Victoria, Tange Trophy Champions, 2009. (40th Anniversary, Centenary Year of the Goodall Cup).

From left: Jamie Bourke, Austin McKenzie (Daniel Szalinski behind), Jack Carpenter. Coach Simon Holmes in cap, assistant coach Roy Sargent behind Carpenter.

Before the inaugural Tange Trophy in 1969, "junior" commonly meant B-grade or reserve players, not necessarily players under the age of 21 like today.

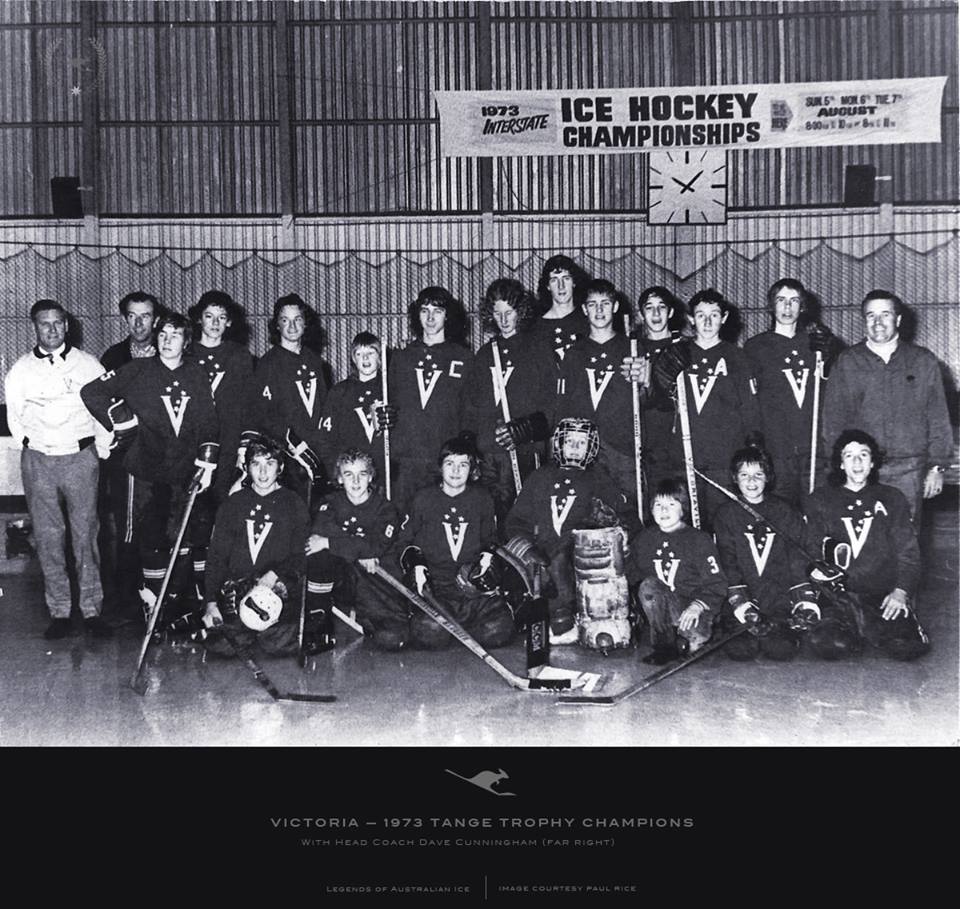

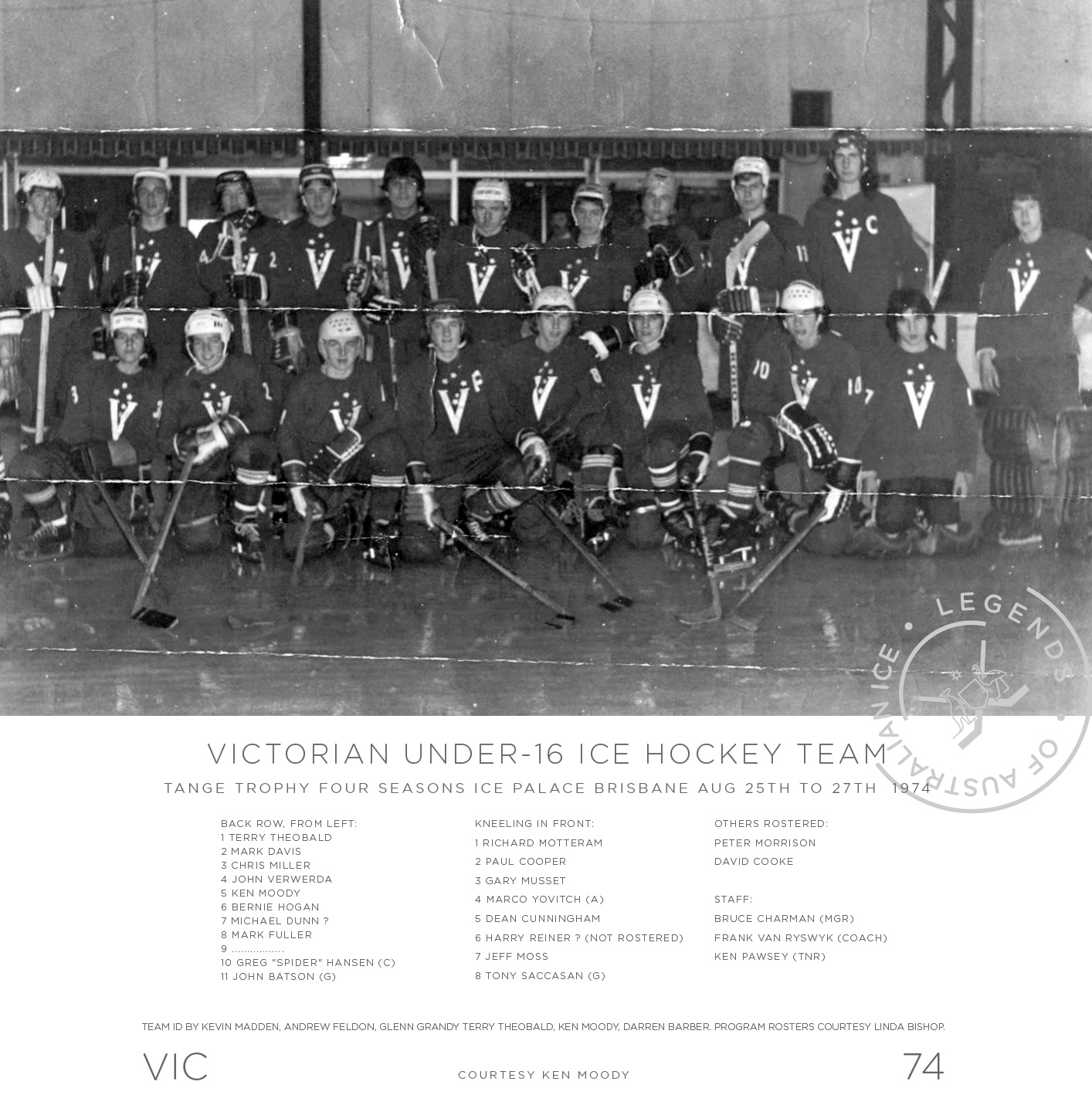

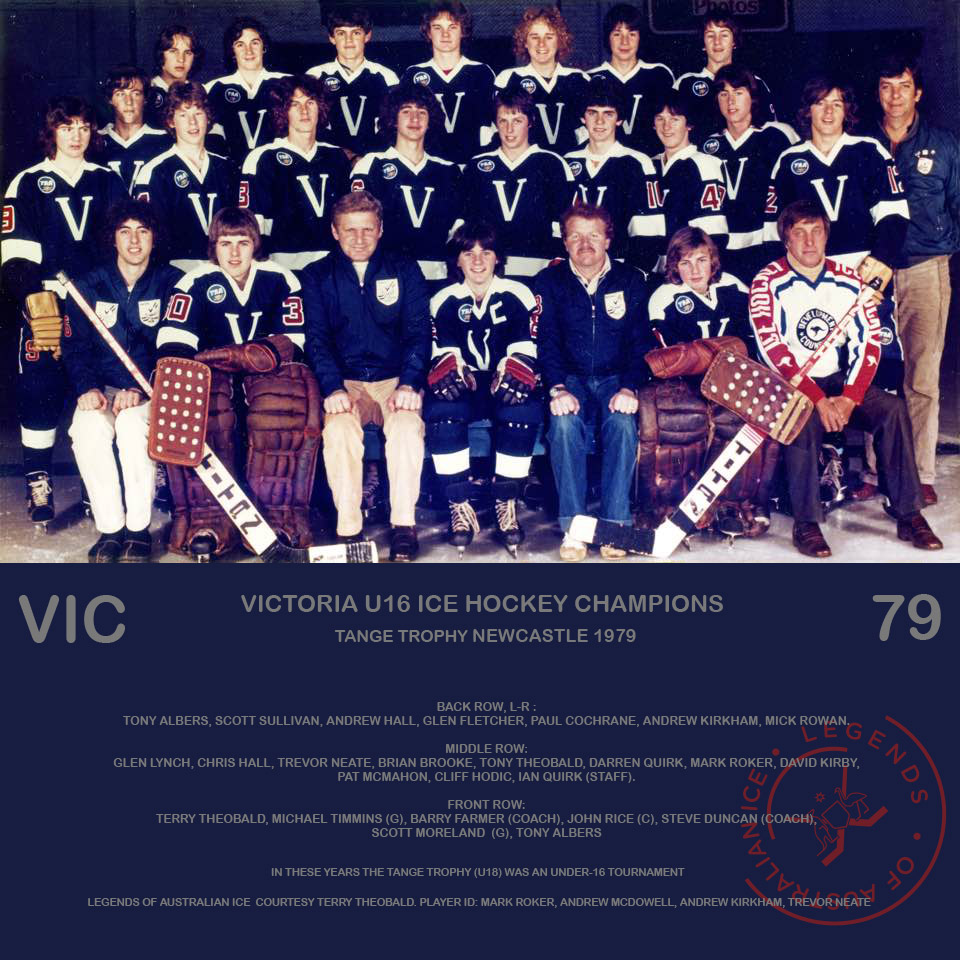

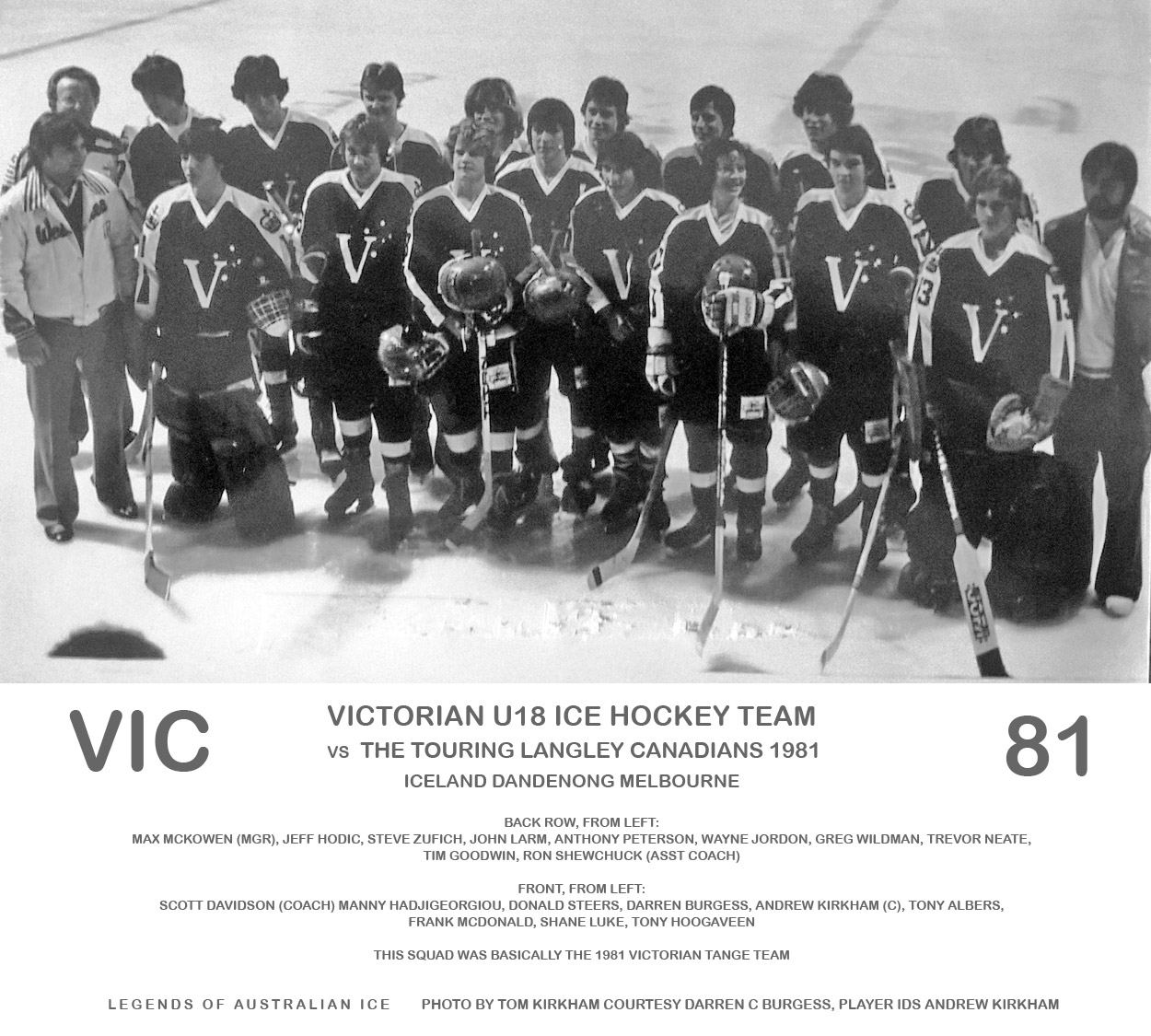

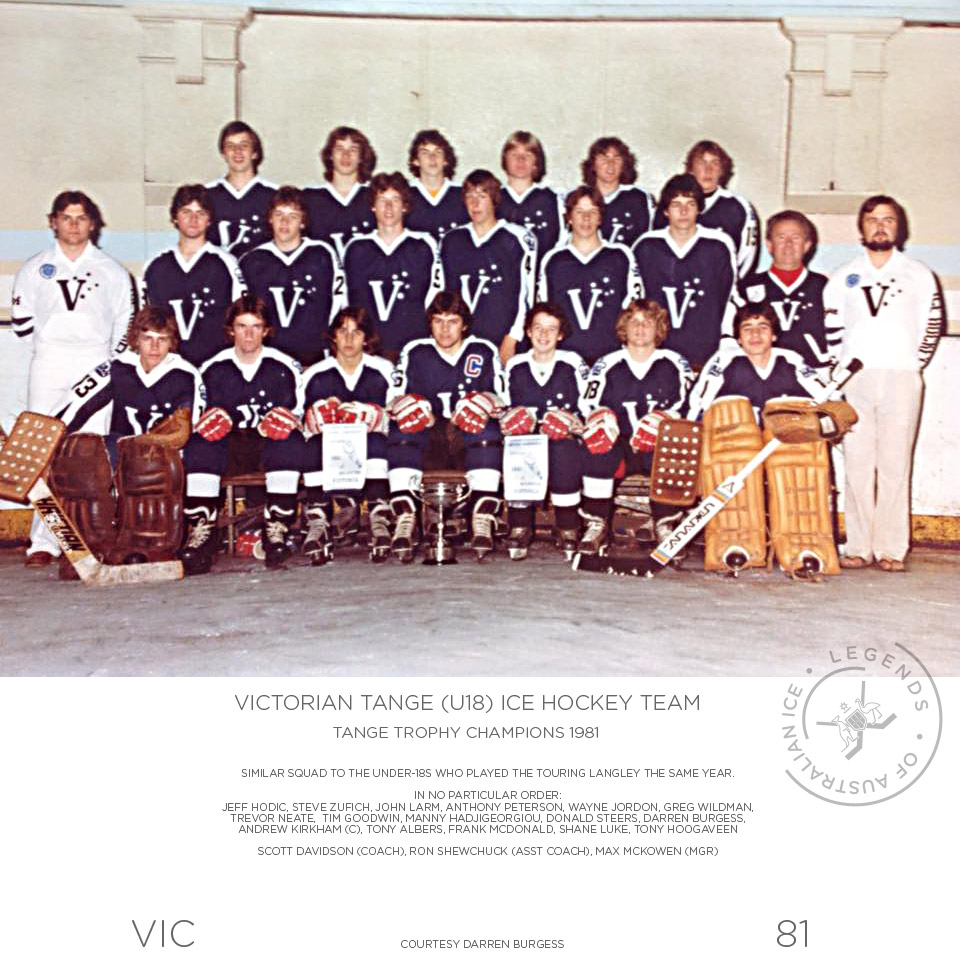

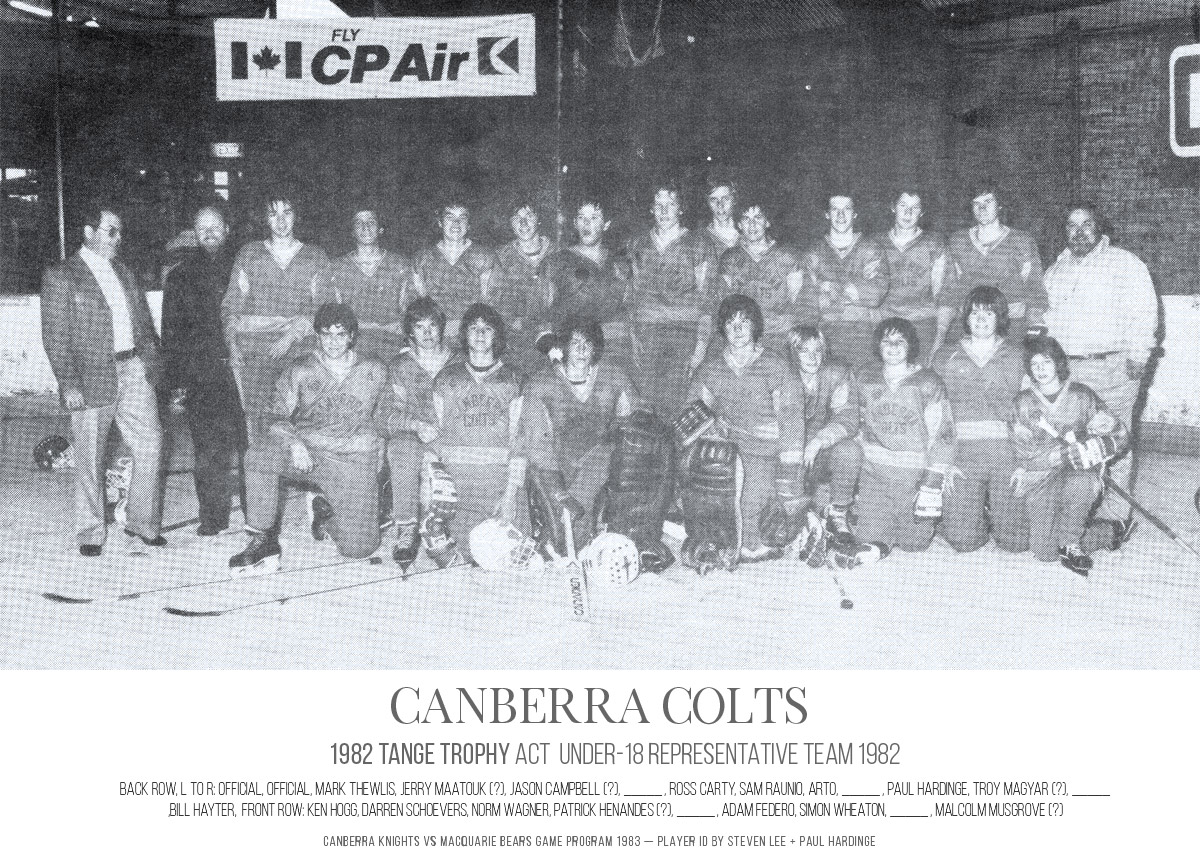

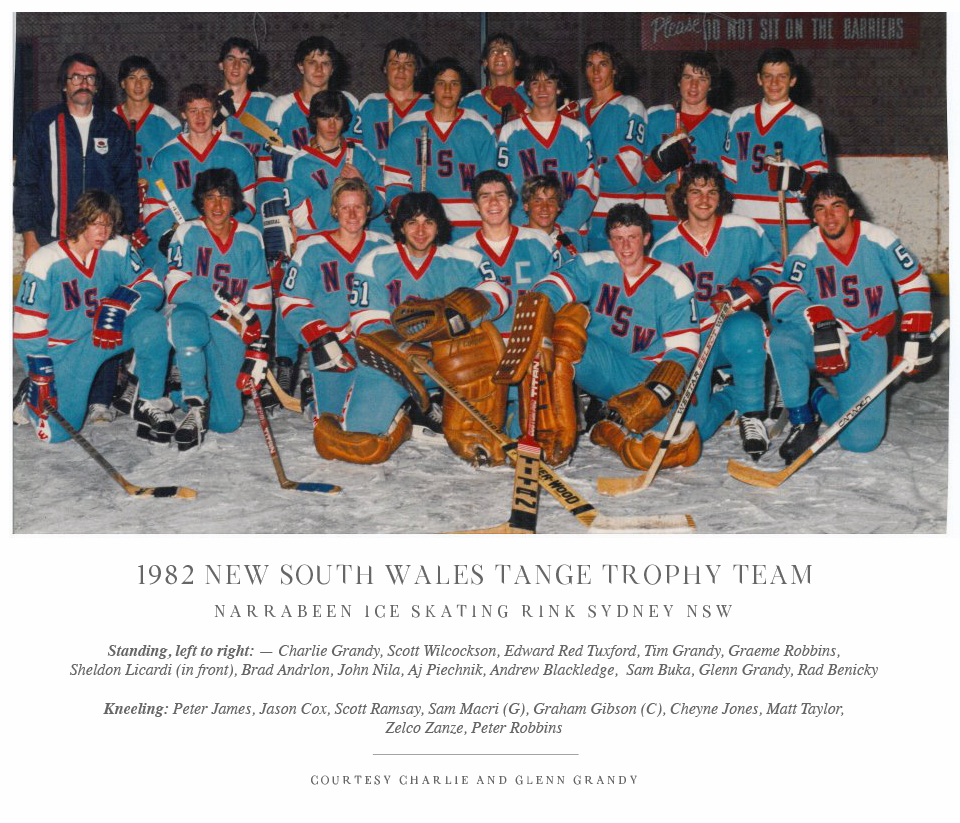

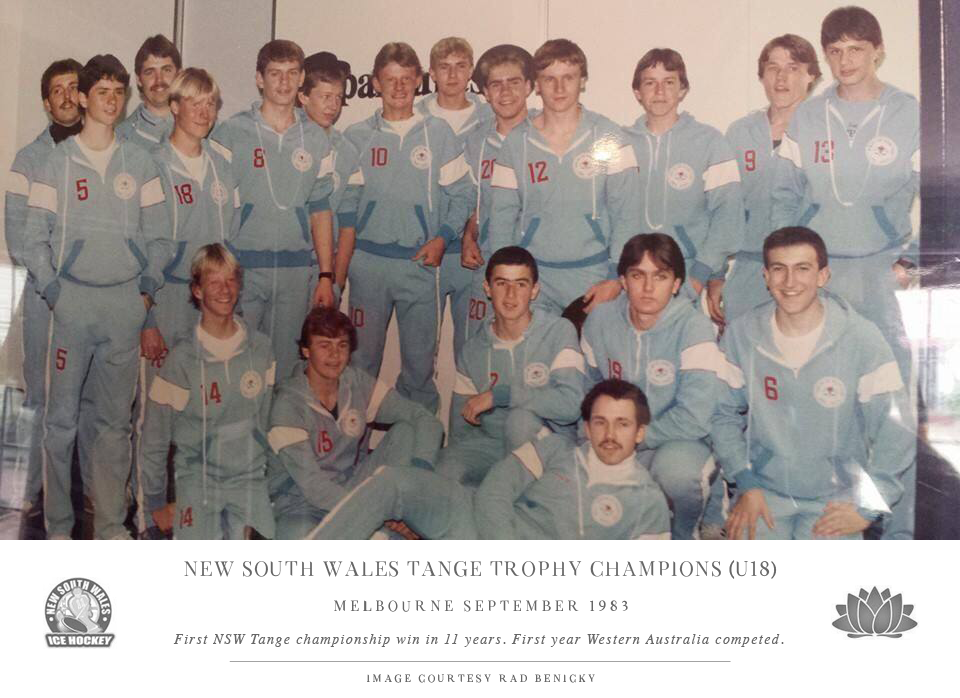

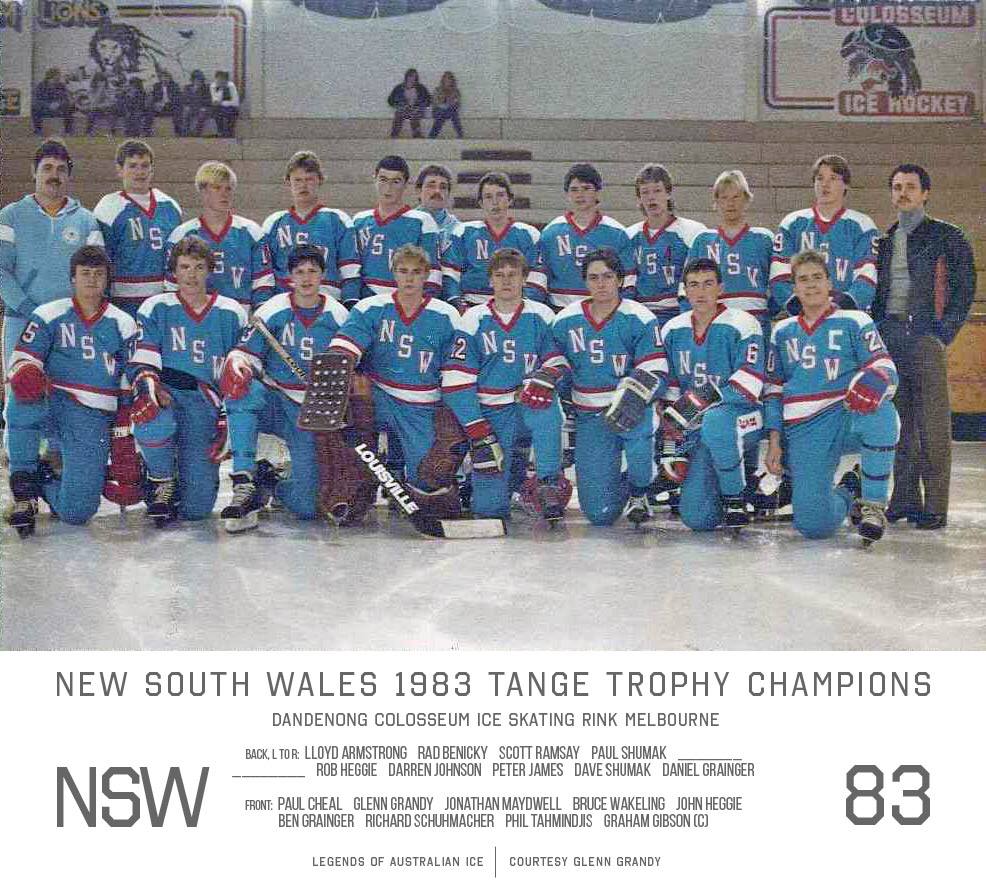

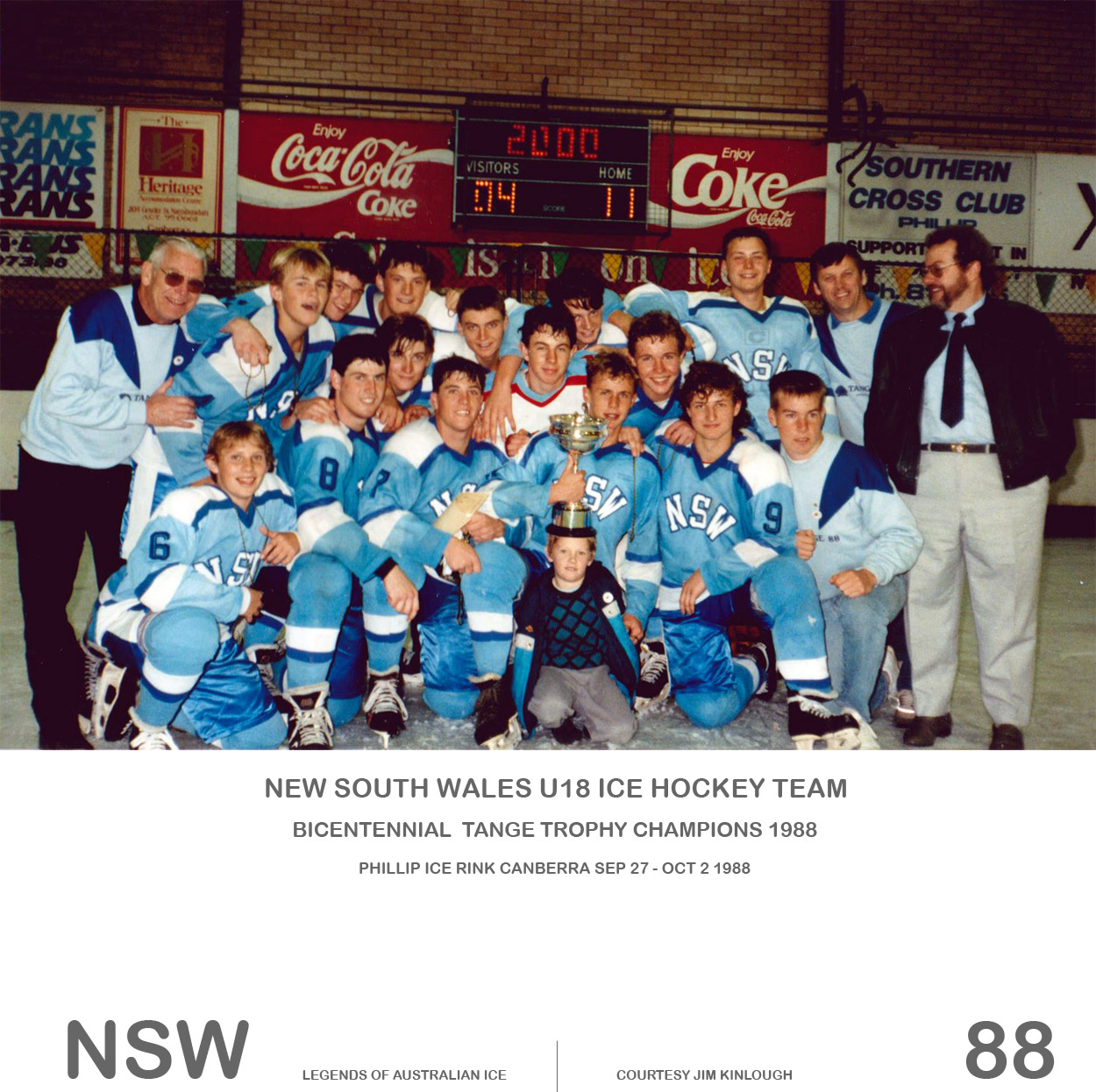

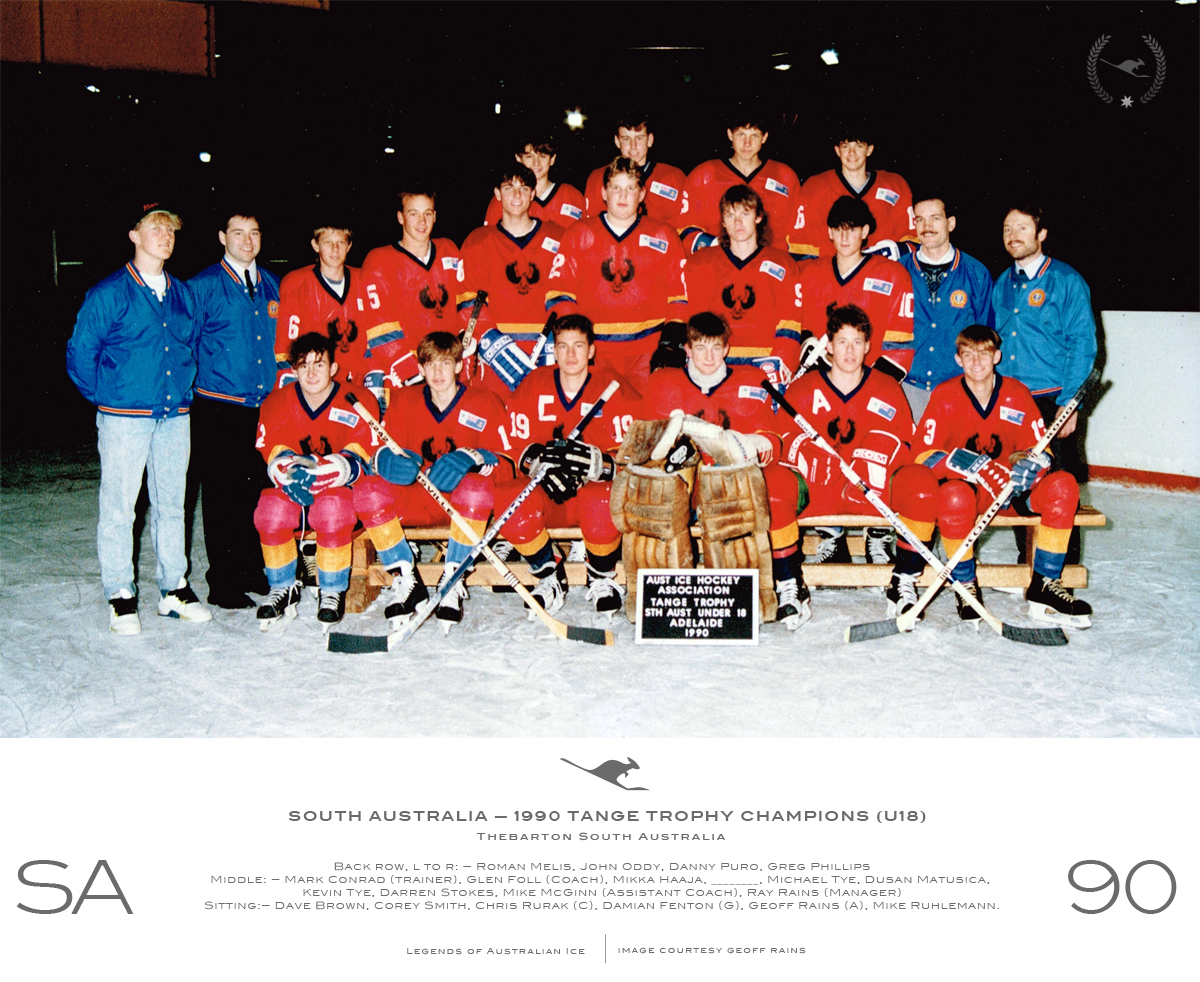

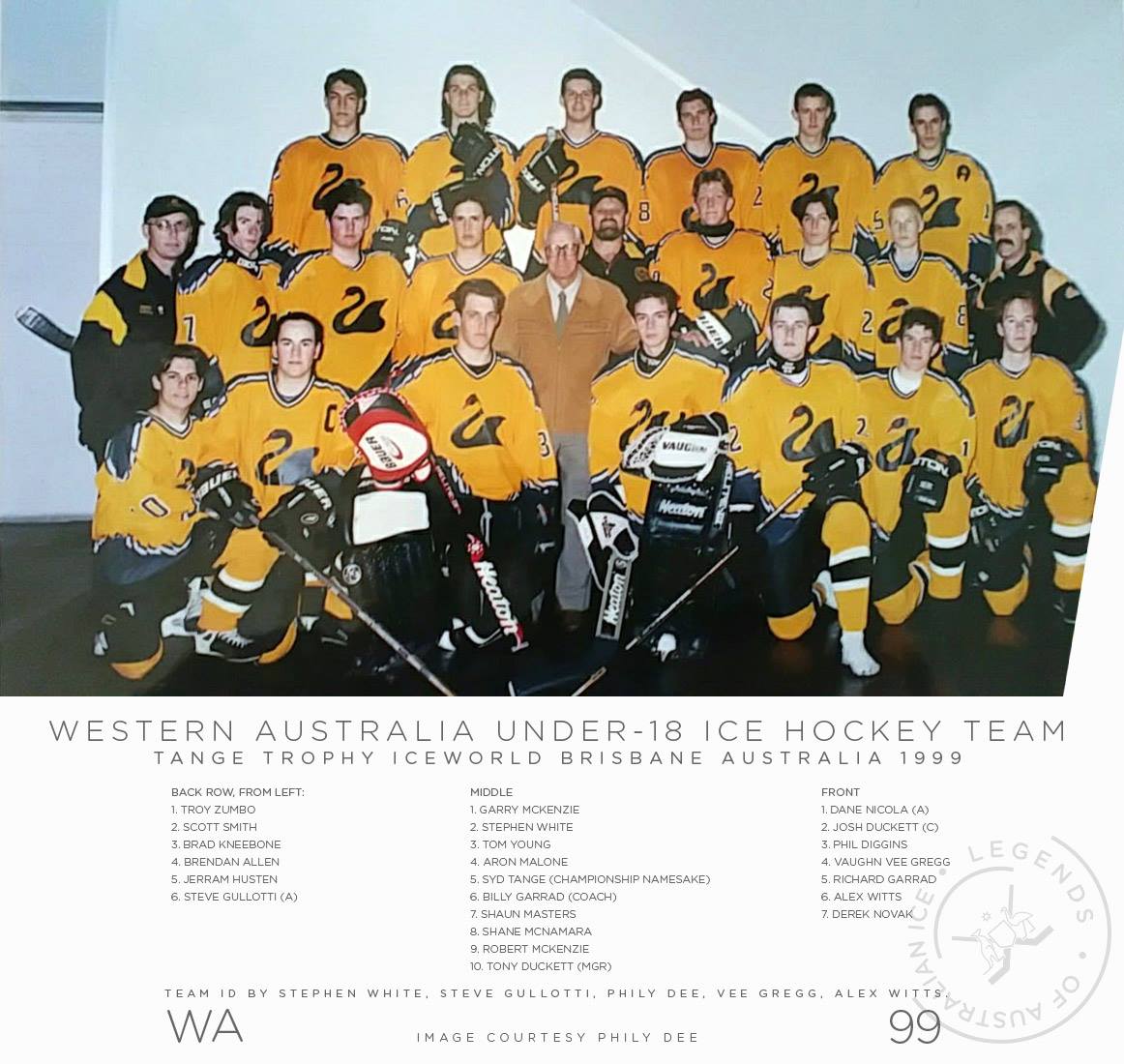

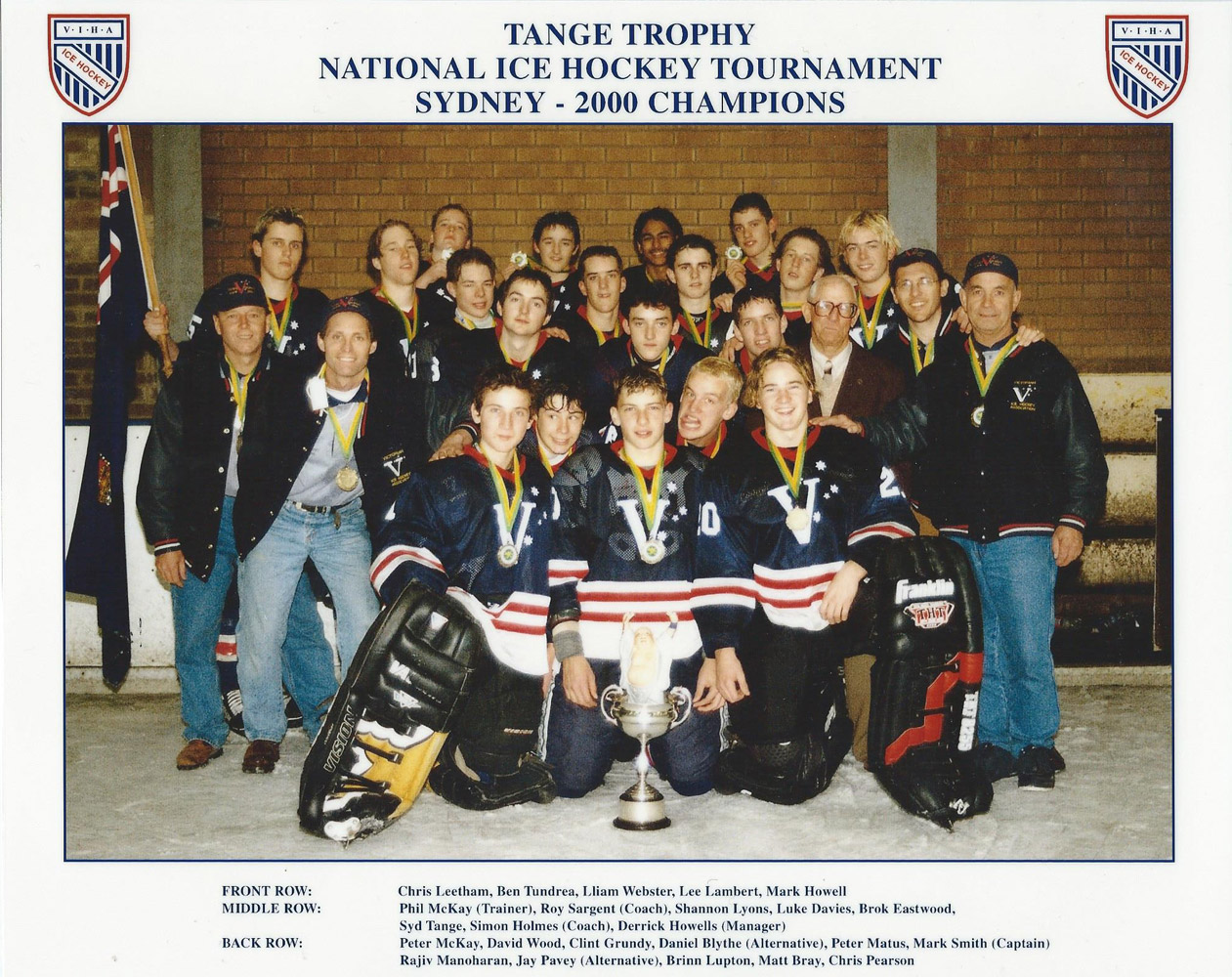

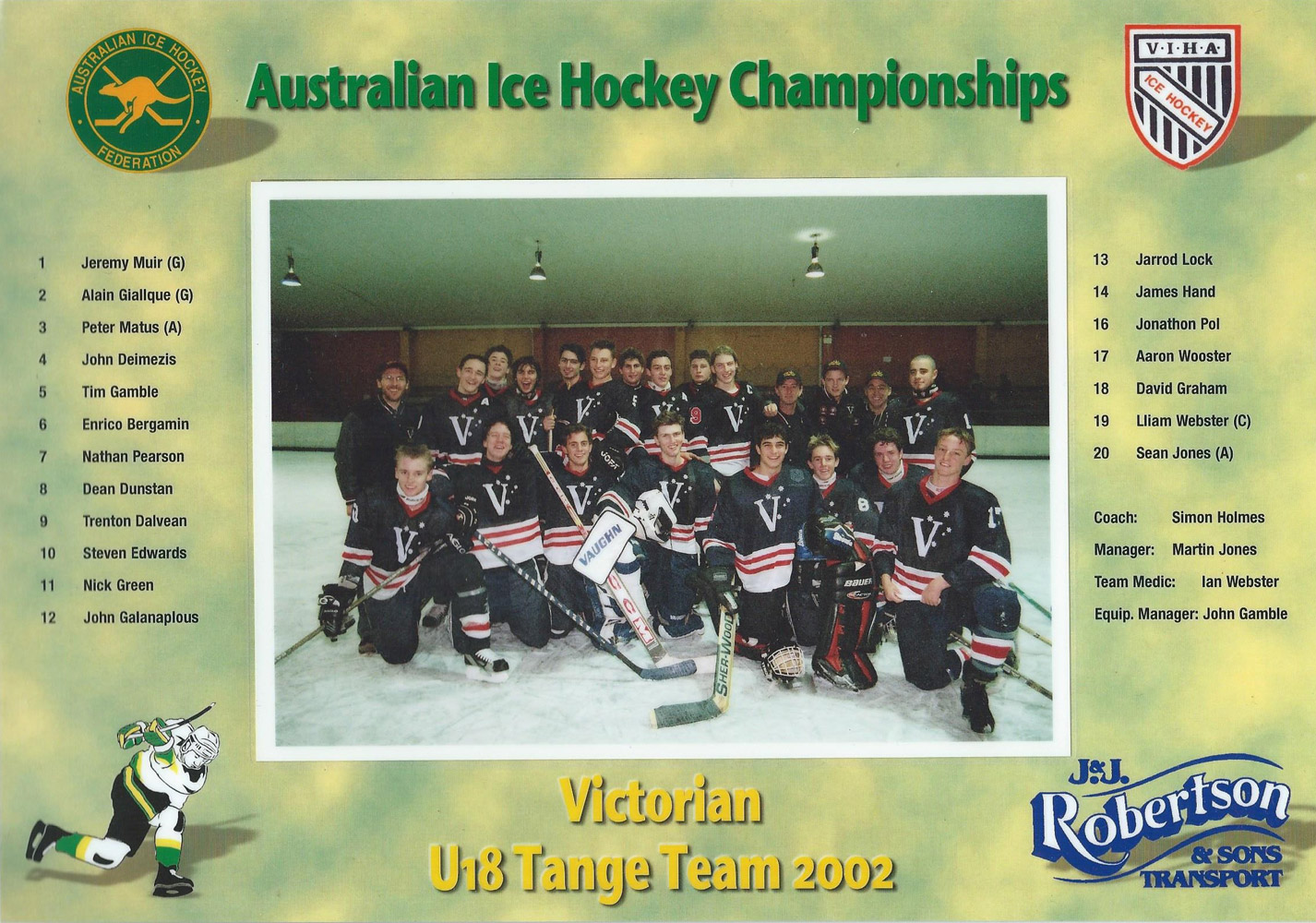

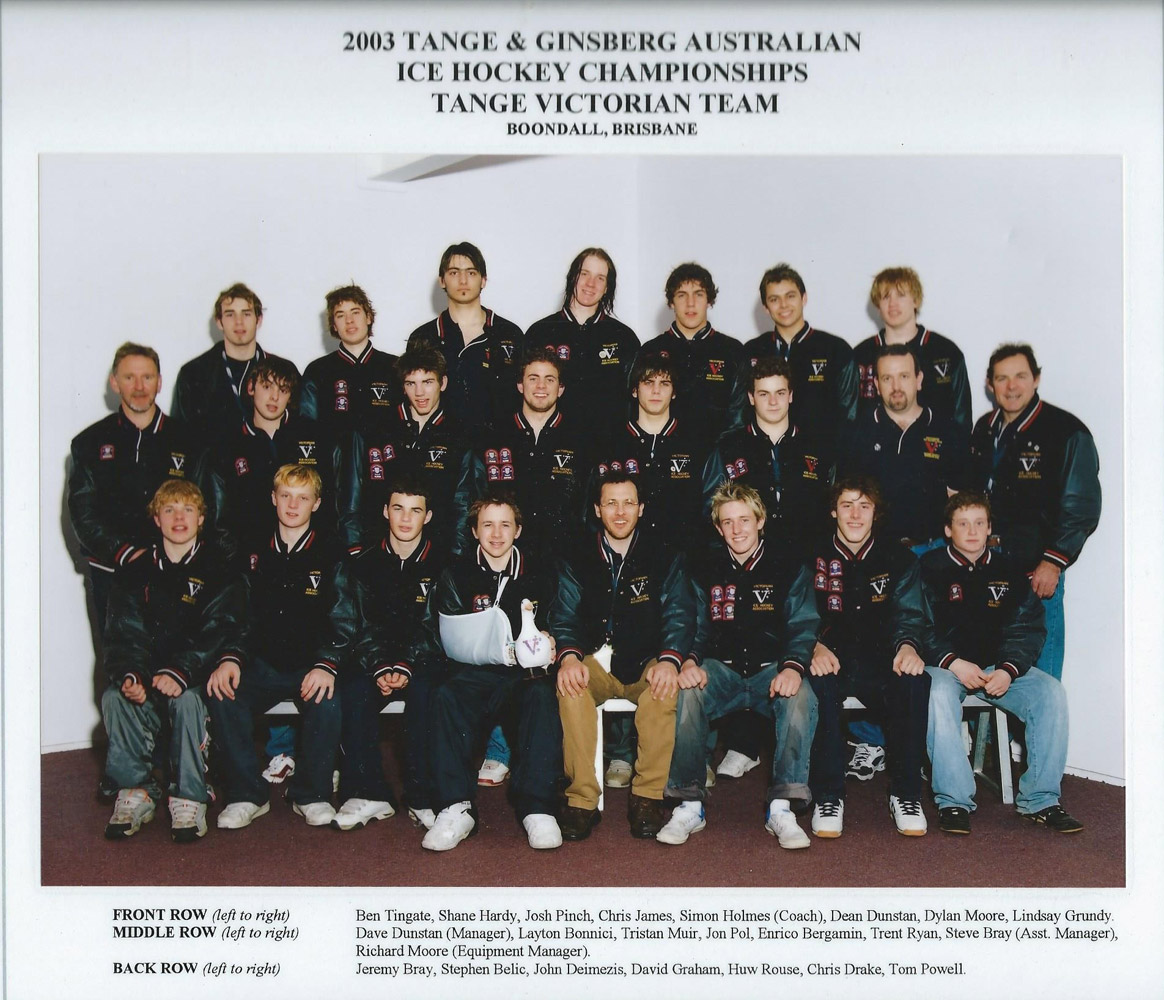

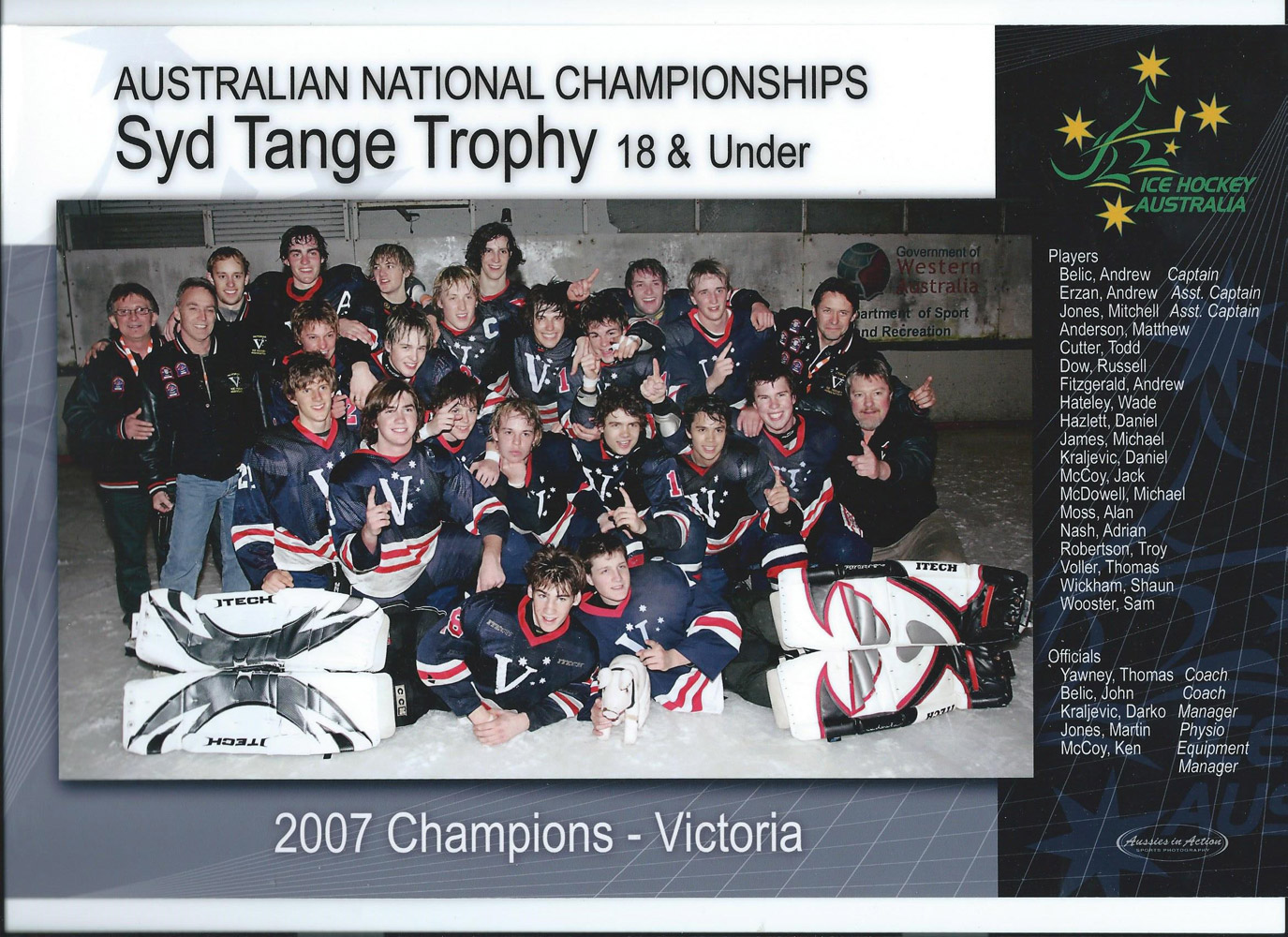

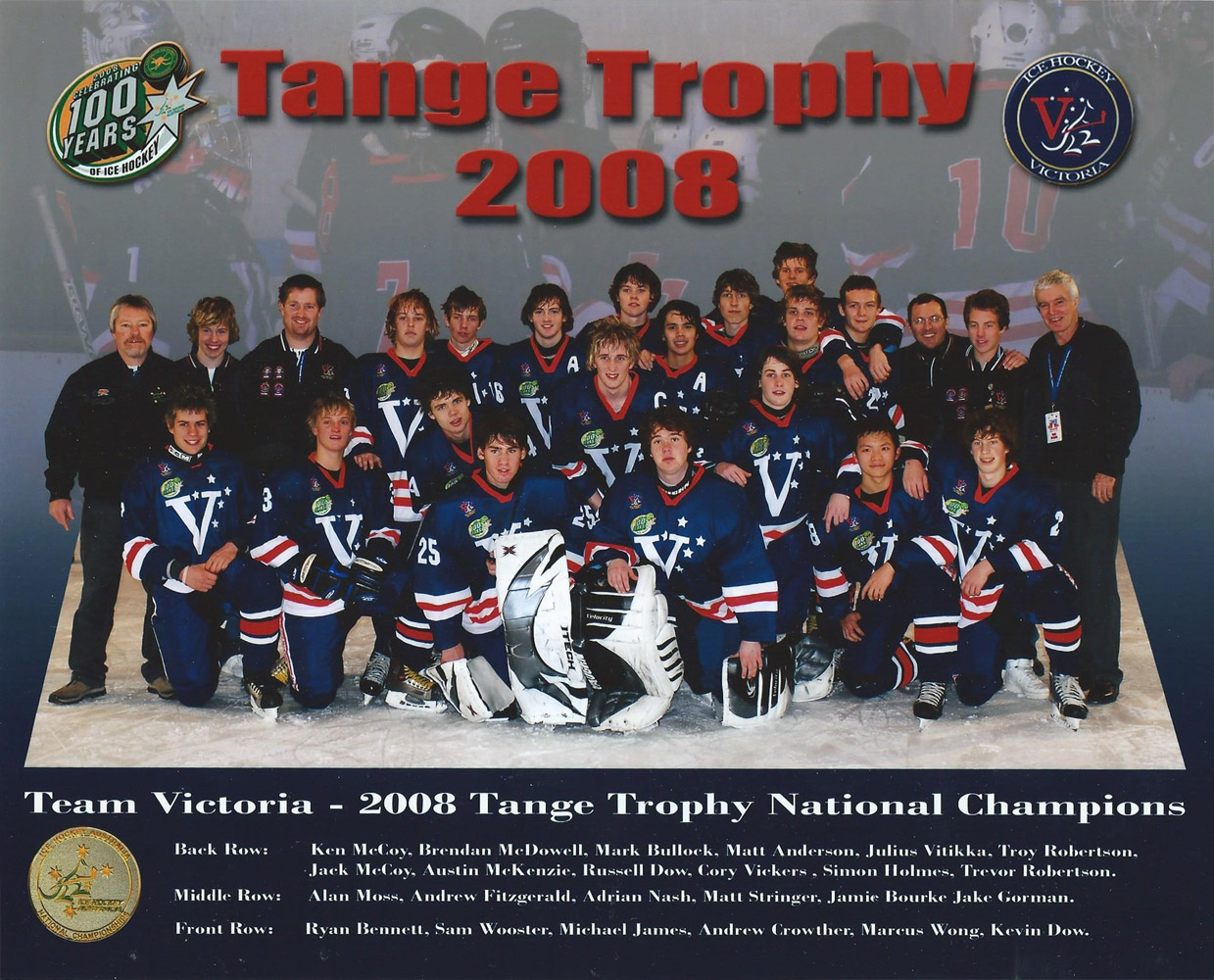

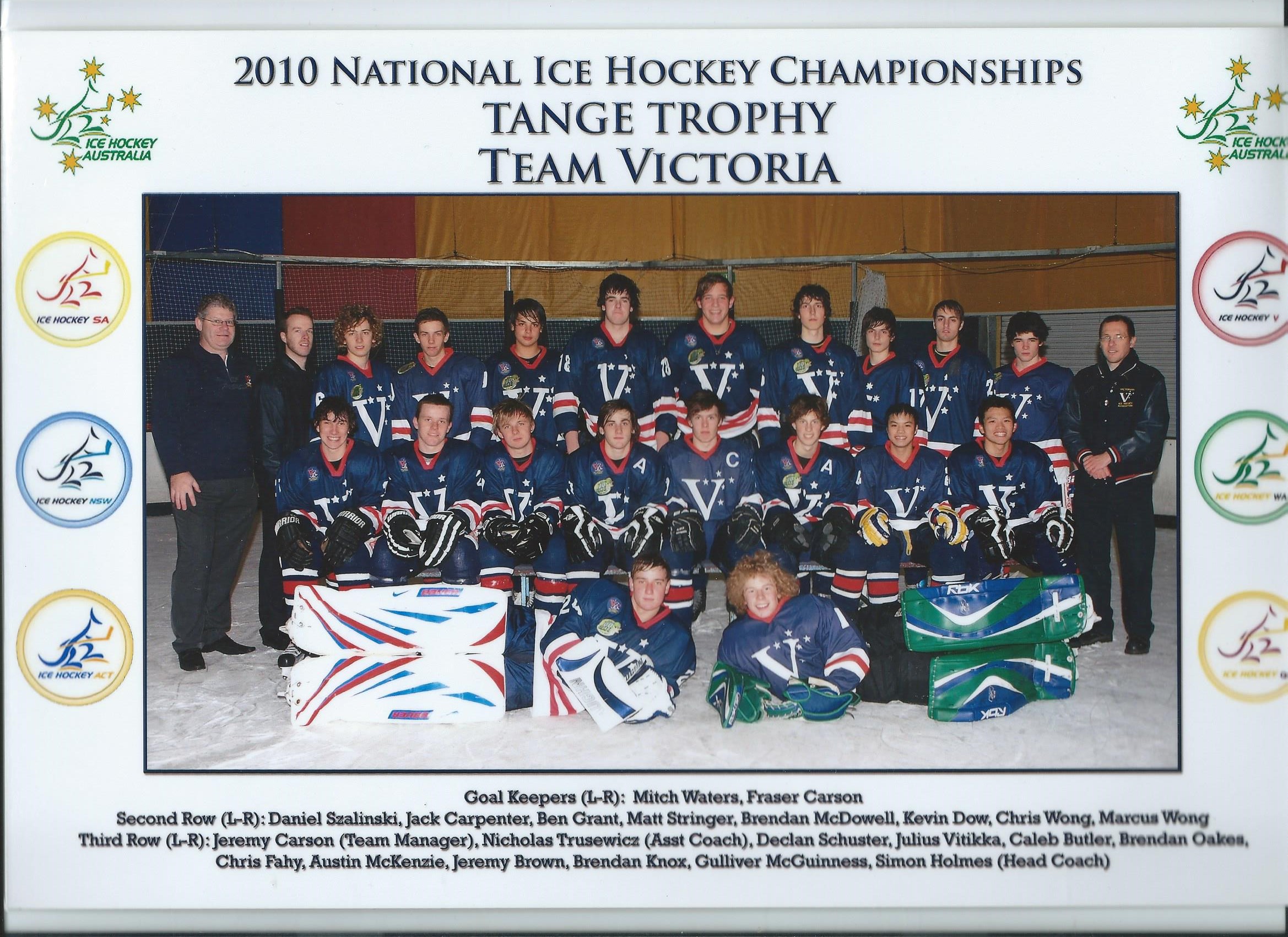

State Tange Trophy team photos (1969 to present). The first true junior National was introduced in 1969 for players under 16-years (later under-18) \ 30 images

A hotel someplace

Part 1: Syd Tange and the game anyone can play

![]() Players who break their line of development at home very often lose their national characteristics as they become hybrids—players with very few qualities that set them apart. Players who develop in their own environment until 21 to 23 (domestic league, national team experience) become better NHL players.

Players who break their line of development at home very often lose their national characteristics as they become hybrids—players with very few qualities that set them apart. Players who develop in their own environment until 21 to 23 (domestic league, national team experience) become better NHL players.

— - World Hockey Summit, Toronto, 2010. [1]

Bruce Charman coaching and St Moritz Juniors, St Moritz Ice Palais, Melbourne, 1960s. Courtesy Jason Sangwin and Bruce Charman.

Bruce Charman coaching and St Moritz Juniors, St Moritz Ice Palais, Melbourne, 1960s. Courtesy Jason Sangwin and Bruce Charman.

THE SOUNDS OF THE CITY completely invaded the air of the half-opened room, waking the young men after having slept the sleep of the defeated for hours on end, oblivious to the pile of drying clothing, decaying travel bags and distressed hockey sticks rising like a deconstructivist set piece at its centre. Otherwise, it was a room like any other, in a hotel someplace or a private home, in Tallinn perhaps, or Helsinki, Zagreb or Katowice, a room not far from the ice arena to where the young Australians must return and fight, to avoid the haunting eyes of their conquerers, their coaches, the overly polite faces of their hosts, the humiliation of relegation to a lower division, a lower world ranking, a lesser world than the one they had left just ten days earlier.

The very first hockey game with a puck in Australia was played in Melbourne in 1907 by a team of schoolboys [13] against a team assembled from the ranks of the touring Canadian Junior Lacrosse Team. The visit produced Australia's first international match in lacrosse before a crowd of thirty thousand at the MCG, and launched the modern form of Australian junior ice hockey.

Yet twenty years and a world war went by before ice hockey received a true age-delimited, junior structure. And it took much longer than that and another world war to reinstate it after it lapsed. Longer still for it to reach the international stage. Ironically, it may not have happened at all had it not been for the wars.

The Roaring Twenties exploded on the ice in a shower of Veuve Clicquot and world freedom, but before the sport could finally resume after the bloodiest of interruptions, someone had to rebuild it. Jack Goodall took it over when he was 27. Many foundation players had been lost to the war, some never to return, others to raising families of their own. Goodall set both the men's and women's games back on their feet, then retired from the association. The sport enjoyed unprecedented growth during the Twenties.

Goodall was a stockbroker. In the wake of the Wall Street crash, when unemployment in Australia doubled to twenty-one percent by mid 1930, he returned to the state presidency after the death of Peter Ross Sutherland. In the depths of the Great Depression, he re-organised the state's clubs with the aim of giving "young players a better chance to improve themselves".

The next season he dropped the St Kilda club and restructured the three others—Hawthorn, Brighton and Essendon—with both senior and junior teams. Seniors played Monday nights, juniors on Thursdays. [5] Inter-club juniors and an inter-schools competition were both created that year, the first true, age-delimited junior ice hockey leagues in Australia.

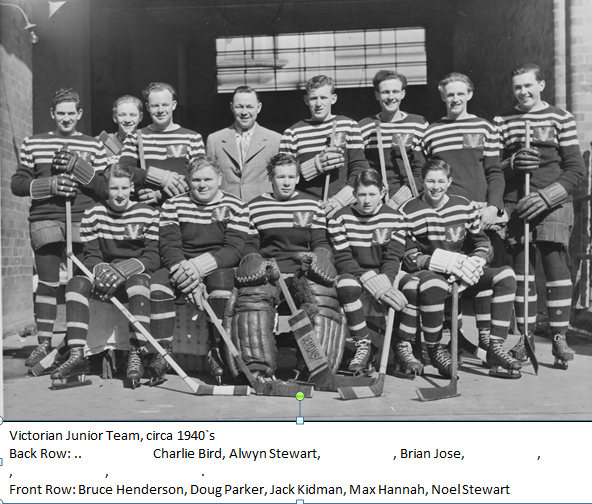

Melbourne Grammar, Goodall's alma mater, won the inaugural Junior Public Schools under-16 competition over Scotch and Wesley College. They played at the Glaciarium on Saturday mornings. [4] Schoolboys had competed in "teams races" in Victoria for some time, and Goodall also redefined the state speed skating championships in 1931, enabling boys and girls to compete in under-sixteen and under-eighteen junior age divisions. [3]

The next big boost to junior hockey came on the eve of yet another world war, when both Sydney and Melbourne received their second rinks and inter-rink matches. Combined with the war interruption, this freed up ice for young players—the junior St Moritz versus Glaciarium teams in Melbourne, and the Ice Palais versus Glaciarium teams in Sydney. [7]

The fledgling junior house league led by Russ Carson in Melbourne "proved highly successful, and the standard of hockey was remarkable for first year players". But rink infighting brought it all to an abrupt halt, and only the practice sessions continued with the junior Topliners and Flyers after the association went into recess. [8] The Rhodes Motor Company and Foy + Gibson sponsored the teams, much like a junior commercial league.

The rink management in Sydney permitted a coaching class every Sunday morning from 6 to 8 for players 16-years and under. They were coached by Fred James, Jim McLauchlain, and later state secretary Syd Tange. Saturday classes continued until the Glaciarium closed in 1955.

Melbourne was similar, especially after the 1941 season when competition hockey was finally suspended. The practice sessions at both rinks over the remaining four years of the war introduced a new wave of skilled teenagers to the decimated game when it resumed in 1946. Players such as Rus Jones and Dave Cunningham in Melbourne. The teenage Geoff Thorne in Sydney.

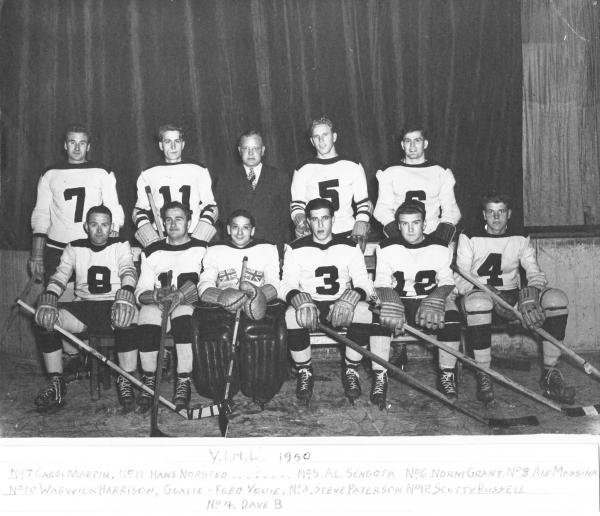

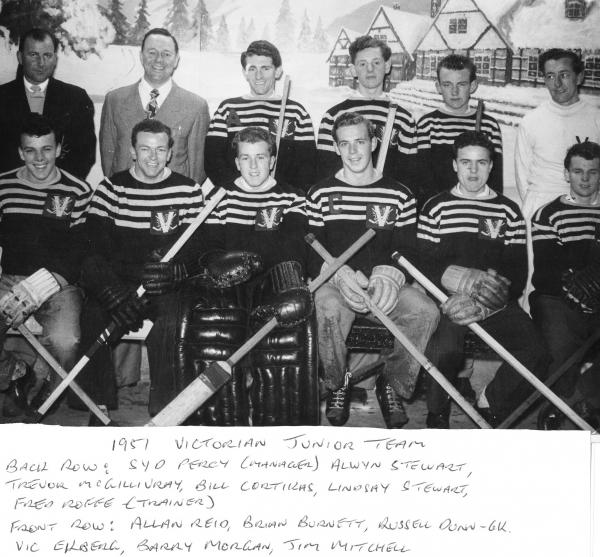

In 1950, Tange and Alwyn Stuart discussed the prospect of a Junior Interstate Competition during a Goodall Cup series in Melbourne. Stuart managed the St Moritz rink and the Pirates club. The idea won support and the two states faced off during the Goodall Cup series at St Moritz on July 27th 1951. Stamina Apparel Co donated the Stamina Trophy for the competition which ended in a 2-2 draw.

Melbourne continued on with its junior program guided by hard-hitting defenseman, Ken Pawsey, who later became a member of the first Australian Olympic Team. Then, incredibly, all hockey in Sydney lapsed when the Glaciarium closed in 1955, until intense lobbying of a local Council resulted in the Prince Alfred Park open-air ice rink opening mid winter 1959. English expat John Caruana managed it for the lessee, Molony and Gordon, of the St Moritz rink in Melbourne.

To help with the rebuild, Caruana offered the association free ice slots to coach juniors between 8 and 9:30 Saturday mornings on the proviso that Syd Tange supervised. The juniors also skated free of charge in the public sessions that followed. The eligible age limit was still 16-years and under, and experienced players formed a coaching panel with the emphasis on basic skating skills. Puck-handling and shooting followed as sticks became available, then scrimmages as skills improved.

The new wave of youngsters wore figure skates and no protective gear but, pleased with progress, Caruana donated pennants for a one-round competition at the end of the season. The coaching panel selected the teams, the boys selected their captains, and the winning captain wrote a letter of thanks to Caruana for his support.

The junior coaching class continued for the term of the St Moritz lease, with most students joining clubs and gaining interstate honours. Caruana's approach at PA extended over the boards and out of the rink, to the young people of the district who were experiencing domestic problems. There was always a meal at PA and use of the rink facilities until their situation improved. But twenty years on from Goodall's defunct junior league, the sport still had no junior competition.

In 1960, more rinks opened in New South Wales: Newcastle, Bondi Junction and Homebush in Sydney. [15] All closed after just a few years, but five more followed at Burwood, Ryde, Auburn, Canterbury and Narrabeen. Half the state's ten new rinks closed over the decade from 1957, but like the war years they had provided precious practice ice for youngsters. The rink at Homebush cradled the state's first organised junior hockey, although it had nothing to do with the state association.

After the return engagement of Ice Capades in Sydney in 1966, Pat Burley moved its tank to an empty factory in the Melbourne suburb of Moorabbin where, in the wave of a wand, it became a public skating rink. The Victorian juniors (Pee Wees) of the era trained under Bruce Charman, with help from Ken Pawsey, Bob Blackburn and the Junior Committee.

Two teams at St Moritz St Kilda played an 18-round inter-rink competition against two from Moorabbin Iceland. They were "exciting, and interesting to all who saw them," wrote Kurt Defris, who considered young players to be "one of the most important sections of our ice hockey". By 1970, ice hockey Olympian Dave Cunningham had joined Charman, Pawsey and Blackburn.

The Homebush Juniors affiliated with the state association in 1967. Canadian Lou Magnuson coached the club led by president R Felton, W Franks (vice-president and secretary) and Bob Watson (treasurer). The coach was excellent with a Junior-B rating, and the Club enjoyed the full support of rink manager, Bob Watson, a former professional instructor at the old Glaciarium.

They played the Brisbane Juniors at home that year, winning two games and tying the other. In October, they played the Warana Junior Ice Hockey Series in Brisbane winning all three games, and again won all their later games against the Wollongong Raiders and a team of juniors in Newcastle.

In 1968, the St Moritz Cats defeated the Rangers to win the St Moritz Junior Hockey Cup. Then, in a reversal of form, the Rangers defeated the Cats in "a very fiery and interesting match" to win the Iceland Cup.

Despite this, an attempt to run a junior carnival in Melbourne did not happen "due to circumstances outside the control of the Victorian body, and lack of interest from other states". But some of the boys from both rinks made the cut for a Victorian junior team. They practiced, and each player received a badge.

Then in 1969, the national association finally introduced a national series for the Under-16 age band. Canterbury hosted the first series, and Prince Alfred Park the second. Victoria won both, and the state's John Horsnell won 'Best and Fairest'.

Ken Kennedy, Jim Mortimor and Mark Murphy presented the trophy, which they wanted to name after Syd Tange, whose interest in the juniors had then spanned twenty years. Australia's first junior ice hockey national, the Tange Trophy, continues to this day as the Under-18 Men's National.

Against a grey backdrop of senior self-interest, interstate parochialism, and a general malaise of indifference, Goodall's age-delimited junior hockey initiative was finally raised to the national stage. But it took 39 years, and it may not have happened at all, if not for free ice and a world at war.

THE HISTORY OF JUNIOR ICE HOCKEY in Australia is at best limited, and at worst deplorable. The good years are highly correlated with an increase in the supply of new ice, or the freeing up of existing ice. For instance, with the opening of new rinks, or during both wars, or when rink operators made their ice available free of charge for junior practice sessions.

The boom years in the Twenties and Fifties were in large part a product of the interruption to competition hockey. Youngsters could develop in ways that were rarely achieved in peacetime. During the Second World War in Victoria, juniors developed with commercial sponsors and no controlling authorities. In the Eighties, the boom was largely a product of the new national player development system formalised by Elgin Luke and others, despite the occasional all-time shortage of ice. Yet even that is not the whole story.

An amateur sport is not a federal government, nor a large corporation like North America's NHL. But the sport of ice hockey in Australia is a part of a worldwide governing body with 76 member nations who ostensibly follow its rules, receive millions of dollars in annual fees from players, and IIHF funding to help many of its best to compete internationally. It might be non-profit, but it is still big business, and the IIHF expect the sport's administrators to accept their common duties to run in an organised way for the good order of the sport, and to give aid to develop young players, coaches and game officials.

No-one would ever have a high-rise tower designed and built by a real estate agent with no architectural training or construction experience. No-one would ever have major surgery performed by a GP without a surgery degree who had never set foot inside an operating room. Yet the management qualifications and experience of most political appointees in the sport of ice hockey in Australia, let alone their technical qualifications, are no more relevant to their positions than this pair of hypothetical candidates.

The hockey family entrusts administration of a sport enjoyed by many thousands of people to a cast of well-meaning political loyalists with little or no management experience. They may be smart, committed, and sometimes high-energy workaholics, but most have never run anything except, perhaps, a political campaign to gain power.

We are a society obsessed with credentials. We demand board certifications for our professionals and licenses for just about everything, from plumbers to day-care providers. In addition to formal training and degrees, we also expect demonstrated experience and the testimonials of satisfied clients and customers.

Yet, when it comes to selecting the top leadership of the executive boards of our sporting clubs and controlling authorities, those responsible for the health and safety of players and officials, we abandon essentially all professional standards. We accept the rather mindless notion that any bright and public-spirited citizen can run the sport.

We turn a blind eye when they don't stand down from voting on matters in which they have a conflict of interest, material or perceived. We accept unethical and even illegal practices until someone is proven guilty, resigning ourselves to a long history of no apparent intervention by a higher authority. And, in particular, from those who have the required clout in their purse-strings.

Twenty years ago, when someone asked the IIHF what their reaction would be to the NHL or its member teams or owners setting up and financing a first class pro hockey league in Europe, their reply was rather hostile. "That is exactly what the IIHF and European hockey federations fear," said the IIHF representative. "The NHL or their teams or owners would come in with their big money and ruin the sport".

How would that ruin the sport?

"The money would be used to buy the best players," they said. "[It] would not filter down to support the junior player structure, the moneys would not remain invested in European hockey in general, but would be taken out for quick profit, etc". [19]

If that sounds familiar it is because amateurish attempts to "professionalize" the sport in Australia have played out that way right up to the present day. The main problem with the Australian game is not the shortage of ice or participants or fans. It is the comparative handful of self-interested people who, in their attempts to hold power, treat sports administration as a game anyone can play.

Part 2: Juniors in search of excellence...

[1] World Hockey Summit, Junior Development Around the World, Slavomir Lener, Toronto, 2010.

[2] Sporting Globe, Melbourne, 4 Aug 1928, p 6.

[3] "Ice Hockey: The NSW Ice Hockey, Association Inc. Australia - Facts and Events 1907-1999" by Syd Tange, 1999. Extracts published in 2007 on the IHNSW web site for the 2008 Centenary.

[4] The Age 20 June 1932, p 4. "Melbourne Grammar Defeat Scotch College". Also see The Argus, Melbourne, Mon 27 Jun 1932, p8 and The Argus, Melbourne, Mon 11 Jul 1932, p4.

[5] Advocate, Melbourne, 21 May 1931, p 31. "The Glaciarium".

[6] The Age, Melbourne, 13 Aug 1907, p 4. "Hockey at the Glaciarium".

[7] The Age, Melbourne, 4 September 1939, p 4, "Junior Players Show Promise", and 25 September 1939, p 6, "Junior Match".

[8] The Age, Melbourne, 23 July 1940, p 4, "Junior Ice Hockey".

[9] The Argus, 3 February 1951, Ken Moses Column

[10] Table Talk, Melbourne, 4 June 1931 p 36.

[11] The Sydney Morning Herald, 29 September 1938, p 16.

[12] The Sydney Morning Herald, 11 Aug 1938 p 16.

[13] Tange, 1999, Ibid. New South Wales Ice Hockey Association, Minutes of Meeting, March 21st, 1923.

[14] Australian Ice Hockey Carnival program, NSW Ice Hockey and Sports Club Ltd, 1965, p 11.

[15] Ice Hockey Week, Official Programme, NSW Ice Hockey Association, May 1961.

[16] A tournament for the 11 and under age band named after John McRae Williamson was conducted between 2003 and 2010, but it became a Jamboree and is no longer a competition.

[17] The Christian Science Monitor, Sydney, 17 May 1982. "Alien sport of ice hockey gains Australian beachhead", by Chris Pritchard.

[18] Image courtesy of Basil Hansen, Ice Hockey Victoria.

[19] International Sports Law and Business, Vol 2, Aaron N Wise, Kluwer Law International, 1999.