an American player dropped Norway's Bjorn Gulbrandsen neck first to the ice. Doctors at a nearby hospital gave him a 6-month holiday. Body checking was legal, but not often used by Europeans. Neither the European players or spectators liked it, and teams from North America were commonly criticized for rough play. The Norwegians were used to a less physical outdoor game, but compensated with better skating and team play.

With the fans behind them, not the French-speaking Americans, Team Norway dominated a scoreless first period, scored at the start of the second, and added two more in the third. A shutout USA, but losses followed to Switzerland 8-1, Canada 8-0 and Sweden 5-2. Then on March 15th, down 2-1 in the second against Great Britain, the Norwegians produced 3 goals to 1 to steal a second victory. [6] Meanwhile, a collection of recreational players went from Cinderella team to national treasure in the wave of a wand. The Lethbridge Maple Leafs won the championship representing Canada.

The coach who led the players in the white uniform with red stars to their best finish, fourth in the World, was not Johan Narvestad who led Norway's 1950 campaign in London, nor Trygve Holter who led them for most of their existence. It was a 30 year-old Canadian-born rookie named Bud McEachern. The association considered his physical style well-suited to the players of that generation, so he replaced Narvestad.

The next year, McEachern coached Norway's first Olympic ice hockey team at home in Jordal Amfi, Oslo. Assisted by Carsten Christensen, one of the nation's hockey pioneers, they were competitive in the top-level against Poland 3-4, the USA 2-3, and even the Swedes 2-4. But they were soundly beaten by Canada 0-8, the Czechs 0-6, the Swiss 2-7, the Finns 2-5 and the Germans 2-6. Norway finished last in their first ice hockey Olympics and missed the next Worlds, but returned in 1954 with Christensen as coach.

Canada's last Olympic gold in men's ice hockey for fifty years signalled a slow drift toward the European-style game, but none of McEachern's successors were able to repeat his results. Norway did continue to challenge the strongest hockey nations over the next ten years, but ice hockey there slipped into decline from the 1960s. [399]

Years earlier in May 1941, McEachern's fan reception was a little different. An estimated 7,000 people jammed into Queen City Gardens to watch the Regina Rangers, Canada's Western Champions, cap their season by clinching the Allan Cup. [4] Considered second in prestige only to the Stanley Cup, this trophy is Canada's top senior amateur hockey prize.

The Eastern Champions, Nova Scotia's Sydney Millionaires, arrived in Regina as favourites with Bud McEachern onboard and coach Bill Gill who had won two Allan Cups with the Moncton Hawks. [5] Along the way, the Millionaires defeated Hull Volants in three straight games to advance to the Eastern final against the Montreal Royals. The Royals, with future NHLer Bill Durnan in goal, tied Sydney 3–3 and won the second game 3-1, before dropping the next three.

One of the strongest teams to ever come out of Cape Breton, the Millionaires with McEachern on the wing were Maritime Champions in 1940. On the road to the 1941 Allan Cup final, they won the first two games against the Rangers, 8-6 in Calgary and 8-3 at Regina. When the third tied at 1–1, the organisers adjusted the point system so that the first team to 6 points would win the Cup.

The Millionaires, on 2 points for each win and 1 for the tie, only needed a tie to win. But the Rangers did not give it up so easily. They battled back in the fourth and fifth games at the Gardens, defeating Sydney 5-4 and 6-5 respectively to force the decider.

The springtime conditions and the Grand Final crowd conspired to tax the Gardens' ice plant. A thick fog rose on the ice surface, whiting-out players and puck. Determined to win in front of a large home crowd that was heard but not seen, the underdogs blanked the Millionaires in a 3-0 victory, "Sugar" Jim Henry registering the shutout.

Regina were the farm team to the New York Rangers, so many players went on to the NHL including Henry, Garth Boesch, Grant Warwick, Gord Davidson, Scott Cameron and Frank Mario. Among the Millionaires, Dickie played a game with the Chicago Blackhawks, Walton played four with the Montreal Canadiens, and McCreedy won two Stanley Cups with the Toronto Maple Leafs. After the war, McEachern played a season for the Truro Bearcats in the MSHL, then moved to England in 1947.

At that time, the English National League was the biggest amateur league in the world, attracting some of Australia's top skaters. Melbourne professional skater Albert Enders had made London his base twenty years earlier. Sydney's Jimmy Brown played with the Grosvenor House Canadians in London and represented Britain both there and overseas. Ken Kennedy had just moved there from Australia to further his skating and hockey career with help from Enders. Britain won World Championship medals in those years, but the bronze won at the 1924 Games and the remarkable gold in 1936 were distant memories. The national team was struggling.

Many English clubs recruited their players direct from North America with newspaper advertisements. McEachern was 26 when he arrived, born William Oliver on February 19th 1921 at Charlottetown on Prince Edward Island. [14] He grew up playing Right Wing in Nova Scotia's Maritime Senior Hockey League before moving to Cape Breton [19] and then England in his prime. He played three seasons for London's Streatham in the English National League between 1947 and '49, and against his native Canada on 20th March, 1948. The RCAF Flyers represented Canada, the nation's 1948 Olympic Gold Medal team. [13]

McEachern scored 56 goals in the 1947–8 ENL season, the 4th-ranked league goal-scorer and 10th overall on 80 points. Next season, Streatham were runners-up to Harringay Greyhounds. In the Autumn Cup that year, he scored six hat tricks, but that was four fewer than Winnipeg-born 'Chick' Zamick (1926–2007) of Nottingham Panthers who top scored with 40 points, and 41 in the International Tournament.

Chick was later inducted into both the British and Manitoba Hockey Halls of Fame. McEachern was his closest rival in the late-1940s. Art Hodgins also played with McEachern at Streatham, arguably the best defenceman to play in post-war Britain. Another Hall-of-Famer who many believe could have made the NHL.

Years later when Streatham hockey historian, Allan Palmer, assembled his Streatham Dream Team, he chose McEachern on the right wing to partner centre, Gordie Knutson. "Bud was a burly fellow," he wrote, "who could face the toughest defenders and still thrive. He was quick for a big man and...this is the point, he was absolute poison round the net. Phil Drackett once observed that Zamick was a 'snapper-up of ill-considered trifles' and so he was, but Bud McEachern was not that far behind..."

McEachern left Streatham for the Earls Court Rangers early in the 1949-50 season, arriving with British Hall-of-Famer, Les Anning, who was voted to the All-star team twice in his three seasons at the club. Coach "Duke" Campbell, the first inductee to the British Ice Hockey Hall of Fame, had a record at the time of 359 consecutive league and cup appearances in the ENL. Next season, McEachern played for the Harringray Racers, then returned to the Rangers in 1951–2, the year he turned 30. It was his last season in the ENL. He had taken the top job with Norway's national ice hockey team.

OLYMPIC FEVER ENVELOPED AUSTRALIA when Melbourne was selected by a one-vote margin over Buenos Aires to host the 1956 Summer Olympics. "Melbourne Gets the Games" headlined the Victorian press at the end of April 1949. Front page news. Curiously, the year before, The Age newspaper suggested "the Olympic winter sports, which are always held independently of the main Games, could be conducted at Mt Buffalo, Hotham or Koscuisko (sic)."

Indeed, the Victorian ice hockey association gained admittance to the Australian Olympic Federation in 1950, and re-established an Olympic Fund in 1954. But, in reality, winter sports were far from the minds of members of the Victorian Olympic Committee, especially its secretary-treasurer, Edgar Tanner. Although ice hockey was close to the hearts of Canadian expat Russ Carson and his small group of devotees, only one ice hockey player came close to the 1956 Games, and that was to carry the Summer Olympic torch.

The Monarchs ice hockey club in Melbourne had grown from strength to strength in the Forties under Carson's coaching and administration. By the Fifties, the club boasted top homegrown players such as Benny Acton who represented Australia in Olympic field hockey, Bas Hansen, Johnny Nicholas and Ed Mustar, plus a few of the more promising New Australians, including Peter Parrott and Ivo Vesely. Carson was also vice-president of both the Victorian Amateur Water Polo Association and the Melbourne Collegians Water Polo Club in which Parrott and Nicholas competed.

Immediately after the 1952 Olympics with Norway, McEachern moved to Melbourne, joined the Monarchs in his early thirties, and won the 1952 and 1954 Goodall Cups representing Victoria. His interstate début at St Moritz in 1952 produced a 12-2 winning margin, the biggest since Victoria shut out New South Wales 12-0 in the second match of the second Goodall Cup forty-two years earlier in 1910.

"Victoria's huge tally was mostly due to the powerful work of English National League star, Bud McEachern," observed the local press. [3] Paired in defense with Hungarian-born Tommy Endrei, he was "impassable and almost continuously turned defense into attack by 'setting up' his forwards with perfect passing and position[ed] play". [3] A powerful, opportunistic quarterback of two forward lines — Derrick-Kurzweil-Henke and Jones-Sengotta-Cunningham — he won Best Player over Endrei, his brilliant D-partner.

The die cast, Goodall Cups rolled off the line, '52, '53, '54, '55, until Sydney Glaciarium closed, creating a hiatus of five seasons between 1956 and '61. McEachern's presence in local hockey was wood on the fire of Victoria's all-time boom years. Carson and he converted the broken stranglehold of their rival's pre-war dominance into a state dynasty, inflicting a retributive dominance of the coveted trophy for 35 years.

McEachern was also a cool head in a rapidly changing and often overheated local league which the Raiders, half composed of New Australians, had come to dominate with speed and skill. His Monarchs were the 1952 runners-up to the Raiders. When he turned 33 in 1954, there was talk about retiring from playing, but that was still years away. At 36 he won the 1957 Spot Lloyd Trophy for Most Points in the Victorian League.

When he had an off night, so too did his Club, but they battled on for seven seasons against the domineering Raiders and then the Blackhawks. Sometimes undefeated in the regular seasons, they finished in second place three years running, until at last they won the 1959 Kleiner Cup. The Club's B-grade also won the Premiership.

Unavailable from early in the season, McEachern only played three games, but finished fifth in the count for the President's Medal, the state's Best and Fairest, won by teammate, Ivo Vesely. McEachern was still best on the ice at 38 in each of the three games he played, with the maximum three Medal votes from each encounter.[15]

Appointed coach of the first Team Australia, Bud McEachern set about the task of shaping an Olympic ice hockey team for the 1956 Games in Cortina with Carson as manager. When all was in readiness, the association lodged a request with the AOF seeking permission to compete and pay their own way, but they did not receive a reply.

Unable to attend, they criticised the AOF for their disinterest. Good players were lost from the Olympic squad, including future trucking magnate, Lindsay Fox, and future Winter Olympic sports administrator, Geoff Henke, who represented Victoria nine times over thirteen years, including the state captaincy in 1959.

Redoubling the Olympic effort, McEachern asked Henke to return to the squad for the 1960 Winter Olympics in Squaw Valley USA, but he had taken over his father-in-law's business, Molony's Boot Shop in King Street. "What if I join the squad and train hard, it would be to the detriment of my business or the business I'm trying to develop further, Molony's ... established since 1854 — I have ideas for that business — and I don't make the team? I've wasted a year".

McEachern returned a month later with a different offer. "Look, the squad's just starting now, I've solved your problem, you're the Assistant Coach of the Olympic Team to me, so you're picked, you're the first to be selected." Henke thought about it, weighed it up, but in the end went back to developing the boot business into Molony's Ski Hire and related enterprises.

"The team went to Squaw Valley," Henke recounted, "and they were slaughtered. Not because of their own fault, just the lack of training, the financial backing they did not receive, and things like that. The players...most of them had never skated on outdoor rinks...the Olympic competition was outdoors... which wouldn't happen these days of course, there's no outdoor rinks. They had no international training or competition against other teams. Some of the fellows that I played with had come from Czechoslovakia, etc and were naturalized...

"...they went out to their first game and because they defected from Czechoslovakia, still a communist country, the Czechs went for them and my centre man, Ivo Vesely, finished up in hospital after the first game. The stick went through his throat. It was a very intentional type of injury and three of the others were injured, so the boys really were slaughtered for that reason. And, of course, the rules, while they're the same, the interpretations were different, so that international experience they lacked. That was the only team they sent... that taught me a lot." [2]

Australia relied on McEachern's coaching experience and the off-ice expertise of English promoter, Bunny Ahearne. Carson regularly sought the advice and financial assistance of Ahearne, secretary of the British Ice Hockey Association and IIHF president during the preparatory years of the Australian Olympic campaign, 1957 to '60. Experience with Britain's world-class Olympic and European ice hockey teams of the 1930s was invaluable, and Ahearne's influence in the IIHF helped build confidence. Over-relied on, it led to setbacks.

Committee-man of the Monarchs when Carson was Coach, the Victorian ice hockey association appointed McEachern junior vice-president in 1959. From 1960 until '69, Carson held sway over the national ice hockey association as secretary and treasurer, delegate to the State Olympic Council, and Victorian delegate through his water polo club to the Australian Olympic Federation.

McEachern succeeded George Hewitt as Victorian association president for two terms from 1960, the Olympic year, after which Kurt Defris took over. During his administrative years he worked with three association Executive Committees, composed variously of Defris, Stan Gray, Rus Jones, Clarrie King, John McCrae-Williamson, Doug Munro and Rex Bodin.

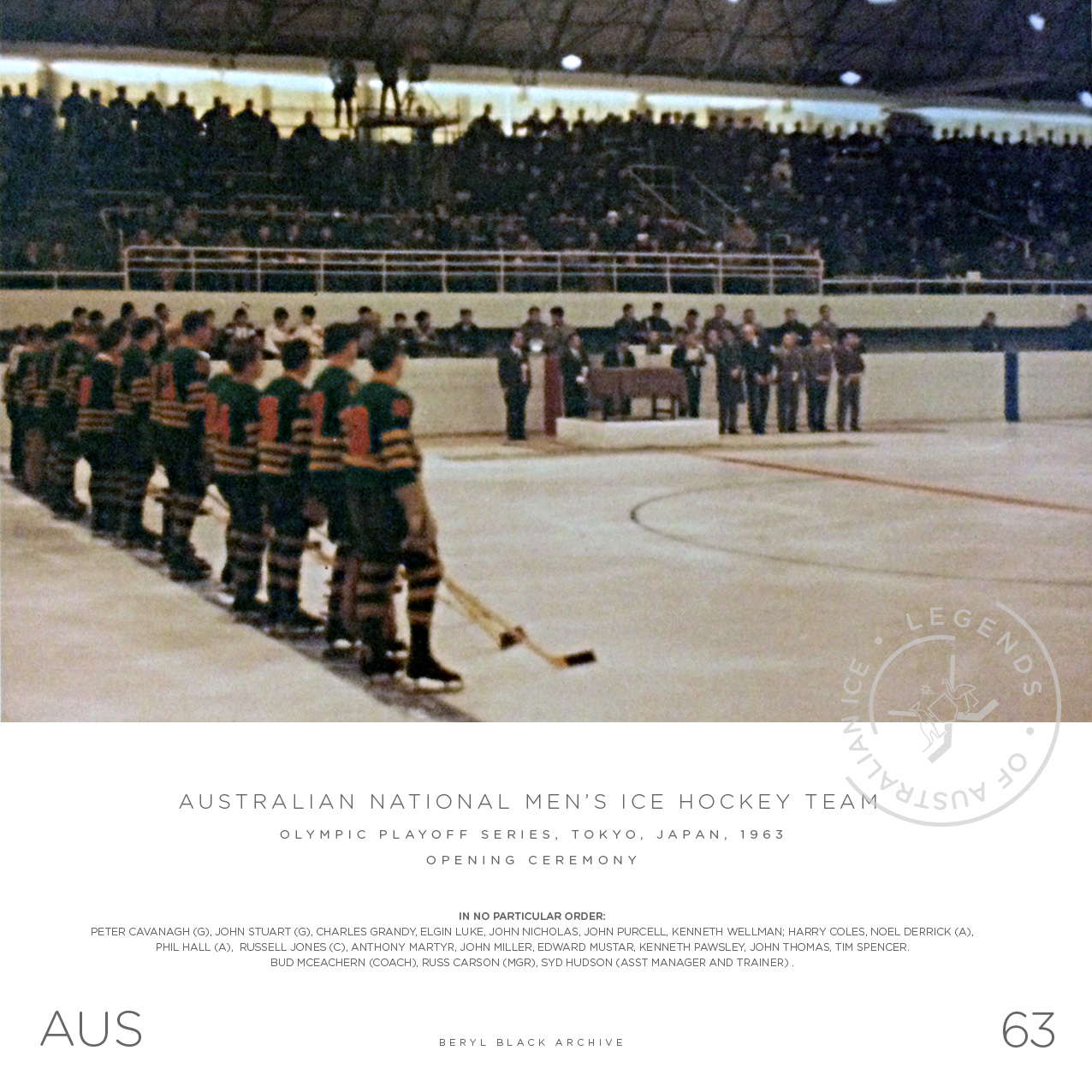

Ken Kennedy's appointment as coach of the 1962 Worlds team quickly soured when he withdrew less than a fortnight before departure, leaving Carson to take away a coach-less squad. McEachern returned to guide the unsuccessful 1964 Olympic Qualification team, the only coach of Australia's Olympic ice hockey campaigns up until the present time. The Victorians shouldered the debt and disappointment with a little help from their friends.

Straddled between their hockey backwater and their Olympic dream, the sport's organisers in Victoria took elimination from the 1964 Games like the bitter pill it was. "Have a good look at yourselves" they were told by the more pompous among the Olympic bureaucrats. Instead they plotted a triumphant return at the 1967 Worlds, then the 1968 Games in Grenoble, while the debate they triggered raged on over Olympic selection standards versus participation.

A whole decade went by before Australia returned to the ice hockey world championships at Grenoble in 1974, and no ice hockey player has carried the torch since Rus Jones at the Summer Games all those years ago and Noel Derrick when the Summer games returned in 2000.

McEachern lived on in Melbourne for more than half his life, a retail sales manager at Southern Motors at the top end of Elizabeth Street in the City. [16] Like Holden dealer, Bib Stillwell, he continued to win awards, but with one of the oldest names in Australia's motor car trading history. He died at 77 on April 11th 1997. In 2000, he was post-humously elected a Life Member of both his state and national associations, along with all the ice hockey outsiders who descended on Squaw Valley USA forty years earlier.

His was a career spent face-to-face with some of the legendary players and coaches of the time, on both sides of the red circle, on both sides of a traveled world. Long after it was over, Geoff Henke thought of him as "most probably the greatest hockey player [we] ever had in Australia". [2]

BUD McEACHERN & ANDY CLARKE, Victorian Ice Hockey Association, Melbourne, 1957.

Spot Lloyd Trophy winner, Bud McEachern (left), and President's Medallist, Andy Clarke, in action.

Sydney Millionaires

At 20, 1941 Allan Cup Runners-up, Nova Scotia, Canada. Front Row: Ed Tucker (Trainer), Bobby Walton, Jud Snell, Jack Atchison, Remi Van Daele, John McCready, Dick Kowcinak, Art Bennett (Trainer). Back Row: Keith Langille, Ray Powell, Mel Snowden, Bud McEachern, Jack Fritz, Grant Hall, Steve Latoski, Bill Dickie (Goal). Image source: Lloyd McDonald, Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, Canada.

Streatham

At 26, English National League, London, 1947-8. Back row, left to right: Red Stapleford (coach), Norm Gardiner, Gunnar Telkinen, Doug Wilson, Bud McEachern, Paddy Ryan, Chuck Turner (C), Larry McKay, George Baillie, Archie Stinchcombe, Bob Mallard (trainer). Front row: George Drysdale, Dave Miller, Monty Reynolds, Harold Smith, Ross Richardson, Vern Gardiner. Image source: Ice Hockey World Annual.

Streatham

At 28, English National League, London, 1949-50. Standing, left to right: Ken Campbell, Paddy Ryan, George Edwards, Bob 'Doc' Brodrick, Elwood Small, George Baillie, Dave Miller, Art Hodgins, Buddy McEachern (who left for Earls Court early in the season), Red Stapleford (coach). Seated: Mike Yaschuk, Johnny Sergnese, Harold Smith, Keith Woodall, Zip Thompson, Jim Campbell. Image: Streatham Ice Hockey Club. Gunnar Persson, Martin Harris and Kris and Richard Hodgins (son of Art) helped with identification.

[1] The 1941 Millionaires team were Bud McEachern, Keith Langille, Mel Snowden, Ray Powell, Jack Fritz, Grant Hall, Steve Latoski, Jack Atchison, Remi Van Daele, Judd Snell, Bobby Walton, Johnny McCreedy, Dick Kowcinak, Bill Dickie, Art Bennett (Trainer), Bill Gill (Coach), Ed Tucker (Trainer). [19] Gill played for Moncton Hawks in New Brunswick, Canada, including both their Allan Cup wins (1933–4). Kowinak won Allan Cups in 1939 and '40.

[2] Geoffrey Henke interviewed by Bob Stewart for the Sport Oral History Project, sound recording, May 6, 2008, National Archives Australia

[3] Vic Beats NSW at ice hockey, Sporting Globe, 26 Jul 1952.

[4] The Allan Cup was donated in 1908, a year before Australia's Goodall Cup, by Sir H Montagu Allan as a trophy for amateur teams. It replaced the Stanley Cup, which by then had become a professional competition. These three trophies, the Stanley, Allan and Goodall are the oldest National ice hockey prizes still contested in the world.

The Allan trophy was originally presented to the Victoria Hockey Club of Montreal to award to the champion of their league, who could then be challenged by champions of other leagues. The first winners of the Cup were the Ottawa Cliffsides, and the first successful challengers were the Queen’s University club of Kingston, Ontario. In the early years of the Cup, its trustees quickly came to appreciate the difficulties of organizing a national competition in so large a country.

In 1914, at the suggestion of one of the trustees, the Canadian Amateur Hockey Association (CAHA) was formed as a national governing body for the sport. The next year, it replaced the challenge system with a series of national playoffs and turned over responsibility for the Cup to the CAHA in 1928. Allan Cup Champions also represented Canada at the World Championships until 1964.

[5] The 1933 Moncton Hawks played their series at Vancouver and defeated the Saskatoon Quakers 2 games to zero. In 1934, the Moncton Hawks were again Amateur Champions of Canada and Winners of the Allan Cup. This time they faced the Fort William Blues at Maple Leaf Gardens. The Hawks won the series 2 games to 1. Postcards are in the estate of Aubrey Webster who played both years.

[6] European Ice Hockey Championship results since 1910, Tomasz Malolepszy, 2013.

[11] Springvale Botanical Cemetery, William Oliver McEachern

[13] Streatham Programme 1948-49, Saturday 20th March 1948 - Streatham v Canada.

[14] The Internet Hockey Database, hockeyDB.com. Online

[15] Ice Hockey Guide, VIHA, September 14th 1958.

[16] Pointers magazine, General Motors-Holden's Pty Ltd, Vol XXV No 10, Nov 1961.

[17] Harold Barry, president and manager of the Monarchs, was involved with the 1960 Olympic team, but unable to go due to illness. His family has souvenirs and program signed by all players. (Shaun Havoc email, 3 Feb 2018)

[19] Lloyd MacDonald Web site, Sydney, Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia, Canada.

[40] Society for International Hockey Research (SIHR)

[399] Norway men's national ice hockey team, Wikipedia, quoting Langholm, Dag (1984), Norsk ishockey gjennom 50 år. p 97.

Image: The opening ceremony of the 1951 IIHF Ice Hockey World Championship in Paris. Photo Courtesy James Sinclair collection. IIHF.

Image: Spot Lloyd Trophy winner, Bud McEachern, and President's Medallist, Andy Clarke, in action. From the original in Ice Hockey Guide, VIHA, 15 Sep 1957.