Legends

home

You may write me down in history

With your bitter, twisted lies,

You may trod me in the very dirt

But still, like dust, I'll rise.

- Maya Angelou

The Young Reids

Overview

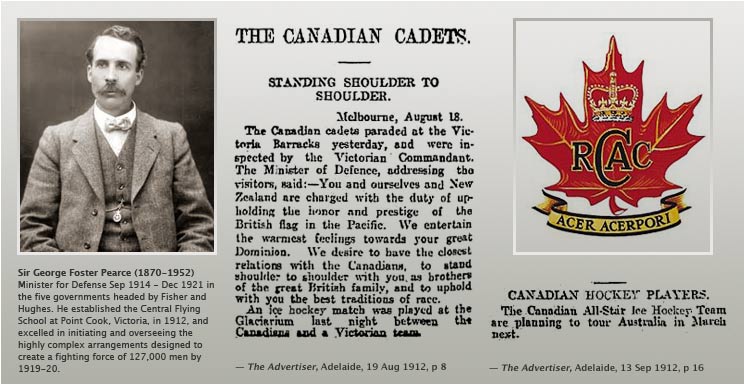

HREE THINGS HAD EMERGED AS CRITICAL to the viability of ice sports in Australia: an International size rink; established links to prospective athletes; and, in the case of hockey, the introduction of Canadian rules and equipment. Henry Newman Reid had presided over all three and the first to consolidate and develop it were Reid's own three sons and daughter. The first decade had brought the commencement of ice sports to Sydney, guided initially by Dunbar Poole and James Thonemann; consolidation of ice sports in Melbourne under the Reids; and the birth of Interstate hockey. In the second, the Reids moved to Sydney; developments in Melbourne leveled-out, when Leo Molloy took over the reins with Cyril MacGillicuddy and Molony and Gordon; and New South Wales achieved an enduring ascendancy, opening its first golden age. The organisers who had revived ice sports after the war, carried them through the latter years of the twenties, yet this was also a decade characterised by empire building in some areas, and a costly lack of Interstate cooperation.

HREE THINGS HAD EMERGED AS CRITICAL to the viability of ice sports in Australia: an International size rink; established links to prospective athletes; and, in the case of hockey, the introduction of Canadian rules and equipment. Henry Newman Reid had presided over all three and the first to consolidate and develop it were Reid's own three sons and daughter. The first decade had brought the commencement of ice sports to Sydney, guided initially by Dunbar Poole and James Thonemann; consolidation of ice sports in Melbourne under the Reids; and the birth of Interstate hockey. In the second, the Reids moved to Sydney; developments in Melbourne leveled-out, when Leo Molloy took over the reins with Cyril MacGillicuddy and Molony and Gordon; and New South Wales achieved an enduring ascendancy, opening its first golden age. The organisers who had revived ice sports after the war, carried them through the latter years of the twenties, yet this was also a decade characterised by empire building in some areas, and a costly lack of Interstate cooperation.

The decade opened after the fire at the Melbourne rink yet, between 1917 and 1920, the net annual profits of the publicly-listed Melbourne Ice Skating & Refrigeration Co, ranged between £2,500 and £3,500. This was equivalent to about 10 percent of the net annual profits returned by the State Savings Bank of Victoria during the same period. The Gower Cup for women's interstate ice hockey competition was introduced in 1922, and the first series was played the following year, when the first National controlling authority for ice hockey in Australia was born, with John Goodall as president. Michigan-born Charles Uksila, a teammate of Victorian-born Tommy Dunderdale in the forerunner of the NHL Blackhawks, probably coached Victoria in the 1923 Goodall Cup federation series against New South Wales. The legendary Jim Kendall was farewelled with a six-test, double-header series split between Melbourne and Sydney in 1925. The official attendance at the second test of the 1926 Goodall Cup in Melbourne was 4,000 people; [167] similar numbers attended local and interstate ice sports carnivals; 15-minute "descriptions" of interstate ice hockey matches were broadcast in the evening on Melbourne radio 3AR by 1926; and by 1930, local matches were broadcast from the Melbourne Glaciarium on radio 3AR. [168]

The third decade was again interrupted by war. The stalwarts of the twenties stood aside for a new generation; and the early thirties saw remarkable progress and development. About 5,000 skaters reportedly attended the opening of the 1931 skating season at Melbourne Glaciarium, some of whom danced in a roped-off waltzing area with a resident orchestra conducted by Frank Bladen. The Victorian Public Schools junior ice hockey competition was founded this year, with Melbourne Grammar School and Wesley and Scotch colleges. These schools, which had figured so prominently in the foundation of ice sports in Australia, were re-introduced on the anniversary of the first quarter-century of ice hockey; the Silver Jubilee of Australian ice sports. Melbourne Grammar defeated Scotch in 1932, and former European ice skating champion, Henri Witte, trained the Victorian ice hockey team for the first time, following his success with the Oxford University team in England in 1931. [208] In the Goodall Cup that year, New South Wales and Victoria won a test apiece and drew the other, 3–0, 1–1, 0–2, although New South Wales held the Cup. [216] Australian ice hockey was innovative by world standards, Interstate clashes were extremely fast and competitive, and New South Wales' unbroken winning streak between 1923–38, the years before Australia joined the IIHF, was not quite as impressive as it appears today. Yet, in the end, Victoria resorted to stealing back the Goodall Cup.

The fourth decade, commencing soon after the Second World War, forged more national and international relations; established the first tentative Olympic affiliations; and raised ice sports in both Mebourne and Sydney to new peaks of popularity and participation. Australia joined the International Ice Hockey Federation in 1938, and the Goodall Cup competition resumed in 1946 after the war. Suddenly, under a unifying authority and International rules, New South Wales' unbroken "custody" of the trophy was ended by Victoria in 1947, after a quarter-century. Victoria dominated the next quarter-century, with twenty Cup wins compared to eight by New South Wales, and one by Queensland. The first junior Interstate ice hockey competition was introduced in 1951 when New South Wales played Victoria during the Goodall Cup series at St Moritz at St Kilda in Victoria. This decade had finally brought with it the last of the National controlling authorities, worldwide affiliations, and the second rinks in both cities; imported ice stars, trainers and managers; and the first fruits of the first generation of Australian International champions. By the fifth decade, Australian ice athletes were training overseas and gaining more recognition on world stages than ever before.

Both Reid's first rinks closed soon after the end of that first half-century; Sydney first, then Melbourne in 1957, the year following the Golden Jubilee of ice sports in Australia. A new era began from the mid-1960s, but with mixed success. New South Wales rebuilt from the ground up during these years, and ice sports eventually spread to almost all States but, ironically, the processes of decline had begun in Victoria, from where they had first started and spread nationally. Despite the unprecedented spate of new rinks there, most proved to be merely speculative and short-lived, and ice sports in the State mirrored their rise and fall. Although Victoria still produced some of Australia's best ice athletes, some had moved Interstate for world-class facilities that were no longer available at home, and participation had dwindled generally to a pale shadow of its foundation years. Elsewhere, administrative innovation and more enterprising approaches had taken some State controlling authorities to new heights of professionalism for amateur ice sports, producing the first semi-professional participants, and some of the best facilities, athletes and leagues Australia had so far seen. Much of that infrastructure still forms the nucleus of Australia's modern ice sports as we know them today, and it was largely inspired by these champions of champions.

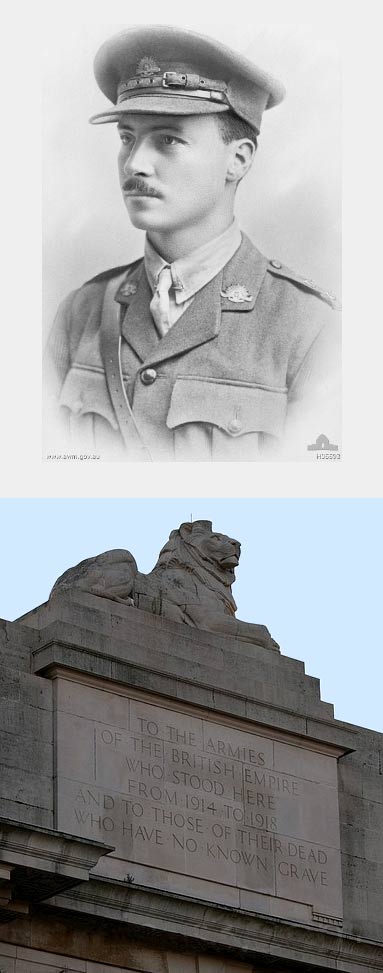

Andrew Lambert Newman Reid

Andy (1889 - 1917)

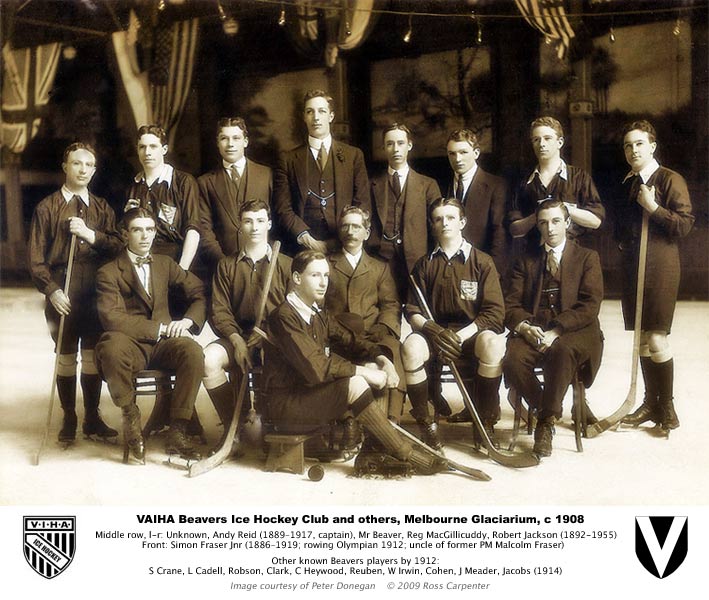

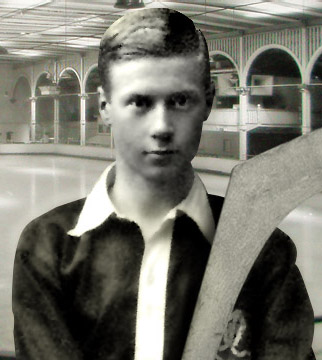

BORN ON SEPTEMBER 21st, 1889 at Hawksburn, next to the Melbourne suburb of South Yarra, eldest son of Henry Newman Reid and his wife Lucy Marsden. He was named after his uncle, a pioneer of Mildura in north-western Victoria who died at the age of 23, the same year Andy was born. A mechanical engineer and soldier, Andy lived at the Reid family home, Locksley at Haverbrack Avenue in Malvern. He was a notable athlete at Melbourne Grammar School (MGS) where he won the football championship and other honours, and came to be regarded by school mates as "one of the best". He represented MGS in the athletic teams of 1907 and 1908, the football eighteen of 1908, and 'he was well-known as a champion ice skater'.

Andy was a volunteer Cadet at Melbourne Grammar and also at St Peter's College, Adelaide, with which it was associated, when the Reids moved there in 1904 to build the Glaciarium Ice Palace. Sir Stanley Melbourne Bruce (1883–1967) commanded the Melbourne Grammar Cadets during Andy's time. Bruce was born at Stadbroke, a few doors from the home of John Goodall's grandfather in Grey Street, St Kilda, and he later became Prime Minister of Australia. Andy attended St Peter's when Rev Henry Girdlestone (1863–1926) was headmaster. Girdlestone was a former stroke of an Oxford Eight, who became acting headmaster of Melbourne Grammar School between 1917 and 1919, and patron of the Melbourne University Boat Club when Barney Allen was president of both it and the National Ice Skating Association of Australia. In 1912, Andy's schoolmate, Simon Fraser Jr, rowed in the first Australian eight to compete at the Olympics. Andy and his brothers probably played bandy at Adelaide in late-October, 1904, "... The advertisement below announces that a "Great Ice Hockey Match" would be played on Wednesday October 12th, 1904. Names of the players are not known, but four of them would have been Mr Newman Reid's sons; Hal, Andy, Les (Snowy) and Dunbar Poole." [2] At that time, Henry was about 42 years-old; Andy was aged 15, Hal was 13, and Leslie was 10.

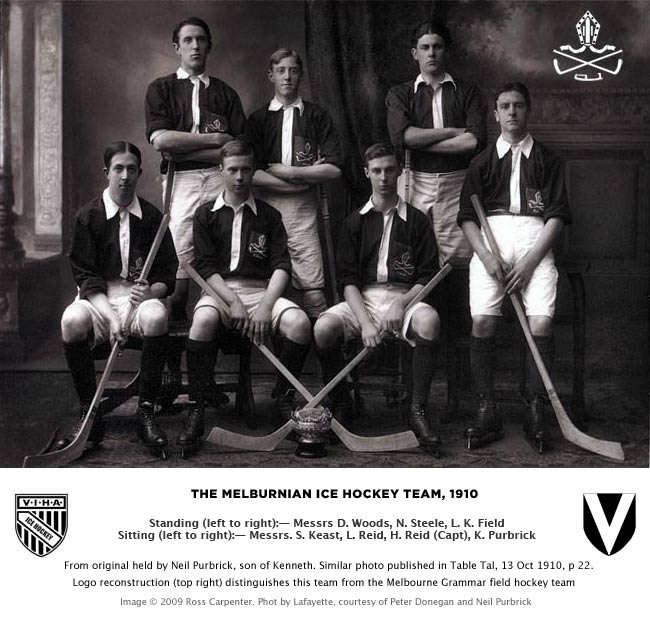

When the first officially-recognised ice hockey game in Australia was played in Melbourne in 1906, Andy did not play. He was only 16 years-old but his father had established the first suitable surface for ice hockey in Australia that year, and by the outbreak of the First World War, he would inaugurate the first phase of the sport's development through Andy and his brothers, and their links with Melbourne's earliest Anglican schools. The schools the Reids attended had been established by early colonists who had benefitted from the Public Schools they attended in Britain, and who wanted equivalent institutions for their sons. The first ice hockey clubs in Australia were formed from them — the first Australian club team in 1907, simply named Melbourne Glaciarium, and in 1908 Melburnians IHC, Beavers IHC and Brighton IHC; the original four. They were joined by Ottawa IHC in 1910. Andy matriculated in 1907 with Physics honours from Melbourne Grammar School and did his Senior Public in 1908. Andy was captain of Beavers IHC from inception and its top goal-scorer. [278] This club competed between 1908 and 1921, never winning a VIHA Premiership.

Andy represented Victoria in the first match played against New South Wales at Melbourne in 1909. [1] New South Wales won the first game 1–0 but lost the other two 0–1 and 1–6. Andy was about 18 years-old, and he played for Victoria against New South Wales again the following year in Sydney; the first Interstate match played by Victorian John Goodall, donor of the Goodall Cup. Victoria won the first two Cups with Andy in these years, and then lost in 1911 and 1912, the years Jim Kendall first represented New South Wales. Victoria won again in 1913 with Andy and his brother Leslie, [279] then interstate ice hockey was interrupted by war for six years. In his prime, Andy was 5-feet 7 1/4-inches tall (171 cm), with a 35- to 37-inch chest and weighed 142 pounds (64.4 kg). He had a fair complexion, brown eyes and dark brown hair. Three scars on his left arm and shoulder blade, and one on his left knee, just might have been stick or skate-blade injuries. He attended university shortly after 1909 and became a refrigeration engineer like his father, with whom he had probably briefly worked at the Melbourne Ice Skating & Refrigeration Co. Years later, a newspaper obituary noted, "...after leaving school for the 'Varsity he won the ice skating championship and other Glaciarium prizes". His younger brother, Hal Reid, was the first NISAA National skating champion on record in 1911, when Dunbar Poole was overseas. Andy was the National champion two years later in 1913. [377]

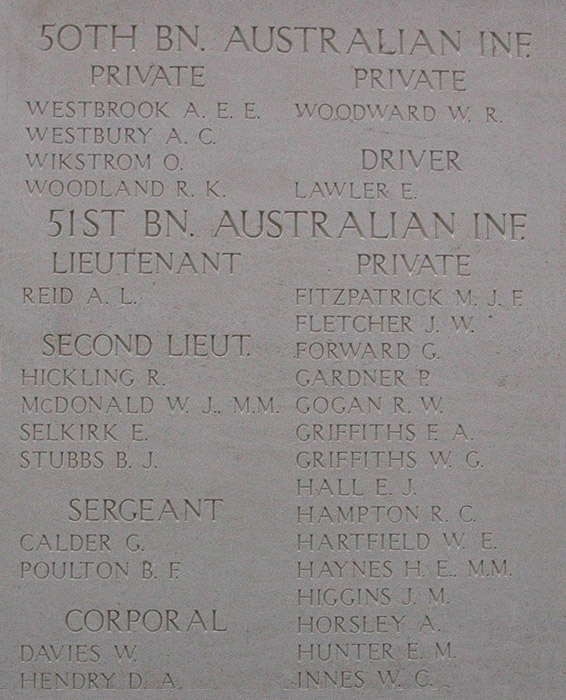

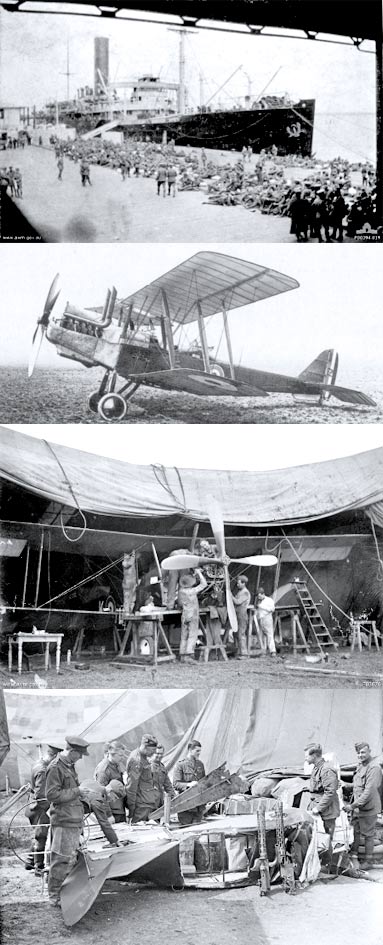

By 1911, Australia had seven ice hockey clubs, three in Sydney (New South Wales) and four in Melbourne (Victoria). In the years between 1911 and 1929, Australian men aged between 18 and 60 were required to perform militia service. Training and service had been compulsory in time of peace since 1911, and the Government was empowered to call up 'unexempted’ males in time of war. All three Reid boys had to train and serve in the army at some point, but Andy had chosen to soldier earlier in the Commonwealth Cadet Corps in Adelaide and Melbourne, for two years from the age of 13 or 14. He entered Duntroon Military College about 1913, just two years after it had been established on the old Campbell family homestead in Canberra. Duntroon was modeled on the Royal Military College of Canada, and the military colleges of Britain and the United States. There he gained a commission as 2nd Lieutenant on June 5th, 1915, graduating with a Diploma of Arts (Military) after completing the 18-month military and academic course. He served seven months as Provisional Lieutenant and six months as a Lieutenant with the 48th Kooyong Infantry of the Australian Citizen's Military Force (CMF), now the Army Reserve. He enlisted on January 18th, 1916 with D Company of the 38th (Bendigo) Infantry Battalion and transferred from the Royal Park Depot to Bendigo. Sir George Victor Lansell (1883–1959), a former Melbourne Grammarian, became its captain in May 1916. Andy subsequently transferred to 49th Battalion, and left Australia on A54 Runic on June 20th, 1916. He was attached to the 51st Battalion and proceeded to France in October where he served throughout the winter, and where he was promoted once again to Lieutenant a few months later. He spent a few days leave in London immediately prior to going into action at Messines.

Oddly, Andy had resigned his officer commission and re-enlisted in January, 1916 as a Private, then a Sergeant, in the same Battalion. This story is more accurately described in another of his obituaries, "Enlisting soon after war broke out, he soon earned his stars; but finding that owing to a surplus of junior officers he would be detained in camp for some months, Andrew Reid resigned his commission and re-enlisted in order to get to the trenches with his pals. When the newly enlisted ex-officer marched back to camp the whole place rang with cheers and applause. But the lost commission was soon picked up in the trenches. Liuet Andrew Reid died as he lived — a sport in the highest sense of the word." Andy was killed in action on the boggy, shell-torn and poisoned Messines Ridge, fighting for Belgium’s freedom. The conditions made that battle a byword for suffering, and few landscapes are more redolent of war. Over 850,000 died there, including 325,000 British soldiers. He was 27-years-old when he was killed on June 9th, 1917. He was buried West of Yaer Canal on the northern outskirts of Ypres (now Ieper), West Flanders, Belgium and he is listed on the Menin Gate Memorial at the eastern exit of the town, 'REID, Lt Andrew Lambert, 51st Battalion, 9th June 1917, Age 27. Son of Henry Newman Reid and Lucy Reid, of 9 Blackfriars St, Sydney. Native of Melbourne.' [97, 99] Since the 1930s, with the brief interval of the German occupation in the Second World War, the City of Ieper has conducted a ceremony at the Memorial at dusk each evening to commemorate those who died in the Ypres campaign.

Messines was considered a strong strategic position, not only from its height above the plain below, but from the extensive system of cellars under the convent known as the 'Institution Royale.' The village was taken from the 1st Cavalry Division by the Germans in November, 1914. An attack by French troops in November, 1916 was unsuccessful, and it was not until June, 1917 at the Battle of Messines in which Andy was killed, that it was retaken by a New Zealand Division; perhaps the first clearcut British victory. Now marked on maps and signed as Mesen, there is a well-known sequence of aerial photographs that show, over a few months, the total destruction of this village. It was ground into dust. Andrew Reid's name is also carved on the Great Cross at Messines Ridge British Cemetery, on the Nieuwkerkestraat road at Mesen in Belgium.

Trained from the age of 14 by Dunbar Poole; Professor Brewer, the professional world skating champion from Prince's Skating Club in London; and such players as Australian roller skating champion John Caldwell and Canadian Herbert Blatchly, the captain of Australia's first ice hockey team, Andy Reid had developed into an exceptional ice sports athlete within a few short years. The peer respect he earned helped to introduce other athletes to his father's enterprise. It was through Andy Reid that Australia's fledgling ice sports first gained access to grammar school and university athletes. He was 14-years-old when the first experimental rink opened for a year in Adelaide; 16 by the time Melbourne Glaciarium opened; and not quite 18 when he represented Victoria in the first Interstate series in 1909. He played an active role in the formation of that first Victorian team, and in the very first ice hockey clubs in Australia. He was among the first few Australians to develop skating and hockey skills locally, and to a standard that won both Victoria and he, some of the very first championships during the start-up years of Australia's first ice rinks. Although his life was foreshortened by the Great War, and he neither married nor competed internationally, Andrew Lambert Reid was Australia's first home-grown ice champion.

Historical notes:

[1] Andy's Battalion, the 49th, was first raised in Egypt on February 27th, 1916 as part of the “doubling” of the AIF. About half of its recruits were Gallipoli veterans from 9th Battalion, and the other half, fresh reinforcements from Australia. It became part of the 13th Brigade of the 4th Australian Division. The 49th arrived in France on June 12th, 1916, then moved into the trenches of the Western Front for the first time on June 21st. It fought in its first major battle at Mouquet Farm in August and suffered heavily, particularly in the assault launched on September 3rd. The battalion saw out the rest of the year alternating between front-line duty, and training and labouring behind the line. This routine continued through the bleak winter of 1916–17. Early in 1917, the battalion participated in the advance that followed the German retreat to the Hindenburg Line, supporting the 13th Brigade’s attack at Noreuil on April 2nd. Later in the year, the focus of the AIF’s operations moved to the Ypres sector in Belgium. There the battalion fought in the battle of Messines, which claimed Andy's life on June 9th.

[2] Melbourne Grammar School, also known as MGS or Melbourne Boys, is an independent, day and boarding school predominantly for boys', located in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. Founded in 1858, the school is a member of the Associated Public Schools of Victoria. It is associated with the Anglican Church of Australia, and was formerly named Melbourne Church of England Grammar School. From the start it was exclusive, catering to the young gentlemen of rich immigrant English and squatter families, and originally the student body consisted only of boarders. The junior school (years prep to 6), Grimwade House, is co-educational. It is located in the suburb of Caulfield, east of Melbourne city itself, and is named after the Grimwade family, who in 1918 donated the land and house for the use of the school. All the Reid children had completed their schooling before it opened. The waiting list at Grimwade was huge — if not enrolled at birth, there was no chance of ever attending. Whilst Grimawade has long catered to students of both sexes, the Old Melburnians have resisted any moves to inroduce girls to either the middle school (Wadhurst) or the Senior School. Of 1,327 Old Melburnians who enlisted in the Great War, 207 or 1 in 6 were killed. There were nine Melbourne Grammar families who lost more than one son.

[3] Melbourne Grammar was of seminal importance to Australian Rules football. It provided one of the two participating teams for "a grand football match", commencing on August 7th, 1858, and ending, after several sessions of play, almost a month later. This match is considered the direct progenitor of the modern game of Australian Rules football. The MGS Old Melburnians football club was later formed in the Victorian Amateur Football Association (VAFA) at Junction Oval St Kilda in 1920. See Reginald Wilmot

[4] St Peter's College is an independent boy's school in Adelaide, South Australia. Founded in 1847, also by members of the Anglican Church of Australia, the school is noted for its famous alumni, including three Nobel laureates and forty-one Rhodes scholars. Three campuses are located on the Hackney Road site near the Adelaide Parklands in St Peters. It was established two years before St Peter's College at Eastern Hill in Melbourne, forerunner to Melbourne Grammar School.

[5] The advertisement referred to above appeared in the Adelaide Advertiser on Tuesday October 11th, 1904 according to research by Ray Raines, Department of Trade and Economic Development, SA. Tange claimed this date was supported by early programmes. [2] A 'proposed' ice skating rink is discussed in the Advertiser, p 6e and The Register, p 3e on June 3rd, 1904. Actual photographs of Adelaide Glaciarium are in The Critic, May 24th 1905, p 6, and August 9th, 1905, pp 8, 9. The first newspaper account of ice skating there is in June 1905, and the first hockey match on an ice skating rink is reported in the Express, July 5th and 12th 1905, pp 2d, 2e.

Henry Newman Reid Jr

Hal (1891 - 1942)

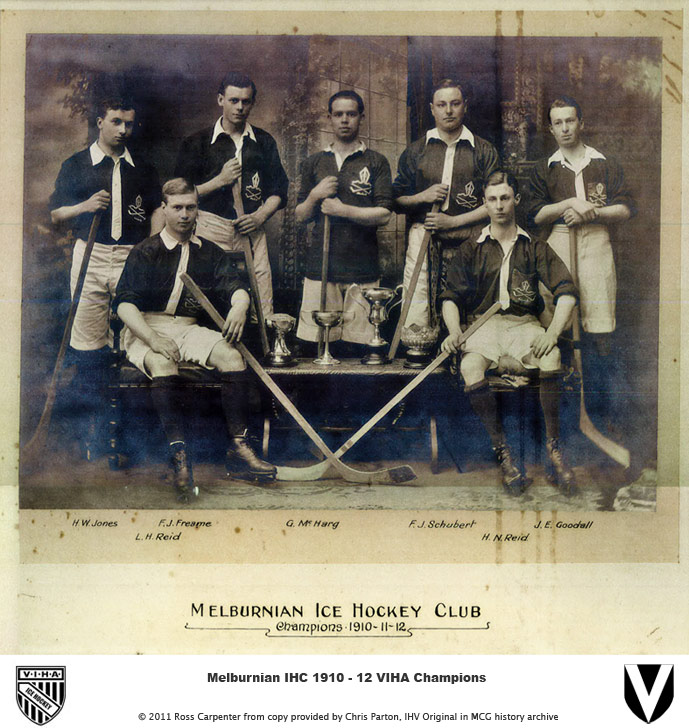

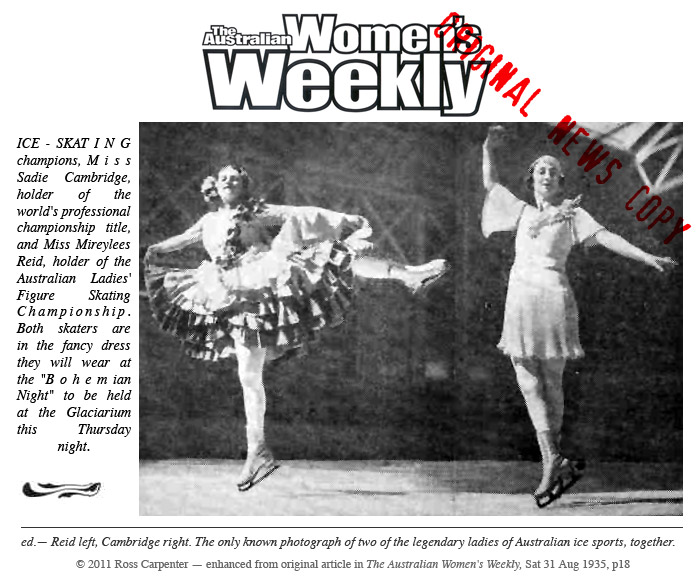

BORN IN 1891 IN BRIGHTON, second son of Henry Newman Reid and his wife Lucy Marsden. Hal lived at Brighton in Melbourne and the Reid family home, Locksley at Haverbrack Avenue in Malvern. He attended St Peter's College, Adelaide, in 1904–5 and Melbourne Grammar School with his brothers, two years behind Andy, and three years ahead of Leslie. Hal was first trained by Professors James Brewer, Claude Langley, and John Caldwell and also no doubt by Dunbar Poole. He played bandy in Adelaide with his brothers and when he returned home to his father's new competition-size rink, he became the first captain of Melburnian Ice Hockey Club in which his younger brother Leslie and John Goodall also played. Melburnians dominated the first league for over a decade, winning every contest on record from 1909 to 1913, and two after the war in 1922–3 as Melbourne IHC. Hal competed in the 1909 and 1910 Goodall Cups won by Victoria from the age of eighteen, and the 1911 and 1912 Goodall Cups won by New South Wales in which Jim Kendall played his first two seasons. In 1910, Hal won the one mile speed skating interstate championship over his brother Andy and others. [393] In 1911, he won the men's figure skating event in the inaugural NISAA "Nationals", and he was still captain of Melburnian IHC in 1913. Hal positively shone, yet it appears he did not return to the sport after the long war interruption. He married soon after and for the first time none of the Reid founders were directly involved in Victorian ice hockey.

Unlike his two brothers, Hal did not enlist for active service, and little is known about his life during these years, although he was the only family member to remain in Melbourne. Correspondence related to his brothers' war service held at the National Archives, includes a hand-written note with the contact details: "Brother: Mr H N Reid, Private: 6 Elwood Street, Brighton, S5 X4471; Business: 23 Grant Street, South Melbourne." His Grant Street business address was located nearby the Glaciarium in City Road where his father also operated cold stores. His Elwood St residence was near the foot of North Road in the heart of Brighton where his brother Leslie was born. Hal lived there until his death.

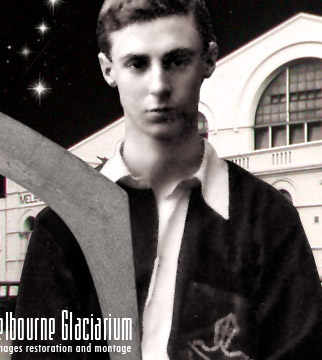

The burnt-out Glaciarium had reopened by 1919, not 1922 as recorded in ISA history, and the Victorian Ice Hockey Association had reformed by 1920, starting virtually from scratch. Irreplaceable records including the rules had been lost, gear and equipment was gone, and players had drifted away, some never to return. Still, unofficial games were played in Melbourne in 1920, and all preparations were aimed at soundly rebuilding the sport in the bigger and better Glaciarium for the 1921 season. [1] It was a new rink, a new Association, a new era; and at the centre of all this change were John Goodall, Ted Molony, Jack Gordon, Cyril MacGillicuddy and rink manager Leo Molloy, who held his postion until the Glaciarium closed in 1957. Although Hal Reid did not return to the sport, he remained a friend of John Goodall for a long time. In 1924, Hal, Goodall, and Hal's brother Leslie in Sydney, floated a public company with a capital of £15,000. They were the first directors of Galvanised Products Ltd at Glebe in Sydney, manufacturers of sheet metal products. Leslie Reid was Managing Director until his early death in 1932. [395]