National president, Syd Tange, congratulating the Victorian Men's Ice Hockey Team. VIHA Finals, St Moritz Ice Palais, Melbourne, August 1972. From left: Russell Poste, Howie Freill (G), Anders Wiking (G), Syd Tange, Lars Erik Jonsson. Victoria defeated New South Wales in 3 tests: 8-1, 6-0, 2-2. Birger Nordmark Archive.

1962 Worlds

Standing, from left: Syd Tange, Rob Barry (Referee USA), Russ Carson (Mgr + Coach Australia), Bob Crosby (Sports Store Madison Square Gardens USA), Bill Riley (Referee USA). Kneeling: Not known, Vic Linquist (Referee). 1962 World Ice Hockey Championships, Colorado, USA. Birger Nordmark Archive.

A hotel someplace

Part 2: Juniors in search of excellence

While it cannot be denied that ice hockey is the fastest game in the world, it must be conceded that Australians have not reached the speeds attained by the crack Canadian combinations. Still, the Australians are not far behind them, and some of our best men would hold their own in teams in the Dominion. Where practice can be had at almost any time of the year, it is natural that the game should have grown apace and that crowds at between 20,000 to 40,000 people should gather to witness the matches...Though several suggestions have been made to bring some of the Canadians here, nothing has been done owing to the heavy expense that would be incurred. It would not be wise to bring only one team. Two teams to play exhibition games would cost so much that it would be almost impossible to finance the tour. It may become possible, but at present the possibility seems very remote. We can only improve our own game here and hope that some day we may match a Canadian combination.

While it cannot be denied that ice hockey is the fastest game in the world, it must be conceded that Australians have not reached the speeds attained by the crack Canadian combinations. Still, the Australians are not far behind them, and some of our best men would hold their own in teams in the Dominion. Where practice can be had at almost any time of the year, it is natural that the game should have grown apace and that crowds at between 20,000 to 40,000 people should gather to witness the matches...Though several suggestions have been made to bring some of the Canadians here, nothing has been done owing to the heavy expense that would be incurred. It would not be wise to bring only one team. Two teams to play exhibition games would cost so much that it would be almost impossible to finance the tour. It may become possible, but at present the possibility seems very remote. We can only improve our own game here and hope that some day we may match a Canadian combination.

— Ted Molony, Captain of Victoria, 1928. [2]

Birger Nordmark Archive.

Birger Nordmark Archive.

A WINTRY MELBOURNE DOCKLANDS is less cold than bitter, the wind-chill robbing enough body temperature to make even the O'Brien Icehouse seem a warm haven. There is snow in the mountains when I leave, heading south down the length of Pearl River Road for a glimpse across the oldest and largest surviving single dock in the world. Once a busy berth for twenty-one ships, the new blocks of glass towers have changed that, even though their facades tell no better story. I have come to see the timber hull and masts across the harbour, Australia's oldest tall ship under restoration.

Her name is Alma Doepel, a father's tribute to his youngest daughter, and she sailed mainly around the coast of Australia carrying goods such as timber, wheat and jam. The Mate in those first years arrived in 1874 from Odense, Denmark, and qualified as a master and pilot of coastal trade ships. He drove cranes later on, at the Goodlet & Smith timber yard in Pyrmont, Sydney. His son was also one of the first Alma Doepel crew members at 13 or 14.

Even in the biting cold, head bowed against the stinging sleet, I feel that certain symmetry, that certain texture, bringing life to creaking timber. The names of these two early mariners were Charles and Carl Tange, grandfather and father of ice hockey administrator, Syd Tange. Their ship still docks down the road from the National Ice Sports Centre, just as it has done since Australia's first competition ice rink was built further up river at the turn of last century.

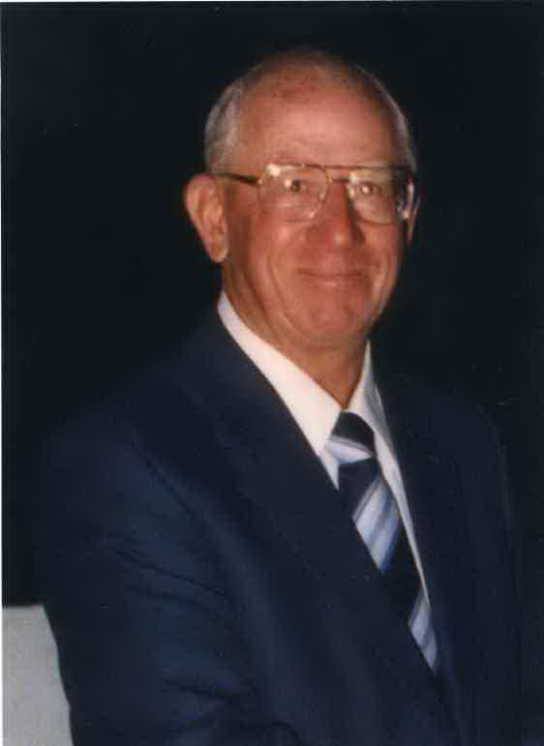

Syd took up ice hockey in Sydney with the St George club in 1937. He played for ten years, then made his mark in sports administration, first as secretary-treasurer of his Club, then president of the Glebe and East Monarch clubs, assistant treasurer of the state association, and eventually secretary-treasurer. Tange won a Goodall Cup as team manager representing New South Wales in Melbourne in 1952, and he was Assistant Manager of the Australian team competing in the 1962 A-Pool World Championships in Colorado, USA.

State president from 1964 to '66, he received the Hudson Trophy for long service to the sport in 1967, 30 years on from when he began. A mason, and Master of Lodge King of Tye, he served as national president from 1970 to '73 while working variously as a radio assembler and stores supervisor. The top jobs in ice hockey were not his for long, but he was a much-loved presence over a lifetime in the sport.

Co-organisor with Alwyn Stuart of Australia's first interstate junior hockey match in 1951, Syd Tange became a shining beacon for a disaffected junior movement in a perfect storm. A member of the Francis Drake Lawn Bowls Club, he kept himself in good shape, and presented the Tange trophy wherever it traveled, right up until his death on October 24th 2005.

Soon after the first Tange National, a former Air Force nurse, and secretary of its Women's Auxillary, managed the state's under-16 teams to their second victory. Her son played the sport at a time when the attitude of most local clubs bred a growing discontent with the neglect of their junior members. The exclusive interests of club officials in senior hockey cost the under-16s, especially in coaching, until it was no longer tolerated by paying parents.

Marcia Sheard was fair but firm and worked tirelessly. A veteran nurse of returned POWs from the infamous Changi camp in Singapore, she became foundation secretary of the affiliated NSW Junior Ice Hockey Association (under-16) when the state's affiliated Pee Wee League, which began as the Homebush Juniors, shut down in 1974. Her Association promoted, encouraged and publicised the growth and quality of junior ice hockey, and administered the junior program under association rules.

"Marcia was a capable secretary," wrote Tange, "who worked very hard for United International. She did have a tendency to sidestep official channels and guidelines which on occasion incurred the wrath of the national association". But even a cursory reading of Tange's own history reveals a state association so preoccupied with amateur bureaucracy and infighting, it was dysfunctional. At points in time, it just collapsed, abrogating its responsibilities to its members.

With a single association vote, Sheard successfully organised the new junior movement, along with the state Tange Trophy teams. It lasted until the complete reorganisation of the state association in 1979.

At the same time in Victoria, Elgin Luke also decided to get more involved with developing younger players, mainly due to the middling performance of the seniors at the 1974 Grenoble Worlds. Training clinics popped up at each suburban venue, then expanded to include power skating tuition by figure skaters, goalie clinics, and sports medicine. Luke parted resistance as the clinics blossomed, pioneering a youth development pathway, the Victorian Ice Hockey Development Council. First an Intermediate level, then a Senior one, then selection of players for the junior Tange Trophy.

At the international level, the IIHF held the first official tournament for juniors (U20) in 1977, although dominated by the world hockey powers. The Federation compensated with three lower divisions of separate tournaments based on a promotion and relegation model common in European leagues.

In 1979, Canada's association gave Luke permission to use its five-level player development program. Victoria's under-16s won eight straight Tange championships from 1975, and in 1981 the new national administration led by Ginsberg and Charlie Grandy adopted it. Luke became the first national coaching director. In 1982, Scott Davidson developed Australia's first élite player development program with the National Development Council. It was used to select and prepare Australia's first National Junior men's team for the Junior World Championships the following year.

In 1983, the President's Cup for players 13-years and under commenced. First presented in Adelaide by national president, Phil Ginsberg, it was renamed in his memory after his death. That year, Australia competed at the Junior Worlds (U20) for the first time, again the next year, and in 1987. But the National Junior Team disappeared from the international scene for over a decade having lost all games.

The international tournament for youth (U18) on Australia's side of the world began as the IIHF Asian Oceanic Championship in 1984. It was played annually until merged with the Under-18 Worlds in 2002. Jim Fuyarchuk and John Botterill coached the first teams, and Australia qualified for the Worlds in 2003, five years after they began.

Meanwhile, the quota of NSW Superleague imports dropped from eight to four by 1984, and the national association spoke seriously of returning ice hockey to the Olympics in Calgary in 1988, although they were ultimately unsuccessful.

The Under-15 National began in 1985, dedicated to the late Kurt Defris AM who promoted junior hockey throughout a long tenure as Victorian state president. The national association decided to present the original Jim Brown Shield from 1963 to the winners of the Under-23 ice hockey championship. In its other life it was the prize of the Senior B Australian Championship for players on the fringe of the Goodall Cup competition.

In 1997, Coach Botterill and others began work on the winless National Junior Team (U20) which laid dormant for ten years. "We thought rather than just jump into the junior world championships, we'd bring these kids to Canada and basically do a three-week tour through good hockey country", said Botterill. "The objective was to come to British Columbia and really have these kids practice, eat, sleep and live ice hockey". With an eye to the future, he purposively chose midget-aged skaters.

At long last, Australia had a junior men's program with a player development system and a national tournament program for each of five age-bands: under 13, 16, 18 and 23. There were no more dropouts after Botterill coached the National Junior Team to its first win against Iceland in 2000. National junior squads have competed ever since.

But, over the inactive years, the National Ice Hockey Development Council also ran down.

AFTER A WEEK TRAINING in Ceské Budejovice, the 12-hour trip to Belgrade invites spent bodies to recuperate, wired minds to unwind, before reassembly for the task. Small comforts are big, the long adventure in transit almost as gruelling as the adventure of the world stage itself. Jobs abandoned for unfamiliar gate lounges, for hotels someplace, they will miss the cash, the language, the nutrition and sleep, amid all this, God's promise of a patch of iridescent white is heavenly respite.

Their opponents will be mostly pro, paid to play. They will have slept the good sleep, will rise to a good meal, stretch like a drawn bow, like an arrow to a heart, fine-tuned to the finesse of the game, their season peak, to face the Lucky Country, where the season peaked 7 months ago. A relegated Croatia, a China who played together in Finland for 6 months, trained for 2 more in a camp intended to deliver them to the next Winter Olympics, which they will host in Beijing.

But here, at last, far from home, Australians receive respect for who they are, not pity for disadvantage, nor for staring down adversity. Respect for arriving for the 36th time, for flying their colours, for enduring the ineffable lessons that accrue to the underdog. On a bad day they will be difficult to play. On a good day, they will be equals among hockey nations. On every day they will shoulder hope from a remote corner of the world. They will raise your anthem, raise their sticks, raise the bar, raise the questions—What better game? Are you not entertained?

"White City", where the Sava River kisses the Danube, is not a pretty capital but its gritty exuberance makes it one of Europe's cradles of cool. There in the wee hours of the morning the Australian Men's Ice Hockey Team posted a determined 3-2 win over the home side Serbia, to lift itself into second place in the World Championships after two rounds.

On the road to Belgrade, Australia lost Kai Miettinen to training injury, flew in Bert Malloy, then battled themselves in the opening game. So far it's been a tournament styled with the same grit and exuberance that has come to define modern Belgrade itself. In the grandiose coffee houses and smoky dives of the city where the home side has just fallen, talk will turn to hockey. And, against the tide of opinion separating the Australian game from the rest, the Mighty Roos once again contemplate their arrival within striking distance of Gold, and promotion to Division 1 for just the third time in history.

Like most of Belgrade's post war architecture, the Hala Pionir ice hall is not a pretty building, but it is somehow at home tucked in among the blackened facades, cracked and crumbling flagstones, and out-of-date infrastructure. This city ignores the millennia of tumult, from Attila the Hun to Sloboden Milosevic, much like the mortal combatants on the shimmering sheet of ice that is usually crowded out with party skaters.

While the triumphant strains of Advance Australia Fair still echoed through the empty hall overnight, wounds were re-dressed to air, limbs stretched and pressed, minds freed from the hyper focus of assault. The emergency over, the thrill gone, the sudden jump-start that produced the most efficient version of these players abates. Blood flows from critical organs back to the rest of the body, hands shake, legs feel weak, the ability to feel pain returns.

Spain has fallen, a 0-4 shutout. The space between dream and reality at the top of the table of the Division 2A Ice Hockey Worlds is now Australian occupied territory.

By 2019, about one quarter of Australia's four thousand ice hockey players were players under the age of 21. Back when Australia returned to the World Juniors after an absence of 13 years, the team won their first ever international match. Overall they have won only twenty-eight percent of all their games from seventeen Worlds appearances. Ranked 20th in the world when they started, they were ranked 31st by 2015. The National Youth Team (U18) were ranked 34th in the world from thirteen appearances by 2015, which is about where they started. Both have now been participating internationally for well over three decades.

Although today's national junior tournaments were set up in the 1960s and '80s, [16] the ethos that drives them has evolved for well over a century, from the first schoolboy encounters with North Americans in the 1900s, through the first junior inter-club competitions in Victoria during the early-1930s, to inter-rink competitions and interstate contests, initially in the two biggest cities, and eventually every State.

Syd Tange witnessed most of this junior history, and no doubt the courage required of Australian juniors of all ages. The grit and authenticity, the bloodline, that cannot be purchased with a travel visa or dual nationality. It is after all an inheritance. The spirit and culture of Australia.

So, it's a battered old suitcase to a hotel someplace, and a world competitiveness we must master. Australia's national junior and youth squads matter for as long as we want our national senior team to be populated by Australian-born players.

Yet, there is also clear evidence that a good deal more is involved in a world class junior development program than participation in national and international tournaments. The formation in 2012 of a national junior league, as a prerequisite to Australia's continued participation in the World Juniors, is one good example. So are renewed attempts at regional competition, starting across the ditch.

IN THE HEART OF STARI GRAD, people gather in wait from dusk to dawn in Republic Square, ringed by some of Belgrade's most impressive buildings. But a 15-minute walk away, behind a modernist glass façade that mirrors surrounding dilapidation, the Australian men's ice hockey team lie comatose. The city that never sleeps has its share of smoke and mirrors, much like hockey, a zero-sum game until overtime or a shootout produces a win worth less, and a loss worth more.

When the players rise, they will flush wasted leg muscles of lactic acid, the unwanted burn of very soft ice. But the stitched cuts, swollen joints, and separated shoulders some are willing into action will not repair today. Their owners will just chill, wait the last call, while bodies restore a chemical best rendition. Their mental challenge is to stay in the zone, to visualize the end of a road that among their number, only their Captain has seen.

Outside in a Cross-less night sky, some stars burn brighter than others, but that too is deceiving. They just reflect more light from something unseen, something greater than themselves. That's the thing about the souls of good teams, even the brotherhood of man, or the music of the spheres. Whole constellations of star-dust bring order to a mad universe, even though we may only see its glory in the prettiest stars.

China, the Olympic aspirants, lost a chance to stave off relegation, 3-2. On Monday, the Australians will now play a relegated Croatia for Gold and promotion to Division 1.

But they will not win.

__________

Towards the end of his life, Syd Tange wrote the only history of an Australian state ice hockey association and, while mostly anecdotal, it is a significant history. Its dedication reads: To the Pioneers of Ice Sports whose vision and dedication introduced a sport normally associated with the Northern Hemisphere into Australia. [3]

From left: Elgin Luke, Syd Tange, Sid Hiort, John McCrae-Williamson, undated. Birger Nordmark Archive.

ALL-TIME NATIONAL JUNIOR CHAMPIONS (YEAR BY AGE BAND)

[1] World Hockey Summit, Junior Development Around the World, Slavomir Lener, Toronto, 2010.

[2] Sporting Globe, Melbourne, 4 Aug 1928, p 6.

[3] "Ice Hockey: The NSW Ice Hockey, Association Inc. Australia - Facts and Events 1907-1999" by Syd Tange, 1999. Extracts published in 2007 on the IHNSW web site for the 2008 Centenary. Signed copy courtesy Wendy Ovenden.

[4] The Age 20 June 1932, p 4. "Melbourne Grammar Defeat Scotch College". Also see The Argus, Melbourne, Mon 27 Jun 1932, p8 and The Argus, Melbourne, Mon 11 Jul 1932, p4.

[5] Advocate, Melbourne, 21 May 1931, p 31. "The Glaciarium".

[6] The Age, Melbourne, 13 Aug 1907, p 4. "Hockey at the Glaciarium".

[7] The Age, Melbourne, 4 September 1939, p 4, "Junior Players Show Promise", and 25 September 1939, p 6, "Junior Match".

[8] The Age, Melbourne, 23 July 1940, p 4, "Junior Ice Hockey".

[9] The Argus, 3 February 1951, Ken Moses Column

[10] Table Talk, Melbourne, 4 June 1931 p 36.

[11] The Sydney Morning Herald, 29 September 1938, p 16.

[12] The Sydney Morning Herald, 11 Aug 1938 p 16.

[13] Tange, 1999, Ibid. New South Wales Ice Hockey Association, Minutes of Meeting, March 21st, 1923.

[14] Australian Ice Hockey Carnival program, NSW Ice Hockey and Sports Club Ltd, 1965, p 11.

[15] Ice Hockey Week, Official Programme, NSW Ice Hockey Association, May 1961.

[16] A tournament for the 11 and under age band named after John McRae Williamson was conducted between 2003 and 2010, but it became a Jamboree and is no longer a competition.

[17] The Christian Science Monitor, Sydney, 17 May 1982. "Alien sport of ice hockey gains Australian beachhead", by Chris Pritchard.

[18] Image courtesy of Basil Hansen, Ice Hockey Victoria.

[19] International Sports Law and Business, Vol 2, Aaron N Wise, Kluwer Law International, 1999.

[20] Tange Family History papers, Birger Nordmark Archive.