Legends

home

[ HOCKEY ] S for Sugar

Hugh 'Spot' Lloyd (1912 - 1943)

![]() Few subjects in Canadian sport arouse as much passion as debating the origins of ice hockey, Canada’s mythical national pastime. Hockey fans, hobbyists, and even a few sports scholars have been known to "mix it up" off the ice when the discussion inevitably returns to the hotly contested matter of Creationism versus Evolution. Ten years ago at the 2001 "Putting It on Ice" Conference, E. Gay Harley, likened the search for the "birthplace of hockey" to the dubious claim of Baseball’s Cooperstown, New York, and made a compelling case for the "evolutionary model," arguing that hockey evolved, from first Amerindian-European contact onward, and that different aspects of the game developed over time in various places.

Few subjects in Canadian sport arouse as much passion as debating the origins of ice hockey, Canada’s mythical national pastime. Hockey fans, hobbyists, and even a few sports scholars have been known to "mix it up" off the ice when the discussion inevitably returns to the hotly contested matter of Creationism versus Evolution. Ten years ago at the 2001 "Putting It on Ice" Conference, E. Gay Harley, likened the search for the "birthplace of hockey" to the dubious claim of Baseball’s Cooperstown, New York, and made a compelling case for the "evolutionary model," arguing that hockey evolved, from first Amerindian-European contact onward, and that different aspects of the game developed over time in various places.

— Paul W Bennett, Schoolhouse Institute, Halifax, NS, and Saint Mary’s University, 2012. [25]

HE SPEAKER IN THE DINING ROOM of Winnipeg's St Regis Hotel was explaining how the nickname "Babe" had stuck. It was a gift, he said, from friends who jokingly likened him to Babe Ruth when they saw him play baseball as a small boy. "But I always dreamt of playing NHL", he confessed to a round of applause, and not one soul there looked the least bit surprised. He had turned down an invitation to the Olympics to turn pro yet, just the year before, this particular Manitoba son was the MJHL Scoring Champion with Kenora Thistles. Now he was a New York Ranger and, in less than a decade, Babe Pratt went on to become a Stanley Cup champion, not once, but twice; first, with the 1940 Rangers, then the 1945 Leafs, winning the Hart Memorial Trophy along the way, and Hockey Hall of Fame immortality.

HE SPEAKER IN THE DINING ROOM of Winnipeg's St Regis Hotel was explaining how the nickname "Babe" had stuck. It was a gift, he said, from friends who jokingly likened him to Babe Ruth when they saw him play baseball as a small boy. "But I always dreamt of playing NHL", he confessed to a round of applause, and not one soul there looked the least bit surprised. He had turned down an invitation to the Olympics to turn pro yet, just the year before, this particular Manitoba son was the MJHL Scoring Champion with Kenora Thistles. Now he was a New York Ranger and, in less than a decade, Babe Pratt went on to become a Stanley Cup champion, not once, but twice; first, with the 1940 Rangers, then the 1945 Leafs, winning the Hart Memorial Trophy along the way, and Hockey Hall of Fame immortality.

Through the 1930s and '40s the St Regis on Smith Street had been a popular place for luncheons and banquets for social service clubs, sports leagues and business associations. From the 78th Battalion Association to the Good Roads Association, it was more than likely they held their annual dinners there for many years. [11] On this particular night in April 1936, the members of the Hydro Brigden Hockey League were winding up a successful season with a dinner and entertainment. Stan Evans (Fort William Forts) was a guest of honour, a decade before the Stan Evans Stylists were runners-up in the 1946-7 Manitoba Senior Hockey League season.

Winnipeg Spring. Food lines, relief work, despair. The gloom of the Great Depression. Thirty percent of Canada's labour force was out of work by 1933, and one-fifth of the population were dependent on government assistance, but it was the prairie provinces that were hardest hit. There, two-thirds of rural folk were on assistance and more people emigrated to other countries than at any other time in North American history. Some went back to their native lands, others went to England, Australia or South Africa.

Like Pratt, the other guest speaker that night was also from the Canadian prairie, another Winnipeg son who had grown-up skating at The Forks, but who now played for Queens Ice Hockey Club of London in its inaugural season in the English League. Enough new rinks had opened over there for a League to be formed five years earlier in 1931 with Oxford University, Grosvenor House Canadians (Westminster), Prince's (London), London Lions (Golders Green), Manchester, Sussex (Hove) and Cambridge University. [12]

Then, the new Prince's Ice Hockey Club had merged into Queens Ice Hockey Club in 1932, having moved from the Westminster rink where it was founded three years prior, to Queens Ice Club when it opened on October 3rd 1930. [9] Located in Bayswater, Queens is now the oldest surviving ice rink in the United Kingdom, the second rink developed by Alfred Octavius Edwards after his rink at the Grosvenor House Hotel, in the space known today as the Great Room. Australia's Jimmy Brown played hockey there for Grosvenor House Canadiens five years earlier.

The diners sat captivated by a tale of three king-size ice arenas that had just opened in London at Wembley, Earls Court and Harringay. Together with three smaller ones in Brighton, Richmond and Streatham, the Brits had created a league that was virtually professional in season 1935-36 because the clubs were able to pay higher wages than Depression-hit North America. [12] Now known as the British sport's Golden Era, the arena teams attracted crowds of up to 10,000 during the years before World War Two, even in a time of meagre public entertainment. The English clubs brought over top-class players from Canada, some even returning home to play NHL.

Hughie Lloyd knew because he was among the very first wave, and he didn't just play for Queens. He had repped for Great Britain against Europe and Canada [13] by the time he had decided to move to Australia. Britain had won the triple crown of world hockey in 1936, dispelling any lingering doubt they had come of age as an international hockey power. The first ever TV broadcast of hockey of any kind took place in Britain the next year, and a match was broadcast live there for the first time the following year. [24] The Canadians had successfully exported their game to Britain, and the British were commercializing it. But, unlike Australia, they were generally intransigent on matters of international governance, and this frustrated Canadian efforts to control their national game.

Born in Winnipeg on May 23rd 1912, Hugh Herbert Henry Lloyd was the son of Thomas and Julia Lloyd of 768 Home Street in Winnipeg. He had a sister, Mrs H L McCann, who lived at 968 Dominion St, and four brothers: Joe in England; Tom at 717 Ingersoll St; Frank in Dominion St; and Fred at 1076 Downing St. [20, 27] Lloyd attended Wellington, Sparling and Daniel Mclntyre schools, St Jude's church and the parish Boy Scouts. He worked for the design firm, Rapid Grip and Batten Ltd, before leaving for England in 1935. [27]

In Melbourne, he was a process engraver [13] and played the tail-end of the 1937 hockey season at Melbourne Glaciarium. "A fast, tricky left-handed forward" [1] said the Sydney sporting rag, Referee, in the lead-up to State team selection — "regarded by many Victorians as the leading ice hockey player in Australia". [4] "The British Ice Hockey Association is being granted official powers over professional as well as amateur administration," they trumpeted, "there is a chance of professional ice hockey coming to Australia too within the next few years. Nothing concrete is available for release yet, but rumours have been circulating for some time, and they are anything but idle rumours". [18]

Imported players were virtually unheard of until Jimmy Bendrodt opened Sydney's second rink, the Ice Palais, in the Hall of Industries at Moore Park that year. But already the sport was compound fracturing under the pressure to commercialize, to professionalize. Now Victoria had issued an ultimatum to the NSW Ice Hockey Association — withdraw the Canadians George Balork and Ken Tory from the State side, or the game was off. With Gilbertian dramatics, New South Wales slammed the rule book on the table, challenging Victoria to find one that prohibited the playing of Canadians, and flatly refusing to "allow another state to dictate the personnel of her team".

After the chest beating came compromise, one a side, and so Lloyd represented Victoria in his first Goodall Cup in 1938. His opponents played the Canadian Bears', Balork, but they already had Percy Wendt, a Canadian ex-pat playing his eighth consecutive Goodall Cup series. Wendt became the top goal-scorer of the first half century of Goodall Cup hockey.

The Vics were coached by Fred Palmer during his first term as Trade Commissioner in Melbourne for the Canadian Government. Turner had held that role in nine countries since 1922 and he was widely experienced in coaching ice hockey. [13] Battling to break a sixteen-year Cup drought, Victoria drew the first match in which Lloyd's "judgement and position play made him a continual menace to New South Wales". [5] It was a physical game with as many as "half a dozen spread-eagled at a time and several penalised for doubtful tactics". [5]

In the second test, Lloyd and the Vics lost 2-0, reportedly their "failure to handle the puck in front of the goal costing them the match". But it was also true that Canadian expat, Percy Wendt, had starred, scoring both goals. As could be expected, both Canadians were among the four best players. New South Wales won the decider 2-1, although "there was little difference between the teams, the winner showing a little more teamwork and spirit ... New South Wales officials expressed the opinion that the standard of Victoria's play had never been higher, and predicted that the cup would soon change hands". [17] It was little more than a back-handed compliment and the bitter acrimony hung like cordite in the air throughout the war years.

In October 1938, four Victorian players were invited to represent Australia against the Canadian Bears in Sydney and Lloyd was among them. The invitation from Bendrodt's breakaway Australian Amateur Ice Hockey Association (AAIA) placed LLoyd, Ellis Kelly, Johnny Whyte and Colin Mitchell, in a delicate situation because, although determined to play, the State controlling authority had just decided to suspend anyone who did. The AAIA was the first real threat to the Australian Ice Hockey Federation and, in the end, all four flew to Sydney and "Lloyd was superb". He shut down the Canadian, Fielder, the local press concluding he was "probably the best defensive player seen on a Sydney rink for many years". [7]

In 1939, Lloyd was captain of the newly-formed Glaciarium Rangers IHC [3] and vice-captain of the Victorian Goodall Cup team with fellow Canadian ex-pats, Russ Carson and George Balork of the Canadian Bears, both of whom had moved to Melbourne from Sydney. Victoria tied the first two games, each two apiece, but lost the second 2-1 leaving the local press to rue, "It was hard luck for the Victorians that Hughie Lloyd, their captain, could not make the trip to Sydney on the day of the test". His replacement defender, Johnny Whyte, was prevented from flying to Sydney by poor weather conditions". [22] Russ Carson was in excellent form, but unsuccessfully disputed the second New South Wales goal. Yet again Victoria was poised for victory after seventeen years in the wilderness, but there was to be no further interstate hockey until after the war interruption in 1946.

Local hockey continued in Melbourne in 1940 and 1941 with a fourth team, Russ Carson's Rhodes Topliners, joining the Bombers, Rangers and Flyers. Lloyd continued to play. He married Bette Eileen McEvoy in September 1941 [20, 27] and they lived in a little Edwardian cottage at 69 Milton Street in Elwood, about one kilometer from the newly-opened St Moritz Ice Skating Rink. Bette was a Prahran girl born in 1919, the daughter of John McEvoy and Aileen Florence Graves. [20]

On the last day of February 1941, Lloyd had enlisted in the Royal Australian Air Force. His father and brother Tom had served in the Great War [27] and, so far that year, the British and Australians had captured Bardia in Libya, Tobruk, Benghazi and Mogadishu. US policy at that time had slowly began to shift from neutrality to providing aid to the nations at war with Germany, Italy and Japan. Lloyd served as a Sergeant with 467 Squadron based at RAF Bottesford in England. Equipped with the now famous Avro Lancaster heavy bombers forming part of 5 Group RAF Bomber Command, they were part of the strategic bombing offensive against Germany.

Notionally an Australian squadron under the command of the Royal Air Force, it consisted of personnel from a mix of Commonwealth nations. It flew its first operation on January 2nd 1943, laying mines off the French coast near Furze and, five days later, it completed a night bombing raid on Essen in Germany. Sergeant Lloyd's squadron then moved to RAF Winthorpe and the No 1661 Heavy Conversion Unit, where 5 Group's Operational Training Unit squadrons were converted to flying the new Manchesters and Lancasters.

The Lancaster returning from another twenty-minute night circuit practice descended into the glare of runway floodlight at RAF Winthorpe. It was ten-twenty on the night of February 1st 1943 when Sgt B F Wilmot, the Australian pilot of L 7530, pulled out of the descent and decided to go around again. On the second attempt, he carried out the correct procedure, applying full throttle with the undercarriage up. But he was dazzled by the floodlights and could not see his instruments. The huge bomber over-shot the runway and flew into rising ground at Main Road, Beacon Hills in Newark-upon-Trent. It struck the side of a hill and crashed, injuring all crew and killing the gunner in the tail turret, Sergeant Hughie Lloyd.

Today, RAF Winthorpe looks like the green fields of a Blake poem and, except for a memorial museum, it is as far removed from the thundering calamity of its wartime operations, as the living imagination allows. The cemetery at Newark-upon-Trent in Nottinghamshire is just as green between the grid of white headstones, which is laid out with the same military order and precision as a parade ground of soldiers at attention. Lloyd was just thirty when he came to rest there. [23] His father, Thomas, died back home in Winnipeg a few months later on April 9th 1943. His mother, Julia, lived on until 1959 and both are interred at Brookside Cemetery in Winnipeg. [19] Sgt Hugh Lloyd is commemorated on Page 182 of the Second World War Book of Remembrance of Veteran Affairs Canada, the Canadian Virtual War Memorial and the Australian War Memorial.

In Melbourne, Lloyd is best remembered for the last five seasons of ice hockey he played there from the age of twenty-five. In fact, there are those who like to credit him with showing the Victorians how to play the blue-line game, even though they had been playing competitively for three decades. Such is the importance to Canadians of their place at the head of International hockey, even back then during the first three decades of European expansion from 1908. Lloyd swept across Victorian hockey like a blizzard across his hometown prairie and, like expat Canadian coaches Bud McEachern and Frank Chase to follow, he was an important trail blazer here, who had experienced both the amateur and the professional games.

On three continents Lloyd had lived hockey, and at a crossroads in the evolution of the international game, when Britain followed America, and a divided Australia seemingly followed Canada. He was a necessary acquisition for a State team struggling for competitive balance against opponents who had already played a crack Canadian goal-scorer for seven seasons, and ruthlessly corralled a national trophy for sixteen. Although Lloyd left us clues, we cannot ever know what might have happened had war not intervened — had he defended his net, and not the free world.

Or can we?

![]()

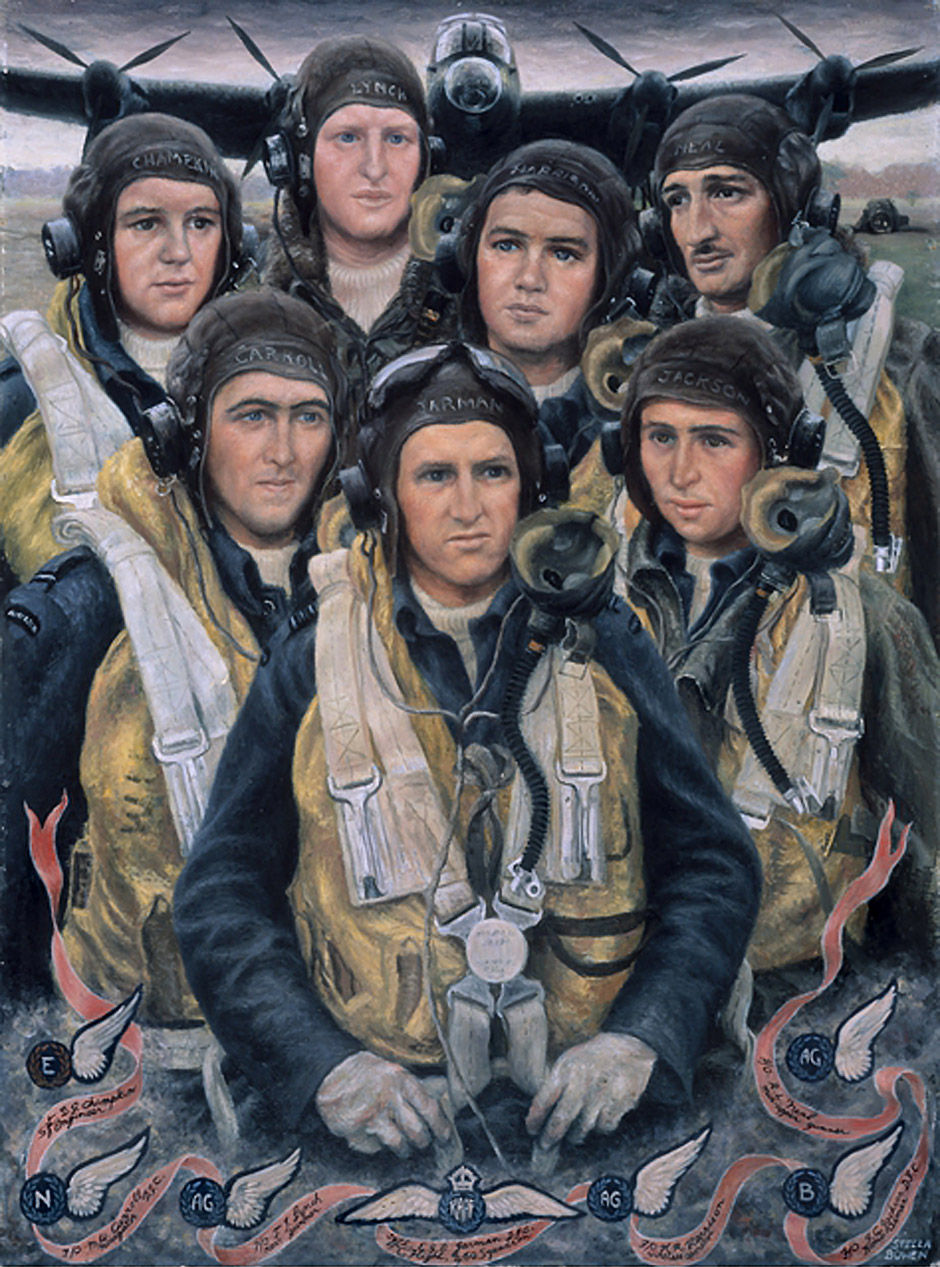

Image [slideshow above]: 460 Squadron Lancaster bomber crew in 1944. All but Flying Officer T J Lynch died during a night raid on Germany. Painting by official war artist Stella Bowen, Australian War Memorial ART26265.

Video (slideshow above, sound clip only): This radio chatter clip is from a Lancaster Bomber which is flying a mission over Germany during World War Two. The bomber is attacked by a German fighter later on in the clip. The crew seems to panic as the fighter engages them, and the captain at one point shouts "Okay, don't shout all at once!" Eventually one of the gunners manages to bring down the German fighter.

Lefty: Percy Frederick Otto Wendt (1912 - 1995), Percy Wendt

Bendrodt's Bears: the first commercialisation of ice hockey, Sydney 1938

L to R: Colin Mitchell, Ellis Kelly, Johhny Whyte and Hugh Lloyd boarding their flight to Sydney to play the Canadian Bears, 1938. [15]

Gunner in the Nash + Thompson FN20 tail turret of a Lancaster, Royal Air Force. Photograph CH 12776, Imperial War Museums.

'S for Sugar' from Lloyd's 467 Squadron, veteran of 118 missions, and now featuring in the RAF Museum.

Lloyd's gravestone at Newark-upon-Trent Cemetery in Nottinghamshire, England.

Citations:

[1] Referee, Sydney, 30 June 1938, p 23.

[2] Referee, Sydney, July 21, p 23.

[3] The Argus, Melbourne, 30 August 1939, p 9.

[4] Referee, Sydney, 15 September 1938, p 23, Victorian Ice Hockey Team.

[5] The Argus, Melbourne, 31 July 1939, p 12. Ice Hockey Draw.

[6] The Argus, Melbourne, 5 October 1938, p 30. Ice Hockey Suspension Threat.

[7] Sporting Globe, Melbourne, 22 Oct 1938, p 4.

[8] The Mercury, Hobart, 24 March 1938, p 7.

[9] Homes of British Ice Hockey, Martin C Harris, Tempus, 2005.

[10] The Winnipeg Tribune, Winnipeg, Sat, April 25, 1936 p 32. Hockey League Winds Up Successful Season.

[11] Winnipeg Downtown Places website by Christian Cassidy, last accessed 20 Sep 2015. Online

[12] Ice Hockey Journalists UK, Ice Hockey History, Stewart Roberts, last accessed 21 Sep 2015. Online

[13] Australian War Memorial, RAAF service records 401508, Hugh Herbert Lloyd.

[14] Referee, Sydney, 28 April 1938, p 19. Canadians for Melbourne.

[15] Sydney Morning Herald, 14 October 1938, p 14. Photograph of Hugh Lloyd boarding a plane to Sydney.

[16] The Argus, Melbourne, 9 August 1938, p 18. NSW Wins Ice Hockey.

[17] The Argus, Melbourne, 11 August 1938, p 17. NSW Retains Cup, Brilliant Ice Hockey.

[18] Referee, Sydney, 5 May 1938, p 18. English Ice Hockey, Professionalism On The Way.

[19] Brookside Cemetery Winnipeg, Deceased Persons Search, Thomas Lloyd died 9 Apr 1943, Julia Lloyd 28 Dec 1959.

[20] Manitoba Vital Statistics Agency, Reg No 1912-011533 Hugh Lloyd Birth on May 23rd 1912 to mother Julia. Lloyd's birthdate in war service records is May 24 1913.

[21] Victoria Births Deaths and Marriages, Marriage Index, 1921-1942.

[22] Referee, Sydney, 10 August 1939, p 23. NSW Retain Goodall Cup.

[23] Australian War Memorial, RAAF Fatalities in 2nd World War, Compilation by Alan Storr, 2006, entry 401508 Sergeant LLOYD, Hugh Herbert, p 218.

[24] "Constructing the Hockey Family, Home, Community, Bureaucracy and Marketplace". Proceedings of the "Putting it on ice" Hockey Conference, 2012, Lori Dithurbide and Colin Howell eds. St Mary's University, Halifax, NS, Canada. Chapter "The Skaters of Sydney and Streatham: Exporting Hockey to the British Empire between the Wars". Daryl Leeworthy, Huddersfield University, p 315.

[25] Proceedings of the "Putting it on ice" Hockey Conference, 2012. Ibid. A Family Squabble: What's Behind the Quest for Genesis in the Canadian Hockey World? Paul W. Bennett, Schoolhouse Institute, Halifax, NS, and Saint Mary’s University, p 20.

[26] Holdworthy, Ibid, p 316.

[27] The Winnipeg Tribune, February 8, 1943, p 11. Believed Dead.