With St George, NSW Premiers, Prince Alfred Park rink, Sydney, 1963. Courtesy Elgin Luke. From left: Ray Parsons, Elgin Luke, Roddy Bruce, Phil Hall, Charlie Grandy, Rob Dewhurst, Bruce Thomas, Vic Mansted.

With AUS National Team

Elgin Luke, Charlie Grandy, and Phil Hall, newly arrived Canadian expats, were hard at it. But it did start better for some than others. A puck from Charlie Grandy's stick broke Elgin's nose in the warm-ups! Olympic Ice Hockey Playoffs Warm-up, Tokyo, 1963. Courtesy Jacqui and Elgin Luke.

VIHDC

Elgin Luke and the Ministry of Youth

![]() Import players add a lot of flavour to the game here. But to be honest about the whole matter, I don't believe they're the answer to us moving ahead. Let's face it, it isn't really an Australian League or system when you have the majority of your national and state squads made up of overseas players.

Import players add a lot of flavour to the game here. But to be honest about the whole matter, I don't believe they're the answer to us moving ahead. Let's face it, it isn't really an Australian League or system when you have the majority of your national and state squads made up of overseas players.

— Expat Canadian Elgin Luke, Australia's first National Coaching Director for ice hockey, Blades newsletter, 1981. [2]

IN 1961, ELGIN LUKE, a recent representative of Eastern Canada in the finals of the Minto Cup, quit his job in Whitby and headed to Australia to bum around with his hockey and lacrosse mates, Phil Hall from Toronto and Charlie Grandy from Brooklin. They ended up on Sydney beaches, living the surf lifesaver's dream from rented flats at Tamarama and Coogee in summer, and playing ice hockey in winter. Luke and Grandy soon decamped to Melbourne, on the south of the continent, where they found another bunch of ice hockey tragics plotting their return to the Olympic stage. Luke didn't know much about the other expats like Russ Carson and Bud McEachern. But there was a buzz in Victoria. Something was happening. And, soon enough, he found himself watching the sun rise over St Kilda beach with some of the most ambitious sportsmen in town.

Nineteen sixty-eight was the last time Olympic ice hockey counted as the World Championships. The best players on the European teams were de facto professionals. Canada followed suit at the 1970 World Championships with approval for nine non-NHL pros, but withdrew from international ice hockey competition when the decision reversed. By 1975, the year the IIHF re-aligned the tournament for NHL players, organizers in Australia had already shifted their attention from the costly Olympic ice hockey forays of the early Sixties, to the World Championships.

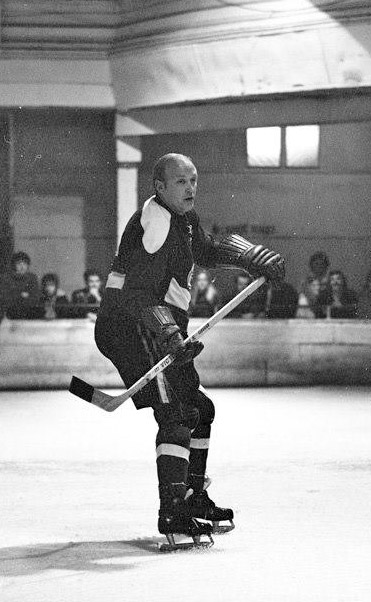

Elgin Luke, Monarchs, St Moritz Ice Palais, Melbourne, early 1970s. Courtesy Steve Duncan.

Elgin Luke, Monarchs, St Moritz Ice Palais, Melbourne, early 1970s. Courtesy Steve Duncan.

A system of self-interested seniors, and a poverty of junior development, characterized the Australian game back then, but less so in Victoria than interstate. The idea that this difference was due to the greater number of rinks in that state was so pervasive, even Victorians believed it. But it was still not true. Victoria only had two or three ice rinks and, up north, New South Wales had two or three times that.

If Victoria had an edge, it was more likely to be a hangover from the wartime junior hockey schools and house league set up in Melbourne by the Canadian expat, Russ Carson, and local boy, Chook Tuckerman. The new crop of youngsters, which included most of the nation's first ice hockey Olympians, were the foundation on which Victoria built an enduring post-war preeminence.

Victoria dominated the Goodall Cup after the war. They also won nine of ten Brown Trophies, the reserve competition, up until 1973. But one generation of developed players may not last twenty years of senior competition, and the use-by dates of the wartime batch began to expire in the mid-Sixties. Without a replenishment system, that was a problem. The age-delimited hockey and speed skating league pioneered by John Goodall for teens had lapsed, and there was still none in the hockey landscape thirty years later.

Bruce Charman coordinated a junior program in Melbourne, a low-key affair, even compared to the war years when senior competition had also all but lapsed. Sydney had the Homebush Juniors which affiliated as the NSW Junior Ice Hockey Association (under-16) in 1974. While it aimed to administer a junior program and promote, encourage and publicise its growth and quality, it was not a player development system.

In Victoria, the Clubs and associations of Stan Gray's era were "scared of letting go of their domain". [1] They focused instead on shoring up their clubs by recruiting internationals. An avid Richmond Football Club supporter, who picked up ice hockey along the way, Gray was national president from 1966, and he turned his personal sporting agenda to great advantage with the Raiders and the Black Hawks, the dominant ice hockey clubs of the time.

By the early Seventies, Luke found himself investing less time coaching the National Team proper, than preparing each player for Australia's return to the IIHF World Championships in 1974. After a middling performance at the senior Worlds at Grenoble, the penny dropped. Why not get more involved with developing young players? That same year, the IIHF rolled out an unofficial invitational tournament for juniors which would become the IIHF World Under-20 Championship.

The building of Luke's vision started with notices on walls at rinks inviting interested kids to learn to play ice hockey. The training clinics that popped up at each suburban venue gradually built up to incorporate power skating tuition by figure skaters, goalie clinics, and sports medicine.

But the project had its detractors. Gray held it back, recalls Luke, "because he thought he was going to lose some of his Black Hawks". [1] Luke parted resistance as the clinics blossomed, pioneering a youth development pathway. First an Intermediate level, then a Senior one, then expansion to embrace state player selection for the Tange Trophy, the Under-18 national tournament begun years earlier in 1969.

Although international ice hockey competition for young Australians was still some years off, the IIHF granted full Worlds status to the World Juniors championship in 1977. In 1979, the year seniors returned to the Worlds with Coach Dan Reynolds and Stan Gray, Luke sought and received permission to use the five-level player development program of the Canadian ice hockey association. He was a few steps ahead of the IIHF, who adopted a similar system in the early Eighties. The government department responsible for the National Coaching Accreditation Scheme in Australia said no to five levels, but agreed to three. It was a big improvement on none.

Australian ice hockey organisers faced a brave new task moving into the Eighties—keeping up with the Jones's. The birth of the Canada Cup World Cup of Hockey tournament brought together the best hockey players from the sport's six leading nations. To keep pace with Canada, the USA and the Soviet Union, countries like Sweden, Finland, Czechoslovakia, and later West Germany, Romania, Japan, Holland and Norway, had to increase the standard of their hockey development program to the point where youngsters trained from childhood to play at world-class levels.

Luke attended coaching symposiums in Sweden in 1979 to gather information on the international model. He moulded the Australian system into a North American-International hybrid. He recruited Syd Neate, Max McKowen and his wife Joan for sports medicine, and later Paul Watson to help with player camps. The McKowens became a big part of the enterprise, and Watson became one of its great ambassadors. Junior development snowballed in Victoria. Branded white on the dark navy of the state's ice hockey finery, this veritable ministry of youth development was a shot to the veins of Australian ice hockey.

But, before then, it was known as the VIHDC. The Victorian Ice Hockey Development Council.

Maybe I'm just too demanding, shudders a Walkman on the change room shelf, peeling back the flaky, two-tone wall enamel.

Maybe I'm just like my father / too bold.

It may well be the soundtrack of his life, but the young hockey player dripping sweat underneath doesn't seem to care. "We're Gen X, the MTV Generation," he says in a voice raised only slightly above the synthpop. "We're told over and over, the ones who actually did things were the generations before us".

Maybe you're just like my mother / she's never satisfied.

"The Baby Boomers got herded into the slaughterhouse called Vietnam, toppled a President, stared down the chaos of the Sixties, and fought to change the world. Their parents fought Hitler and freed Europe. Their parents struggled through the Depression, and their parents fought in the trenches of World War One. What have we done? What have we suffered? What have we sacrificed? Not a lot. Our miseries are not born of chaos, war and destruction. They're tiny personal tragedies, in their way insignificant".

This is what it sounds like / when doves cry.

"Well, you know what?" said the boy. "Bull!

"In a world where communication is everything, maybe we did forget to talk to each other. Maybe we forgot to be people. But life is not about being a Real Man, or a space monkey. Not about a unique snowflake. The cautionary tale for our gen is we are not the club we belong to. We are not our scars. We are neither worthless nor undeserving. We are what we make of ourselves, what we make of the world".

Much of the youth Luke trained grew up in a time of increasing divorce rates, a time less focussed on children than adults. Their Boomer parents were "the most divorced generation in history" [3] and the limited or severed relationship was often the father. Many lacked supervision between the end of the school day, and the return of a parent in the evening. Gen-Xers were more peer-oriented than earlier generations. About one in six grew up in poverty.

At that time, ice hockey in Australia increasingly drew players from a kind of parallel universe situated somewhere in North America. More on-ice incidents resulted in law suits there in those years, than at any other time in history. Brain damage that resulted in lost seasons. Life-long injuries for victims. Years of bans and convictions for offenders.

If hockey did not condone illegal violence for aggression's sake back then, it offered it up like a fight club without the consent. A route to "enlightenment". A way to turn in and fulfil yourself, and not let society do it. Although a few top players such as Wayne Gretzky campaigned against this, whole decades had gone by when in 2012 the Governor General of Canada, David Johnston, said that violence such as head shots, high-sticking and fighting should not be part of the game. [4]

HE WAS BORN MAY 20TH 1939 in MOOSEJAW Saskatchewan in Canada, the son of wheat farmers Joe and Lillian. Luke's father worked in the silos of Saskatchewan, then Whitby where Elgin grew up from the age of 4 in a bright childhood against the faint backdrop of industrial grey. Although his father skated, he never played hockey, contenting himself with lawn bowls, baseball and curling. Joe ran a furniture and TV repair business in later years and did admin for Whitby Minor and the Hillcrest Juniors until a heart attack at 52 proved fatal. [1] Luke's mother lived until 86.

The industrial town on the north shore of Lake Ontario was home to 14,500 people in 1960. Now it is a commuter suburb of the Greater Toronto Area. GMH in Oshawa is still the major regional employer, supported by a steel mill and many other manufacturers. The town put on hockey competitions for Peewees, Bantams, Midgets, Intermediates, and an Industrial League. Luke developed his game in them while attending Toronto High. He says his younger brother Gordon could have done well in the NHL, but he preferred to play for fun.

Like hockey, lacrosse has long been prominent. The Whitby Dunlops captured the World Championship in Oslo in 1958, featuring long-time president of the Boston Bruins, Harry Sinden, and former Mayor of Whitby, Bob Attersley. The Brooklin Redman Senior A club is one of the most successful in Canadian sporting history. The Jnr A Whitby Warriors won the Minto Cup four times since 1984.

Luke played lacrosse in the Whitby Red Wings of the Ontario Junior A Lacrosse League with Hall and Grandy. He made semi-pro for the Ohio Troy Bruins in the USA for one season, but felt he was not good enough. In 1960, all three won the Iroquois Trophy and represented Eastern Canada in the finals of the Minto Cup, awarded annually to the national junior champion. They lost to the Westminster Salmonbellies of Vancouver.

On a visit to Sydney Australia in the early Sixties, Hall suggested Luke and Grandy join him. They arrived in 1961, when Luke was a young twenty-something, and lived beach-side in flats at Tamarama and Coogee. Taken by the surf and sun, Luke earned a Bronze Medallion in lifesaving at Tamarama, and played baseball with Manly and Warringah. In winter, the trio played ice hockey for the 1963 NSW Premiers, St George. They went on to represent NSW that same year, winning their first Goodall Cup.

Someone from the Black Hawks club in Melbourne invited Grandy to join the team, and he moved south in 1964. Luke went to the Gold Coast where he met Carol, then back to Canada where they married. They returned to Melbourne, Carol's hometown, after eighteen months. The National Team took in Luke, Hall and Grandy, and they represented Australia against Japan at the Winter Olympic Playoffs in Tokyo. "Well organized, and facing-up to what we had," recalls Luke. He continued on in defense for the Black Hawks for six years, coached the team in his last season, and played lacrosse with Grandy for the 1966 Caulfield A Premiers.

Luke won three Victorian Premierships, the Kleiner Trophy, as player-coach of the Monarchs. He won two more Goodall Cups as a player in 1967 and '68, and then coached Victorian State teams, winning the Goodall Cup a further five times in succession, 1972 to '76. Eight all up.

He managed five straight with a core of fifteen players who played three or more of the five: Goalies Barry Harkin and Anders Wiking. Grove Bennett, Jim Christie, Gary Croft, Sandy Gardner, Glen Gilbert, Charlie Grandy, Jim Hannah, Malcolm Heath, Ian Holmes, John Horsnell, Fraser McDonald, Russell Poste, Rob Stevenson.

Most were expat Canadians or Europeans, with twenty-eight others interspersed for one or two Cups, four or five new players each series. Victoria had done this once before in the Fifties, but never with the one coach.

Appointed Coach of Australia for the Worlds in Grenoble France in 1974, Luke won the top job again when Australia hosted the West Germany Olympia 80 tour at Ringwood Iceland in Melbourne in 1977.

THE DEVELOPMENT COUNCIL'S early program targeted male and female players and coaches at Melbourne's Oakleigh, St Moritz and Ringwood rinks. It taught life skills, teamwork, conduct, pride of place, equal opportunity, perspective on sport and, moving forward, life goals and enjoyment. The sport grew due to these developed players, then accelerated under the added influence of the Swedish program.

Some of the Council's activities ran from Luke's Dowdals sports store on the corner of Chapel and High in Windsor, one shop back from the hotel. The same family had owned it for fifty years when Luke took it over and introduced Koho and Jofa ice hockey equipment. A network of State Coaching Directors sprang up, and the National Coaching Council met annually wherever the camps were held. They approached equipment suppliers for pricing, and conscripted referees and medics to help.

Luke's Council monitored the success of its development program through player evaluations, but the increase in numbers of both players and teams was plain to see. Sports medics from around the nation attended the Council's annual All-Star Week of representative teams, and a Minor Hockey Week ran for the Peewee age-band, right through to Midgets. Recounting the Council's progress in an interview was emotional for Luke, and he turned away with a sob.

Syd Neate joined Max McKowen as another right-hand man for first aid, so that there was always someone qualified on the bench. Bob James and his wife Jean volunteered time as secretaries, and helped run the VIHDC program at Oakleigh and elsewhere. Grove Bennett Jnr helped until he returned to Canada for fifteen years where he ran Boomer's Tennis Camps.

Grant Goddard taught power skating. Ian Holmes, a great player with the Monarchs and the National Team, also helped although he was more advanced than they could handle. Holmes' son, Simon, ran goaltending clinics, and became a VIHDC Instructor and Player Development Director.

IIHF funding was slow to arrive, and by 1980 the Development Council was financially still a "bit of a struggle". Even its manuals were still printed privately by the Council's Bob Blackburn. Led by Charlie Grandy at the time, State hockey experimented with a "rapid influx of players". [6] The Council ran the interstate teams for the first time that year, and again succeeded in winning the Under-18 competition, the Tange Trophy. [6] Luke had been Victoria's Coaching Director for some years by then, the primary initiator and planner of the Council's programs for developing not only players and coaches, but also referees, off-ice officials and trainers.

"We are the biggest and most progressive state in Ice Hockey in Australia," wrote Grandy "and as such we must keep open minds, not lock ourselves in concepts, as was done in North America for twenty-five years... Sometimes, people want to keep their team or club strong at the expense of the player, [but] this must not be allowed to happen. We must have more grades of hockey so that the player is allowed to expand his ability in gradual increments. Anyone who witnessed nine year-olds trying to play against fifteen year-olds will know what I mean". [6]

Victoria's under-16s won eight straight Tange Trophies from 1975. In 1981, a new national administration led by Ginsberg and Grandy adopted the Council's development program and appointed Luke to a new position of national coaching director. Syd Neate handled the sports medicine and former Brandon University Bobcat, Mike Johnston, launched his coaching career assisting Luke. It was a career that led to the NHL.

Over the next ten years, Luke continued to coach. He and Carol had three sons, Shane Patrick, Elgin John, and Craig Alexander. After a divorce in 1983, he remarried to English-born Jacqui who has two children from a previous marriage named Nicky and Steven. Although chosen for the Australian Junior Ice Hockey Team, Shane preferred to play in Canada. Elgin Jr had good hockey IQ, played inline, and captained a Worlds inline team for Australia. Over the years, Luke's mother visited Australia three times.

In 1983, Australia launched its first National Junior Team (under-20). The first National Youth Team (under-18) followed at the Asian Oceania Championships in 1984. Victoria won the first three Defris Trophies when the national under-15 competition began in 1985, along with three more Tange (under-18) in the same years. The national senior landscape was also changing. While eight or more overseas-born players filled out the 1974 National Team, and at least six in 1979, a limit of five came in when Australia returned to the Senior Worlds in 1986, this time for good.

Appointed Head Coach of Australia's National Youth Team in the Asian Oceania tournament in Japan in 1992, Luke relocated to Queensland in 1996, where he coached state teams in the National Championships. Robyn and Sharon Burley contributed power skating tuition at hockey schools in Queensland and got Luke involved in the Association. Introduced to inline hockey by ice hockey player Barry Bourke, Luke became national coaching director for inline, and went on to coach three World Championship teams in Austria, Canada, and Italy. [1]

In 2000, national president Don Rurak reprised Luke's role as National Coaching director for ice hockey. He attended more coaching symposiums in Vierumaki, Finland on three occasions in 2004, '06 and '07, the last with Simon Holmes. Arte Malste, a product of the Finn system, pursued a long career here with the Adelaide Flyers in the NIHL during the Eighties, and then the National Team. But with the first generation of Development Council players expended, it was too late. The 90 year-old Goodall Cup competition had already collapsed, and so too the NSW Superleague. In their place was the Australian Ice Hockey League. The Development Council that Luke had championed supplied most of the new League's players, coaches and officials.

"Switched-on and in the front seat with the IIHF people," says Luke of Rurak, "he was influential in securing a lot of help from the international ice hockey field, and from other programs". In 2008, without even a whisper from the association, Luke was "pushed out the door for being there too long". [1] A Life member of the Victorian and Queensland associations, the national body bestowed on him the same honour on October 18th 2008 in Sydney. "It could have been done better," he says ruefully.

For Elgin Luke, hockey is "more than having a skate. Young players need tuition, life skills and hockey skills". He said strong personalities helped the program, and players such as Paul Watson, Simon Holmes, his own sons, and many others were the reward. Counted among his successes are the first roles for sports medicine and the junior team manager, and an improved standard of refereeing.

Active in Australian ice hockey for nearly half a century, Elgin Luke turned 80 in May 2019. Among the highlights of his career are representing Australia at the 1964 Olympic Playoffs and the 1974 World Championships, coaching Victoria to five Goodall Cups, and winning the Kleiner Trophy at four different clubs.

If a genie gave Elgin Luke three wishes today, he would still be playing, still be useful without growing too old. "To continue the success of the Development Council," he says "and all we did to keep up high levels of competition". He would win a Kleiner Trophy for the Blackhawks and Life Membership at the Club. And he would win the national association's Hudson Trophy.

Longings for acknowledgment of a career well spent.

Afterword

Today, the Hockey Canada Skill Development Model [5] is peppered with the wisdom of a generation or two of player development. "You need to practice to become a better player," it says, quoting Paul Kariya. "You see some kids playing 60 to 70 games, that's almost too much for a 15 or 16 year-old. When you are 6 to 10 or 6 to 12, you've got to be practicing all of the time".

The Initiation Program recommends player development be built on practicing technical skills 85% and individual tactics 15%. Skills practice reduces progressively over five levels—Novice, Atom, Peewee, Bantam and Midget—allowing for the introduction of team tactics, team play, and strategy. They say one efficient practice will give a player more skill development than eleven games collectively. Each player should have a puck on their stick for 8 - 12 minutes, and each should have a minimum of 30 shots on goal.

More is not better; execution of what you do is development. No more than five minutes should be spent in front of a teaching board each practice.

Citations

1. Structured video interviews with Elgin Luke, Ross Carpenter, June 2019.

2. Blades newsletter, c1981.

3. The Generation Map, McCrindle Research Centre. In the ABC of XYZ, understanding the global generations, Mark McCrindle, Sydney, UNSW Press, 2014. abcofxyz.com. Generation X is the demographic cohort following the Baby Boomers and preceding the Millennials, born 1965 to 1980, give or take a few years each way. The second generation of ice hockey players after the second world war war were mostly Gen-Xers, and the first Australian-born players to benefit from a junior development system at home.

4. Fighting has no place in hockey, GG says, CBC, Jan 26 2012.

5. Skill Development Model, Minor Hockey Development Guide, Canada Hockey, 2013

6. VIHA President's Message, Charlie Grandy, 1980.

With Rangers v Saints at St Moritz, 1980-1. From left: Syd Neate, Bob Blackburn, Elgin Luke.