GLADIATOR

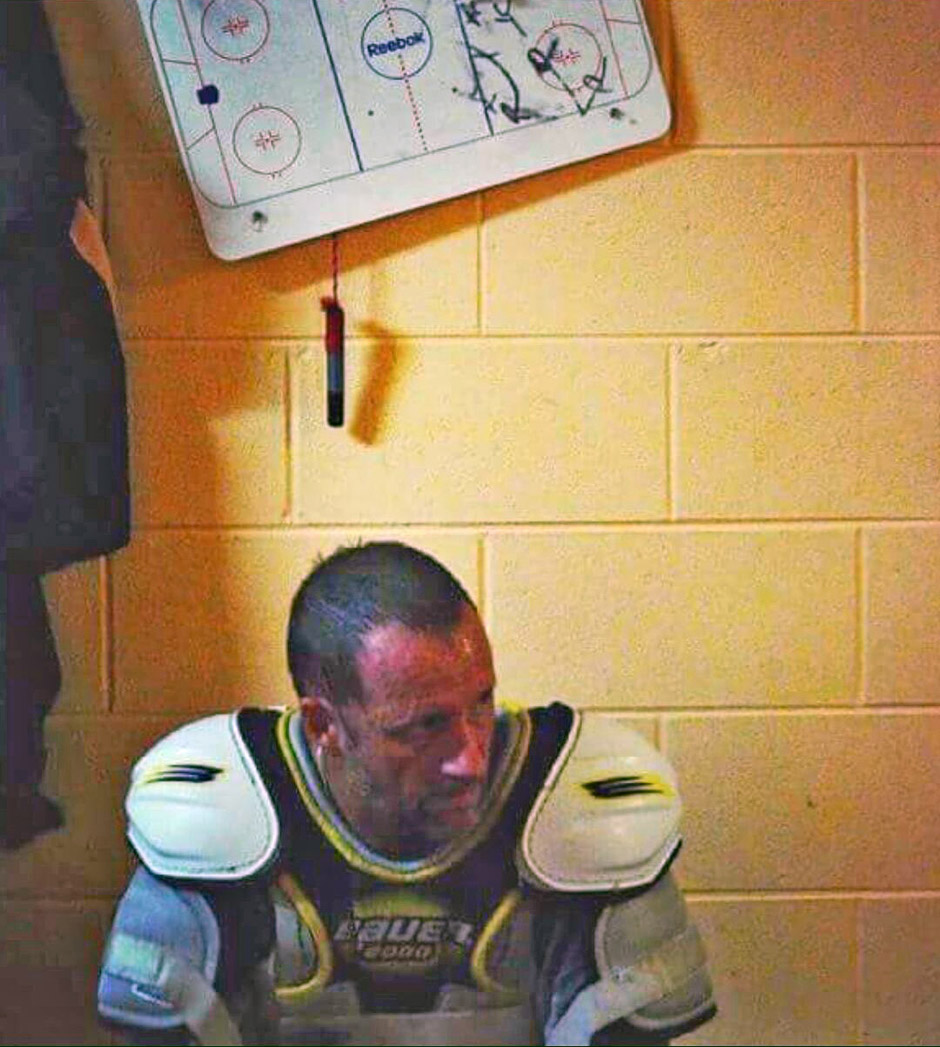

"The old saying, two bulls come out to play. Most times you went into a corner, you got hit or gave one". [12]

Killer

Kevin Price and the first rule of ice hockey

![]() The major problem that's occurred now in the National League, even though it is restricted to six imports per franchise, is that the local player — the Australian-born and developed player — has been "played out" of contention on some of the teams. The calibre has increased so dramatically over the past two seasons that, over and above the imports, most of the remaining players are overseas players who qualify as "local" players under the Federation's ruling (resident in Australia for 18 months continuously) or are now holding Australian citizenship. It's causing some concern in some circles, particularly NSW, and it's a problem we'll have to resolve before next season.

The major problem that's occurred now in the National League, even though it is restricted to six imports per franchise, is that the local player — the Australian-born and developed player — has been "played out" of contention on some of the teams. The calibre has increased so dramatically over the past two seasons that, over and above the imports, most of the remaining players are overseas players who qualify as "local" players under the Federation's ruling (resident in Australia for 18 months continuously) or are now holding Australian citizenship. It's causing some concern in some circles, particularly NSW, and it's a problem we'll have to resolve before next season.

![]() The position was changed immediately... We immediately appointed the Victorian coaching director into the National Coaching Director's position. Then we introduced National Coaches' Accreditation courses. Then we appointed a National Referee-In-Chief to lift refereeing standards.

— Sandi Logan, secretary of the national ice hockey association, speaking about the dearth of junior development, Sydney, 1980. [3]

The position was changed immediately... We immediately appointed the Victorian coaching director into the National Coaching Director's position. Then we introduced National Coaches' Accreditation courses. Then we appointed a National Referee-In-Chief to lift refereeing standards.

— Sandi Logan, secretary of the national ice hockey association, speaking about the dearth of junior development, Sydney, 1980. [3]

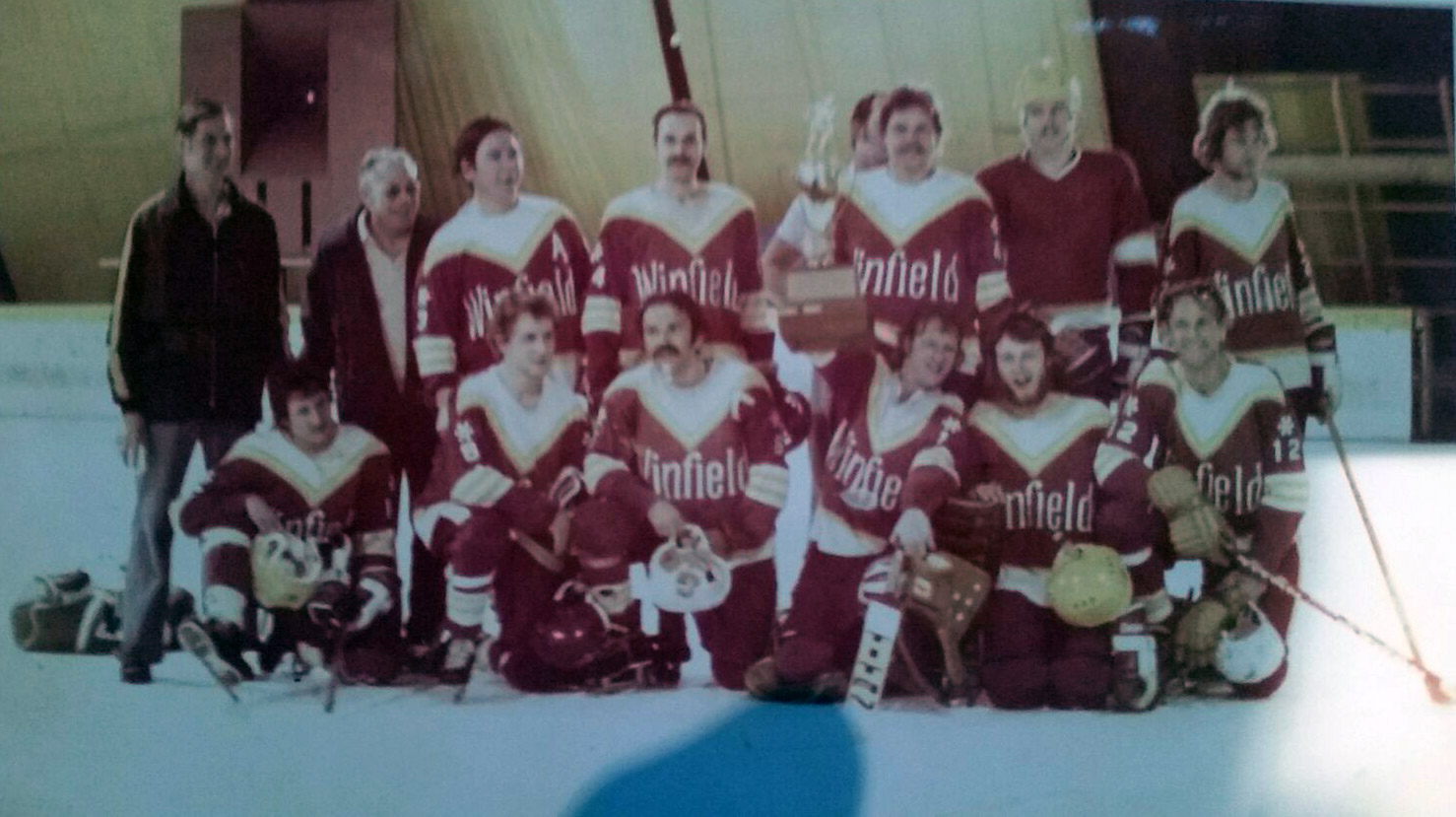

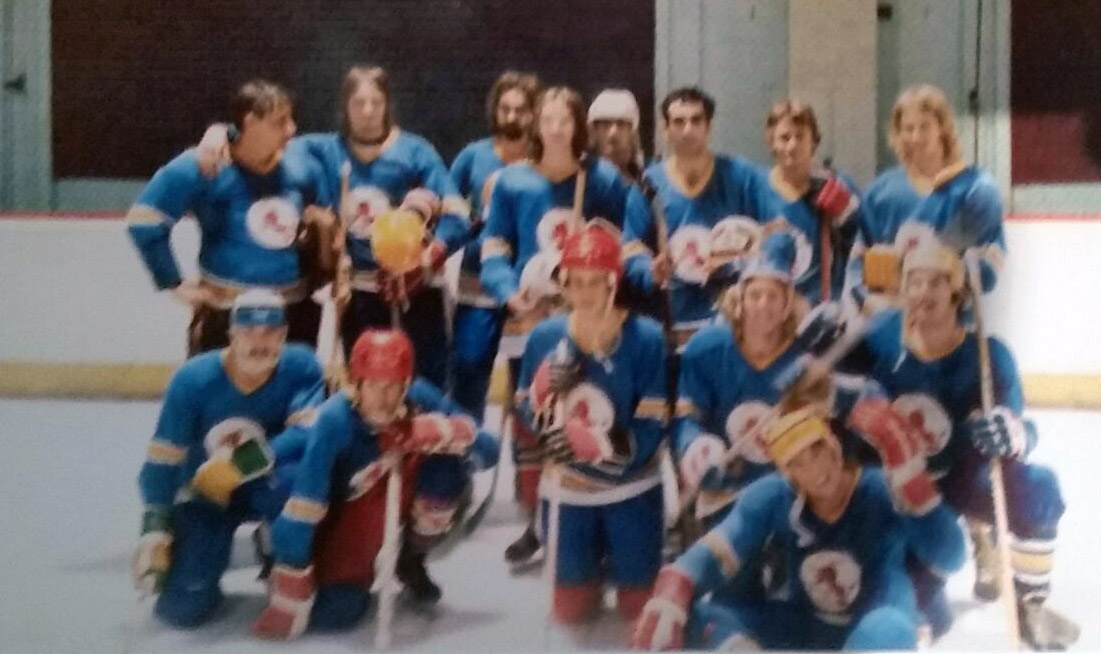

With the revitalised United International team, tryouts at Canterbury, 1980. [1]

With the revitalised United International team, tryouts at Canterbury, 1980. [1]

EVEN WHEN HE WAS FEELING WARM, the temperature in the bar where Price worked could drop away, the motion in his vision could slow to a crawl. "You asked nicely," said the demon in his head, "Very nicely". Holding the face of the over-sized drunk in the crook of his arm, he ignored the arms and legs flailing in the booze-laden air, and instead worked his way to the entry door, concentrating hard on avoiding the puke-inducing vapours, the assorted bodily fluids, and the vile descriptions of his mother escaping from the half-pickled weasel in his grip. "You can't bash him with your knuckles," reasoned the voice, "bash him with your free elbow until he falls through your arm into a heap at your feet".

"Welcome Back to the Icemen's Own Larry Holmes" announced the title of the newsletter article. "Kevin 'Killer' Price has missed the last few practices and games due to the trials and tribulations attached to his job. It seems a patron of the bar where Kevin works was asked nicely to leave a number of times, but refused. It was left up to Kevin to convince the 8-foot giant to never darken the door again... and the fun began. The Killer's lethal right cross finally decided the issue, but in the process the golden hand was severely cut and bruised. Stitches were given and then the hand became infected and swelled up to the size of a ripe grapefruit... in the meantime Kevin is working hard to improve his left hook". [2]

A Baby Boomer born on the cusp of Generation Y — June 27th 1959 at Canterbury Hospital in Sydney — Price started ice skating at 8 or 9. Like many ice athletes of his generation, he practiced figures and speed skating before he found his way into ice hockey at the Prince Alfred Park ice rink. Within just two seasons, he moved from development to the A-grade at the new Canterbury United club with Noel Taylor and Mark Stephenson, where he was knocked-out cold in the first game.

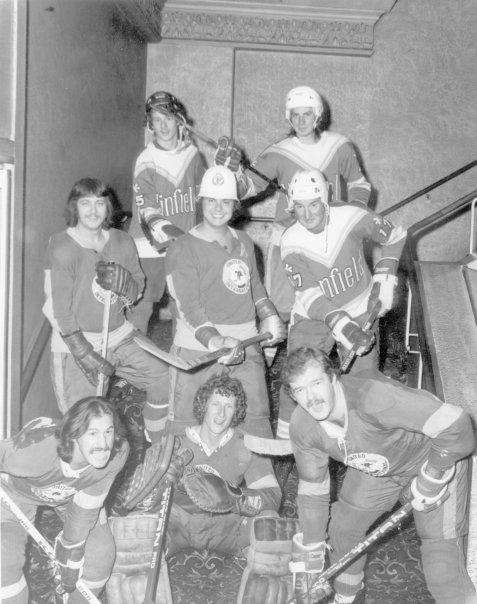

In the 1970s, he played for the Canterbury Viscounts, sponsored by Viscount caravans, and the Winfield Lions, [24] around the time they picked up a sponsorship with the Winfield cigarette company. [12] Glebe Lions continued their dominance of the five-team New South Wales state league during those years, briefly relocating to the new Blacktown ice rink around 1979-80. The association push for a club in the far western suburbs of Sydney using existing coaches and players did not pan out.

About fourteen players left with coaches Sandi Logan and Bill Lawther to train at Prince Alfred Park for a few weeks before moving to Canterbury. The club won only one game that season, defeating Newcastle North Stars, 1-0, at Canterbury, the lone goal scored by visiting guest, Adam McGuinness. [23] The death knell of the Lions was sounded by their own state association. The "one club one rink" policy left no other option but to disband because Canterbury-Bankstown were there first. [8] The Lions merged with Canterbury.

Blacktown went on to form its own club, complete with imported players and coaches, including Canadian ice hockey ambassador, Mark Sadgrove, a very strong junior program, and Price as both player and coach. Amid the gender controversies of those years, Price encouraged and supported the first women returning to the sport, an interest to which he would later return.

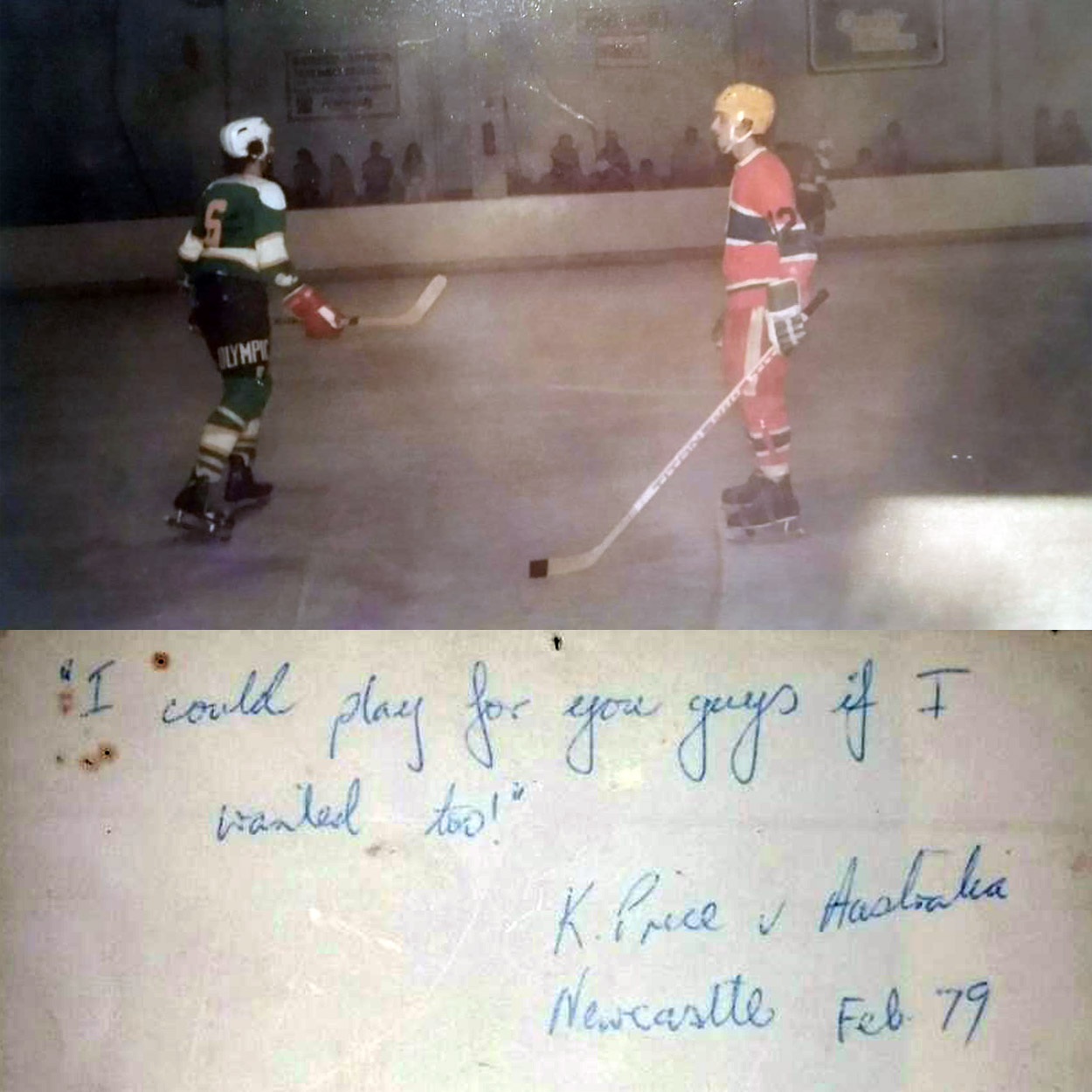

In 1979, he played for the Newcastle All-Stars against the Australian National Senior Team, and in Dick Mann's breakaway league at Newcastle. He joined the Finn Eagles, "99 percent" composed of Finns, before returning to Canterbury, and representing his state in both the Brown Trophy and the Goodall Cup. He won the 1979 Brown and the 1983 Goodall. [12]

IT TOOK TEN YEARS for Australian ice hockey to return to the world stage after the costly first forays of the 1960s. The 1960 Olympic and Worlds team was All-Australian, but three Canadians were picked for the country's second international, the 1962 World Championships in Colorado Springs USA. The IIHF ruled the Canadians ineligible to play and so Australia's second international squad was also All-Australian. It produced the nation's first international win, a remarkable 6-2 defeat of Denmark.

Elgin Luke, Charlie Grandy and Phil Hall were not the first overseas born and developed players chosen to represent Australia, but they were the first to actually compete. All three arrived together in their early twenties in 1962, and made the cut the next year for the 1963-4 Olympic Qualification team in Japan. Australia failed to qualify against the ninth-ranked nation in the world, an outcome that was all but pre-ordained in the OIC-IIHF decision to qualify only one country from the region.

Many nations do not support players developed elsewhere on National Teams, and it is doubtful imported players improve the skills of locals in the few weeks Australia prepares for international ice hockey competition. That is the responsibilty of a sport's national body and its national leagues. Most player development occurs through more and more structured practice and higher competition.

Understandably, many locals here feel disadvantaged by the stopgap use of overseas players with less potential than young locals to become top players and represent their country. That is usually the case with overseas players who are past their prime. There is also an obvious difference between overseas players rewarded with incentives to play hockey in a top national league, and players who naturally migrate at a young age, become locals, and pay to learn and play.

Imports developed in better overseas leagues provide quick injections of skills and experience. Employed astutely, such as marquee players in a national league, players with more skills and experience can raise league quality, creating the higher competition that can lead to the improvement of local players. Employed poorly or overused, they can arrest the development of prospective national team players. Locals left with under-developed potential like that, must then learn to deal with the extra mental challenges of never being quite good enough.

Luke, Grandy and Hall became Australians and helped develop the game long after their playing careers were over. In his thirties, Phil Hall was Alternate Captain of Australia in the 1964 Olympic qualification team. At 34, Charlie Grandy was Captain of Australia in 1974, and again in 1979, at 39. Yet, on the other hand, some top Australian-born and developed players missed out on a spot in these squads due to mismanagement. [9] Others could not afford the hefty costs to compete.

Appointed Coach of the 1974 Worlds team, Elgin Luke replaced eight locals in the All-Australian format with eight players born and developed overseas. Only two-thirds of the 22-member Australian Men's National Ice Hockey Team was born and developed in Australia. They were everybody's favourites, but despite the large overseas contingent, they won only one of seven games, defeating North Korea, 4-1. Luke's squad played teams ranked fifteen to twenty in the world — Hungary, Switzerland, China, France, Italy, Bulgaria. Yet, some branded his squad and the 1979 Worlds team that followed as grand ideas but dismal failures. [3]

Voted best-dressed in 1979, Team Australia did not win a single game against nations ranked 19 to 25 in the world — Yugoslavia, Italy, France, Bulgaria, Britain, Spain and South Korea. Canadian player-turned-coach, Dan Reynolds, kept Luke's format — two-thirds Australian, one-third overseas. The promising young nineteen year-old named Kevin Price was not among them, although Reynolds did choose three others who were about the same age — Kris Pike from New South Wales, David Lindsay from Queensland and Victoria's John Ekberg, the son of 1960 Olympian, Vic Ekberg.

Australia's performance in Barcelona was more disappointing than five years earlier in Grenoble, and no longer could it be blamed wholly on under-developed locals. The nation dropped from ninth in the 1960 IIHF World Rankings to 26th in 1979, and it was not invited back to the IIHF Championships until 1986. Something was wrong. More than a few imported players detected it immediately on arrival and argued for a greater investment in the obvious potential of young locals. But they were ignored for a long time until the national league, and some of the local ones, came to be dominated by whole teams of imported players. That was when the Ginsberg-Logan administration were pressured to act. [3]

Junior development was all but non-existent in some states, and elsewhere it was neglected by all but a few. Victoria had only just appointed a State Coaching Director, a situation some in New South Wales liked to attribute to the greater number of ice rinks, resources, coaches and players down south. [3] In fact, it was not like that. New South Wales had more ice than Victoria and comparable resources. Although ice rinks closed at Canterbury in 1969 and Burwood in 1970, Canterbury II opened in 1971, and others operated at Prince Alfred Park and Narrabeen. Blacktown (1979) and the Macquarie Centre (1981) followed later. Ice rinks also opened, closed and reopened in Canberra and Newcastle, both active parts of the state ice hockey scene.

In Victoria, three rinks also operated through the Seventies at St Kilda, Oakleigh and Ringwood. Two more opened later at Dandenong (1977) and Footscray (1979), all but one of the five collapsing like a house of cards from the early Eighties, starting with the state's flagship, St Moritz. Logan described the top NSW competition hockey of the time as "beer league", [13] funded mainly by sponsorships from pubs and tobacco companies, much like Canadian senior ice hockey. "No top level to speak of," recalls Price. "...Fun and fights. Ouch!" [12]

A similar culture also thrived in Victoria in the Seventies, but something else was also afoot in Melbourne. "... The game needed and needs professional thinking and administration," said rink developer Pat Burley in July 1979. "It is only just getting it now". He organised local rink owners into an Association with more clout than all the state and national controlling authorities combined. He also set up the Burley Cup that year, a sanctioned state league separate to the Victorian league.

Coincidently, Elgin Luke initiated the first VIHDC Development Council in Victoria, an organisation and spirit that would one day evolve into a veritable production line of fiercely trained juniors. For a time at least, future juniors would grow-up believing they were a red, white and blue bloodline, the rightful heirs to the kingdom of hockey, even when they were completely out-classed. Many young players in this system devoted their adolescence and most of their childhood to an extraordinarily expensive coming of age on the world stage. Or so they believed.

In his role as state Coaching Director, Luke was the primary initiator and planner of VIHDC programs designed to improve players, coaches, referees, off-ice officials and trainers. The program was snapped-up by a national association led by Phil Ginsberg and Sandi Logan, and Luke was later appointed national Coaching Director in 1981. He continued coaching over the next ten years.

The World Juniors, the IIHF world championships for players under the age of twenty, officially began in 1977, but it took Australia until 1983 to first compete, by which time Price and his age band were ineligible. The nation did not attend the Youth Worlds until 2002, although Australians competed in all but five of the IIHF Asian Oceanic Under-18 Championships, from the time of the first tournament in 1984.

Australia's decline in the IIHF World Rankings continued into the early 1990s. The task of arresting it was left to another Canadian-born coach named Ryan Switzer and Generation X. These young Australians were born just after Price in the 1960s and early 70s. [11] They were the first edition of the junior player development system introduced in the Ginsberg-Logan era, the first athletes of the national junior development council. By that time, Kevin Price's junior ice hockey career had finished.

When Tom Wolfe dubbed the 1970s the "Me" decade, [10] he referred to the rise of a culture of narcissism among the younger generation of an era ruled by discos and nightclubs. Among the many young people like Price who took up the sport in those years, were many who eventually just dropped out. Disappointed and weary of watching lesser lights or imported players advanced ahead of them, they were the casualties of an amateur club system that was seemingly incapable of remaining focused on the development of top player potential. It was a long course, 10 or 15 years, in which the only constants were the most committed of young players with cash.

"I was a rookie at PA playing for Winfield Lions," recalls Price. "A fight broke out, I was on the bench. I said to the Manager, 'Elbow' Cameron (Harry), 'What should I do?' 'This...' he said, and leaned over the boards, grabbed Allan Harvey, the vice-captain of Australia who I looked up to, then started to pound on him". [12]

"An eye for an eye" went the mantra of most coaches, "win at any cost" was another, even in the youngest grades, and it is doubtful a consistent development model applied over the long junior careers of any of their young players. Even if it did, it mattered not, because the system was often undermined, and not least by some of the parents of young players who worked themselves from the stands to the bench, to positions of influence or authority, to the heavily guarded inner sanctum controlling the sport's precious resources.

Large parts of this system operated as an old boys club, complete with a slightly shady code of silence. What happened on the ice, stayed on the ice, for fear of retribution. This is not unique to ice hockey. Manipulation occurs in other sports too, but its negative effects are more disadvantaging in minor sports, especially those with an exceedingly high cost of participation. There is a lot to lose in any system where the power over access to opportunity is concentrated in the hands of the few, especially when they have conflicting interests. But the stakes are even higher in Australia because access to ice surfaces for sport is very limited, very costly.

By the mid-Seventies, each Australian in the country's binge drinking culture consumed an average 13.1 litres of pure alcohol, about one-third more than today, and three-quarters of it was from beer. The Olympic heroics of the early 1960s were all but buried in the suburban backyards of Melbourne and Sydney beneath piles of crushed tinnies. During these years, clubs on the eastern seaboard found a new sense of belonging, transforming themselves from proudly Australian sporting institutions, however overlooked, into a kowtowing branch network of the Canadian senior hockey league.

In later years, the names appearing on club perpetual trophies were the sons of organisers or coaches' favourites, descending however inappropriately in direct lineage to revered ice athletes from as far back as the war. The player awards system made a handy bargaining currency among mates in a game of false machismo and one-upmanship, all of it well lubricated by slab after slab of frothies. If you're not one-up, you're one-down, when you're gaming the system. Authentic athletic prowess could now be trumped by the longer lines of fine "clubmen" or their relos, emerging often paralytic from a foaming, liquid amber haze.

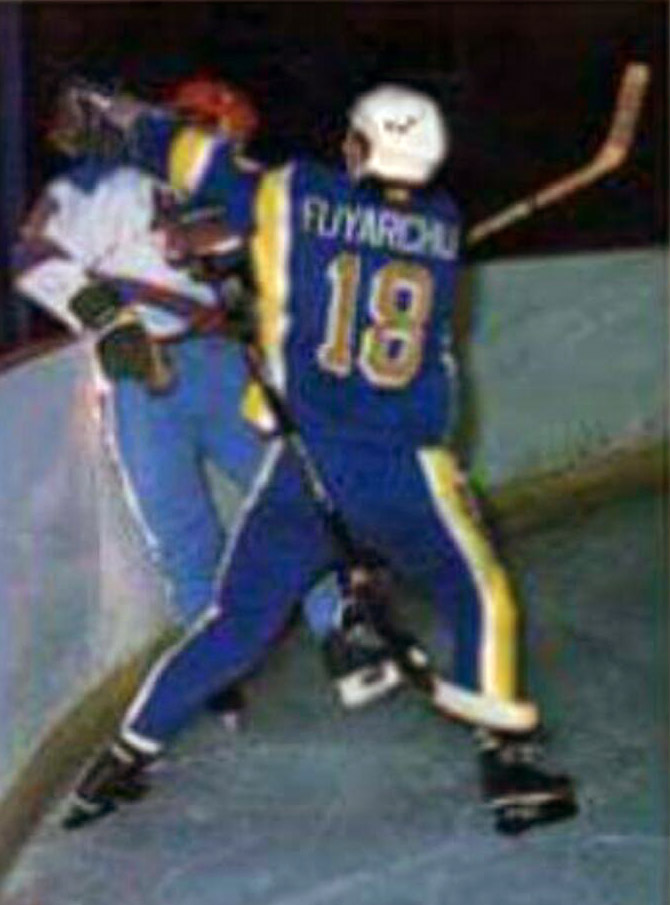

LUKE'S JUNIOR DEVELOPMENT SYSTEM, the VIHDC, started up in Victoria in 1979, the same year as the Burley Cup, but it was a Burley Cup spin-off that raised the VIHDC to national level in an unintended way. The sanctioned National Ice Hockey League, organised by the Burley-led Australian Rink Operators Association, restricted each team to six imports, but in its first season in 1980 the Australian-born and developed player was "played out" of contention on some of the teams, especially in New South Wales and South Australia. Ask Kevin Price about that and he will probably shrug and say, "I was part of it". [12] Almost forty years on, Canadian import Dan "Cowboy" Pedersen remembered Killer as a very good skater.

One of three Australian-born players chosen for the City of Sydney All-Stars in the new League in 1980, Price joined locals Noel Taylor and Michael Solomon in the otherwise imported line-up coached by Gordon Bettes, managed by John Kendall-Baker and trained by Sub Majsay. As the name suggests, the All Stars were purportedly the best available players from all of Sydney's clubs and the city's only NIHL team.

In stark contrast, Melbourne iced four NIHL teams, some of which were almost All-Australian. Not because they had more rinks, they didn't, and not because of their Development Council, it had only just begun. There were more teams with more local players because of the professionalism brought to the sport by Burley and, a little later on, his association of rink operators.

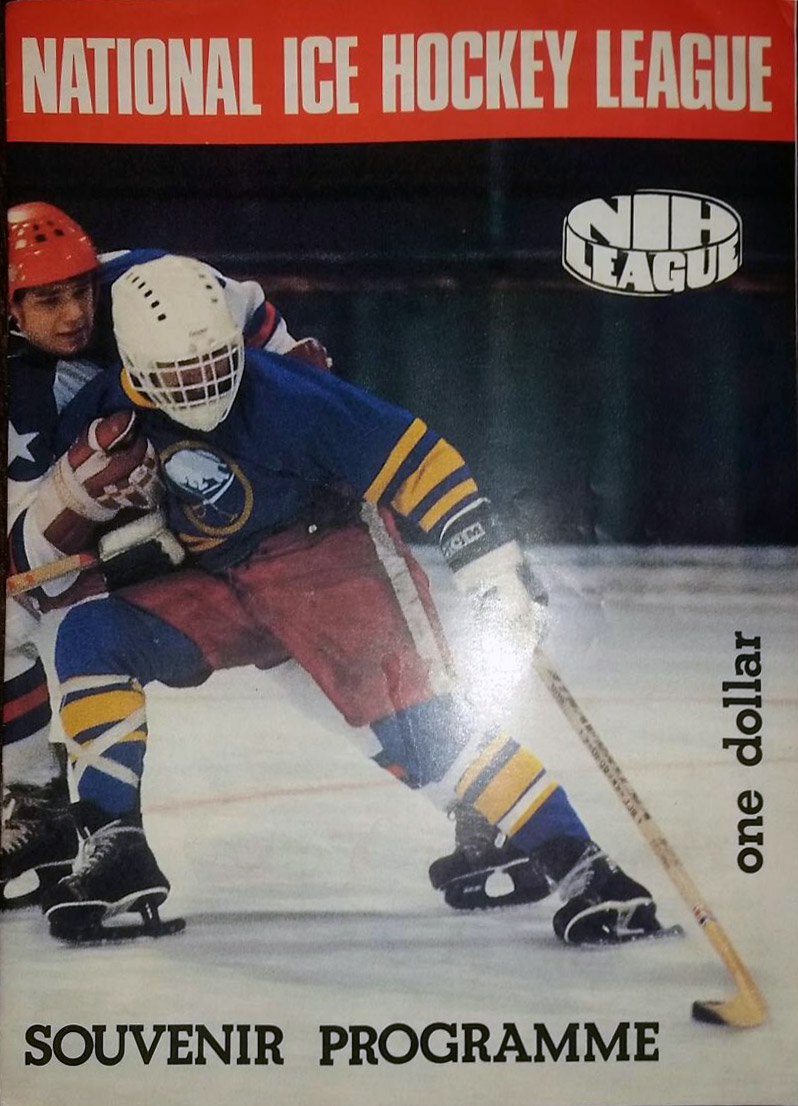

Simply put, there was more Burley in Melbourne. He knew the ropes, he ran three of the city's rinks, players loved his approach, and the paying crowds loved the players. He was onto something. The round robin of forty-two home and away games ran over fourteen weeks, costing each of seven teams up to $15,000 for cross-country flights, overnight accommodation and equipment. [3, 14]

The road to the best-of-three finals series pitched Price's club against Newcastle in the semi-finals. Earlier in the round robin, the All Stars met the North Stars with mixed success, beating them 10-2, and then succumbing to them, 4-6. Sydney finished first in the standings on a plus-55 ratio of goals scored for and against, but it seemed they were beatable. Newcastle's last-minute bid from fourth spot was enough to make the semis. Before 750 partisan supporters, Price and the All Stars battled to a 5-5 draw in the opening game on the smaller Newcastle ice, where an unfortunate accident cost them their South Korean national team player, Chul-Ho Kim.

In the second game in Sydney, the referee handed out a game misconduct, two ten-minute misconducts, and four five-minute major penalties. "There are two ways of getting the puck off a man," said George Allan that year, a Canadian who had lived in Sydney's Blacktown for the past five years. "You can take it away from him, or you can take him away from it. We're taught to take the man away from the puck. It works most of the time". [15]

North Stars goalie, John Heggie, faced seventy shots allowing four goals, while Burke Thornton, the All Stars netminder, swept aside forty-two of forty-four shots. All Stars captain and Man-of-the-Match, George Kenning, was the inspiration behind Sydney's 4-2 win, scoring twice and assisting on a third goal. [3] Kenning won the 1975 John Nicholas Trophy five seasons earlier, the Goodall Cup MVP. Sydney's prolific scorer, Centreman Darrell McDonald, managed two assists.

The All Stars also won the last game of the Northern Division semis, 5-1, against a disconsolate Newcastle coached by Dick Mann. At last they were through to the Grand Final against the Ringwood Rangers from Melbourne or, perhaps more to the point, against Pat Burley. [3] The Rangers managed by Burley, were almost an All-Australian team who finished the season in second place on plus-17.

Their road to the grand final went via the tough, hard-hitting Oakleigh Aces, managed by Graham Argue. The Aces won the first game 8-3 at home on the small ice of the Olympic Ice Skating Centre at Oakleigh, but dropped the second, 4-3, in a much closer contest on the big ice of Ringwood Iceland. [3]

"We knew they could probably hit us out of the rink if they put muscle into their play all the time," said Burley, "but we realised their play would suffer as a result. We copied their approach and it worked". [3] The decider was a 1-1 tie, right up until the start of the final period, then mid-way the Rangers made it 2-1, and held on to the lead until the final whistle. [3]

Sydney won the first game 5-0 against the Rangers, but it was not all easy going. The All Stars played at least one man short for eleven-minutes, and two men short for part of that, but as Sandi Logan recorded it, the Rangers had real difficulty breaking through the skating defense of Dan Pedersen, George Kenning and Logan himself. When they did, Sydney's netminder, Burke Thornton, brushed them aside.

"In my home town, Saturday night hockey was the big event of the week," said Thornton in a Pix-People magazine interview in 1979, "and everybody would bring a case of beer down to the rink". Everybody also read this magazine at the height of its popularity during the 60s and 70s. "They didn't care who won the game as long as the home team won the fights". [15]

Did the line just blur? Was this recreational hockey or top-level competition? "Back then, the 2-line pass was still in," recalls Price. "It still should be for player safety. Every shift you got or gave a big hit in the end. The old saying, two bulls come out to play. Most times you went into a corner, you got hit or gave one".

Neither macho culture nor alcohol hijacks your moral compass. They are just symbols that give people a social license to behave in an uninhibited way, but they do have a tendency to linger on. Even today, it is not uncommon for some local A-grade clubs to sacrifice development of young players so others well past retirement age can continue their race to accumulate Most Games. Yes, they pay the same money, but is that all that we want from our top leagues?

In the second Finals game in Sydney, with "all the trappings of grand final pageantry," [3] referee Igor Sedivy handed out 144 minutes of penalties. George Kenning scored unassisted and then set up Bobby Brown. The Rangers replied through Malcolm Heath, then Sandy Gardner, both goals assisted by Dave Fehily. The second was also tit for tat, with goals to the All Stars (McDonald from Logan, Glen from McDonald) and the Rangers (Heath from Walker, Kinnunen from John), tying up the score once again, 4-4.

Then, in the deciding period, Sydney blitzed the southerners, putting up five unanswered goals as they raced to an almost unassailable lead. Bob Brown scored a hat-trick inviting his frustrated opponents into silly penalties, including a delay of game against the Rangers' bench. The All Stars' goalie faced only 14 shots for 4 goals. Price's team won the inaugural NIHL season from their Burley-operated Iceland at Prince Alfred Park with their pick of the best available from Sydney and overseas leagues.

Involved with League promotions on the Mike Walsh Show and elsewhere, Price continued with the Club when Sydney iced a second team, the Warringah Bombers, in the 1981 NIHL expansion. The Bombers won that season with a team much like the Sydney All Stars. It was the last of the NIHL, and the Sydney Icemen formed on the eve of the inaugural state Super League. A product of the demise of the Finn Eagles and St George the previous season, the Icemen were one of three new League teams with others from Newcastle and Canberra.

Price was capable of rallying his teams, as he did with the Icemen against the Knights in 1982, leveling the game 3-3 through Tim Sorely and Craig Montgomery after being down 2 goals. [5] After sixteen games that season, he was club top scorer on 7 goals 6 assists, and the most penalised on an average three minutes per game. Then in 1983, he won the Goodall Cup, the national championship, representing New South Wales, and entered the live-televised Slapshot series with the Icemen.

After his Bouncer career, Price went on to Management in local hotels. Fully accredited, he coached boys teams at Blacktown and was one of the Canterbury United players who supported Wendy Ovenden and Annette Davis, the first Sydney girls to play when women's ice hockey resumed at Canterbury in the early Eighties.

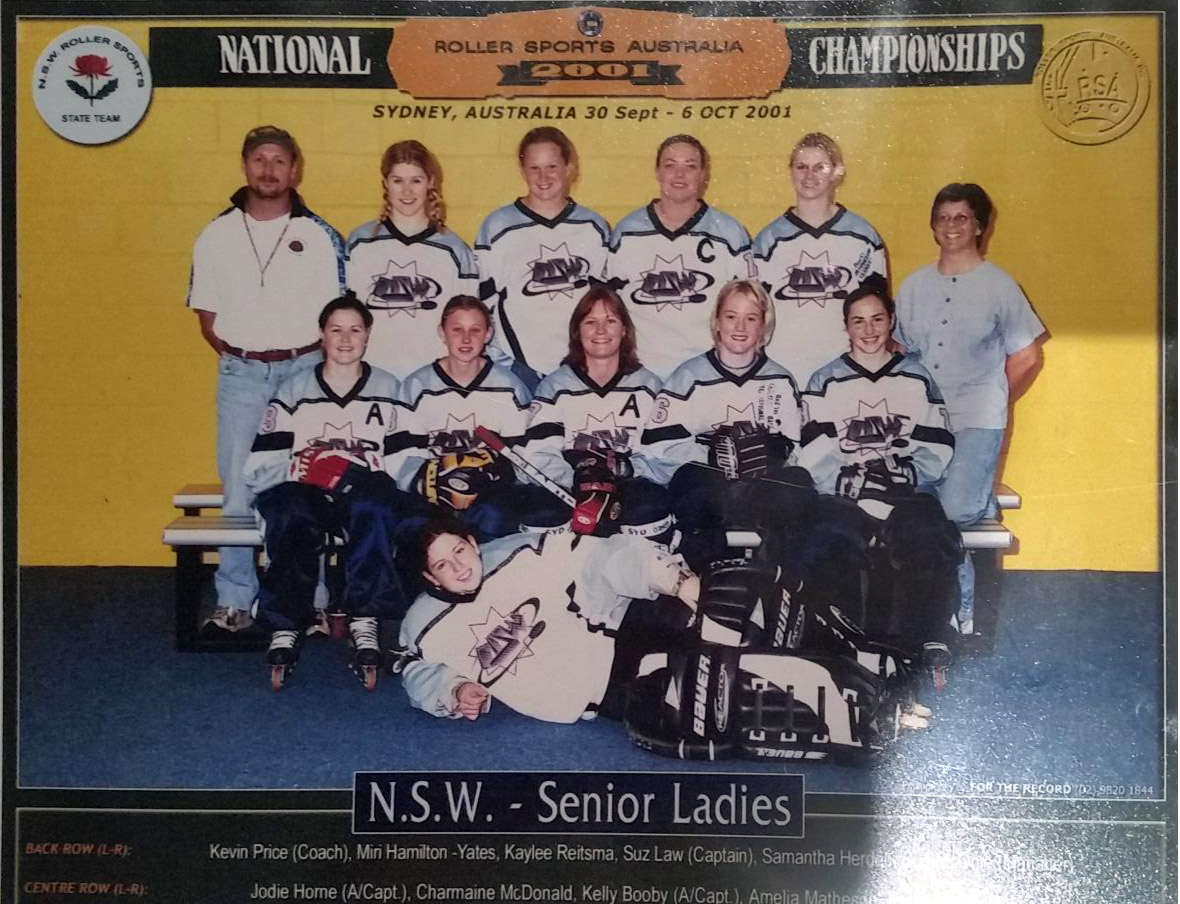

He continued coaching boys and girls teams at Canterbury for over thirty years, right until the time of writing, and ran ice and inline camps all over New South Wales. He operated an inline hockey school at Skate Central at Gosford from the late 1990s, coached state inline hockey teams, and represented Australia against Kuwait and New Zealand in the Asian Oceanic tournaments.

Retiring from playing when he married in the early 1990s, he moved to the Central Coast and worked as General Manager of the Erina Ice Rink. He helped set up the Cyclones Ice hockey Club on behalf of the rink, with Craig Air and Allan Harvey, and a successful Development Academy attended by up to one hundred youngsters at a time. He coached the Midgets (U15), the Erina Cyclones and the women's Cyclones to state premierships.

A state women's team coach in national competition from around 2005, he led the NSW women to victory in the 2010 Joan McKowen Trophy. His own game resumed with the Central Coast Brewers and in 2017 he still played old-timers hockey with the Stiff Breeze, or "Stiffys", an Over-35 masters team with a name derived from the local Cyclones. His son James and daughter Karla both played hockey for the Cyclones. Kevin Price celebrated the 50th anniversary of his ice hockey career in 2018.

Killer's family could not afford the cost of representing Australia overseas, but he did represent his country against a visiting Canadian Navy team and at inline hockey. A photo of Price in club uniform, with a player from the National Men's Ice Hockey Team, has a note on the back which says: "I could play with you guys if I wanted to. K Price v Australia, Newcastle, February 79".

Coaching ambition, Sydney, undated. [12]

[1] Top Teen in Sport No 14, Ice Hockey Champion, The Australian Women's Weekly, 31 Jul 1963.

[2] Sydney Icemen newsletter, undated.

[3] Powderhound ski magazine, 4 Dec 1980.

[4] Puck Happy, James Franceschini, People magazine, 1980

[5] Knights hold on to break the Icemen, The Canberra Times, 3 Aug 1982

[6] Canberra Knights will play in Super League, Barry Rollings, The Canberra Times, 1 Jun 1985

[7] The Icemen cool the Knights, Sydney Icemen newsletter, undated.

[8] Glaciarium Ice Hockey Club Minutes, in "Ice Hockey: the NSW Ice Hockey Association Inc Australia — Facts and Events, 1907-1999" by Syd Tange, NSW association, Sydney, 1999.

[9] For example Tony Martyr and others considered Keith Jose was omitted from the 1960 Olympic Team due to mismanagement.

[10] "Tom Wolfe on the 'Me' Decade in America", August 23 1976, New York Magazine, NY USA.

[11] In Australia, research found that the Boomer parents of Gen Xers were "the most divorced generation in Australian history". See for example The Generation Map, McCrindle Research Centre, article in the ABC of XYZ, understanding the global generations, Mark McCrindle Sydney UNSW Press, 2014.

[12] Biographical notes from conversation with Kevin Price, January 2018.

[13] The Windsor Star, Windsor Ontario, Canada, 25 Jun 1980, p 20. Australians learn about hockey, thanks to enterprising Canadian.

[14] National Ice Hockey League 1980 Fixture

[15] "Aggro on ice" article, Paul Mann, Pix People magazine, Sydney, c1980.

[16] The Lions club was the oldest in the League, tracing its origin back to 1923 when it applied for affiliation to compete in the 1924 state league as Central Ice Hockey Club. [8] In the years when players had to reside in the district and compete in district colours, Glebe played in maroon, the colour of the local rugby league club. The average age of players was 18.

[17] Glebe became Glebe Lions during the Forties when asked by rink management to adopt names with more appeal, and in 1951 "Glebe" was dropped and they were known simply as the "Lions" in new colours of black and gold. [8] Harry Cameron played for the club in the years before Sydney Glaciarium closed in 1955. He took his nephew Wayne Brown skating there and later inspired his interest in ice hockey.

[18] When the game was revived in 1959 with the opening of the open air rink at Prince Alfred Park, Cameron's nephew Wayne was a member of the reformed club that won back-to-back state premierships in 1962 and 1963, and the 1962 Australian Club Championship against the Blackhawks, the Victorian champions. Some of the team were invited to compete in the Olympic Qualification Team in Japan in 1963, but they could not raise the money.

[19] Cameron was made a Life Member of the state association in 1964 and awarded the Hudson Trophy in 1969, a national association award recognizing "unselfish and sustained efforts in furthering the aims of ice hockey in Australia". Among the Club's other notable players and coaches were goalie Jim Barnett from the start, Roy Philpot from the 40s, and Ken Kennedy who transferred from Easts.

[20] Teams of the inaugural NIHL in 1980 were Ringwood, Footscray, Oakleigh, Dandenong from Victoria; Newcastle, Sydney from New South Wales; and Adelaide from South Australia. The Grand Final program was dated Sunday, September 7th 1980.

[21] The home ice of the Sydney City All-Stars was Prince Alfred Park Iceland, which at that time was operated by Pat Burley, owner-operator of the Iceland rinks at Ringwood and Footscray in Melbourne. The team captain, George Kenning, was a 32 year-old computer analyst who first came to Australia in 1973, and represented and captained the state on numerous occasions. Goalie Burke Thornton arrived from Canada in 1978, joined St George and represented NSW in 1979.

[21 cont...] Others on the team were Noel Taylor (5), Dieter Hoch (12), Michael Soloman (18), Dan "Cowboy" Pedersen (4), Canadian goalie Burke Thornton (30), John Loden (6), Peter Aitken (back-up goalie) (1), Jim Hoar (2), Sandi Logan (3), Peter Gwozdecky (8), Bobby Brown (9), John Glen (10), Ralmo Karlsson (13), Wally Dahl (14), Kevin Price (15) and Darrell McDonald (16). Coach Gordon Bettes, Manager John Kendall Baker. Trainer Sub Majsay.

[22] The Ringwood Rangers based at Ringwood Iceland were: Tim Murphy (G), John Walker, Helmut John, Greg Wanden, Chane Barber, Sandy Gardner (C), John Batson, Trevor Gardner, Ron Sullivan, Malcolm Heath, Tim Walikainen, Johann Kinnunen, Graham Heath, John Ekberg. General Manager Pat Burley. Manager Ron Law. Coach Malcolm Heath. Trainer Bruce Jamieson.

[23] Lions historical snippets from Sandi Logan and Brett Morgan, Legends Facebook, 2017.

[24] The jersey of the Winfield Lions, a later edition of the Glebe Lions, was a direct copy of the Winfield cigarette packaging comedian Paul Hogan promoted, from a time when tobacco sponsorship had a free hand.

[25] Canterbury formed at Bankstown in 1969, changed name to Canterbury United International in 1971, and are known today as Canterbury Eagles.