AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL MEN'S TEAM, HOTEL SOMEPLACE, PERHAPS HULL ENGLAND, 1992, OR LJUBLJANA SLOVENIA, 1993. [8] [21 IMAGES BELOW]

The Soul of a New Team

Ryan Switzer and the greater game

![]() Cumulative advantage as a team, not individuals, played a big role in their success in an extremely tough competitive era, given the high quality of opposing teams unique to this time.

— Ryan Switzer, Sydney, June 2018. [1]

Cumulative advantage as a team, not individuals, played a big role in their success in an extremely tough competitive era, given the high quality of opposing teams unique to this time.

— Ryan Switzer, Sydney, June 2018. [1]

![]() From my perspective coaching leadership played a key role, always a pleasure playing under Ryan Switzer.

— Rad Benicky, former player, Australian National Men's Team, Sydney, June 2018. [1]

From my perspective coaching leadership played a key role, always a pleasure playing under Ryan Switzer.

— Rad Benicky, former player, Australian National Men's Team, Sydney, June 2018. [1]

![]() Synergy is what happens when one plus one equals ten or a hundred or even a thousand! It's the profound result when two or more respectful human beings determine to go beyond their preconceived ideas to meet a great challenge.

— Stephen Covey, American author and educator. [2]

Synergy is what happens when one plus one equals ten or a hundred or even a thousand! It's the profound result when two or more respectful human beings determine to go beyond their preconceived ideas to meet a great challenge.

— Stephen Covey, American author and educator. [2]

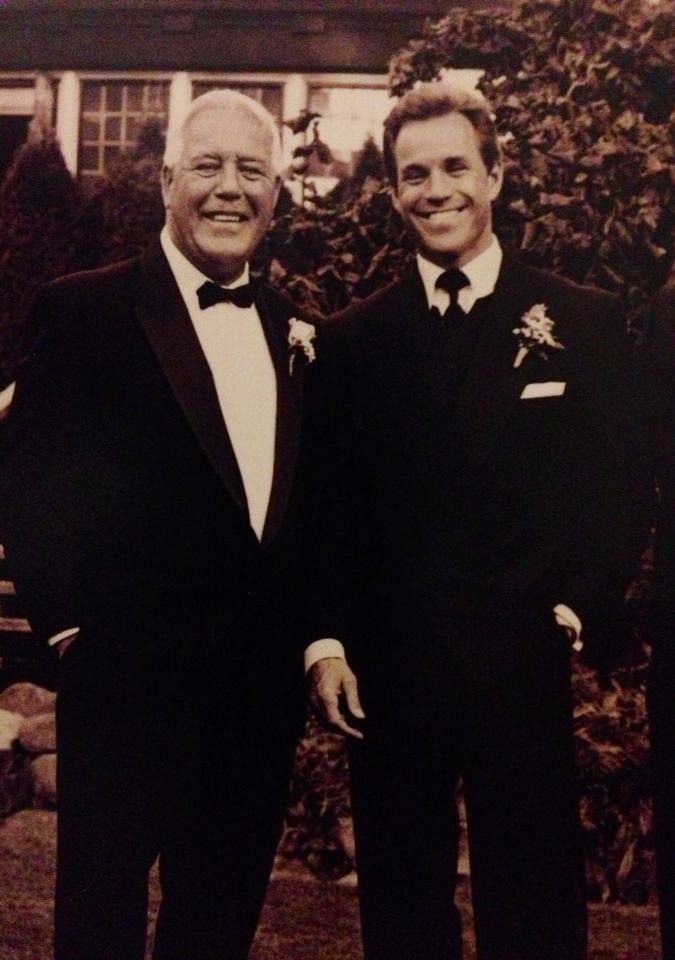

Don (left) and Ryan Switzer, Ryan's wedding, undated. [8]

Don (left) and Ryan Switzer, Ryan's wedding, undated. [8]

IN THEORY THEY SHOULD NOT BE WINNING, yet they are. Expressed as an equation, this is 6 x 1 > 6. A team of five skaters and a goalkeeper outperforming its best player of the game. Beyond 6 is the kingdom of gold where medals become reality. Teams need to create synergy like this at the top of each IIHF world championship division, but only a few do. And even fewer can do it consistently, let alone every time. It is harder in the game against the Division's top side, the side relegated the previous year, and an Olympic final is even harder than that. Yet, the best teams, the ones at the top, they either get close or they actually do it.

Out on the wet pavement, the big wheel is motionless, the side-shows empty, Coney Island rejects, a big-top no-one ventures. Australia twice broke through to Division 1 in recent times, but the nation Down Under is still under the glass ceiling of Division 2. Stranger still, it is a glass ceiling of their own making. Yes, they made their own cage. Because they rarely use synergy. That rare commodity Australian ice hockey needs, yet does not want. As ethereal as fairy dust, synergy is essential to extending the frontiers of Australia's understanding of the game, because anything less does not cut it at the top. Yet, we don't want it. We want Coney Island instead.

"I see in my team," says a young player approaching his prime, "some of the strongest and smartest locals who ever developed their game here. I see all this potential and I see squandering. An entire generation lugging four-by-twos, pulling drinks, making latte art, slaves in black helmets, hockey has us chasing money for others, working jobs we hate so we can pay to play at the next level. People pulling strings. Long-nosed puppets dancing".

In the Seventies and Eighties, hockey fans here mainly watched games where one or two players achieved great personal stats, but the team lost. In the 1974 Worlds, one or two locals did more body and stick checks than the rest of the team combined. Every game. In the games in which Australia scored in '79, more than half the team's goals were from one player. [3] No magic numbers, only obvious and measurable reasons. No team created something greater than the sum of its parts.

They allowed a player to work at a more personal level without the added support of the team, undermining the potential for synergy. Or maybe a player overstepped his role, creating more opportunities for himself, to push his stats up higher than the others. But even then, even when it was a great individual performance, it was not synergy, it was not teamwork. You have to commit to synergistic relationships. You need the will to engage that way with others first. Then every other player must get it. They must show an ability to engage.

"We're the lost generation," smiles the boy stripping armour. "No purpose, no place, we have no wage to fight for, no working conditions to protect, our war is a mental war with ourselves, and those who broke the faith. Our life's challenge is our game, the game we trained for since eight, raised by clubs to believe that one day we'd all be first liners and represent our country and play pro hockey, but we don't and we won't and we're slowly learning the fact, and we're very pissed off".

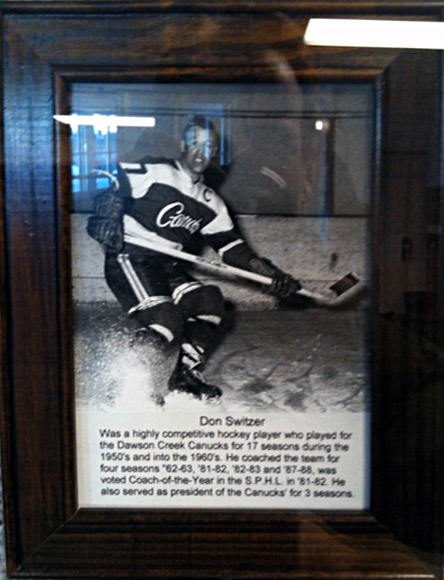

DON AND BARBRA'S SON RYAN was born August 16th 1960 at Dawson Creek BC in Canada. The Switzers were a huge hockey family, Don completely immersed at all levels, a player captain and coach for Dawson Creek Canucks Senior A, the 17+ age band, and a Western Canada scout for Philadelphia Flyers over 18 years. They were very athletic, Don and Barbra, very active and very fit. Their children grew up with hockey and Don also taught boxing, the boys putting in 20-minutes a night like kids who practice piano, but on a speed-bag Don installed in their basement. Its adjustable floor base allowed them to spar at the height of the next game's tough-guy fighter.

Don played for Dawson Creek Canucks for 17 seasons during the 1950s and into the 1960s. He coached the team for four seasons in the 60s and 80s and was voted SPHL Coach of the Year in 1981-2. He also served as president of the Canucks for three seasons. "Dad was never a yeller as a coach," recalls his son. "He was more cerebral in his approach, even though he was tough and very disciplined. 'It takes the same amount of time to win a game as it does to lose,' he'd say. 'So you guys let me know your decision before the game so we don’t waste each other's time'".

On the ice as a toddler at Dawson Creek, then Burstall in Saskatchewan and Fort St John BC, Ryan played on representative teams all through minor hockey up to Junior B. The family friends in those years included the Messiers, Doug and his sons Mark and Paul. Doug played 487 games in the Western Hockey League. His son Paul played for the University of Denver and briefly in the NHL. Mark is the most complete player of his generation. Both boys developed their multidimensional games during a hockey-filled childhood in Edmonton. Mark went on to win six Stanley Cups and honoured membership of the Hockey Hall of Fame.

"Once we were ready to advance, we went to Edmonton and billeted with the Messier family and played for Doug Messier as coach," says Switzer. "My brother Erle played with Paul Messier and, at 16, I went to play for Doug Messier at St Albert Saints with Mark". The two boys attended St Francis Xavier High School while playing Tier II of the Alberta Junior Hockey League.

Despite Canada's long-held belief that major-junior hockey could not survive against the pros, Switzer joined the attempt at reviving the Edmonton Oil Kings in 1978, but the juniors were once again unable to compete and it lasted only one season. Edmonton was a small town hockey-wise, yet it produced some of the young hockey player's fondest memories. "Playing for the Oil Kings and Mark Messier with the Oilers... we were all one happy family through those early Eighties... hanging around, we were a close group. I skated with the Oilers players who didn't go on road trips, and I was fortunate I was there for the club's first and second Stanley Cups". A recent NHL fan poll voted the 1984-5 Oilers "The No 1 Greatest NHL Team". [9]

"Mark Messier and Kevin Lowe, president of the current Oilers, had a house and a small group of us would come and go. In summer, we were hardcore water skiers at Pigeon Lake outside Edmonton where the Messiers had a cabin. We skated together as a group in summer to stay in shape, worked hard and played hard. Great times all round in those early Edmonton days".

Meanwhile, brothers Erle and Darre played in Red Deer with the Sutter brothers, another of the most famous of families in the National Hockey League. Erle went on to play professionally in the Muskegon Michigan Detroit Red Wings minor league system, and Darre went to the Philadelphia Flyers via the draft and played in the American league farm team until forced to retire due to injury.

Ryan continued Major Junior A in the WHL with the Great Falls Americans (1979-80) and the Saskatoon Blades (1979-80). Paul Messier got him to Germany to play the 1980-81 season with EC Peiting in the Oberliga, the third level of ice hockey there. On his return in 1981-82, he played for the Golden Bears in the CWUAA with the University of Alberta while studying commerce and business.

Switzer arrived on Australian soil in 1987, coached by his father, along with Doug Messier, the Oil King's Norm Ferguson, the University of Alberta's Billy Moores and, of course, his mentor Clare Drake. Regarded by many at the time as the world's top ice hockey coach, Drake had preceded Switzer's arrival in Australia during a hockey building mission a few years earlier in 1984. That was soon after he coached the Canadian national team in the 1980 Olympics and the Edmonton Oilers in the NHL. Drake, who died recently, coached Alberta to six University Cup championships and seventeen Canada West conference championships in his 28 years there.

Canada built Major Junior Hockey to mirror the NHL play, a tough and rigid North-South game. Switzer felt right at home there, but the more intelligent style of University also appealed, as did the big ice, open style European game. He never represented his country, but this mix of play did shape his coaching philosophy — pull instead of push, and team over individual. Innovation as a skill and strategy, not as an objective.

Immersed in hockey culture, his family and hockey friends, Switzer's feeling for the game matured through the many relationships and coaching mentors in his father's circle of influence. "Dad was always about leadership and very proud that all three of his boys were either Captain or Alternate on respective Major Junior A teams. Erle captained the Regina Pats; Darre an alternate captain of the Medicine Hat Tigers; and me, an "A" with the Great Falls Americans, ex-Edmonton Oil Kings".

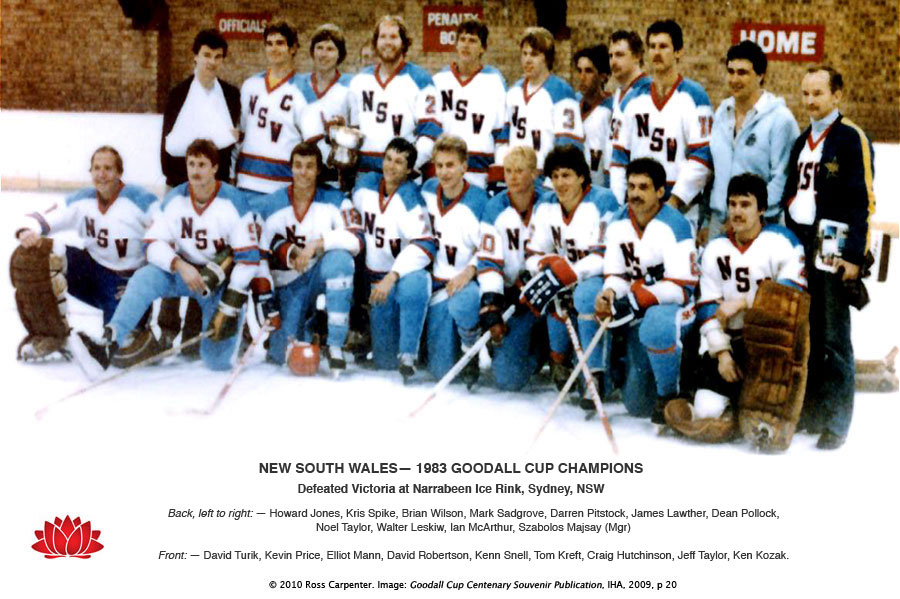

Not permitted to play the first year in Sydney, Switzer helped coach the Macquarie Bears. Still thirsting to play one last time, he joined the Bears attack in 1988 where he won the scoring title for his club, and top point scorer of the NSW Super League. The state Goodall squad coached by Garry Doré included such top overseas players as Craig Hutchinson and Jeff Taylor. That changed after South Australia won a pair of back-to-backs and the NSW state squads gave way to a wave of younger players.

"I think once again it was simply a changing of the guard. The younger players coming along had a good skill-set, but a great attitude to being coached". Switzer asked his father and Bruce Rolin if they would go behind the bench so he could play for the Goodall Cup. He won a Cup that year and the next.

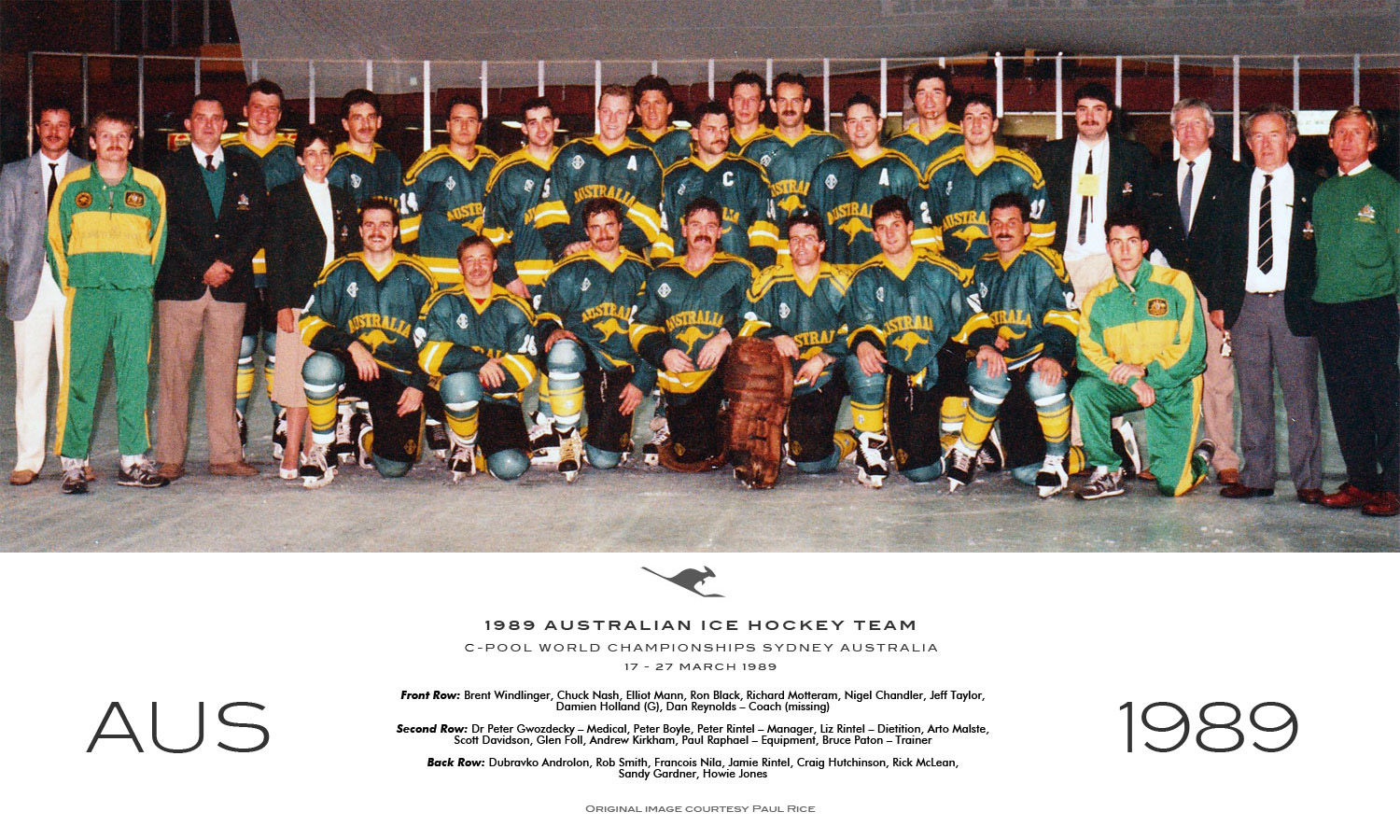

In preparation for the upcoming C-Pool Worlds in Sydney in 1989, Phil Ginsberg, the national president, asked Switzer to assist coach Dan Reynolds with the men's national team. "I stepped on the ice at training and Dan never acknowledged me, nor introduced me to the players, so I left and didn't go back". Australia lost all 7 games, finishing minus-44, a 14:58 goal differential.

"I liked the team in Sydney, but I did not like the way they played — normal, predictable hockey — they did not adjust, nor adapt to competition. Phil asked what I would have done differently and I told him. I explained the difference between coaching a team in a league, versus a short, dynamic tournament like a World Championship. It's like Rugby League and Rugby Union. Both are forms of Rugby, but totally different games".

Ginsberg offered to back Switzer for the top job in the national men's team, and he returned with an outline. "Scope, short and long-term goals, plus terms and conditions, including one hundred percent control of the entire project". That meant all personnel — admin, players and coaches, including training camps, local and overseas. "Plus a 5-year term, which was non-negotiable for me, to mould a team in the fashion I wanted". The Switzer blueprint was a hockey team, not a roster of players. The next year, he succeeded Dan Reynolds as Head Coach of the team that had been relegated to the D-Pool. In the Autumn of 1989, Switzer started work on the soul of a new team.

The new coach specifically chose players to suit the system he wanted them to play, especially those who were most open to being coached. Those who were competitive by nature or personality, rather than those for whom it was a learned trait. Those who were more naturally aligned to learning new systems, who exhibited the ability to adapt, who could buy-in fastest with the least friction.

"Obviously this meant younger, inexperienced players were no longer disadvantaged," he notes, "if they fitted these team criteria, and if the skill-set was compatible". Some like Phil Hora and Chris Blagg required special permission because they were under 18. For the first time, the pliability and adaptability of youth became weapons in a new campaign against the short preparation time available to Australia for World Championships.

"I designed a holistic approach to building a one hundred percent team-oriented structure," Switzer says on reflection, "because I wanted us immersed in team culture from the start". From on-ice flow drills with embedded objectives that the players, not the coach, had to correct and resolve; to multiple drills explained simultaneously for added complexity. From off-ice teams for gamification using riddles and brain teasers, to activities that counted for points to ingrain the teamwork principle. "Don't let what you can't do interfere with what you can," ran one official team saying. "Why?" chimes in another. "Always ask why. Never do something because you're told to, you must know why for consistent buy-in".

Only four players from the Sydney C-Pool Worlds returned to Switzer's D-Pool in Cardiff in 1990 — Holland in net, Malste and Foll in defense, and Howie Jones up forward. "When I arrived in Australia Glen Foll was one of the only NHL calibre players," recounts Switzer. "Let me explain, I am not talking about his skill level, but every NHL player has a common denominator in that they all hold 'engineering degrees', meaning solid infrastructure to their game. This means their play, positioning and read on the game is so structurally sound, so stable, so risk adverse and so consistent, it provides the platform for creativity. Damian Holland provided the same capabilities in goal. Stability in Defense and Goal were both integral to the system I was introducing, and both players played key roles".

In a tied game against Spain, the same 3 players scored and assisted 4 of 5 goals. In another against the same country, one player scored both Australia's only goals. [5] Switzer coached the Mighty Roos to the silver medal in Cardiff against Great Britain and Spain. Great Britain won promotion to Group C in 1991, while Australia and Spain took the year off because there was no D-Pool.

In 1992 at Hull in England, the IIHF introduced a secondary tier of the C-Pool, and a record 32 nations competed. Spain returned in Pool C2 and Australia in Pool C1. The average age of the 23-man squad was 24, up one year over 1990. Sydney's Warringah Bombers, the ACT-NSW Super League champions, celebrated having 7 of 23 spots on the squad — Rad Benicky, Phil Hora, Darren Johnson, Chris Blagg, Alex Ignatovich, Howie Jones and Jamie Alexander. Another 7 came from South Australia — Paul Cracknell, Peter Tonkin, Glen Foll, Andrew Brunt, Pavel Bohacik, Adrian von Einem, Paul Nesterzcuk. In fact, these two states made up most of the team, with Glenn Grandy and Paul McCorquodale from Victoria.

Hungary had just been relegated and they were not happy. "They had a superior attitude and looked down on all teams in the tournament," recalls Switzer. "They actually laughed and pounded on the glass while we had our morning pre-game skate. Our practice didn't look good because we ran through correcting and tweaking our systems, instead of normal drills. That night we beat them 8-1. They were so frustrated they imploded on the bench, players and coaching staff yelling and arguing with each other by the end of the game". Half the Great Britain team went over to shake the hands of the Australians.

Great Britain, led by Scot Tony Hand and Canadian Kevin Conway, easily won all five games and promotion to Group B. Australia won 2 games and drew another to finish with the Bronze, just a point behind North Korea with the Silver. Australia beat Hungary and Belgium, and tied South Korea, to rank 23 in the world, up 3 places from 1990. It was Australia's best result to date in Division 2, a scoring differential of -2 (24:26). Glen Foll and Paul McCorquodale were MVPs, and Damian Holland was Best Goaltender. Aside from the Division 1 (B-Pool) teams of the Sixties, it was the highest the nation would rise, right up until the present day.

Most of the squad returned with Switzer to the '93 Worlds in Slovenia and the '94 Worlds in Barcelona, completing four consecutive international campaigns. In Barcelona, three players — Charlie Cooper, Todd Johnson and Glen Foll — scored over half the team's goals and points, and two scored half the teams assists (Cooper and Delisle), but only four of the team did not score at all. No-one dominated. Everyone scatter-gunned the opposition net for an average 44 shots a game. At the other end, Damian Holland saved 88 percent from 3 games, and Tim Hulme 84 percent from 2 games. The team out-performed its top player by a country mile to take Australia to its first positive C-Pool scoring differential of all time — a plus-6 (17:11).

Yet, it was not all smooth sailing. After a poor effort in a game in the second or third campaign, Switzer found himself reminding his charges of where they had come from. He told them he thought they did better the first year when they had nothing, when they all slept together in a scout hall on camping cots, instead of fancy hotels. Next morning, when he opened his hotel room door to go downstairs, he found his team sleeping on mattresses in the corridor. He admits it brought a tear to his eye. The gesture even touched hotel staff.

Asked how he thought his campaigns went almost a quarter century ago, he said "I was very happy with the results from both achieving a team culture and the results on the ice and off. Australia was always competitive and, though outclassed at times skill-wise, we earned the respect of opponents, and they told us so.

"I knew it was a unique time with the break-up of the Soviet Union and the high calibre of competition. I thoroughly enjoyed being the underdog and I was so impressed by what my players achieved but, more importantly, how they achieved it. I had great assistant coaches and management staff. Our approach was very labour-intensive by design and we put a lot of effort in as a group, especially the overseas training camps. So, I take my hat off to all of them over the years.

"For me personally, the Worlds in Barcelona was a very special time. My father was my assistant and my brother Erle assisted with the defensemen at the training camp in Toronto, Canada. I knew one of our exhibition games was against an aggressive College team in Toronto, so I snuck my brother Erle into the Aussie defense line-up to take care of any rough stuff. To this day, I am mad that we never got a picture of my dad and I behind the bench, and my brother suited up as a player in an Aussie uniform... Representing Australia meant a great deal. To represent a country is an achievement for anyone".

IN THE 1995-96 SEASON, Switzer returned to Canada and Dan Reynolds returned to coach the men in the 1995 C-Pool. In the game against Greece, Malste and Rurak scored half the goals, two players assisted half, with 80 percent of assists from four players. Cooper scored the only two goals against Spain, and more than half against Israel. Despite the returning core of Foll, Cooper, Holland, Jones, Malste, Wand and Rurak, individual play again eclipsed team play in every game, as if Switzer's new breed had suddenly forgotten everything. Australia fell three places in Reynolds last Worlds.

Ryan returned to Canada with the goal of assisting a coach in the NHL the following year, or in the minor system. "So during the summer I used my hockey network. I ran the University of Alberta Golden Bears Training Camp and a 6-week NHL Fitness Camp as Head Instructor with Perry Pearn (NHL) and 54 contracted NHL players; two on-ice sessions per day focused on high tempo flow drills. Most Edmonton Oiler players attended". He was also assistant coach of the Medicine Hat Tigers in the WHL.

"I felt disappointed. I had the contacts, but I did not get a coaching position at the level I wanted. I was not prepared to put in the time required in the minor leagues to work my way up. I was very lucky to have a friend, Michael Barnett from EDM, who ran the Hockey division for IMG USA — International Management Group — the worlds largest Sports and Entertainment Management Group. They were agents for Wayne Gretzky and others. Michael pulled some strings and got me a job in Sydney". IMG Australia was responsible for tennis, the Australian Open, all the Golf and Rugby. Switzer's first big event was the Bledisloe Cup hosted in Melbourne for the first time. "It was a great consolation career in which I am still involved to this day".

Some attribute the success of these four Worlds squads to Switzer's coaching, and he says "I was a by-product of golden era of coaching in Canada, a time of great coaches at a high level, plus the professional experience from Europe and the Edmonton Oilers, skating and working with players that didn’t go on road trips. I found this diverse mix invaluable when it came time to formulate my own approach to coaching.

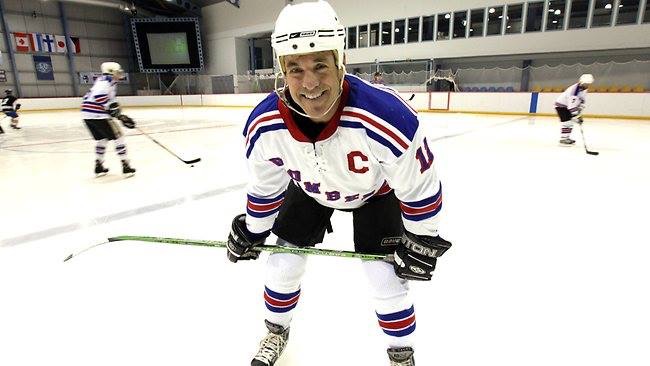

"Coaching the National team in four World Championships simply took up all my time and energy," says Switzer. "When I came back from coaching in Canada, I played for the Bombers Senior-B and was Captain for many years. I really enjoyed playing with and against many of my ex-players". He considers the time when he was coach of the national team "a great era given the calibre of competition at the time and awesome group of intelligent players". Remembered by many as their best coach, he considered the defeat of Hungary 8-1 "the best collective execution of a game plan by a group of players that I have been a part of". [1]

Switzer's solution to breaking through the glass ceiling is to not use the exceptional talent of one or two players at the expense of the team. Instead, he showed everyone how to play with those players, and how to give the kind of support that made them even better. For that to work, everyone had to learn to play a role, from the top player, to the coaching staff. And everyone had to play tactically to the plan.

On a line with a talented attacker, every team member offers up some form of support, like creating space, to boost the performance of the attacker over and above what he can do on his own. Players knew their role in helping others become even more influential against the opposition. Everyone understood their part in creating synergy, and so it was more likely to happen.

Australia's competitive reputation at these tournaments is an enduring memory. The emerging perception of the team from Down Under as difficult to play against in those years, is enshrined in the tournament programs of the time. Even outclassed, Switzer's system helped his squads play a disruptive game.

What did this performance turn-around of the national men's team in the early 1990s mean? It meant it had taken 10 to 15 years to develop enough young players locally to score more goals than they allowed in Division 2 (formerly Pool C). It meant that national teams with an average age in the early to mid twenties proved more competitive than a higher average age, sometimes as high as 30, compared to 23 or 24.

It meant players who regularly competed together from a young age, more quickly produced teamwork in the comparatively small amount of time Australia allocates to preparation. It meant teams of mostly locals bonded this way were more competitive internationally than the earlier teams of mostly more skilled and experienced players who developed overseas. It meant team respect for a coach, and coaching quality, were significant factors in team success.

In short, it meant this model produced something greater than the sum of its parts. It proved competitiveness in the Division was less about personal skill and experience, and more about team skill and experience. In years to come, it could be undone at any time by interruption to the steady flow of top junior player development and/or their exclusion from national teams and/or coaching quality. In fact, those are the reasons it took 30 years of international competition, from 1960 to 1990, to adapt the top-level of local competition to Division 2 standard.

Switzer focused on players using a pull, not push, method. His strong belief in "the whole is greater then the sum of the parts" idea, carried over to his business career. He found innovation very effective in 5-man units, and the success of his player's implementation of that model reaped rewards in high-level competition. "The complete buy-in, the consistent execution, the resulting payback was awesome. I was so proud and happy for them to have their hard work payoff. To this day, their positive feedback on the overall experience is humbling. It was a unique timeframe for hockey worldwide, and one that I believe the players did not get credit for, even to this day".

Switzer enjoyed boxing during his hockey career and considered it a great tool and advantage. He still enjoys gym and staying in shape. His wife Gale is also very athletic and active, and their ten year-old daughter Jordyn pursues soccer and dance. In 2014, he worked with Moore Sports, the group that brought in the Major League Baseball games to Sydney, winning the global sports stadium event of the year. All a far cry from the national team he led to 23rd in the World in 1992.

Acknowledged as the most successful Coach of Australia in his time, in retrospect, Switzer's results belong to one of the top few Australian senior team coaches of all time. The contribution is comparable to Bud McEachern at the Olympics in 1960 and '64. Botterill and Fuyarchuk's pioneering National Youth Teams. Even then, there is mounting evidence Switzer's contribution to coaching here was more valuable going forward.

After the curtain went down on Australian ice hockey in the Eighties, another went up on a new breed of team at the dawn of the new decade. The young athletes of Ryan Switzer's assault on the world stage, broke with old school ties and ad hocery, to blaze a path into the unchartered territory of the nation's international game. They delivered the most competitive and sustained ice hockey results Australia had achieved up until then, by raising the sum of their parts to something greater. Yet, for some inexplicable reason, their labour of love and the secret to its chemistry — their legacy — are either misunderstood or ignored.

Historical afterword

In 2018, an Olympic year, Australia finished 36th of 50 in the IIHF world rankings, determined by a complex formula taking account of performance in the previous four worlds. But the nation dropped as low as 38 after the Olympic results. Begun in 2003, the rankings show the long-term quality of a country's national team program, and 15 years on, Australia is where it began that year, peaking at 31 in 2009. Bronze in 2006 under Don Champagne, Silver in 2007, then Gold and promotion in 2008 under Steve McKenna. In Division 1 in 2009, Australia lost all 6 games and dropped back to Division 2.

Many of the nation's world-class representative teams in other sports are all-Australian, even though the percentage of overseas-born Australians has almost tripled since the last world war. Today, an Australian National Team representative of that demographic (28%) would have three Australian-born players for every one overseas-born player. In a four-line ice hockey team, 6 of 22 players born overseas is representative of the population. But there have been many more than that, and not from the nation's naturally occurring overseas-born demographic. They are new arrivals who receive incentives to play here.

At the 1987 IIHF Worlds in Perth, 14 of 20 players were born overseas. Back then, a 20-strong team with just 6 born locally was not Australian. It was proudly un-Australian. The Ginsberg administration made inroads in correcting the imbalance, and perhaps at times they even over-corrected. Some natural "New Australians" were stood down from national junior teams in favour of those born locally.

By 1990, when the ratio was about 23 percent, there were around 9 overseas-born players in the national team, still almost double the expected 5. But the change was mainly achieved by deliberately reducing the quota of imports permitted in the feeder leagues to the National Team. To give locals a fair go. That's what the IIHF is on about.

The import restrictions have not changed in the 30 years since then, still 4 per team. Yet, the number of Australian-born and raised players in the national league is again rapidly reducing. Some no longer consider it Australian ice hockey because clubs short-cut local player development by recruiting overseas players and naturalizing them. Sometimes that occurs within a few short years, the limit of the IIHF player eligibility rules.

A player born and bred overseas to Australian parents receives the same privileges as a player born and bred here. That's a loophole. Unlike New Zealand ice hockey, there is no quota on naturalized imported overseas players. Nor are there incentives for national league clubs to develop local homegrown players. There are, however, plenty of ready-made overseas players, any shape and size, any skill and experience level.

Why doesn't Australian ice hockey have a quota on naturalized overseas players like New Zealand? At the time of writing, it either cannot control that in its affiliated men's national league, or it chooses not to. And, going forward, that will depend on who pulls the levers. Either way, priority is given to developing a professional entertainment league, over the performance of national teams at IIHF championships, even though the national league was explicitly created for just that purpose. Its original goal is to eventually return Australian ice hockey to the Olympics by giving local players higher level experience here and overseas.

This also costs the amateur game in other ways. We play opponents coming off their season at their peak, when our season is yet to start and we are at our weakest. Because, unlike all our other national league ice hockey teams, the men's fixture is timed to allow for 30 or 40 league imports to play here during their off-season.

There is little or no net benefit to local players by raising national league and national team quality like this. It is a logical fallacy, because the disadvantages cancel out the advantages. Naturalized imports displace some locals in the national league and national team, and all locals represent Australia at a monumental scheduling disadvantage. Similarly, the national league does not allow the three 20-minute periods of play that local national team players encounter in international competition.

This hybrid national amateur and "entertainment league" began 38 years ago in Pat Burley's short-lived NIHL, and staggered on through the quasi-national NSW-ACT Super League to the AIHL. Of course, organisers do know the beneficiaries are not the locally born and developed players, but the imports, the paid officials, media services, and others who are remunerated one way or another from the player's sponsors, their payments to play, and their gate-takings. The league cannot otherwise pay its way.

Any net benefit to the amateur game derived from an entertainment league like this should appear in the performance of the amateur national team. It did improve in the rankings, then plateaued for half of the league's 18 years, only to decline again to the all time low. The decline followed a sharp rise in the number of naturalized imports, and the resultant displacement of locals over the past 5 years. Australia is again ranked 36 in the world in 2018, which is where it was when the national league began.

The national team and national league of most countries are meant for athletes who are representative of their populations, not the populations of other nations, as has sometimes been the case with ice hockey here. Who are more deserving than the young players who have financed the sport here for 10 or 20 years? These four national team squads coached by Ryan Switzer are a masterclass in the reasons why.

[1] Legends of Australian Ice Facebook, 2018.

[2] The Two Mental Shifts Highly Successful People Make, Stephen Covey.

[3] Synergy in Sport Teams: creating high performance teams, Bo Hansen, Mooloolaba, Queensland, Australia. Hansen is a 4 time Olympian and coaching consultant.

[4] Worlds stats, Birger Nordmark.

[5] Team Australia, 1990 IIHF D-Pool Worlds, Cardiff, Wales. Damian Holland, Ron Klajnblat, Andrew Watts, Jim Kinlough, Arto Malste, Howard Jones, Glen Foll (C), Jarrod Scott, Chris Blagg, Glenn Grandy, Phil Hora, Darren Johnson, Todd Johnson, Adam McGuiness, Peter Tonkin, Robert Stark, Phillip Ross. Ryan Switzer (Head Coach), Szabolcs Majsay (GM).

[5] Team Australia, 1992 IIHF C-Pool Worlds, Hull, England. Damian Holland, Tim Hulme, Paul Cracknell, Radomir Benicky, Pavel Bohacik, Alex Ignatovich, Howard Jones, Glen Foll (C), Adrian Von Einem, Chris Blagg, Glenn Grandy, Phil Hora, Carl Di Piazza, Todd Johnson, Adam McGuinness, Peter Tonkin, Andrew Brunt, James Alexander, Chris Rurak, Murray Wand, Paul McCorquadale, Darren Johnson, Paul Nesterczuk. Ryan Switzer (Head Coach), Szabolcs Majsay (GM).

[6] Team Australia, 1993 IIHF C-Pool Worlds, Ljubljana, Slovenia. Jason Elliott, Tim Hulme, Paul Cracknell, Robert Avey, Radomir Benicky, Pavel Bohacik, Glen Foll (C), Alex Ignatovich, Howard Jones, Jarrod Scott, Trevor Allen, David Batho, Chris Blagg, Charles Cooper, Carl Dipiazza, Phil Hora, Todd Johnson, Chris Logue, Paul McCorquadale, Troy Morgan, Paul Nesterczuk, Paul Stables, Murray Wand. Ryan Switzer (Head Coach), Szabolcs Majsay (GM).

[7] Team Australia, 1994 IIHF C-Pool Worlds, Barcelona, Spain. Damian Holland, Tim Hulme, Radomir Benicky, Pavel Bohacik, Glen Foll (C), Jim Kinlough, Ross Moffat, David Batho, Chris Blagg, Andrew Brunt, Charles Cooper, Joseph Delisle, Phil Hora, Todd Johnson, Howard Jones, Troy Morgan, Chris Rurak, Murray Wand. Ryan Switzer (Head Coach), Szabolcs Majsay (GM).

[8] Biographical notes and conversation with Ryan Switzer. Ross Carpenter, June 2018.

[9] The No 1 Greatest NHL Teams, NHL Centennial Celebration fan poll, National Hockey League, 2017.