Legends

home

A Cool Tradition. A Dream of Champions. Legends of Australian Ice.

Organised ice hockey has been played in Australia for over a CENTURY.

In fact, the ice hockey tradition here is so richly steeped in EMINENCE,

The booming years of MARVELLOUS MELBOURNE,

And the earliest EMERGENCE of the sport internationally,

One wonders how on earth its STORY

Was ever able to be LOST for one whole century,

Like DUST between the cracks of history.

Annie Baker Ford in tennis attire, 1919 and with the first New South Wales Ladies Ice Hockey Team at the inaugural Gower Cup, Melbourne Glaciarium, 1922.

Annie Baker Ford in tennis attire, 1919 and with the first New South Wales Ladies Ice Hockey Team at the inaugural Gower Cup, Melbourne Glaciarium, 1922.

Back row, left to right: V. Wallace, M Ive, Nancy Kerr, Elsie Rea (captain). Front row: J Hall, Annie Baker Ford, Ettie Wallach

(Images courtesy Newcastle Sun, 1919, and Table Talk, Melbourne, 3 Aug 1922)

[ HOCKEY ] Seven Miles from Sydney

Annie Baker Ford (1879 - 1953)

![]() In January 1928, the high-point of post-war prosperity, Dungowan Cabaret Hall hosted the Olympic Ball. This Ball, one of several in Manly’s summer ball season, was held to raise money for local stars to attend the 1928 Olympic Games. One of the organisers was H M 'Harry' Hay, a former Manly swimming star. The Dungowan's summer balls were a highlight of Manly's social season and never failed to attract a lively crowd of Manly's glittering 'young things'. Even as late as 1931 in the depths of the Depression, ads for the Manly Life Saving Club's Lifesavers' Ball at Dungowan could proclaim: "Yes! All the Crowd will be Going!" [18]

In January 1928, the high-point of post-war prosperity, Dungowan Cabaret Hall hosted the Olympic Ball. This Ball, one of several in Manly’s summer ball season, was held to raise money for local stars to attend the 1928 Olympic Games. One of the organisers was H M 'Harry' Hay, a former Manly swimming star. The Dungowan's summer balls were a highlight of Manly's social season and never failed to attract a lively crowd of Manly's glittering 'young things'. Even as late as 1931 in the depths of the Depression, ads for the Manly Life Saving Club's Lifesavers' Ball at Dungowan could proclaim: "Yes! All the Crowd will be Going!" [18]

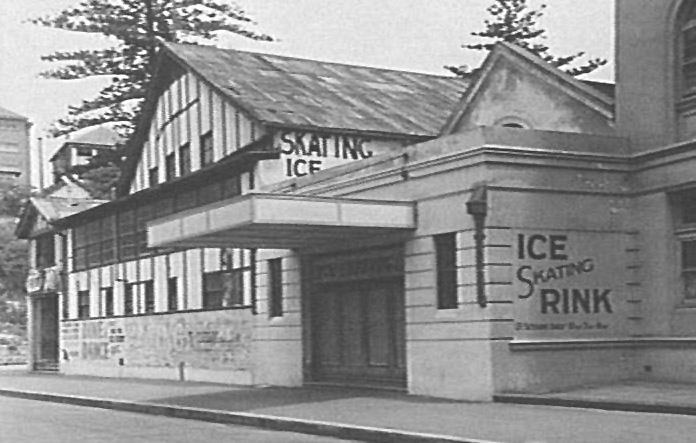

Dungowan Ice Skating Rink, cnr Ashburner St + South Steyne, Manly, 1949.

NY PLACE WITH THE NAME MANLY had no choice in the matter, it was destined to be the home of the iconic bronzed Aussie lifesaver — the heartland of Australia's record of achievement in water sports — even though Bondi Beach is officially recognised as the oldest life saving club in Australia and the world. At the turn of last century, Ashburner Street in Manly, the beach-side suburb of northern Sydney, was an increasingly sought-after ocean and harbour-front location in close proximity to Manly Wharf and the Corso’s thriving shopping centre, stretched out along the curved avenue of Norfolk Island pines that has always defined it.

NY PLACE WITH THE NAME MANLY had no choice in the matter, it was destined to be the home of the iconic bronzed Aussie lifesaver — the heartland of Australia's record of achievement in water sports — even though Bondi Beach is officially recognised as the oldest life saving club in Australia and the world. At the turn of last century, Ashburner Street in Manly, the beach-side suburb of northern Sydney, was an increasingly sought-after ocean and harbour-front location in close proximity to Manly Wharf and the Corso’s thriving shopping centre, stretched out along the curved avenue of Norfolk Island pines that has always defined it.

Back then, this quintessentially Australian ocean beach might equally have belonged on the north coast of France, on the Cote d'Opale, the Boulogne of Australia. A single afternoon could cause twenty to thirty thousand sun-lovers to change into togs in long lines of dressing sheds arranged under the seawall, to bake on even longer lines of hire chairs beneath standing parasols with multi-coloured skirts peeping over the edges. All of it taking place in amongst a bunch of drowsy saddled ponies, donkeys, side shows, and miniature railways.

In 1919, the luxury Dungowan Flats was built at South Steyne, near the corner of Ashburner Street, to house more of those who could afford this privileged location with all the mod cons. Then in the Charleston era, the company converted the Paramount Picture Theatre next door into the Cabaret Dungowan, where grand celebrations were uncorked with sloe gin and jazz. They were no doubt encouraged by London's Bright Young Things, the young aristocrats and socialites who threw fancy dress parties, who were seen in all the trendy venues, and who were well covered by the gossip columns of the London tabloids. Australian Hollywood star, Louise Lovely, appeared there in 1926 following the release of her movie Jewelled Nights, the fiftieth anniversary of Manly’s incorporation was celebrated there in 1927, and the place pulsed with a spectacular series of dance parties in 1928, with such names as the United Charities Ball, Blue and Gold Ball, Rose Day Ball, Life Savers Ball, Masonic Ball, Parachute Ball and the SS Pleasure Ball. [16]

When the magic and decadence of the dance decade ended abruptly in the Great Depression, the Jazz Age also ended. The Cabaret Dungowan became a roller skating rink teaching roller hockey in the worldwide gloom and hardship, and even Prime Minister Lyons attended a Charity Gala there in 1933. After the Second World War in 1949, [14] a short-lived and little-known ice skating rink was the last addition in a complex of buildings extending to the corner of Ashburner Street and South Steyne. The rink opposite the surf club was set-up by the mother of June Weedon, the 1939 Australian ladies skating champion. [15] It ran three sessions daily with skating champions Felix Kaspar and Jack Lee teaching to music provided by Fred Brightfield’s Playboys, and yet it had become a car showroom by 1950.

Eden (far right) at 7A Ashburners Street Manly, Annie's marital home, had lost its original Victorian character by 2015.

At the other end of Ashburner Street — the short, harbour-end a few doors up from the Esplanade — are the vestiges of two late-Victorian terraces more typical of high-density working-class suburbs, such as Glebe or Paddington. The iron lace verandahs try rather vainly to tart up the dross facades of workers' cottages originally occupied by those who serviced the 19th century mansions on the hillsides above. The terra-cotta tiled roofs that replaced the corrugated iron are even more alien.

The house at No 7A was aptly named Eden and the young woman who lived there from about 1915, when Manly was still a village, [13] had turned seventy the year the ice rink opened at the other end of her street. She may well have moved to Balgowlah by then, but there was nonetheless a certain resonance in this order of things. Once hailed "the finest all-round woman athlete in Australia", [8] she was a national tennis and rowing champion as well as a talented swimmer, surfer and horse-rider. One of Sydney's leading figure skaters and seven-times captain of the New South Wales ladies ice hockey team in her forties, she had pursued a sporting career in her youth that was nothing short of spectacular.

Born Annie Kellett Baker on June 15th 1879 at Hay in New South Wales, she was the daughter of police inspector William Thomas Baker and Annie Lawden who married at Deniliquin in 1876 and later moved to Newtown in Sydney. She had four sisters and a brother, Leslie, who was a bank manager at Glenn Innes. Her mother remarried to Rev A R Jones of Wales and lived in America for ten years until his death. [10] Annie was a figure skater at Sydney Glaciarium who became the first honorary secretary of the Sydney Ladies Ice Hockey Club in 1922 [5] and a goaltender who represented New South Wales in Gower Cup ice hockey eight times, all but once as captain. Her back-up keeper in 1924 was Mirey Reid, daughter of H Newman Reid.

Annie was keeper for NSW in the inaugural ladies interstate series at Melbourne Glaciarium. Matches were played in two halves by one line of six players, and two 'relay' or substitute players after 1925. The State ice hockey teams with the most wins from three tests took custody of the Gower Cup until the next series. Writing from Melbourne to a friend in Sydney, she spoke of "the splendid welcome accorded the team of ladies representing the mother State at ice hockey".

Like Annie, team captain Elsie Rea, Nancy Kerr and J Hall were also well-known Sydney figure skaters. "They have shown a sporting spirit in engaging in the matches in Melbourne", wrote the Sydney Mail, "as some of the fancy figure exponents refrain from playing hockey, fearing it might spoil the more artistic department of their sport". The newspaper assured its readers that none of the girls had ever been seriously hurt, "although each one plays a highly spectacular game". The New South Wales ladies won their very first match against Victoria by three goals to nil, Annie with the shutout. The State went on to win the Gower Cup in three consecutive seasons — 1924, 1925 and 1926.

A former lawn tennis champion of New South Wales, Annie had represented her State twenty-two times in tennis, during the early years when the Sydney Lawn Tennis Club blazed the way in NSW with the Interstate Colonial matches and the NSW Championships. The sport had become popular as a social game from its arrival in Australia in the late 1870s and since 1900, Australian men and women tennis players have been ranked as some of the world's best. From 1885 to 1922, when the National Championships ceased to be a men-only event, the NSW and Victorian Championships were the leading events for Australian women. Adrian Quist once wrote that from "an Australian viewpoint, the Championships of New South Wales (Sydney) and Victoria (Melbourne) carry almost the same prestige as the national titles." [20]

Annie played on the courts at the Sydney Cricket Ground which was a popular arena for a whole range of sports before the turn of the 20th century. The Championships were taken over by the NSW Tennis Association and the matches were moved to the Double Bay purpose-built courts in 1911, then eventually White City. [12] Both singles and doubles matches in those days consisted of three sets, not the best of three advantage sets.

In 1906, at the age of twenty-seven, Annie won her first ladies' singles tennis Championship of New South Wales, today's Sydney International, and followed it from 1908 onwards with about 60 more tennis championships in Australian States and New Zealand. She was six-times New South Wales Ladies Singles Tennis Champion in 1906, 1908, 1912, 1916, 1917 and 1918. She was three-times runner-up to Pearl Stewart in 1913, 1914 and 1915. [7] After winning the ladies' doubles championship at Strathfield in 1908, 1913 and 1914, she returned after a five year break, and won the coveted honour for the fourth time in 1919. [3] She was eight times Queensland Ladies Singles Tennis Champion in 1908, 1909, 1911, 1912, 1914, 1915, 1919 and 1920 and she won the ladies singles championship of New Zealand at least once.

In May 1920, New South Wales competed in its first ladies interstate rowing race without success, although the Australian Women's Rowing Council was formed at the regatta, some time before the men's association. Annie was a member of the Sydney Women's Rowing Club which had been founded in 1910 near Abbotsford. She won the Women's Sculling Championship on the Parramatta River in 1922 at the age of 43. She was also a member of the crew that won the champion fours on the same day.

Waving to friends after the finish of the ladies sculling championship which she won on the Parammatta River in 1922. The Referee, Sydney, 15 Nov 1922.

Annie moved to Eden in Manly when she was thirty-two years old, a few years after she had married architect Bertram Willoughby Ford in 1911. [13] Bert was born in 1880 at Concord NSW, the youngest of eight children, and a great-grandson of Archdeacon William Cowper, the first Church of England minister to arrive in Australia in 1809. His great-uncle was Sir Charles Cowper, a member of the first Parliament of New South Wales and Premier on five occasions. [11] The family owned Burrabogie station on the Murrumbidgee River near Hay where Annie was born. Bert's early career was noteworthy for his "eclectic designs of small banks in rural NSW", no doubt facilitated by his family and school networks. [1]

American-style ‘boosting’ emerged strongly in Sydney after the war, and Manly had its fair share of citizens interested in exploiting its potential for becoming the pre-eminent resort of Sydney and Australia. [18] About the time the Fords moved to Manly, the Council of the Town Planning Association of New South Wales was invited to meet there and share ideas for Manly’s orderly development and ‘beautification’. [18] In 1922, the year Annie commenced ice hockey, Bert became a founding member of a new local progress association that called itself the Manly Town Planning Association.

He designed a number of buildings there, including the former Hot Salt Water Baths on South Steyne in 1925. [2] A member of the Institute of Architects, he attended some of the early public lectures of the Town Planning Association of New South Wales (TPANSW); became a council member and honorary secretary in 1931; and then its ninth, longest-serving and last president in 1934. [1, 6] Annie also played a prominent part in the TPANSW [4] and her husband followed the lawn tennis circuit as a sports journalist with the Sydney Morning Herald from 1925 to 1931. [1] She had credited him with much of her success, and considered him "a leading authority on tennis, and a keen judge of rowing." [8]

[Left] Bertram Willoughby Ford in 1934. The Sydney Morning Herald. [Right] Chairing a meeting of the Town Planning Association of New South Wales in a bomb shelter, 1941. TPANSW Annual Report, 1940-41.

Freestone, in his critical history of Australia's town planning associations, was much less generous about Bert Ford's role in the NSW association. [1] He found his public interests varied widely from basic wage increases and the effect on the building trade, to painting the Sydney Harbour Bridge in "old gold". From abolition of the upper house of parliament, to feeding "hungry kookas". He considered his reading of issues was limited and skewed by a deeply conservative ideology. [1] His political affiliation was the United Australia Party, a forerunner of today's Liberal Party on the political right.

Bert headed the Town Planning Association for over thirty years, but his style was neither cooperative nor progressive, and in 1945 he became a strong critic of the restrictive provision's in NSW's first proper planning act. By the 1950s, the TPANSW under him had become a reactionary organisation more often than not opposed to planning, rather than being an informed and independent voice providing constructive criticism. [1] In August 1951, the surviving state entities were folded into a national Planning Institute of Australia.

Annie Baker-Ford died at her home at Balgowlah on June 5th 1953 survived by her husband. She was interred at French's Forest Cemetery. [9]

| NSW Ladies Singles Tennis Champion [7] | |||

| 1918 | Annie Baker Ford | ||

| 1917 | Annie Baker Ford | ||

| 1916 | Annie Baker Ford | ||

| 1912 | Annie Baker Ford | Collings | 6–0, 6–3 |

| 1908 | Annie Baker | Collings | 6–2, 6–2 |

| 1906 | Annie Baker | Gardiner | 6–2, 6–1 |

| NSW Ladies Singles Tennis Runner-up [7] | |||

| 1920 | Annie Halley | Annie Baker Ford | 6-4 6-3 |

| 1919 | Margaret Molesworth | Annie Baker Ford | 2-6 6-4 6-1 |

| 1915 | Pearl Stewart | Annie Baker Ford | 6-4 6-2 |

| 1914 | Pearl Stewart | Annie Baker Ford | 6-1 6-0 |

| 1913 | Pearl Stewart | Annie Baker Ford | 6-2 6-1 |

Citations:

[1] Cities, Citizens and Environmental Reform: Histories of Australian Town Planning Associations. Robert Freestone (Ed.), Sydney University Press, 2009

[2] Manly Library Local Studies Blog. Stories from Manly's past, 14 Jan 2015. An Amazing All-rounder.

[3] The Register, Adelaide, Monday 27 November 1922, p 8. A Champion Woman Athlete.

[4] The Sydney Morning Herald, Saturday 6 June 1953, p 6. Death Of Mrs. Bertram Ford.

[5] Kalgoorlie Miner, Fri 1 Dec 1922.

[6] The Sydney Morning Herald, 14 August 1934, p 16. Mr Bertram W. Ford, Town Planning President.

[7] API International Sydney Tennis website, womens-singles-champions, online. Also Tennis Forum Online The Wikipedia article, Sydney International, is not accurate.

[8] Referee, Sydney, Wed 15 Nov 1922, p 14

[9] The Sydney Morning Herald, 6 Jun 1953, p 6. Death of Mrs Bertram Ford.

[10] Glen Innes Examiner, NSW, 31 December 1938, p 5. Obituary. Mrs Baker Jones

[11] The Sydney Morning Herald, 13 Aug 1937, p 12. Mr B W Ford, Town Planners' President.

[12] Sydney Morning Herald 26th April, 1941. Lawn Tennis Early Development, History In New South Wales, by Dr G H McElhone

[13] Ashburner Street, City of Manly

[14] The Sydney Morning Herald, 18 August 1949

[15] Goulburn Evening Post NSW 9 May 1951 p 2

[16] Dungowan Fact Sheet, Australian Heritage Commission

[17] Manly Daily Wed 2 July 1930, advertisement. Skating taught at Dungowan, Hockey tonight Dungowan versus Daceyville, Direction: Frank Hewett.

[18] Faster: Manly in the 1920s, Terry Metherell, 2006

[19] Sydney Mail NSW 26 July 1922 p 10.

[20] Encyclopedia of Tennis, Max Robertson ( ed.), 1973, p. 201