Legends

home

Builder of Australia's first ice rinks from 1904

Pioneer of national Ice Sports

Founder of Ice Hockey in Australia

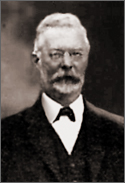

Henry Newman Reid MSE (London) AMIE (Aust.)

1862 - 1947

Edinburgh mid-1800s

ENRY NEWMAN REID, pioneer of national ice sports, and founder of ice hockey in Australia, was the leader of an entrepreneurial syndicate that established Australia's first ice rink in 1904 at 91 Hindley Street, Adelaide, the western continuation of Rundle Mall. Reid's syndicates went on to build the first ice rinks in Melbourne in 1906, at South Gate, and in Sydney in 1907, at Railway Square, Haymarket. His world-class facilities for figure skating, speed skating and ice hockey were built with venture capital over a century ago and produced the first two generations of National ice champions, including his own son and daughter, and many others who represented Australia at Olympic and World Championships. The Melbourne and Sydney Glaciaria were the first and only Australian rinks for 30 years and the Melbourne rink that Reid initially managed himself, cradled the birth of national ice hockey competition, and the national organising bodies for both ice hockey (1908) and skating (1911). The Melbourne Glaciarium is also the story of the first permanent moving picture palace and the birth of the silent film era in Australia.

ENRY NEWMAN REID, pioneer of national ice sports, and founder of ice hockey in Australia, was the leader of an entrepreneurial syndicate that established Australia's first ice rink in 1904 at 91 Hindley Street, Adelaide, the western continuation of Rundle Mall. Reid's syndicates went on to build the first ice rinks in Melbourne in 1906, at South Gate, and in Sydney in 1907, at Railway Square, Haymarket. His world-class facilities for figure skating, speed skating and ice hockey were built with venture capital over a century ago and produced the first two generations of National ice champions, including his own son and daughter, and many others who represented Australia at Olympic and World Championships. The Melbourne and Sydney Glaciaria were the first and only Australian rinks for 30 years and the Melbourne rink that Reid initially managed himself, cradled the birth of national ice hockey competition, and the national organising bodies for both ice hockey (1908) and skating (1911). The Melbourne Glaciarium is also the story of the first permanent moving picture palace and the birth of the silent film era in Australia.

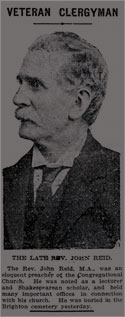

Reid was born in 1862 at Rochester in Kent, 48 km from London, the second son of Rev John Lambert Reid MA (1831–1911) and Mary Ann Mireylees (1831–1918) of Edinburgh. [4, 28, 29, 56, 78] His father was born at the seaport of Scoonie at Leven in Fife, Scotland on October 18th, 1831, the eldest child of Robert Reid (1808–1855), bookseller and printer, and Catherine Lambert. His family immigrated to Melbourne on April 7th, 1855 aboard Ralph Waller. [66] John and Mary Ann remained in Britain until ten years later, having married the year prior when they were both 24 years old, on July 3rd 1854 at St Paul's Edinburgh. [99] John's father, Robert, died six weeks after the family arrived in Melbourne and his brother, Robert Reid (1842–1904), found himself supporting his mother and six sisters from the age of 13.

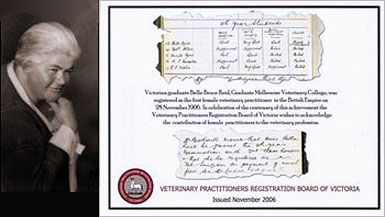

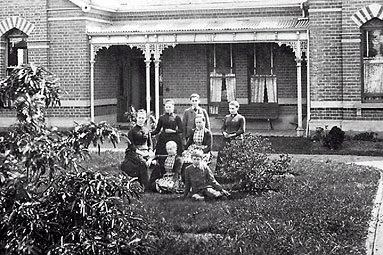

Within ten years, Robert had purchased a cottage and land in Punt Road, Richmond for his mother, paying £111 17/– in June 1864 to Revett Henry Bland, director of the National Bank. Robert married Mary Jane Clancy there on February 2nd, 1865 at the age of 23. They lived at 'Belmont' in Balwyn, then a large rural estate bounded north by Whitehorse Road and south by Mont Albert Road, after which Belmont Park and Belmont Avenue near Camberwell Grammar were later named. The estate was subdivided in the 1930s forming the heritage-listed residential area now known as the 'Reid Estate' including Camberwell Grammar, Barnsbury Road, Salisbury and Walsh Streets, Highton and Palm Groves, and the avenues of Bowley, Chatfield, Crest, Maleela, Myambert, Oakdale, Parkside and Ruhbank. Their youngest daughter, Belle Reid (1883–1945, pictured left), developed her interest in animals from the district's market gardens and dairies. She became the first formally recognized female veterinary surgeon in the British Empire in 1906 and later established the 1,000 acre farm Blossom Park in Bundoora with her sister 'May' (Mary). Belle was inducted to the National Pioneer Women's Hall of Fame in 1996 and the University of Melbourne established the Belle Bruce Reid Medal in 2006.

Henry's father, John, finished his education at the University of Edinburgh and became a Congregationalist preacher and Lecturer on Theology and Philosophy, probably at the Congregationalist College of Victoria at Kew. [69] According to his daughter Agnes and others, he was a learned man; a Shakespearean scholar who spoke several languages, a founder and secretary in 1884 of the Melbourne Shakespeare Society with Professor Morris (principal of Melbourne Grammar) and Dr Neild; a trustee of the Melbourne Public Library (with Morris); and chairman of the Baptist Union of Victoria in 1877; and a councillor at the Working Men's College (now RMIT). [68, 89] John gave his occupation as a "comedian" (probably meaning Shakespearean actor) on the birth certificate of his daughter Agnes, who was born in Northampton, England, on August 7th, 1863. His occupation was listed as a labourer when he emigrated to Melbourne. His brother Robert was a Baptist and also chairman of the Union and its Theological College, established in 1891 at the Collins Street Baptist Church. It is now Whitley College, a residential college of the University of Melbourne in Royal Parade. Robert supported many charitable institutions and was Secretary of the Melbourne Homoeopathic Hospital (1885–1934) in St Kilda Road which later became Prince Henry's Hospital. [76] Henry's mother, Mary Ann was also born in Edinburgh, descended from Robert Mireylees (~1780- ) and Euphemia Dunbar who married in Edinburgh on March 15th, 1799. With the aid of DNA testing, this branch of the Mirilees family has traced its ancestry back four centuries to James Mirrileyis born about 1610, a blacksmith of Pencaitland, East Lothian, who married Elspeth Blair in Ormiston in 1641, about 30 miles east of Edinburgh in the Dunbar Area of East Lothian. [56]

Melbourne, 1864

John and Mary were married on May 3rd, 1854 at Dundee, Scotland, according to one source [4] or at St Paul's, Edinburgh by Rev George Wood according to their Golden Wedding notice of 1904. [99] Either way, they lived in both Scotland and England for a further ten years. John Legg Poore (1816–1867) visited England in 1857, 1858 and 1863 to recruit ministers. He sent out twenty-eight men including Alexander Gosman (1829–1913) who went to the Alma Rd Congregational Church in St Kilda. John and Mary came out early in 1864, the year after Poore's last recruiting drive, on Empress of the Sea, a Black Ball Line clipper built the year prior. Empress was about the same length and two-thirds the width of Polly Woodside. They arrived at Port Phillip (Melbourne) in June that year with their young family: William Eliot, aged 6; Mary Anne, aged 4, Louisa, aged 3; Henry Newman himself, aged 2; and baby Agnes. [29] John became minister of the second Congregational church established in St Kilda, then known as the East St Kilda Congregational Church. It opened on the corner of Hotham and Inkerman Streets in 1865, a year after the Reid's immigrated. The present Church was built in 1887 from which time Henry's younger brothers and sisters lived in the manse. The church is now The Centre for Creative Ministries.

Five more children were born in Victoria between 1864–73: John in 1864 who died an infant in 1865; Alison in 1868; Edith in 1869; Edward Crichton in 1872, and Kezia McCallum in 1873. Another son, Andrew Lambert, was born in 1866 but died in 1889, just 23 years of age. [4, 10, 65] He was a newsagent who began Mildura's first circulating library and was buried on the original Mildura pastoral lease and station established 1847, now The Old Mildura Homestead. [65] Henry's first son (pictured left), born the year Henry's brother Andrew died, was possibly named in his memory. By 1890, Henry Reid had six sisters and two surviving brothers named William Eliot Reid (1858-1939) and Edward Crichton Reid (1872– ), who had moved to Dunedin in Scotland by 1903. [4, 10, 90]

Some histories incorrectly place Henry Newman Reid's arrival in Australia about 1894. [1, 2] In fact, he arrived as a child some 30 years earlier and he had lived in Melbourne for 39 years before he formed the Adelaide Glaciarium syndicate in 1903. He was already firmly established in business circles as a refrigeration engineer and he and wife, Lucy, were raising four children of their own. Henry's grandparents, aunts and uncle had immigrated nine years earlier in 1855. By the time Henry was eighteen, his extended family had history in Melbourne stretching back 35 years and the Reid family name was already firmly established through his uncle, Robert, who had set up Warne & Reid at Collingwood, forerunner to Robert Reid & Co, one of the largest importing busineses in Australia. Its head office was in London by the 1890s with branches in Glasgow, Sydney, Adelaide and Brisbane. Buyers from the London and Glasgow branches combed Europe for softgoods to export to Australia.

Robert was also a major share holder in Buckley & Nunn, the Melbourne department store established in 1851 by Mars Buckley with as fine a reputation as David Jones and Myer. Robert and wife Mary Jane had four sons and six daughters, two of whom married Bates brothers. Agnes Ethel Reid married Edward Albert Bates in Victoria in 1897 [61] and lived at "Maleela", Balwyn, now part of the Reid Estate. Edward was a partner with Bates Smart, Australia's oldest architectural firm — one of the world's oldest — first established in 1853 by Joseph Reed (1823?–1890) as Reed and Barnes. Catherine Lambert Reid married William Edward Copeland Bates in 1892 in Victoria [61] and lived at Larino, in Whitehorse Rd, Balwyn, both becoming directors of Robert Reid & Co and Buckley & Nunn in 1893. The department store is now David Jones next to Myer at 310 Bourke Street, Melbourne, designed by Bates Smart McCutcheon in 1934. [58]

'Larino', the Bates-Reid mansion on the corner of Whitehorse Road and Maleela Avenue, became 'Frances Barkman House' after Frances Barkman (1885-1946) initiated a home there in 1939 for thirty-two Jewish refugee children whose parents were thought to have little chance of getting away from the ever-worsening, even life-threatening, persecution of Nazi Germany. 'Larino' could accommodate 40 children and the first to arrive were sponsored by the Australian Jewish Welfare Society, then dispersed after the war, some to distant parts of the world. Amongst those who remained was George Dreyfus (1928– ), the contemporary classical, film and television composer whose melody Larino Safe Haven was used to mark the 50th anniversary of their arrival in Melbourne. On July 22nd, 1989, Dreyfus provided dinner music at their reunion at the request of the host. The melody was actually written for the innocent scene in the television series Descant for Gossips made by Tim Burstall for the ABC in 1983, where young Vinny is given a dink on the bike by her friend Tommy Peters. Dreyfus has composed numerous film and television scores, including for A Steam Train Passes (1974), Rush (1974), Dimboola (1979) and The Fringe Dwellers (1986). He composed the operas Rathenau in 1993, Die Marx Sisters (1996), and The Takeover (1997). His son is the prominent Melbourne barrister and Queen’s Counsel Mark Alfred Dreyfus QC (1956– ), who was elected to the Federal House of Representatives seat of Isaacs, Victoria, in 2007.

Over the years, the Bates Smart forerunners designed for themselves: Robert Reid's 'Belmont' at Balwyn; Collier Reid Warehouse and Robert Reid & Co Warehouse, 246–50 Flinders Lane; Robert Reid & Co Factory, Hoddle St, Collingwood; Arthur Reid's Residence at Balwyn; Miss May (Mary) Reid's Residence, Sassafras at Belmont, Balwyn; Belle Reid's Blossom Park, Plenty Rd, Bundoora; the Mrs Reid Memorial, Box Hill Cemetery; and alterations to 'Glencoe', later 'Mulberry' c. 1907 at Mornington for Robert's wife, Mary Jane, which she purchased a few years after Robert's death. It was next owned by Agnes Bates (née Reid) from 1925 and is listed on the National Estate, mainly through its association with the Reid family. [73] The practice also designed additional Bates residences; Belmont at Mornington; Barranbak, Boronia & Moore Rds, Vermont; Ranelagh at Mt Eliza; Glen Innis at Bamawn (near Rochester in country Victoria); and the Bates Memorial, Box Hill Cemetery. [72]

The first generation of Reids arrived in Melbourne just twenty years after it was founded. Back in Scotland, Robert Reid had uncles named John, a merchant with ties to South America and Alexander, a master gardener in Angus (Fofarshire). In an 1899 Table Talk interview [59] he revealed one such uncle spoke of a great-uncle also named Robert who had arrived in Australia very much earlier:

"The name of Robert has been long in the family. When at home on his last visit to Scotland, the subject of this biography (Robert) was talking with his uncle, an old man of 86, who said to him, “Your mither’ll no ken wha your’re c’ad after,” and proceeded to relate how Mr. Reid’s great-uncle, Robert Reid, after whom his father had been named, was a bold, buccaneering sort of a character, who ran away from home and joining service with Captain Cook, was present at the planting of the British flag in New South Wales in 1787. To which the grand-nephew replied that he wished his relatives had told him of his wild, freebooting great-uncle on his former visit to Scotland three years before, as he had since been present at the Australian Centennial Banquet of 1887, when the story then and there told would have some point of interest.

“I feel quite as proud of being descended from such a man,” said Mr Reid to his old uncle, “as English people do, who date their origin from the coming over to their island of that Norman Robber, William the Conqueror,” which sentiments surprised the octogenarian much, as he had been designating the Robert Reid of 1787 a “blackguard and a ne’ar-do-well,” but his great-nephew maintains that it is men of such adventurous and intrepid spirit who have made the British Empire what it is, and have laid the foundation of a future colonial aristocracy (the latter used in the best sense of the word) will look back with pride to their brave and glorious forefathers, the first planters of the British Standard on this great Australian Continent, and with it established British speech, laws, energy and enterprise on this side of the globe, all which are fast developing a great southern nation, full of large possibilities and potent influences in the subsequent history of the world." [59]

Capt. James Cook (1728–1779) was the son of a Scottish farm labourer and a Yorkshire girl, not rich or noble parents like most Naval officers of the time. He made three voyages to Australia: Endeavour 1768–71, Resolution 1772–5 and 1776–80. Later, the First Fleet under Capt. Arthur Phillip left England on May 13th, 1787 arriving at Botany Bay between January 18th and 20th, 1788. On the 26th, with the entire fleet anchored in Port Jackson, the British flag was raised and Governor Phillip took formal possession of New South Wales. Robert Reid is said to have sailed with Cook, not Phillip, although he could have returned to England then made a subsequent voyage. He is not listed among Endeavour crew nor First Fleet convicts. He could have been among 'Resolution' crew on Cook's 2nd or 3rd voyages or one of 200 sailors, marines and officers who sailed with the First Fleet.

Many 'First Fleeters' were buried at the Old Sydney Burial Ground from 1792 to 1820 and, indeed, a Robert Reed was buried there on October 31st, 1813, aged 50. He was born about 1763 and came Free. 'Reid' and 'Reed' were interchangeable and records of age at death are not always reliable. Nonetheless, the story has it Robert's great-uncle ran away from home as a boy, and the Robert in this grave was aged between 10 and 13 years when Cook sailed his last two voyages. The story may well be true and this is possibly the last resting place of Henry Newman Reid's great-great-uncle who, at the age of 25, witnessed the planting of the British flag in New South Wales in 1787 (actually, January 26th, 1788). [60]

Melbourne, 1876

There is no record that Henry Reid left Australia before 1876, the year he turned 14. [39] His early schooling probably took place at Melbourne Grammar or Trinity College. The Rt Revd Charles Perry cofounded Trinity in 1872 after he established Melbourne Diocesan Grammar School, at Eastern Hill, begun under Richard Hale Budd in 1849, and then the Geelong Grammar School in 1857. Students of the former became Melbourne Grammar School's first enrolments. All three schools were linked through the town's Anglican leaders of the time. From there, Reid could have enrolled to study refrigeration mechanics (physics) at the University of Melbourne, with which Trinity College had been affiliated since 1876, eventually becoming its first residential college. The University was established in 1853 and first introduced Engineering in the 1860s, well before Reid had matriculated. The Working Men's College (now RMIT) did not open until 1887 when Reid was in his twenties, but it had over 900 students at year end, and ran courses in mechanics and physics. His father was a councillor of the Working Men's College for some years. [89] Reid was a member of the London Society of Engineers and could have been educated in London. That was not uncommon but it is more likely he qualified in Melbourne then applied to the London Society for membership prior to the founding of the Australian Institute.

Reid became an Associate of the Institute of Engineers Australia some time after it was founded in 1919. [34] Some think he specialised in valves and temperature controls and applied for several patents. [2] By the time he was choosing a career, the natural ice industry had become big business in the US and Europe, where ice was cut from the lakes in winter and stored during the summer for export. By 1890, the US alone was exporting 25 million tons. There was none to harvest in Australia, except in Hobart where it was used for the first water supply, and so it was very costly to keep food cool. Refrigeration was one of the great engineering achievements of the 19th century and that was nowhere more heartfelt than in the Australian climate. As it happened, Reid was already at the forefront of refrigeration technology. It had been pioneered by another Scot at Geelong near Melbourne, around the time that Reid was born.

In 1837, a journalist named James Harrison (1816?–1893, pictured left) moved to Geelong from Glasgow and set about designing a refrigeration machine. By 1851, he had a working prototype and, typical of Australian priorities, was soon commissioned by a brewery to cool beer. The result was the first ever practical use of a refrigeration machine producing 3000kg of ice per day. Meanwhile, in Sydney, Thomas Sutcliffe Mort (1816–1878, pictured left) was financing experiments by Eugène Dominique Nicolle (1823–1909), a French-born engineer who registered his first ice-making patent at Sydney in 1861. Nicolle and others bought-out Harrison's Sydney Ice Co and established the first freezing works in the world with Mort that year at Darling Harbour. It was later known as the NSW Fresh Food and Ice Company. The seven main apparatuses Nicolle constructed relied, successively, on systems based on ammonia absorption, air expansion, low pressure ammonia absorption and ammonia reabsorption. He was a pioneer in developing these heat exchange systems and the mechanical contrivances by which they were made effective (also see Next Wave).

In 1885, Joseph Fishburn applied for the first Australian ice rink patent on record entitled 'Improvements in and relating to ice rinks'. [17] Then in 1888, the year of the International Exhibition in Melbourne, the engineer Arthur Otto Sachse (1860–1920) and land agent Charles Edwin Jones (1828–1903) submitted specifications for 'A method of producing and maintaining an ice floor for skating and other purposes of amusement'. [16] This patent was no doubt related to the method Sasche proposed to use on the ice and roller skating rink proposed to be located on land of about half an acre with frontages to Grey and Gipps streets in East Melbourne, better known today as St Vincent's & Mercy Private Hospital. This first ever Australian ice rink Prospectus appeared in The Argus newspaper on Monday 27 August 1888. The syndicate patron was landholder and MLC Sir William John Clarke (1831–1897), a patron of science, who had that same month moved his family to Cliveden, a large Italian Renaissance-style town house he had built where the Hilton Hotel now stands in East Melbourne, an area which became the focal point of upper-class social life for the next twenty years. Here was the ice rink to accompany it. The president was George Le Fevre MD MLC, vice president Thomas Bent MP, and provisional directors included Melbourne's coroner Dr Richard Youl, and railway commissioner William Meeke Fehon (1834-1911). The syndicate solicitor was David Gaunson (1846–1909), an old friend of Bent. [100]

Sachse was a mechanical engineer born in Toowoomba, Queensland, who had settled in Melbourne in 1885, practising as a consulting engineer, patents and trade marks attorney and importer. He was also an MP, a director of the Metropolitan Gas Co which later purchased Melbourne Glaciarium, and a University of Melbourne councillor from 1905. He was well-known to Sir John Grice and his circle of early Melbourne ice sports patrons. Sachse was also a contemporary of Reid, and both men married the same year. The ice rink was proposed to be co-located with a public cold store and a roller rink on the first floor. Roller skating was booming. The rinks were each to be 60 ft x 270 ft and the ice rink was no doubt to be modeled on those the directors new worked satisfactorily at London, Manchester, Brompton, Southport and in other large cities in England, and one at the present time in operation in India. [100] There is no evidence an ice rink was ever built at East Melbourne, or anywhere else in Australia in the 19th century. Had it been built it would have followed on the heels of the world's very first engineered ice rinks in England, all of which had been built over the preceding decade. Sachse had patented hundreds of inventions and other oddities by the time of his death at South Yarra in 1920, many on behalf of others. [18] His patent partner, Jones, (pictured left) was an MP, Melbourne city councillor, journalist and owner of the lively People's Tribune newspaper (1883–6), who became a land agent in the speculative boom of the 1880s. He left for WA soon after the Patent application, returning to Ballarat in 1901. He died at Korumburra in 1903, about the time Reid formed his first Glaciarium syndicate. [19]

Reid may have been associated with the 1888 Melbourne ice rink patent although Sachse was a qualified mechanical engineer who could have devised improvements for ice rinks independently. Sachse's patent partner had died the year Reid formed his syndicate, and the pair could have come to some arrangement. In any event, no similar applications were made until 1896 in Sydney, when MacDonald [91] successfully applied to the NSW Department of Justice to patent an invention entitled 'An improved ice skating rink'. That appears to have been an improvement to the method Sachse had patented eight years earlier in Melbourne. MacDonald's patent process continued until 1904 (NAA 1896 Digital Image). [15] Of several hundred patents related to ice making in the National Archives, these are the few directly related to ice rinks.

Melbourne, 1888

Henry Reid and Lucy Marsden (1859–1946) of Hawksburn Road, South Yarra were married by Henry's father at the Congregational Church, Malvern Road, Prahran on July 19th, 1888. [77] The Chapel, as it was known locally, was the first church in Prahran, originally built 100 metres north of Malvern Road on the east side, between 1850–2. It gave Chapel Street it's name and re-opened in 1859 at 246 Malvern Road until it became redundant in the 1970s when the Congregationalist church merged nation-wide to form the Uniting Church. Rev William Moss (1828–1891) was the first minister until 1878. The building is listed on the Victorian heritage register and is now Chapel-off-Chapel, a Council-sponsored Arts complex at 12 Little Chapel Street.

Lucy Marsden was born in 1859 at the copper mining town of Burra in South Australia, daughter of accountant John Rich Marsden and Emily Jane Morton. [86] John Marsden is recorded among the early pioneers of Burra, but the family moved to Melbourne before 1875 where Lucy's sister, Edith Mary (1875–1950?), was born [86, 32, 33]. Reid was aged 26 and a broker buying and selling for others, perhaps for his uncle Robert or the Thonemann family of ASX brokers. The couple had four children between 1889-96: Andrew Lambert Newman, born 21 September 1889 at Hawksburn; Henry Newman Jr. (Hal), born 1891; Leslie Herbert, born January 1894 at Brighton, Victoria; and Lucy Mireylees Newman, born 1896 at Portland in Victoria. [10, 37] Andrew was later mentioned in correspondence related to the Estate of his aunt, Edith Mary Marsden. [32,33] Donald McKnight wrote recently "... Reid had three sons who all played ice hockey albeit in figure skates..." [13] and Sid Tange named Reid's children as Hal, Andy, Les (Snowy) and a daughter, Mireylees:

"The advertisement below announces that a "Great Ice Hockey Match" would be played on Wednesday October 12th, 1904. Names of the players are not known, but four of them would have been Mr Newman Reid's sons; Hal, Andy, Les (Snowy) and Dunbar Poole." [2]

At that time, Henry Sr was aged about 42; Andy was aged 15, Hal (Henry Jr) was aged 13; and Leslie was aged 10. After Hawksburn (c 1889) and Brighton (c 1894), the Reid family home was Locksley, Haverbrack Ave, Malvern; off Glenferrie Rd near the Malvern Town Hall. The first allotments in Haverbrack Avenue were in the second plan of land subdivision in Malvern, sold by agents Munro & Baillieu in 1890. Malvern Central School, the oldest school in the district, was established in 1875 as the Spring Road School, at the end of Haverbrack Ave in Spring Road. Prior to 1875, classes were held in the old courthouse and the schoolhouse at St George’s Church. Sir Robert Menzies (1894–1978), former Australian Prime Minister and founder of the Australian Liberal Party, lived at No 2 Haverbrack Ave from 1966–78 and Malvern was home to many other notable Australians of Reid's time. Reid and Lucy raised their family deep in the heartland of the Melburnian middle classes.

Vancouver 1893

Reid's uncle, Robert, was 'a foremost Australian commercial magnate', and spent a good deal of time at his London headquarters. He was president of the first Congress of the Chambers of Commerce in Australasia during Victoria's centennial exhibition. He had represented the Melbourne Chamber of Commerce at the Indian and Colonial Exhibition (1886) in London and he was a commissioner at the Paris Exhibition (1889) when he received the cross of the Légion d'honneur [pictured left]. Robert was president of the Melbourne chamber in 1888-90 and 1899-1902. It had been founded in 1851 by William Westgarth (1815–1889). Like the Reids, Westgarth was born in Edinburgh, son of John Westgarth, a surveyor-general of customs for Scotland. The Westgarths were a landed family in a Durham, England, and William was educated at high schools at Leith and Edinburgh and at Dr Bruce's academy at Newcastle upon Tyne. He first worked with the mercantile firm of G Young & Co of Leith, the seaport of Edinburgh, which had Australian interests. He arrived in Melbourne in 1840 then published 'Australia Felix; or, a Historical and Descriptive Account of the Settlement of Port Phillip' (Melbourne) in Edinburgh in 1848, which he republished in England when he visited Britain in 1853, the year before the Reid's immigrated. Westgarth quickly became prominent in London as an old colonial hand and finally succeeded in founding a Chamber of Commerce there in 1881. Reid and Westgarth shared more than a few interests including the London and Melbourne Chambers and city sanitary conditions. In 1883, Westgarth had sponsored a prize and wrote the introduction for papers published in 1886 which included 'Essays on the Street Re-alignment, Reconstruction, and Sanitation of Central London'. A few years later in 1888, Westgarth visited Melbourne for the last time, and Robert Reid was a member of a royal commission into its sanitary conditions.

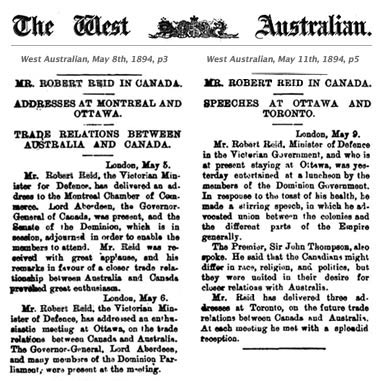

In the years preceding his nephew's rink syndicates, Robert was a member of the upper house (Senate) of the Victorian Legislative Council as a Free Trader from 1892 until he resigned in February 1903, the year before he died. He became Minister for Defence and Minister for Health. He lost his ministerial positions in 1894, but was re-created Minister for Health and also Minister for Public Instruction in 1902. On 21 January 1903, he was appointed to the Australian Senate for Victoria to fill the vacancy caused by the death of Senator Sir Frederick Sargood. Although he refused the position of agent-general in London through pressure of business, the government charged him with explaining the colonial financial situation to help to restore credit there. Robert also persuaded London shippers of the importance of refrigeration, before returning through North America. [57] Amongst his commitments there, he gave a lecture in 1893 at Vancouver, British Columbia, as the Honorable Robert Reid, Minister for Defence and Health from the Colony of Victoria Australia. [58] Five years earlier in 1888, Stanley Park in Vancouver was officially opened by Governor General of Canada, Lord Stanley of Preston (1841–1908), in whose honour it was named. Vancouver was quite small at the time but it was also one of the fastest growing Canadian cities. So, as it happened, Robert visited Canada on official government business, promoting shipping refrigeration in London en route, just ten years before his nephew, Henry, set up the first ice rink syndicate.

Canada was most famous for one thing in 1893. The year before, Lord Stanley had recognised there was no trophy for the best ice hockey team there and purchased a decorative bowl for that purpose. In 1893, there were almost a hundred teams in Montréal alone, and leagues throughout Canada. The donated cup became the world's first ice hockey trophy that year, the Dominion Hockey Challenge Cup, now more famously known as the Stanley Cup. Lord Stanley was buried at Saint Mary's Church, Knowsley, Lancashire, England and was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame as a Builder in 1945. Vancouver surpassed the provincial capital of Victoria in size in 1900. In 1911, Denman Arena opened; Vancouver's first mechanically frozen rink and one of Canada’s first. It was located on the corner West Georgia and Denman flanking Stanley Park. It held 10,500 people, making it one of the world’s largest arenas of its time. It burned down in 1936 after an explosion at an adjacent Coal Harbour shed, but it was home to the Stanley Cup when the Vancouver Millionaires, the city's first hockey team, reigned in 1915. The Vancouver Glaciarium opened in later years. A few months later in May 1894, Reid was addressing the city authorities at Montreal, Ottawa and Toronto, attended by Lord Aberdeen, the new Governor-General of Canada.

The year Reid visited Vancouver, Victorian shipowner James Huddart opened his shipping service between Vancouver and Sydney, Australia. This and the Pacific cable that followed in 1903 increased contact between the two dominion countries. The year Reid returned to Australia, John Short Larke (1840– ) became Canada's first trade commissioner following a successful trade delegation to Australia led by Canada's first Minister of Trade and Commerce, Mackenzie Bowell. Arriving in Sydney in 1895, Larke was tasked with developing the market for Canadian products in Australia, developing a list of Canadian suppliers for promoting sales to Australia, and reporting back to Ottawa regarding market conditions. Trade flows increased and Larke's presence also gave Edmund Barton a confidant in federation debates. His descendants founded the large car-dealership Larke Hoskins. On a diplomatic mission for Australia, Robert Reid was received by the Governor-General Lord Aberdeen, and probably his predecessor Lord Stanley, and the occasion may well have been a definitive moment in the rink development plans of Robert's nephew, Henry. Henry was well-connected to both Melbourne business and State politics through Robert, but it didn't stop there. Robert Reid had his head office in London; a branch office in Glasgow from where Henry's associate, Dubar Poole, migrated in 1899; and branches in the three States in which ice rinks were proposed; Adelaide, Melbourne and Sydney.

Portland Victoria 1896

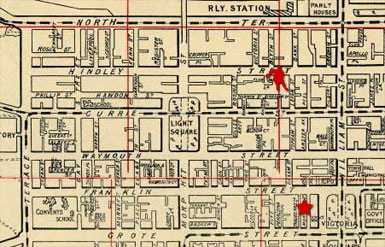

Reid had been in the refrigerating industry since 1879 in which time he had been appointed by the Victorian Government to report on freezing works in that State. [90] He became the advisory director of the Portland Western Districts of Victoria Freezing Company by 1902, a position he had probably held since it was established in 1896 (his daughter was born at Portland in Victoria that year). He later became secretary of the company. In July 1902, he appeared as an expert witness in a court case — Melbourne Chilled Butter and Produce Co Proprietary versus Charles Arthur MacDonald (1867–1957), trading as the Adelaide Ice and Cold Storage Company — where he gave evidence in support of MacDonald. [93] MacDonald of 63 Pitt Street in Sydney, was a Scot; an engineer who went to America when he was young, and "took a leading part in the erection of refrigerating machinery there". He had patented numerous refrigeration inventions including 'An improved ice skating rink' in 1896, when Reid was at Portland, which appears to have been an improvement to the method Sachse had patented eight years earlier in Melbourne. MacDonald was the owner of the Hercules Refrigerating Machine patents. He sold hundreds of the machines in Australia from 1895. By the turn of the century, it was said ninety per cent of the whole of the freezing machinery in Australasia consisted of the patent plants supplied by MacDonald's firm, which was also erecting works in South Africa valued at about £100,000. [90] Reid had become the General Manager of MacDonald's Adelaide ice company [90] from 1902 until he left permanently in 1906. It was there, at Light Square in Adelaide, that he developed and implemented the concept for Adelaide Glaciarium, [94] and it was shortly after that he established his own cold storage works in Melbourne. [95]

Notes:

[1] The successful development of commercial refrigeration by about 1880 (see Next Wave) offered a means of exporting frozen meat. The Australian Frozen Meat Export Co established a slaughtering and freezing plant at Newport in 1882. It was acquired in 1896 by frozen meat exporter, John Cooke (1852–1917), as the Newport Freezing Works, and later became Sims Cooper (see former Gilbertsons Meat Processing Complex). Freezing works were established at Geelong and Portland that same year. The Western District and Wimmera Freezing Company began operating at the mouth of Cowie’s Creek in Geelong, on a site later occupied by International Harvesters. The site of Portland's freezing works, the Portland and Western District of Victoria Freezing Co Ltd, was purchased in 1904 by the meat exporters, Thomas Borthwick & Sons.

Melbourne 1903

Henry Reid had the means to come and go from Britain at will. His uncle was constantly shipping between Britain and Australia and had done so for years. In addition to his Victorian Parliamentary duties as Minister for Health, Robert had become a Federal Senator for Victoria in 1903. [76] For over a quarter of a century, Henry's father, John, had been friendly with municipal and State governors and some of the most significant founders of the church, theatre, art and literary worlds of Melbourne, indeed, Australia and Britain. Those were the circumstances in which Reid met when Poole arrived in Melbourne late-1899, three or four years before Reid formed the Adelaide syndicate. Poole was in his early 20s and Henry Newman Reid was 15 years his senior and very influential. Russell has said that:

'In 1903, Poole sailed from Glasgow to Australia on a windjammer. It is written that, after a stormy voyage of 112 days, the ship finally berthed in Adelaide and there, he found something quite unexpected — a group of ice skating enthusiasts.' [46]

'Loch Garry' did dock at Port Philip (Melbourne) in October of that year with eight aboard including Captain and crew, but Poole was not among them. He may have boarded at Melbourne to travel to Adelaide or vice versa, like other members of the syndicate that year. However, he immigrated on an earlier 'Loch Garry' voyage that arrived at Port Philip in September 1899 with fifteen others. [47, 48] He left Glasgow about May, 1899 and arrived in Melbourne the following September. 'Loch Garry' was a 1,565 ton, three masted ship owned by the Loch Line, formerly the Glasgow Shipping Co. The usual route was to load general cargo and passengers at Glasgow, sail to Adelaide, then to Melbourne or Sydney where they loaded wool or grain, generally for London. The company never changed to steamships, persisting with sail, and consistently ran at a financial loss from 1900. Passengers generally preferred the speed and comfort of steamers and freight rates dropped. The 'Loch' ships usually managed one round voyage to Australia per year and half of this time was unprofitably spent in port, loading, unloading or waiting for cargoes.

Reid had lived in Melbourne a long time yet his rink syndicates were comprised of Scots from Glasgow and Edinburgh or Britons such as the great impresario, Scotsman T J West who was based in Britain. Poole presumably had good reason to leave Britain, more so because he was reputedly the best ice rink manager there. [2, 46] There were no indoor rinks in Scotland until 10 years after he left, nor any in Australia, and so it seems more probable that Poole had worked mainly in England and the syndicate had lured him to Melbourne for his expertise. They needed someone capable and there was a good prospect of Poole profiting from the first indoor rinks in Australia. Reid's connections to Glasgow and London through his uncle suggest Poole's arrival was more than just happenstance; he was in the loop.

Ice rinks were, and still are, more dependent on patronage for commercial survival than most other sports facilities. The bigger their catchment population, the more likely they are to be financially viable. London had an enormous population of 6.5 million in 1900, with most of the modern conveniences we have today — electric light and gas heating, an extensive telephone network, an extensive underground railway network, buses and taxis, a national postal service and metropolitan police force. It could viably support multiple ice rinks and did. There were eleven ice rinks in 1900 and an Act of Parliament had decreed that rinks should be built in all major cities. On the other hand, Glasgow and Edinburgh, the leading cities of Scotland, had been locked into rivalries since at least the eighteenth century. Edinburgh’s population in 1901 was a mere 300,000 or so. It had a reputation at the turn of the century as a staid, climatically bracing, Presbyterian and puritanical city, bristling with well-frequented churches, and peopled with ministers, lawyers, academics and doctors. Glasgow was the opposite with over 750,000 people, drawn both from Ireland and the West of Scotland, it was expanding to become ‘the second city of the Empire’, through industry based on coal, iron, textiles and later shipbuilding.

Melbourne's populace after 1880 doubled in just ten years — the 'Marvellous Melbourne' era. Its streets were first lit by electric lighting in 1894 and the first part of the mains sewage system became operational in 1897. Electric trams arrived in 1905, in addition to cable-drawn trams that had existed since 1885. The city had long had good postal and telegraph services and the first telephone services in Australia had been established there in 1879. It had hosted Test Matches and International Exhibitions and was home to world-class exhibition centres, museums, galleries, libraries, courts and schools. Ornate office buildings up to 12 storeys high rivalled those of New York, London and Chicago. While Sydney was seen as slow and steady, Melbourne was fast and reckless. An ice rink was one of the few things it didn't have.

By 1891 the high times were coming to an end. Banks closed their doors, stockbrokers panicked and thousands lost jobs, homes and savings. Some escaped unscathed but many suffered hardship. It was a dramatic fall, and a far more sober and cautious Melbourne faced the 1900s. When Poole arrived on the eve of the new century, over half a million people were living there and the State itself was home to 1.2 million. In fact, Victoria in 1900 was more populous than Glasgow and Edinburgh combined and Melbourne had created itself in a short 65 years to become the most Victorian city outside London itself. It was and always had been a speculative city, a business enterprise, but Sydney was also growing, exceeding Melbourne's population for the first time in 1902.

Adelaide 1904

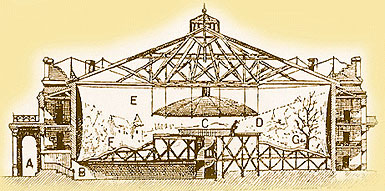

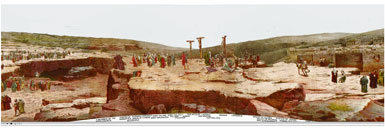

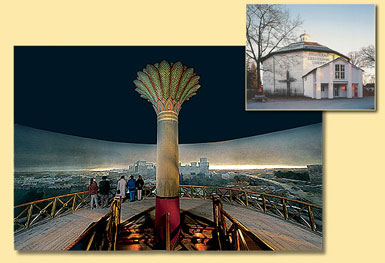

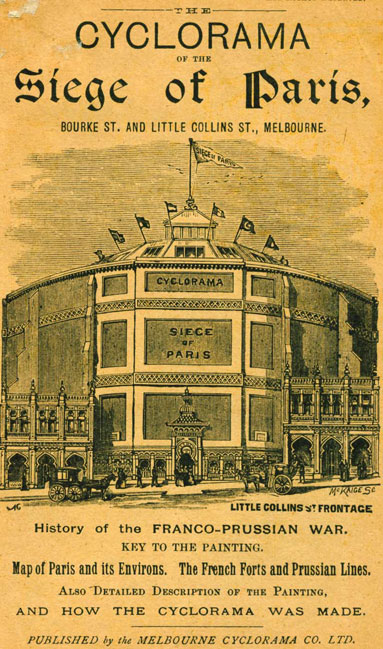

Adelaide, on the other hand, had only just become a state capital. With a population of only 160,000 people, it was one-third the size of Melbourne and Sydney. However, it was there that Reid decided to start, due mainly to the opportunity presented by the Adelaide Ice Works which Reid managed for MacDonald. He chose the Adelaide Cyclorama (1890–99) [31] in Hindley St, by architects English & Soward, for his first rink, and the combination of the two enabled him to produce a rink for about one-quarter the cost of a new building with its own dedicated refrigeration plant. Cycloramas contained a large picture painted onto a cylindrical wall, designed so that it was seen in natural perspective from a platform on which the viewer stood. They were first executed by Robert Barker, an Edinburgh artist, who exhibited one there in 1788. Reed & Gross of Chicago were first to introduce them to Australia in Sydney and at Eastern Hill Cyclorama, which opened in May 1889 on the NW corner of Victoria Parade and Fitzroy Street, Fitzroy. 'Waterloo' was presented in Melbourne and 'The Battle of Gettysburg' in Sydney. Another opened in Little Collins Street, Melbourne in 1891 (image right), on the site that became Georges, 'the store on the hill' (1913). It displayed 'The Seige of Paris'.

The huge painting in the Adelaide Cyclorama was a set-painted copy of ‘Jerusalem and the Crucifixion of Christ’ (1903) by Bruno Piglhein of Munich. It was probably painted by Thaddeus Welch (1844– ) among others, a california landscape painter who studied at the Royal Academy of Art in Munich where he may have met Piglhein. Back in the US, he and other artists painted a cyclorama of the 'Battle of Gettysburg' (1887, Illinois), 'The Siege of Paris' and 'Jerusalem on the Day of the Crucifixion' (1888) before signing a contract to paint cycloramas in Australia in 1889. That very likely included the Adelaide panorama because he was next hired by Reed and Gross, the company who established Australia's first Cycloramas. [64] The Glasgow company Fishburn Brothers held the exhibition rights to Piglhein's panorama and they won a court case preventing it from being exhibited. Manning [31] mentions the hall in which the picture was hung was 39.6m by 35m by 14.6m high and roofed in a single span. It was lit by a central glass skylight.

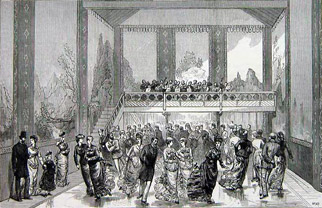

At Regent's Park, London, the Colosseum exhibited panoramas between 1824–75. Like the Adelaide cyclorama, it was surmounted by an immense dome or cupola of glass, by which alone it was lighted. The "Chronicles of the Seasons" (1844), records that the experiment of a skating-hall, with boards for ice, and with skates on wheels, was tried there forty years before either "rinks" or Plimpton's patent skates (1863) were heard of:

"As the exercise of skating can be enjoyed in this country only for a short period in the winter, and sometimes not for many years together near our large towns, an attempt has been made to supply a substitute by which persons might glide rapidly over any level surface, though not with so much facility as upon ice. This contrivance, which . . . . emanated from a Mr. Tyers, consists of the woodwork of a common skate, or something nearly like it; but instead of a steel support at the bottom, having a single row of little wheels placed behind one another, the body of the skater being carried forward by the rolling of the wheels, instead of by the sliding of the iron. We have seen these skates used with much facility on a boarded floor . . . . A more successful plan still has been adopted by an ingenious inventor, who has furnished the lovers of skating in the metropolis with a fine sheet of artificial ice. It was at first exhibited at the Colosseum, in the Regent's Park, but was afterwards removed to a building where a more spacious area could be opened for the purpose. The place is decorated with scenery representing snowy mountains, and in summer it presents, with its parties of skaters, a strange contrast to the actual state of things out of doors."

'Artificial ice' was an ice substitute of hog’s lard and a mixture of salts to provide year-round ‘ice’ skating. The craze had run its course by 1844, as rinkers tired of the smelly ‘ice’ in the Glaciarium, as the venue was often called, and it was not until the 1870s that skating caught on again. The "glaciarium," or "skating-rink" of real ice was the invention of W D Bradwell, the chief machinist of Covent Garden Theatre. He was also the inventor of the artificial ice and first tried it at the theatre. "At first," says a writer in the 'Athenœum', "the surface was hard and polished, and bore skating well; but the amateurs complained it would not enable them to cut a figure like real ice, so next year Bradwell invented an ice which cut well with the skate. The affair was on too small a scale to pay in those days." [82] Indoor roller and 'ice' skating started in London in the 1840s in a building that was multi-functional, but primarily a cyclorama for over fifty years. Henry Reid was born in 1862 at Rochester, 30 miles (48 km) from London.

The Adelaide Cyclorama was destroyed by fire in March 1899, nine years after it opened — about the time a panorama with the same name as its own was acquired by Acme Investment Company, owners of London's National Skating Palace between 1902–8. [62] The 'Palace' was also known as 'Hengler's' for a time after its developer, circus proprietor Charles Hengler (1820–1887) who had staged circuses in his permanent theatres in Liverpool (1857) and Glasgow (1867) before his London débute in 1865. Unsuccessful in London at first, he somehow acquired the Palais Royal six years later and converted it into an 'elegant theatre' known as Hengler's Circus. It became the National Skating Palace in 1895, and eventually the London Palladium. The first British Ice Figure and Dance Championship on record was at 'Hengler's' in 1902, the Ladies gold won by Madge Sayers. The Championships were held at 'Princes' thereafter. Adelaide's huge painting may have been spared the fire by the Glasgow company's landmark court case and Reid's syndicate may somehow have been associated with Hengler's — London's National Skating Palace.

By 1904, Reid's syndicate had acquired the Adelaide Cyclorama or rather, whatever had survived the fire and been rebuilt. The Glaciarium proposal was reported in Adelaide's Advertiser, Register and Express newspapers from June 1904 until 31 May 1905. According to Ice Skating Australia, the Advertiser reported Australia's first rink opened Tuesday, September 6th, 1904. It was named the 'Glaciarium Ice Palace'. The Advertiser also reported the rink had electric lighting and seating for 3,000 people (equivalent to the Palais Theatre in Melbourne). [13, 41] The earliest newspaper records of an 'ice hockey' match are dated July 5th and 12th, 1905, in the Adelaide Express and Advertiser. A 'hockey' match on an ice skating rink was also reported in the Advertiser (August 14th, 1905, p. 6e) and in various subsequent newspapers on numerous occasions. [41]

Reid's uncle Robert was holidaying in England in the early part of 1904. He died there at the age of 61 on May 12th, 1904 at St Ermins Hotel, Westminster, four months before the Adelaide rink opened. He was buried on May 16th at Hampstead Cemetery, Fortune Green Road, four miles from the centre of London. Hampstead's views and health-giving springs brought it many famous inhabitants and visitors over the years including John Constable, William Blake, Alfred Tennyson, Anna Pavlova, and George Du Maurier. One of the most impressive graves belongs to Bannister Fletcher, who wrote the manual for architects. Henry was now without his uncle, but Robert's sons and daughter successfully continued the family importing business long after his death. There is also an altar in St Peter's Church in Queen Street, Mornington (Victoria) in memory of Robert Reid. It was established by his wife Mary Jane who purchased 'Glencoe', later 'Mulberry' at Mornington shortly after Robert died. [73]

Charles Hengler was about 20 years older than Robert and he had been buried at the same cemetery 17 years earlier, adding interest to a possible association. They may have both dealt with London's Acme Investment Company and their cyclorama which Reid could easily have shipped. Or perhaps they shared a common interest through Dunbar Poole, reputedly Britain's top rink manager, who could have worked at the National Skating Palace some time during the decade it operated until he emigrated. One of Hengler's touring circuses performed at the circus site near where Melbourne's Glaciarium was later built, and one of his ringmasters, George Benjamin William Lewis (1818–1906), migrated to Melbourne late-1853 after touring Europe with Hengler in 1849–51. Lewis set up Astley's Amphitheatre in Spring Street for equestrian drama and circus. Modeled on it's 1773 London namesake, it was the forerunner to Melbourne's first Princess Theatre erected by George Selth Coppin (1819–1906, pictured left) in 1854. Lewis toured the goldfields with his circus, China in 1859 and back in Melbourne, the troupe appeared at Cremorne Gardens, Australia's first amusement park (1853–63), owned by Coppin who patented his ice and roller skate invention a few years later in 1866. The antecedent for Coppin's park was off King's Road at Chelsea in England near John Gamgee's London Glaciarium (1876), the world's first mechanically frozen ice rink.

Professor John Gamgee (1831–1894, pictured left) was born in the same year and lived in the same place as Henry's father, John. He was born in Florence, Italy, where his family immigrated until their return in 1854, and became a veterinarian and Professor of Anatomy and Physiology at the Dick Veterinary College in Edinburgh. Somewhat eccentric, and an inventor, it is said he invented the roller skate, along with a new preservation method for meat, a refrigerated hospital ship and a "Zeromotor" (1880–4) which involved a perpetual motion machine (which didn't work). Gamgee was a Freemason at The Rifle Lodge No 405 in Edinburgh, their first initiate to become the Master of the Lodge in 1863. His brother, Sampson Gamgee, was a Birmingham surgeon at Queen's Hospital. [81] John Gamgee was once described as 'the greatest genius the British veterinary profession has ever produced', and discovered his artificial ice rink technology while conducting research into meat refrigeration for import from Australia. Both John and Sampson died before their father, Joseph, who remained in Edinburgh until his death in 1895, aged 94, an eminent veterinary surgeon and teacher. But the sons lived and worked in England, like the parents of Henry Reid and, coincidentally, Henry's niece, Belle Reid, went on to become the first recognized female veterinary surgeon in the British Empire in 1906. The Gamgee's younger brother, Arthur, became a Fellow of the Royal Society and has been called 'the founder of British biochemistry'. This is an 1878 description of Gamgee's first indoor rink in the world, from 'Old and New London':

A few hundred yards to the west of old Battersea Bridge, on the north side of the river, are the celebrated Cremorne Gardens, so named after Thomas Dawson, Lord Cremorne, the site of whose former suburban residence and estate they cover... At night during the summer months the grounds are illuminated with numberless coloured lamps; and there are various ornamental buildings, grottoes, &c., together with a theatre, concert-room, and dining-hall. The amusements provided are of a similar character to those which were presented at Vauxhall Gardens in its palmy days: such as vocal and instrumental concerts, balloon ascents, dancing, fireworks, &c.... On a plot of land behind the old Clock-house, and forming part of what was formerly Queen Elizabeth's nursery ground, and on which still exists a mulberry-tree said to have been planted by that queen, is situated the Glaciarium, or realice skating-rink. The rink is the result of Mr. John Gamgee's long and persevering labours to produce artificial cold at a low cost. The rink has an area of more than one hundred square yards, and the ice is about two inches thick. The ice is produced and its solidity maintained by the constant circulation of an aqueous solution of glycerine through a series of copper tubes of a flat, oval section, and which are embedded in the ice. The glycerine solution is kept at a low temperature by means of liquid sulphurous acid, which is constantly circulated, between a refrigerator on the one side and a condenser on the other, by means of an air-pump placed between the two and driven by a steam-engine.... In the Royal Avenue, a turning on the south side of the road leading towards the Royal Hospital, is another skating-rink, having an area of about 3,000 square yards, laid with Green and King's patent ice. [80]

Coppin used his Apollo Music Hall beside the Haymarket Theatre he built at 172 Bourke Street Melbourne (image right) as a roller skating rink in the late-1860s, and opened another in Hines Assembly Room in Adelaide on May 21st 1868, the first in that city. Rinking revivals continued until around 1911; their demise hastened by the coming of the silent movies. Coppin claimed his Apollo Hall was the first music hall in Australia when it opened in July 1952 in the same building as the Haymarket Theatre adjoining the Eastern Market. He went on to establish Melbourne's theatre land but his amusement park also happened to have a cyclorama and it was virtually next door to the Punt Road residence where Robert Reid and his mother lived at the time. Coppin named and developed the seaside town of Sorrento, where he built his country home. He also named Apollo Bay, after his ship, The Apollo. It was Coppin who brought to Australia the first shipment of ice and the first roller-skates (as well as the first equestrian show and the first camels). The refrigeration, skate and theatrical connections between the Reid's, Coppin and Gamgee cannot be ignored. Like the Shakespearean scholar John Reid he always proudly gave his occupation as "comedian". Gamgee's British patents were named "Improvements applicable to the formation and maintenance of skating rinks", probably because of earlier artificial ice patents. They were not at all dissimilar to the titles of the first Australian ice floor patents. Henry's father and Coppin also shared a friend in common, theatre critic James Edward Neild (1824–1906).

John, Neild and others read the 'Merchant of Venice' for charity at "Crofton Hurst", Hawthorn Road, Caulfield, one Friday evening in 1893. [71] Like John, Neild was a founder of the Melbourne Shakespeare Society and president in 1890, the year in which Coppin was master of ceremonies at a public testimonial for him at the Princess Theatre, in recognition of his many public services. The group also included the 'Shakespearean scholars' Francis Joseph Smart MLA, an original partner of the architectural practice Bates Smart, who became head of the practice when Joseph Reed and W B Tappin died, [72] and Councillor James Moloney MLA (1847?–1931), solicitor, Alderman Melbourne city council (1895–1905), Director Melbourne Herald and Weekly Times; and trustee of the Public Library. [77] Nield was also a member of a Bohemian clique that included Marcus Clarke, G G McCrae, Dr Patrick Moloney, father of James, 'Orion' Horne, J J Shillinglaw, Henry Kendall and Adam Lindsay Gordon. These and many actors and artists gathered at Neild's home at 21 Spring Street, Melbourne regularly on Sunday afternoons. All were members of the Yorick Club that met Saturday nights at Frederick Hadden's home in Spring St, the only significant centre of literary interest and achievement in Victoria in the late 1860s and 1870s. Some of the early 'circus' developments like Lewis' Astley's Amphitheatre, were more variety, picture and music hall theatres to which the first Australian ice rinks were closely related, and probably by more than just ideas. They traversed continents, precursors to the ice shows in which Dunbar Poole developed his abilities. When the Melbourne Glaciarium was later established, it was occasionally used for circuses. [3]

The first rink was over 8,000 super-feet of real ice (743 m2). [1, 41] It's ice surface was circular like the space it was in, with a radius of about 15.4m given its area. Its diameter was therefore about 31m but, strangely, it had a central column with a bandstand for public skating sessions, surrounded by upholstered seats on which skaters could rest, all standing in place of the central viewing podium of the original cyclorama. The post is an oddity because the original space had a clear-span roof in order to avoid a central column. The Glaciarium Syndicate or the previous owner probably rebuilt the burnt-out roof using a central support. A post was obviously not considered a problem in the middle of the rink and it worked out less costly to roof. The syndicate may even have preferred the band and seats in the middle rather than the perimeter.

The Adelaide ice pad is more aptly described as an oval doughnut-shaped circuit, with a width of 25m. The minimum size for International hockey matches at that time was reportedly 54m by 23m or 1,242 m2; an uninterrupted oblong shape 1.7 times the Adelaide rink surface. [2] Current IIHF minimum dimensions are 56m by 26m, providing an ice surface of 1,456 m2. The priorities of the first rink design were neither International skating competition or ice hockey. It was not that much more costly to replace the burnt-out roof with a clear-span like the original. The Cyclorama's circular shape was probably attractive to the syndicate initially. In fact, it was a lot like the first experimental rinks in England — indoor versions of the ice ponds of Scotland on which Poole had probably learnt to skate and play bandy, shinty and curling. Yet, even the first skatable rinks in England 25 years earlier had ice pads measuring 50m by 20m, like the Southport Glaciarium that opened near Liverpool in 1879. Manchester and Princes in London were even larger. Reid may have never seen them and none of that appears to have mattered to him to start. Adelaide provided Reid with the opportunity to experiment and test his ice floor mechanics at a skatable scale. Poole got to skate for the first time in six years on the first and only figure and speed skating circuit in the country. With music. It is doubtful he was able to skate between the ages of 22 and 28; fairly remarkable for a man who competed in World Figure Skating Championships just 6 years later.

Charles Arthur MacDonald was clearly a litigious man, and he had appeared in court over his refrigeration plant and patents on more than a few occasions during this decade, including a drawn-out dispute over his arrangements with Reid:

ALLEGED BREACH OF AGREEMENT. PROPRIETORS OF A SKATING RINK SUED. Melbourne. March 11. An action in relation to an alleged breach of agreement in connection with the refrigerating machinery business carried on at the Glaciarium was begun at the Banco Court to-day before the Chief Justice. The plaintiff was Charles Macdonald, and the defendants were Henry Newman Reid and the Melbourne Ice Skating and Refrigerating Company. The plaintiff, who was a manufacturer of machinery, carried on business in Sydney and Adelaide, and the defendant was an engineer in connection with the refrigerating machinery and cold storage. The plaintiff on March 3 entered into an agreement with the defendant Reid, under which the latter was to act as his general manager at a salary of £500 for the first year, £600 for the second year, and £750 for the third year, and was to be allowed his travelling expenses. An understanding was come to that it would be part ot the duty of the defendant to use his influence in promoting and assisting in the formation of syndicates or companies for ice refrigerating and cold storage purposes. One stipulation was that, such companies when formed should purchase the requisite machinery from the plaintiff, and that liberty should be reserved to the defendant to prepare the plans and specifications for such services. Reid was to receive 2,000 fully-paid up shares in the defendant company. Some 1,500 shares had been allotted him, and the other 500 shares were to be handed to him when he had complied with certain conditions. A declaration was sought by the plaintiff that the 2,000 shares were his (the plaintiff's) property, or that they were acquired by Reid as trustee or agent for the plaintiff. The defence was that the agreement existed between plaintiff and defendant, who, however, denied that he was bound by it to give the whole of his time to the plaintiff's affairs. He was at liberty, he asserted, to devote a portion of his time and ability for his own benefit, and not as employee of the plaintiff in connection with the flotation of companies. The defendant said, it was allowable for him to receive for himself personal remuneration, either in money or in shares, for such promotion. The case stands part heard. [92]

Reid lost this court case but successfully appealed in 1907, soon after Sydney Glaciarium opened. The case was heard before the Full Court of the High Court of Australia, where two or more Justices presided:

THE GLACIARIUM SHARE CASE. Melbourne, September 24. In the High Court to-day, judgment was give on the appeal over the Glaciarium shares. In the original action, the plaintiff was Charles Macdonald, of Sydney and Adelaide, and the defendants were Henry Newman Reid and the Melbourne Ice Skating and Refrigeration Company. It was alleged that the plaintiff entered into an agreement with Reid, under which the latter was to act as general manager, and that it was part of Reid's duty to use his influence in promoting the formation of syndicates for ice refrigerating or cold storage purposes. During the time Reid was in the plaintiff's employ he assisted in the promotion of the Melbourne Ice Skating Company and prepared plans and specifications. Reid was to receive 2,000 fully paid-up shares and 1,500 were allotted to him. The plaintiff sought a declaration, that the shares were his property. The defence was that the plaintiff was at liberty to devote a portion of his time and abilities for his own benefit, and that he was entitled to keep the shares. The Chief Justice gave a verdict in favor of thel plaintiff, and the defendant appealed against that decision on the ground that it was against the evidence. The High Court gave judgment unanimously in favour of the appellants. The defendant's contention that he waa not bound to give the whole of his time to the plaintiff's affairs and that he could engage in other work was upheld. When Reid undertook the supervision and erection of a glaci arium he was, the court found, acting in a capacity other than that of a servant of the plaintiff, and he accepted the shares as remuneration for the work so performed. The decision was come to by the court that it was no part of the defendant's agreement with the plaintiff that he was to hand over the shares and the defendant was therefore entitled to hold them. The judgement of the court below was discharged. [14, 92]

Melbourne 1906

The technology of indoor ice rinks is the same as refrigerators and air conditioners except that the refrigerant usually does not cool the ice directly. It cools brine-water, a calcium-chloride (salt) solution acting as an anti-freeze agent, pumped through an intricate system of pipes beneath the ice. Even today, refrigeration load can be 300 tons for an Olympic size rink which are more sophisticated but not that different in principle. The temporary rinks in Edinburgh and Glasgow were comprised a wooden floor topped with rubber matting made from 465km of 8mm rubber pipes, through which a mix of antifreeze and water was pumped at a temperature of -15°C. The ice was added 2mm at a time over six days by spraying the pipes with water (160,000 litres) until it was 10cm-15cm thick. Perfect ice is an elusive formula. Figure skaters like it between -2°C and -3°C, which makes it soft so the ice grips the skate edges and is less likely to shatter under the impact of jumps. Hockey players prefer it colder, between -4°C and -3°C, to avoid slush. Operating the Adelaide rink was difficult because a refrigerant like aqua ammonia had to be piped from the local ice works a quarter of a mile away (pictured left). There were no stand-alone chillers at the rink. Ammonia may not have been practicable through the rink's pipe grid because it was toxic and required special valves and seals. Leaks would have been a more serious problem than brine-water. For those reasons, Ried may have chosen Gamgee's method or an indirect refrigeration system using anti-freeze from the ice works to chill secondary brine-water at the rink. Thousands of gallons of freezing ammonia and probably brinewater were pumped through Reid's pipe network to extract heat from the water of the ice pad and maintain it frozen. Pipes were reticulated 400m between ice works and rink and the system was therefore both expensive and difficult to maintain.

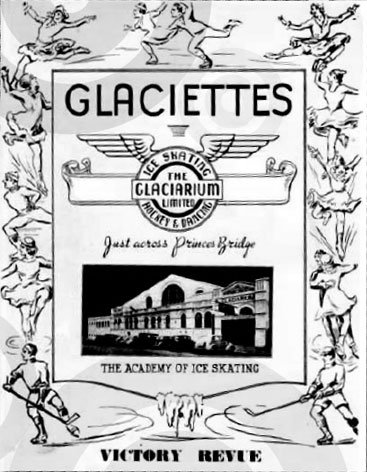

More to the point, Reid had bigger plans. The rink closed in 1908 despite its reported popularity as a favourite and fashionable social venue featuring figure skating, dancing on ice, 'ice hockey' and fancy costume carnivals. The building was converted to an indoor cycling and roller skating track and then the Olympia picture theatre in 1908 by Scotsman, T J West, an early significant cinema entrepreneur who operated in all Australian States, New Zealand and the UK during the early silent days. The Olympia was Adelaide's first permanent picture theatre. [63] His company was known as West’s Pictures and it later became part of the Greater Union Organization. More recently, the original building was again converted to the Grainger Studio, home of the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra (pictured above and left). [13] West continued his association with the 'Glaciarium' syndicates in all three States.

Reid returned home with the rink's refrigeration equipment [21] and so the heart of the original lived on in the Melbourne Glaciarium. Had the Melbourne building survived, even in part, its 'ice floor' equipment would be its primary architectural and historical significance. Sir George Turner (1851–1916) was Victorian Premier at the time the Mebourne rink was planned. Turner served on St Kilda City Council (1885–1900) and was mayor in 1887–88. Reid had grown up in St Kilda and his parents still lived there. Robour tea merchant James Service (1823–1899) had earlier been Premier of Victoria and Mayor of South Melbourne, the authority holding jurisdiction over the Melbourne rink site. His grandson, James Service Thonemann, later played there in the first officially-recognised ice hockey match in Australia. The Thonnemanns were major investors in the Sydney Glaciarium and the Sydney Cold Stores Ltd refrigeration company over which it was built.

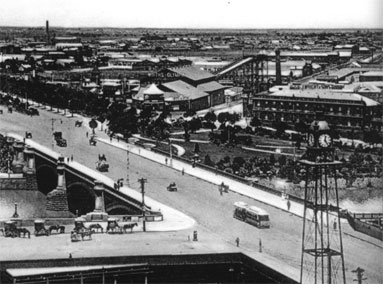

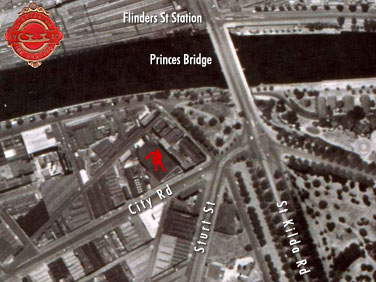

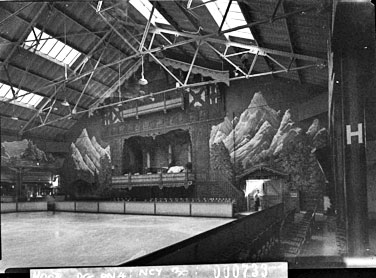

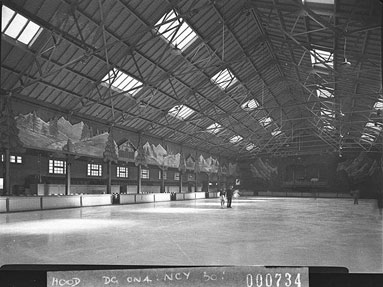

A full-blown rink capable of competitive ice hockey opened in Melbourne on June 9th or 11th, 1906. Gone was the pond-style shape of the Adelaide experiment; with an ice pad of 54.9m x 27.4m, Melbourne was considered the 3rd-largest rink in the world. It was strategically located for prospective patrons across Princes Bridge from Flinders Street Station, which had started in 1900 and was finished in 1910 (Fig 2 below). A 1906 picture postcard (pictured left) shows the rink located next to 'T Craine's Motor Car and Carriage Works, City Road, first street to right over Princess Bridge next Glaciarium'. The precinct was under the control of the South Melbourne (Emerald Hill) municipal association, but it was as close to the heart of Melbourne as possible, a short walk from suburban trains and trams. If you had lived in Melbourne 100 years ago, you could have lived in it's suburbs and commuted to work in the city just as you can today. Nearly all of Melbourne's train system was in place prior to the end of the 19th century, long before the advent of cars. Land surrounding the rink had traditionally been used for circuses and entertainment and old photos even show a roller skating rink. Many of the city's sporting institutions were established around this time or earlier, among them the Melbourne Cup; the City Baths opening in 1903; and the first Australian Open tennis championship in 1905. The Victorian Football League, forerunner of the AFL, had formed in 1897 when Melbourne Grammar and Scotch College played the first match on record.

The ice hockey match officially regarded as the first organised game in Australia, took place at the Melbourne Glaciarium the next month on July 17th, 1906. [1, 2] This is the earliest known Australian record of a specific game of hockey in a specific place at a specific time, and with a recorded score, between two identified teams.

|

'INTERNATIONAL HOCKEY MATCH AT THE GLACIARIUM — AMERICA v. AUSTRALIA

America — U.S.S Baltimore Team — F. G. Randell (captain), R. Stirling, T. H. Miller, J. Benditti, D. F. Kelly, J. T. Connolly Australia — H. J. Blatchley (captain), Dunbar Poole, C. Kelly, J. S. Thonemann, G. Langridge, Salmon The first hockey match — Australia v. America — played on ice in this city, which took place last Tuesday night at the Glaciarium may be marked a complete success, and as the teams had been practising some time, was a good exhibition of the game, and most picturesque. The Australians wore full white suits, the Baltimore boys white shirts and grey trousers. Technically, the Australians were not up to the Americans, but put up a very good game, the result of which was a draw, each team scoring a goal. The sight of the players swiftly gliding and dodging about the ice was very pretty and kaleidoscopic in its changes. Fireman T. H. Miller, of Baltimore, played a magnificent game — in fact, he was the centre of the picture during the whole period of the game — just over thirty minutes.' [36] |

Sydney 1907

The success of Melbourne Glaciarium led to the formation of a Sydney counterpart in 1906, the year the Melbourne rink opened. The company was floated by the Melbourne stockbrokers F Thonemann and Co, key players in Reid's Melbourne eneterprise. [98] Reid remained at the Melbourne rink as manager, whilst Poole left soon after to manage the rink for the Sydney syndicate, South Pole Ice Rink Limited. Its provisional directors were the Hon Sir John See (1845–1907, pictured left); W E Shaw, Managing Director Australian Tobacco; and A H Minter. [22] See was the NSW Premier at the time. He had risen from poverty to commercial eminence and the premiership. Although his experience of public life extended over a quarter of a century, he made no lasting impact on the history of New South Wales. He died on January 31st, 1907 at his Randwick home, six months before the Sydney rink opened. [24] In any event, the provisional directors in Sydney were replaced in August 1906 by Buzzacott, Minter and D Mitchell of Sydney. [98]

Whilst Reid, the syndicate founder, may not have been directly involved with the Sydney rink, the High Court law suit he brought against MacDonald's ice floor patent the year it opened suggests he was. [14] The prospectus reproduced in the Sydney Morning Herald [23] named the architect as J Reid and the engineer as R H Barraclough. Architect Joseph Reed had died in 1890 although he was related by the 1897 marriage of Henry's niece to Edward Bates. John Reid registered a practice as J Reid then John Reid & Son on June 30th 1903, trading at the Equitable Building, 350 George Street, Sydney. [83] John Reid married Minnie F Hubbard in 1889 at West Maitland, NSW and their son, Frederick Bruce Reid, was born in 1890 at Leichardt, NSW. [84] The Bruce name was an ancestral namesake sometimes used as a middle-name in the Reid family, as with Robert's daughter Belle Bruce Reid. The Sydney architect John Reid was quite possibly related to the Melbourne Reids; perhaps the son of one of Henry's brothers or perhaps descended from one of Robert Reid's four sons. Henry's younger brother named John had died in infancy. The engineer was mechanical engineer, Sir Samuel Henry Egerton Barraclough (1871–1958), educated at Sydney Boys' High School and the University of Sydney (BE, 1892). Awarded an 1851 Exhibition travelling scholarship, he attended Sibley College of Engineering at Cornell University. After travelling in North America, where he possibly visited the latest new ice rinks, he returned to Sydney in 1895 and became lecturer-in-charge of the department of (applied) physics at the Sydney Technical College. He published numerous articles over the years, often connected with steam engines and boilers and, conveniently for the syndicate, he had been granted the right of private practice just two years earlier in 1904. [25]

The proposed site for the Sydney rink was 849 George Street West, Railway Square, Haymarket. Railway Square was originally known as Central Square and it was the heart of Sydney's modern retail district in the 1800s and early 1900s. That was due in part to Central railway station and its adjacent hotels, erected to serve country visitors arriving in Sydney by train. The Square was also a busy hub for the electric tramways of Sydney and later a three-platform bus terminal. The syndicate had again selected a site strategically located at a transport interchange; a point much emphasised in old silent movie and vaudeville posters of the time. The Marcus Clark department stores were also located there and a short while later several picture palaces opened, such as the Bijou at 833–5 George Street. Like Adelaide, the site was also occupied by a Cyclorama; probably the first in Sydney that had exhibited 'The Battle of Gettysburg' as Manning recorded. It had imported a Chrono Cinematograph and with the Queen’s Hall in Pitt Street was one of two surviving film exhibitors in Sydney by 1904. Up until then, film exhibitors devoted part of their program to short films and part to live acts such as opera duets, small orchestra pieces, jugglers, tumblers, ventriloquists, canine performers and the multitude of small travelling vaudeville professionals from all over the world. After 1904, the narrative form in film began to dominate and film makers were quick to adapt successful stage productions for film. The NSW Heritage Office notes:

"... by 1909 the Cyclorama had been replaced by Sydney Ice Skating Rink & Cold Storage Co. as well as several shops. It seems likely, therefore, that the building was constructed in at least two phases". [40]

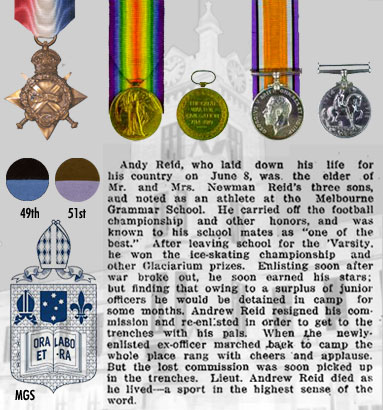

The Sydney syndicate development company was named the same as Reid's Melbourne Ice Skating & Refrigeration Co., except for the word 'Sydney' and a different term for 'Refrigeration'. It is unlikely much of the original Cyclorama was retained in the new rink. The fact that two of the first three rinks actually replaced two of the first three Cycloramas is more revealing. Historians say Cycloramas arrived in Australia in 1889, when American entrepreneurs formed jointstock companies in Sydney and Melbourne with local landboomers and businessmen. However, Coppin's Cremorne Gardens had a Cyclorama much earlier in the mid-1860s of which the Reid's were aware. Some formal association probably existed between Chicago-based Reed and Gross who introduced them, and the rink syndicates that replaced them. Cycloramas were superseded by the silent film era in which syndicate-member T J West, a British-based entrepreneur, was the major player.