Legends

home

1936 1st AUSTRALIAN Winter Olympian

1947 1st International Figure Skating GOLD Medallist

1960 1st Australian Olympic and World Championship ICE HOCKEY Teams Squaw Valley California USA

1961-2 2nd AUSTRALIAN Ice Hockey World Championship Ice Hockey Team Colorado USA

1963-4 2nd OLYMPIC Qualification ICE HOCKEY Team Tokyo Japan

1987 1st International Ice Hockey MEDAL Perth Australia

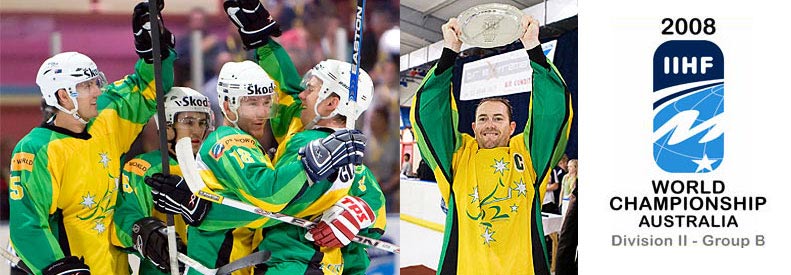

2008 Ice hockey World Championship PROMOTION TO DIVISION I Newcastle Australia

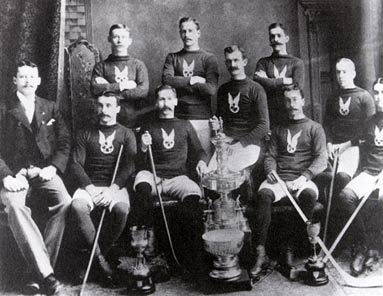

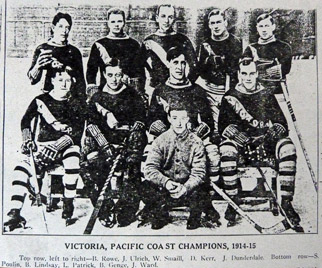

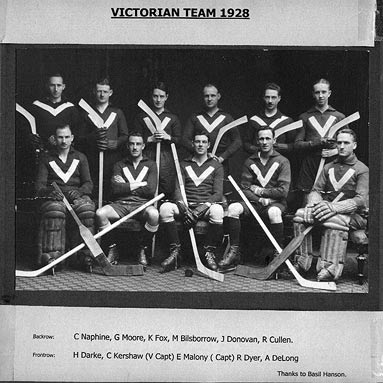

The First Ice Hockey Champions

Melbourne, 1960

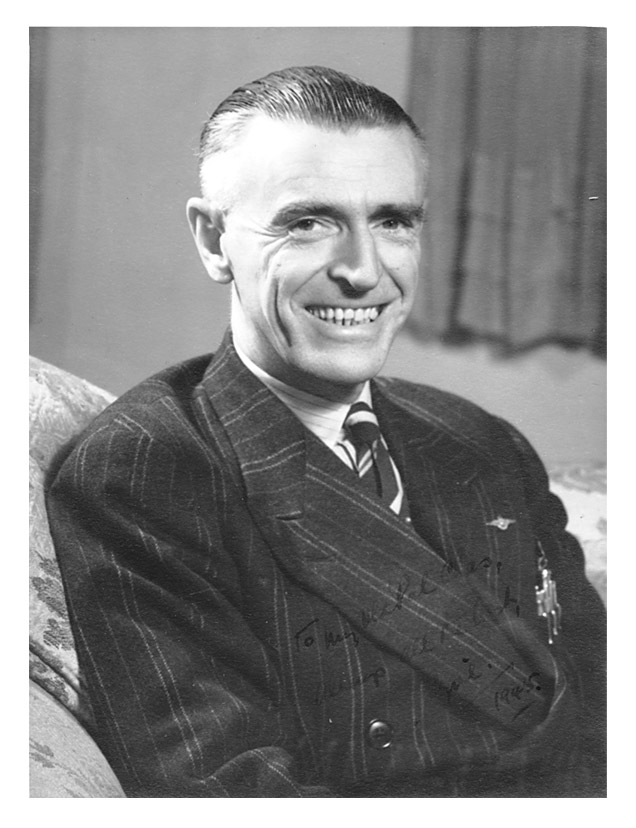

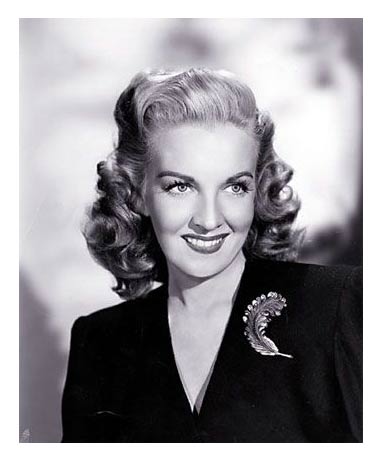

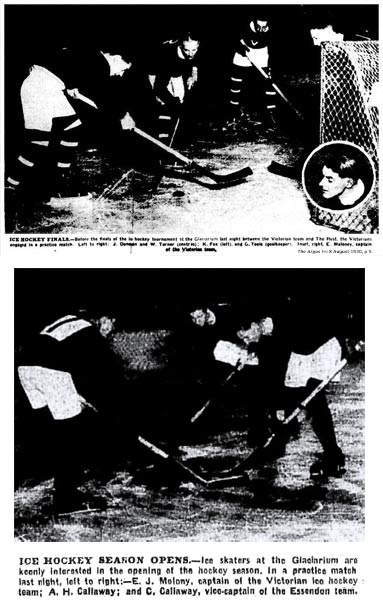

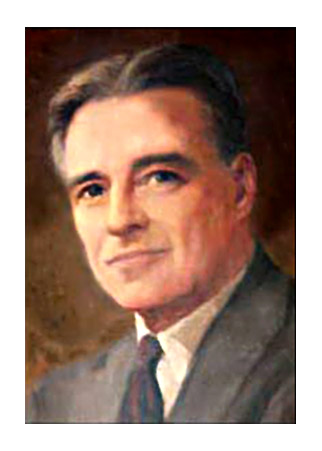

FTER THE 1960 WINTER OLYMPICS, in which Australia's only ever ice hockey team was soundly defeated, there was debate about the trade-off between selection standards and participation. Ken Kennedy was President of both the New South Wales and Australian Ice Hockey Federations at the time of the Games. At a 1963 meeting, he complained that the ice hockey team was not given trips because they were not world class, yet could never become competitive unless they had overseas matches. Edgar Tanner, a member of the Australian delegations to six Olympiads (1952-76), said "I ask the winter sports whether they really believe they are in world class, or world ranking, in the field of sport and whether they can do Australia credit, or just be there." Bill Young, manager of the cycling team, disagreed, saying "I thought the first spirit of the Games was to compete". [22] A quarter of a century earlier, Kennedy had left Australia at age 21 to train overseas, and that led to his selection as the sole member of the first Australian Winter Olympic team a few years later in 1936. He had also played for Birmingham Maple Leafs IHC during those years, at a time when the Club was part of the biggest amateur league in the world, and won the English League Championship. In fact, Britain captured the Triple Crown of World, Olympic and European ice hockey titles in 1936. Kennedy turned professional in England after the Olympics, and served in the RAF during the War.

FTER THE 1960 WINTER OLYMPICS, in which Australia's only ever ice hockey team was soundly defeated, there was debate about the trade-off between selection standards and participation. Ken Kennedy was President of both the New South Wales and Australian Ice Hockey Federations at the time of the Games. At a 1963 meeting, he complained that the ice hockey team was not given trips because they were not world class, yet could never become competitive unless they had overseas matches. Edgar Tanner, a member of the Australian delegations to six Olympiads (1952-76), said "I ask the winter sports whether they really believe they are in world class, or world ranking, in the field of sport and whether they can do Australia credit, or just be there." Bill Young, manager of the cycling team, disagreed, saying "I thought the first spirit of the Games was to compete". [22] A quarter of a century earlier, Kennedy had left Australia at age 21 to train overseas, and that led to his selection as the sole member of the first Australian Winter Olympic team a few years later in 1936. He had also played for Birmingham Maple Leafs IHC during those years, at a time when the Club was part of the biggest amateur league in the world, and won the English League Championship. In fact, Britain captured the Triple Crown of World, Olympic and European ice hockey titles in 1936. Kennedy turned professional in England after the Olympics, and served in the RAF during the War.

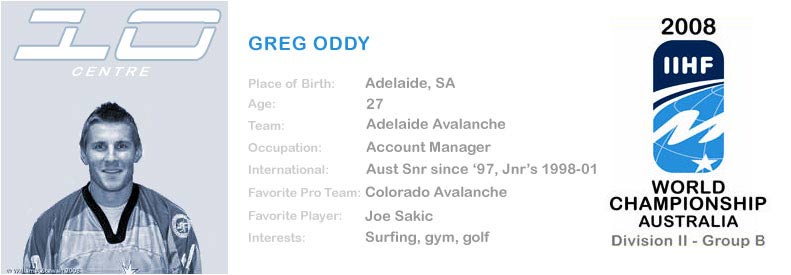

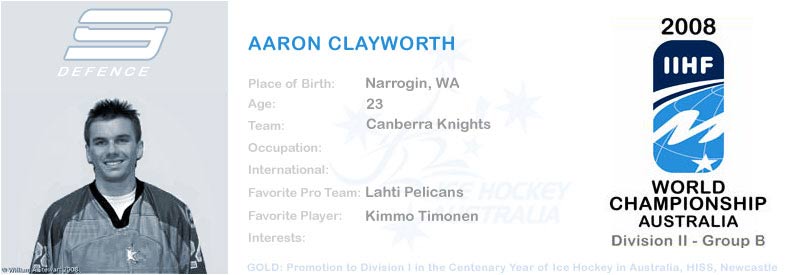

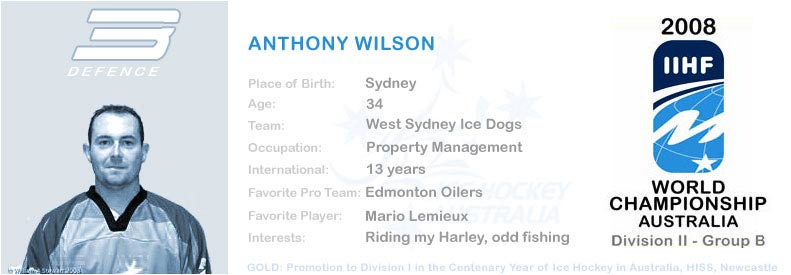

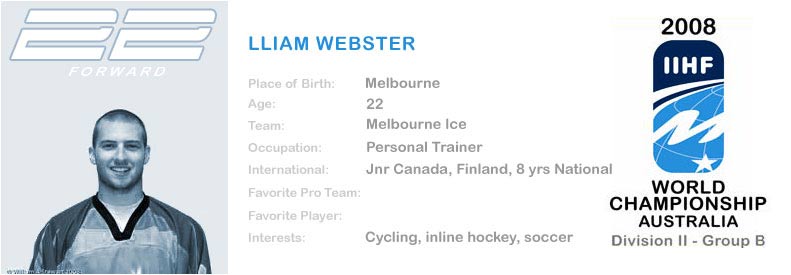

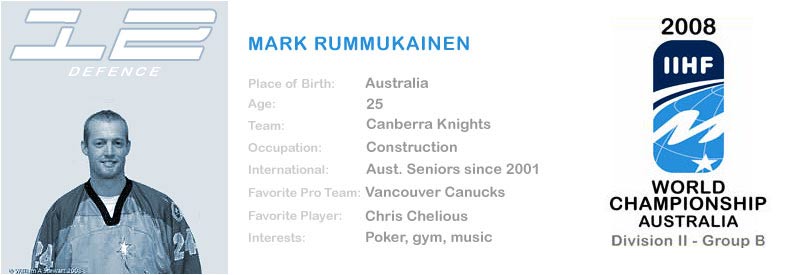

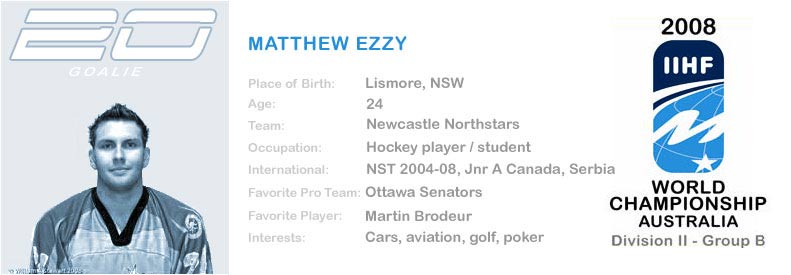

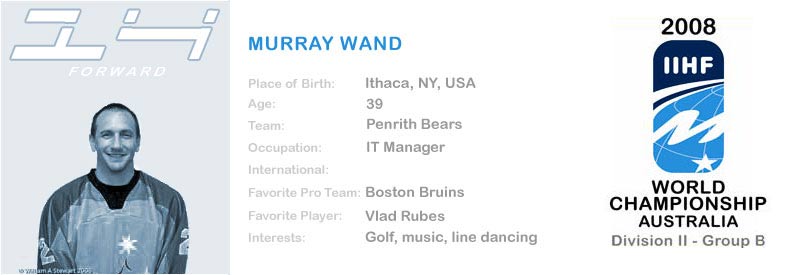

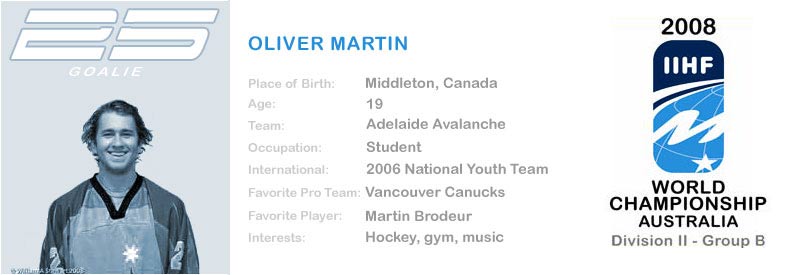

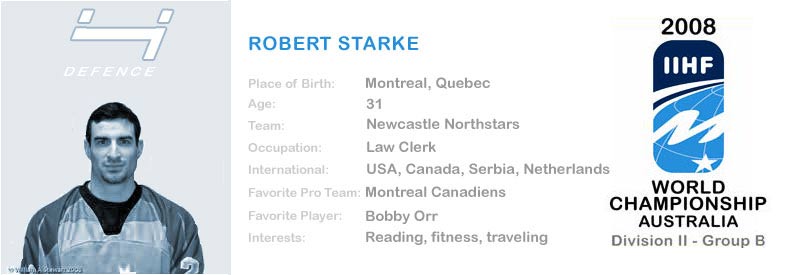

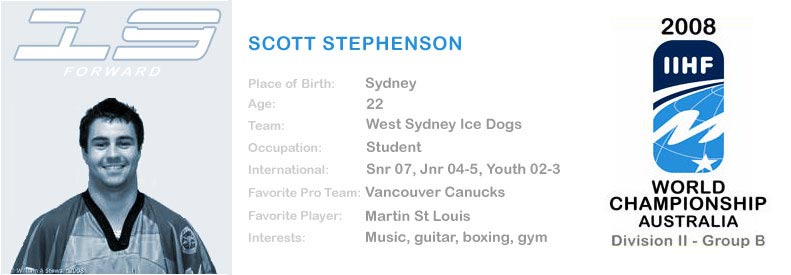

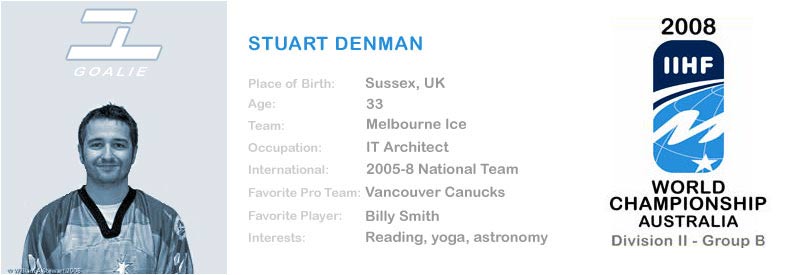

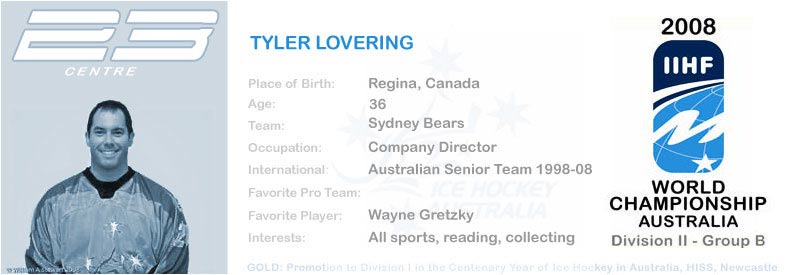

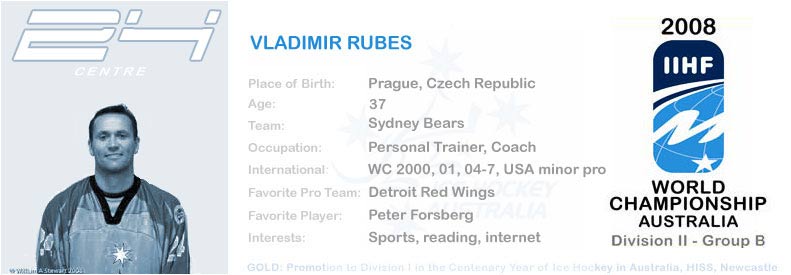

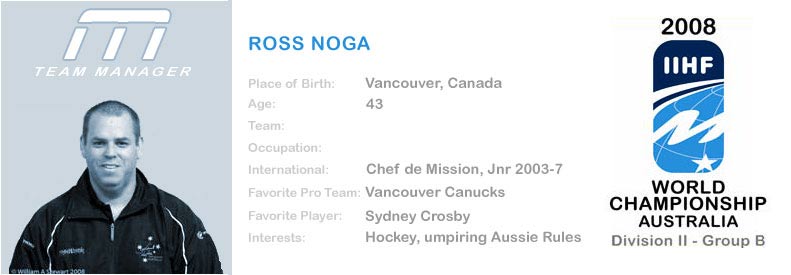

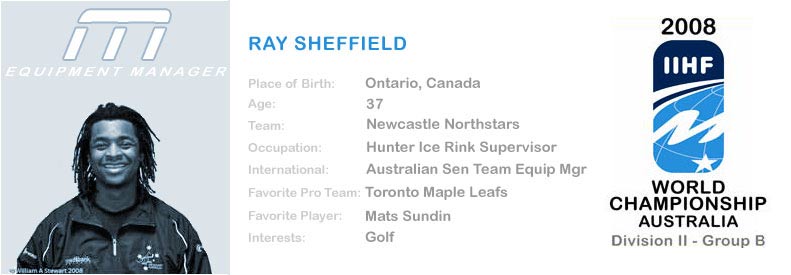

Harold Luxton died the year after the Melbourne games, and both Lewis Luxton and Kennedy died in 1985, two years before Australia won its first ever international ice hockey medal. But if you look very closely, they are there between the images in the viewer above. They are the players and officials of the 2008 Mighty Roos ice hockey team, who won gold on home soil at the world championships in Newcastle, NSW. All the team coaches and managers were born in Canada, along with four players. Two other players were born in the US, one in England, and one in the Czech Republic. But a majority of fifteen including the captain were born locally, and most had international hockey experience. They were promoted to Division I for the first time in history in the centenary year of Australian ice hockey. Australia has now competed with the elite Division I Group A ice hockey nations of the world. It is within one place in the World rankings of qualifying an Olympic ice hockey team once again (note 1 below).

Yet it was a very long line of Australian International champions who preceded them. In fact, there were over eighty in the first generation produced by Reid's rinks alone. Among them were Kennedy himself, the first Australian Winter Olympian, the 1st Australian Olympic and World Championship ice hockey teams, members of the Olympic Southern Flyers Ice Racing Club founded in 1949, speed skater Colin Hickey, and International ice show stars and skating champions such as Pat Gregory, Jack Lee, Reg Park, the Brown, Molony and Burley families, and expatriate skating pair, Enders and Cambridge. Many became local and International coaches and judges. They and their protégés placed Australia on the Winter sports map, with little or no public funds or assistance.

Notes:[1] Twelve teams qualify for the Winter Olympics Ice Hockey event, based on their IIHF World Ranking after the Men's World Ice Hockey Championships the prior year. The top nine receive automatic berths and the other three are determined using a qualification system for the 16 teams in the top Championship Division and the 12 teams in Division I. Mighty Roos were relegated from Division I to Division IIA in 2012, narrowly missing the opportunity for qualification for the 2014 Games at Sochi, Russia.

[2] Bill Young AM MBE, who thought "the first spirit of the Games was to compete," was one of two inaugural Life Members of the Australian Cycling Federation in 1979.

Ernest James KENDALL (Jim, Kenny)

(1889 - 1942)

JIM KENDALL WAS BORN ON FRIDAY 13th, IN DECEMBER 1889 at Sydney, Nova Scotia, the only son of Ida Burchell (1862 – 1909) and Lieutenant Colonel Dr Henry Ernest Kendall MD (1864 – 1949), who became Lieutenant Governor of Nova Scotia in 1942. [32, 59, 66, 68] His father, a physician, farmer and politician, was the younger son of London-born Emily Long (1823 – 1908) and Bristol-born Reverend Samuel Frederick Kendall (1818 – aft 1908). Samuel, a member of the Plymouth Brethren, helped establish the Union Church on Mitchell Island in 1866, on the north-west arm of Sydney Harbour. He attended meetings at the Baptist Church in Sydney, performed marriages and held bible study classes in a small meeting house which he built in front of his home at the corner of Charlotte and Pitt Streets. [73] His wife, Emily Long, was a supporter of Dr Barnardo, a social reformer who worked in the slums of London, and established orphanages throughout the United Kingdom. [73] Jim's uncle, Arthur Samuel Kendall (1861 – 1944), was a physician and politician like his brother; MLA, MP as well as Medical Health Officer for Cape Breton and a prominent social reformer. [63] This family emigrated from England to Sydney, NS in 1857, when it was a town of only 700 settlers drawn from all all over the UK and the neighbouring colonies. [73] In 1901, Jim lived at Sydney with his parents, younger sister Helen, and other relatives. The steel plant opened that year when he was 12, and it rapidly transformed Sydney into “the steel capital of Eastern Canada” for a century. [32]

Kendall became a steel manufacturer, [59] working at the Dominion Iron and Steel Co in Sydney, NS, during summer breaks, and perhaps also at the Nova Scotia Steel and Coal Co which was built nearby at the same time. Production was at its peak around the time he was old enough to work, and a 20-year long industrial unrest and stikes had begun around the time he left Canada. Some say he was from Halifax, the capital of Nova Scotia, about 300 km south-west of his hometown, but only his father moved there, and not until after Jim had left Canada. He first developed hockey skills in Sydney — in the amateur Maritime Hockey League (MHL) operating in Nova Scotia around 1900, and perhaps even its forerunners. Coincidentally, Bud McEachern played in the MSHL for Sydney Millionaires IHC, later in the 1940s. The MHL is notable for several Stanley Cup challengers including Sydney Millionaires. It evolved into the Maritime Professional Hockey League as part of the progression of elite amateur ice hockey leagues to paid professionals around 1910. [65] It was the first of the early recognized pro leagues formed from the Interprovincial Professional Hockey League 1910–11 season.

By 1908, the amateur and professional ice hockey teams of the Eastern Canadian Amateur Hockey Association (ECAHA) had separated, and the Inter-Provincial Amateur Hockey Union (IPAHU) became the premier amateur league in Canada. The Stanley Cup remained with the pro leagues and Sir Montagu Allan donated a new championship trophy for amateurs. The IPAHU's four-team league was Montréal's Victorias and Montréal AAA, Ottawa's Cliffsides and Toronto's AAC. It commenced in 1909 after Kendall had left Canada, and Montréal Victorias were given the Allan Cup to present to the champion of their league, who could then be challenged. Competition from the West didn't exist in these early days, although Winnipeg had formed an amateur hockey league in 1891. Senior amateur hockey in Canada at that time was more popular than the professional teams which only ever represented a handful of Canadian cities. Virtually every community of any size across Canada could and usually did ice a senior amateur team, and most consisted of "community players" born and raised where they played hockey.

Kendall was 19 years old when the amateur IPAHU was founded and it has been said he was offered a cadetship with the "Montréal Professional Club" in Montréal, Québec, the largest city in Canada at the time, nine hundred miles west of Sydney, NS. [2] The NHL was not formed until 1917, years after Kendall had left, but it had developed from many earlier professional leagues, including the short-lived Manitoba Professional Hockey League in which Montréal Wanderers played in 1906 and 1907, from home ice at Montréal Arena. They won eight Stanley Cup challenges 1906-10 to become one of the most successful pre-NHL clubs. Another, Montréal Hockey Club (aka Montréal AAA and Montréals), one of the four original IPAHU teams, competed in the purely amateur leagues until 1906, but turned professional for two seasons, then left the ECAHA for the amateur IPAHU. Their home ice was Victoria Skating Rink, Montréal, now officially regarded by the International Ice Hockey Federation as the birthplace of organised ice hockey. They won the first Stanley Cup in 1893, only to refuse it in a dispute with the MAAA, then again in 1894, 1902 and 1903. Montréal also iced the Canadiens, Nationals, All-Montréal HC and Shamrocks teams in various pro leagues from the 1909-10 season, but Kendall was already on his way to Australia via Liverpool, England. [80]

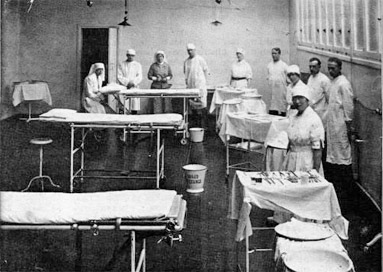

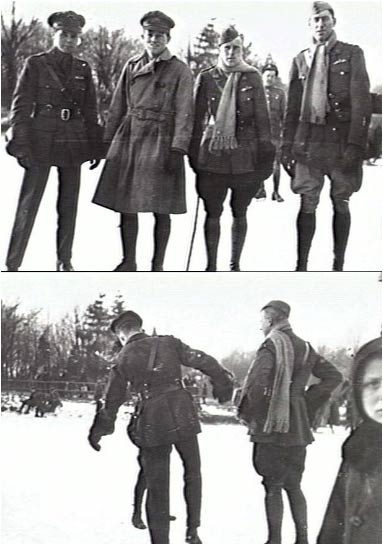

Jim's sister, Helen (1892– aft 1983) was born on November 29th, 1892 and she trained as a nurse with the Royal Victoria Hospital, near McGill University in Montréal with which it is affiliated. [68, 74, 80] She was old enough to attend from about 1907, traveled overseas during the war years, then worked in the hospital's operating theatre on her return. She later enlisted as a nursing sister in the Canadian Army Medical Corps on January 21st, 1917 when she was 24 years-old. [68] Her residence at that time was her father's address at 52 Morris Street in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Helen was an anesthetist in a war when, as she had said, "...the skills of doctors were too valuable to be tied-up administering anesthetics". These women served in hospitals in England, France and the Eastern Mediterranean at Gallipoli, Alexandria and Salonika and upon Hospital Ships. Helen was based in France across the Channel from England and at the 16th Canadian General Hospital at Orpington in Kent England (image right). [398] This hospital was one of the largest and most up-to-date military hospitals in the world in its heyday, treating more than 15,000 wounded soldiers between 1917–1919. Helen was awarded the Royal Red Cross (ARRC) for exceptional services in military nursing. This was one of 446 awarded to Canadian women who were fully trained nurses who had shown special devotion and competency in the performance of nursing duties over a continuous and long period, or who had performed some very exceptional act of bravery and devotion. Up to five percent of the total establishment of nurses could receive the ARRC. [68]

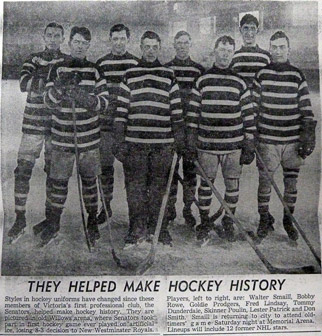

Many Montréal Wanderers had been members of the 1902 Montréal Hockey Club team, and it is quite conceivable that either club offered to take Kendall on as a rookie around this time. Instead, he left Canada for Australia, where amateur ice hockey had only just begun, and pro hockey did not exist at all. In 1910, Australian-born Tommy Dunderdale (1887–1960) joined Montréal Shamrocks at Victoria Skating Rink. It was sixteen years earlier in 1894 that Dunderdale had moved from Australia to Québec, and later Ottawa where he played in his Waller Street School team from 1904. Herbert Blatchly had also played ice hockey in Ontario leagues before he too immigrated to Australia and became captain of the first Australian ice hockey team in 1906 (see Tommy Dunderdale). In the early 1920s, Dunbar Poole, another player from that first Australian team, became a figure skating instructor at Minto Skating Club in Ottawa. Since 1904, this club had held National skating championships at the Rideau Skating Rink in which Dunderdale's school team played. In 1905, Dunderdale moved to Winnipeg, Manitoba and played the 1905–06 season with the amateur Winnipeg Ramblers. It was there that he first turned professional with Winnipeg Strathconas for three seasons, from 1906 to 1910, before moving to Montréal. Kendall had been offered a professional cadetship with a Montréal club a season or two before Tommy Dunderdale joined Montréal Shamrocks and, coincidentally, both were in the same places at about the same time as Blatchly, and later Poole.

Kendall may have planned to return to Canada, but it is also true that his family circumstances had changed dramatically. His grandmother, Emily, died in 1908 and his mother, Ida, died seven months later in 1909, when she was 49 years old. Jim was 19 and somewhere at sea between South Africa and Australia. [68] Both Emily and Ida had been active members of the Baptist church in Sydney, and both were well-known for their charitable acts. [73] His father Henry was approaching fifty, still a practising physician, but with farming and other interests. Henry was attracted to Margaret, who was half his own age and daughter of the wealthy industrialist and influential Canadian Senator John S McLennan. They married in 1913, at the McLennan's Petersfield estate, three years or so after Jim's mother had died and he had left the country. The Kendalls had been long-time family friends of the McLennans. Jim was very close to Margaret's brother Hugh McLennan (1887–1915), with whom he worked at the steel plant in the summers. [80] Similarly, Jim's sister, Helen, was a close friend of Margaret's sister, Katharine. They were the same age and they had played together since they were small and Helen spent most of her holidays from nursing school in Montréal with the McLennans. She often stayed at their Petersfield estate, across the harbour from the steelworks, especially after her mother died. She had acted as her father's hostess since then, and his marriage to Margaret was an upset. [80] Still, she remained Katharine's life long friend, a constant companion on Katherine's excursions, and on holidays at her summer homes in Ben Eoin and Ingonish. Neither married and, although they never lived together, they were quite inseparable. Helen was an immensely vibrant and energetic woman who led a comfortable but modest life-style compared to her father and friends. [74]

Jim's step-mother was just a few months older than Jim himself [68] — the sister of both his and Helen's best friends since childhood. While his father moved on to Halifax with his new bride, Jim's sister Helen and their uncle Arthur remained all their lives in Sydney. His father's branch of the family became part of the upper class with interests in collecting antiques and paintings, and in the lives and stately homes of their family in Canada, the US and England. Helen's friend, Katherine, served as a wartime nurse, but it appears that her work was done in the spirit of patriotic duty and paternalism, unlike Helen's commitment to nursing as a vocation, and certainly unlike Arthur Kendall's abiding and outspoken commitment to radical reform. Jim's step-brother, John, son of Henry and Margaret, felt a rift between the Henry and Arthur sides of the family, and it seems that their chosen careers made them socially distinct, and personally distant from each other. [73] Jim's father was a Mason, a member of the Independent Order of Oddfellows and of the Sydney Club, a private professional men's club of which he was President for at least one term. He berthed his cutter at the Royal Cape Breton Yacht Club, and served as its Vice-Commodore in 1901.

On the other hand, his uncle Arthur was a part of a professional middle class in Sydney and, although he too was a member of the Sydney Club, he was not a member of the wealthy and elite, which included many of the investors in the Dominion Iron and Steel Company, such as J S MacLellan and his associate A J Moxham, its American-born, first general manager. Arthur had married Mary, a daughter of the well-established Crawley family of Sydney. Her great-grandfather was Captain Thomas Crawley, a former Surveyor-General of Cape Breton Island, and her father was Baptist minister Rev Arthur Crawley. She was active in the church with Jim's mother and grandmother until their deaths. Around the time Jim set out for Australia, his uncle was MLA for Cape Breton, with a seat in the House of Assembly at Halifax. Arthur's different social interests were well-publicised and included fighting poverty caused by the rapid industrialisation of Cape Breton, improving living conditions, and lobbying for old-age pensions, a shorter work week and a workmen's compensation act. He acted as a conduit between the working class and the owners of the steel plant and coal mines. [73] The steel industry in Cape Breton, as elsewhere, was extremely dangerous. In the mid-1980s, a monument was erected in front of the union hall in Sydney listing the names of 304 individuals who had lost their lives at the steel plant.

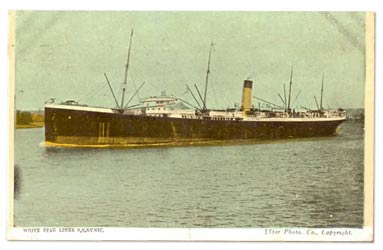

The McLennans had a long history of involvement with Montréal and McGill University, where the world's first organized hockey club, made up of McGill students, played their first game in 1877. The Society for International Hockey Research (SIHR) now note the significance of the game played by James Creighton and several McGill University students at Montreal’s Victoria Skating Rink on March 3rd, 1875. This is the earliest eyewitness account known to the SIHR of a specific game of hockey in a specific place at a specific time, and with a recorded score, between two identified teams. The McLennans had given McGill financial aid since 1881; family members held honourary librarian and governor positions there; and they financed the University's McLennan Traveling Library in 1901, which still operates today. [74] McGill University library is named after Isabella McLennan, eldest sister of Kendall's step-mother, whose bequest largely financed it. Jim's friend Hugh McLennan studied Arts at McGill University between 1905-7, when he was 18 to 20 years old. He then left for Paris to study architecture at l'Ecole des Beaux Arts. He enlisted in the Canadian Field Artillery in 1914 and was killed in action at Ypres, Belgium in 1915. [83, 84] Kendall was almost three years younger than McLennan. He had probably also studied further after high school, and quite possibly at McGill, from about 1907. A friend of Kendall's sister said in Sydney, NS in 1996: " ... [Jim Kendall] and Katharine McLennan's brother Hugh were very close friends and they had, as young men, worked over at the steel plant in summers, and then Hugh was killed. Anyway, Jim – James Kendall – decided he'd see the world so he took a tramp steamer. He found himself in Cape Town and he didn't have any money and he wore his pajamas on the boat. That was his garment on the boat because he was saving his suit for the land. Anyway, he put on the suit and hitched a ride, he wanted to see the diamond fields in South Africa because the tramp steamer was going to be in for a few days, so he had a two or three days off. So he got on this train, and this was quite an offense in South Africa, and he got put in jail and he was desperate ... but he got out and on to the boat and went to Australia." [80]

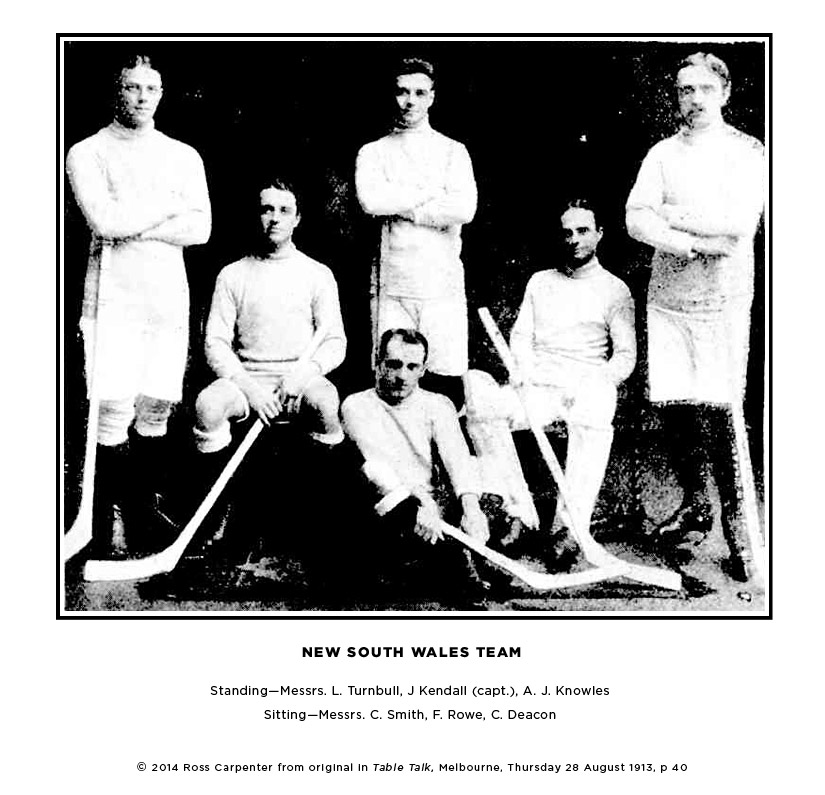

The tramp steamer was the White Star Line SS Runic which originally ran a regular service between Liverpool and Australia via Capetown. However, the Huddardt Parker & Co Line had been absorbed by White Star and others a year or two earlier. Huddardt ran the first service from Vancouver to Sydney, and so Kendall, then a 19 year-old salesman, had probably boarded at Vancouver. He arrived in Sydney via Melbourne on June 26th, 1909, to be greeted by the painful news of his mother's death, two weeks earlier on the 9th. [80] This was the year the Goodall Cup was first contested although, according to the official record, Kendall did not play until two seasons later. [1,2] He was a little over 5-foot 11-inches tall (181 cm), with a 41-inch chest (104 cm), and weighed in at 12 stone 4 lbs (78 kg). He had a dark complexion, brown eyes and hair. [59] He regularly commuted 160 km between Newcastle and Sydney to start game play at 10.15 pm, then returned on the 'Paper Train', as it was commonly known. He played his first game for NSW in 1911 at the age of 22 and he also played on the 1912 and 1913 NSW teams. [1]

Ice hockey in Australia by this time was conducted according to McGill Rules (1879) introduced in Melbourne by 1908, and although Victoria assigned two rovers to tag Kendall, it made little difference. [2] The Cup left Victoria for the first time that year, remaining in NSW for two years, and Kendall was instantly regarded as the best ice hockey player in Australia for years thereafter. The Victorian Interstate Hockey Programme in Melbourne in 1932 reported concern among the Victorians from the time of the first NSW practice session: "Jim Kendall caused consternation and amazement with the Victorian players and selectors by his amazing speed, accuracy and powerful shooting and was virtually a match on his own for the Victorian team." [2] The Sydney Ice Hockey Club had established three local teams in 1911; Ottawa, Corinthians and Wanderers. [2] The name Corinthians, Kendall's team, comes from a little city called Corinth in Greece, known for its wealth and decadence. It means a rich amateur sportsman, especially an amateur yachtsman. Wanderers, was led by State captain Jack Pike, but may have been named after Montréal Wanderers, one of the two Canadian professional teams with whom Kendall is likely to have had some affinity. Yet, it was most likely named after a Western Sydney soccer club called the Wanderers, one of the first registered clubs to play a soccer game in Australia against the King's School's rugby team in 1880. Dunbar Poole was associated with soccer in New South Wales and he played in the 1911 Goodall Cup. Over a century later, a new A-league soccer club was formed in Sydney in 2012, and named in homage to the original Wanderers.

Some say Jim Kendall was Australia's first Canadian ice hockey player but, in fact, he was the second. The first on record was Toronto's Herbert Blatchly (abt 1872 – 1948), captain of the 1st Australian Team in 1906. Nonetheless, skills like Kendall possessed had probably not been seen in Australia up until then. He revolutionised NSW ice hockey through his Canadian training and ability, but Victoria still took the interstate honours 2-1 in 1913, winning the Cup back, even with Kendall opposing them. The Victorian Association lost Brighton IHC in 1912, reduced to just three teams, but it was restored to full strength in 1913 when Brighton IHC was reconstituted. The 1914 season was abandoned immediately war broke and ice hockey in Australia did not resume until 1919 in Melbourne and 1920 in Sydney. [1]

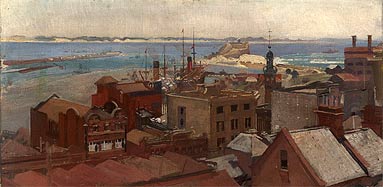

In 1914, Kendall lived at 45 Phillip Street, Sydney, NSW, a short distance from Circular Quay. [91] The terrace building is now heritage protected and presently occupied by Phillips Heritage Restaurant. Kendall had spent two months in the New South Wales Lancers, and then enlisted in the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force. He did that on August 11th, 1914; the day after volunteers were called; the day after his friend Hugh McLennan enlisted in the Canadian Field Artillery. Kendall was 24 years old when he became a soldier in the first infantry to leave the country, while the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) was still being formed. He sailed on P & O Liner Berrima to capture Rabual in German Papua New Guinea, and served there as a Private in the Tropical Unit of B Company, seizing and destroying German wireless stations. [69] There were 117 men in this unit and among them was another young Canadian, Jimmy Bendrodt, who had enlisted the same day as Kendall. He was a roller skater from Victoria, British Columbia who, after attending school in Vancouver, worked his passage to Sydney as a stoker, arriving with only five pound the year after Kendall. Dark, lithe and muscular, he claimed to have been a lumberjack and to hold Canadian roller-skating titles. Appointed manager of the new Imperial Roller Rink, Hyde Park, he soon secured the lease and fostered an exclusive and decorous image that was to characterize all his enterprises. He reopened the building as the 'Imperial Salon De Luxe' early in 1914, a few months before he enlisted, to cater for American dance crazes. [94] A roller rink named Salon de Luxe was established at South Yarra in Melbourne in 1914 (see Robert Jackson).

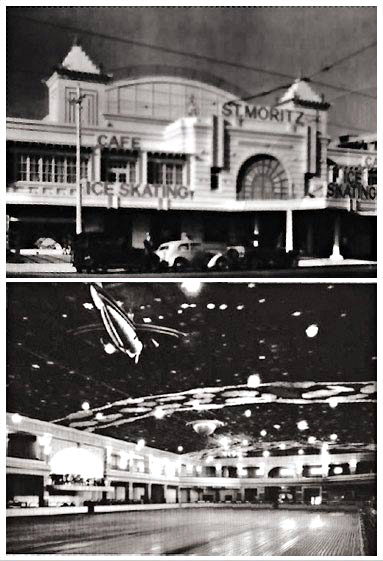

Bendrodt was a racehorse owner-breeder from sometime in the early 1920s, and later owner-operator of the Ice Skating Palais; Sydney's second ice rink. Both these business interests figured in Kendall's future, and it was in the Tropical Unit of this special military force that the pair formed their first association; in 1914 and perhaps earlier. They returned on HMAT Eastern on January 9th, 1915 in charge of prisoners of war, and they were discharged about one week later when the Force's six month period of special service had expired. [59] Neither saw action. Within a few months Kendall received news of the death of his friend, Hugh McLennan, who had been killed in action on the Western Front in late-April. In Sydney the same year, he married Hilda Mary Dibbs (1894 – 1978), daughter of Charles H J Dibbs and Matilda Harris of St Leonards, NSW. [33] Hilda has been described as "a Baroness or something or other, a great socialite in Sydney, Australia". [80] They spent part of the remainder of the war in Canada, probably with Helen and uncle Arthur, and the grieving McLennans. Jim's father enlisted in the Canadian Overseas Expeditionary Force in June 1916. [71] He was Lieutenant Colonel of the 9th Stationary Hospital based at Bramshott Military Hospital, England, for three years between September 1916 and 1919. Bendrodt also returned to Canada and served in the Canadian Expeditionary force in 1918, but he was back in Australia by 1919. The Kendalls had returned by June 1916 and resided at the Criterion Hotel in Newcastle, New South Wales, near the Newcastle GPO. [186] Their son William Ernest Kendall (1916 – 2004) was born there in June 1916. In all probability, it was Kendall who introduced Bendrodt to Australian ice hockey. And it was Kendall who was first to succeed with horse racing.

In 1915, Broken Hill Proprietary Company (BHP, now BHP Billiton) opened its steelworks at Newcastle, NSW, which had a very similar industrial climate to Sydney in Nova Scotia. It dominated the industry nationally for 84 years, employing about 50,000 people by the time it closed in 1993. Kendall was appointed BHP's Chief Mechanical Engineer after he returned from Canada during the war, sometime before 1917. His future business partner, BHP metallurgist Leslie Bradford (1878–1943), was transferred to their Newcastle steelworks the year it opened. Bradford had invented an improved process for treating ores, and he had also perfected the flotation process of separating silver-lead and zinc about 1912. One historian claims it "constitutes perhaps the greatest single metallurgical improvement in the modern era". Also among Kendall's friends was W Nicholson, the owner of racehorse Jack Findlay, ridden by the most acclaimed jockey of the time, W H "Midge" McLachlan. Kendall, Bradford, and a group of friends, punted on the horse, rolling-over their bets on five straight wins between 1919 and 1920. By January 24th, 1920, they had won a small fortune of 15,000 pounds. Kendall and Bradford both resigned from BHP and used their winnings to establish Alloy Steel Syndicate on April 28th, 1920, and a steel foundry in Alexandria, Sydney. Bradford Kendall Ltd was registered as a public company in 1922 with Jim Kendall as Managing Director. BHP attracted Bradford back soon after, and he became their production superintendent, manager of the steelworks in 1924, general manager in Melbourne under Essington Lewis in 1935, and CEO of BHP in 1938. [78] However, Bradford still remained an active director of Bradford Kendall Pty Ltd, by then a major foundry, and he also established Bradford Insulation Ltd in 1940 to manufacture rock-wool from steelworks' slag. [79] Today, BHP Billiton is the world's largest mining company, and its huge expansion around the time Kendall and Bradford departed was jointly financed by the Commonwealth Bank, John Goodall & Co of Melbourne, and a Sydney sharebroker (see John Goodall).

Kendall's company originally made contract castings for general industry, then licensed products in the form of railway couplers and under-carriages in 1926. It excelled in the Great Depression by supplying manganese steel products to the mining industry, and later by manufacturing dredge buckets for the Malayan tin mining industry. It's main railway supply business suffered after the Depression and production changed to armament castings during World War II. It built a foundry for the Commonwealth Government to make cast armour for the Australian-built tank program, starting with aerial bombs, naval gun parts and tank hulls. Then came their design for the world's first one-piece cast tank hull in 1940. It was accepted by the Ministry of Munitions and Bradford Kendall were commissioned to make the Cruiser tank. With Kendall's son at the helm after the war, growth was further boosted through renewal of Australia's neglected railway systems. In 1948, the company listed on the Sydney Stock Exchange, growth surged on into the 1950s, and Bradford Kendall foundries were built in South Australia, Western Australia, Victoria and Queensland. Today, the company is Bradken; Australia's largest combined foundry and heavy engineering group and one of the leading ferrous-casting companies in the world. From its corporate office in Newcastle, it operates 18 specialised manufacturing facilities and five businesses throughout Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom with a 2,800-strong workforce. [78]

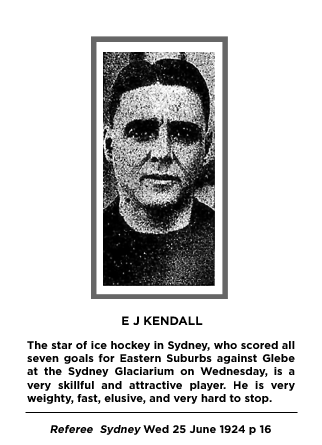

Kendall resumed his hockey career when Sydney Glaciarium re-opened in 1920. It has been said his coaching gave New South Wales a distinct advantage over Victoria, but American hockey star, Charles Uksila, was also a trainer in Sydney this year (see Charles Uksiila). Kendall was a founder and captain of the NSW Eastern Suburbs Ice Hockey Club and coached players such as Jim Brown and Ken Kennedy. These were still early days for Australian ice hockey — the Sydney Glaciarium IHC at the time was comprised of only 35 members. It was renamed Sydney IHC on June 22nd, 1921, operating as the forerunner to the NSW State controlling body. Kendall's club and three others were formed at the same time and team strength went from six to seven players. Seven was consistent with the original Canadian team strength, which didn't reduce to six until 1913 in Nova Scotia, and 1923 on the west coast when the Rover position was dropped. Six men a side was re-introduced to Australia in 1922, and introduced at the Olympic Games in 1924. [2] One of the other new teams was captained by Jack Pike, and another by Leslie Reid (1894–1932), son of Henry Newman Reid. Leslie was Vice President of the first Sydney Glaciarium Ice Hockey Club by 1920 when Pike was president, and it has been said that his hockey skills rivalled those of Kendall. [2] Kendall was not among the local and State team selectors of this era. Leslie Reid, Norm Joseph and Jack Pike were elected by the club in July 1920, May 1921 and again in March 1922. [2] The four new clubs formed on June 22nd, 1921 were:

Eastern Suburbs IHC (7) — Jim Kendall (c), Frank Joseph, W Panter, F Whyte, H Tanner, S Schute, John Lovelace.

South Sydney IHC (6) — T Gibson (c), H Butler, C Fowler, E Hewitt, Dr Murphy, W Power.

Western Suburbs IHC (9) — Jack Pike (c), Carl Kerr, John Kerr, Dr Hamilton, W Store, T Wells, W Webb, J Carpenter, John Lowick.

North Shore IHC (10) — Leslie Reid (c), C Gates, Norm Joseph, H Ives, W Watkins, Reginald Boyden, Henry Hinder, D Cathro, L Cathro, S Green. [2]

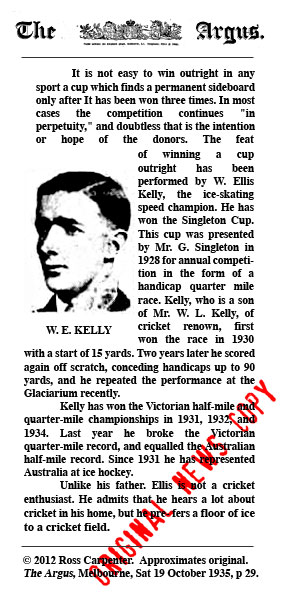

The clubs were also referred to as Easts, Souths, Norths and Wests. Interstate games resumed the next year and New South Wales won the Goodall Cup. Victoria won it back the year after in 1922, then New South Wales dominated, perhaps winning fifteen of the seventeen contests between 1923 and 1946. Victoria tied the 1932 and 1946 series but New South Wales kept custody of the Goodall Cup (see Ted Molony). In 1926, The Argus newspaper in Melbourne reported, "A notable absence from the New South Wales team is J Kendall, who has retired from the game. With the exception of Kenny, the personnel of the New South Wales team is the same as last year, when NSW easily defeated Victoria". [133] Kendall was 37-years-old, but he continued to coach. In 1937, at the age of 48, he returned to coach the new Sydney University Ice Hockey team in the reserve grade showing "that he has lost none of his skill in handling the puck". [541] This club had been formed with members of the four senior clubs who attended the University. The state association hoped it would develop into a fifth senior club and, although it performed credibly, it disbanded in 1938. [1]

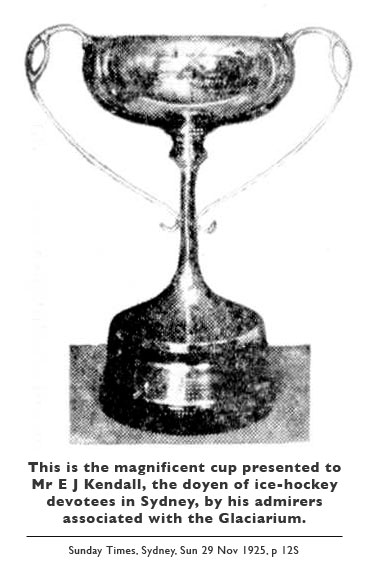

In 1924, the season before he retired, Kendall's Eastern Suburbs again won the New South Wales ice hockey premiership and the Hamilton Trophy. Kendall won the Tintex Cup for the highest scorer with 18 goals, half the total his team scored that season. The manager of the Studebaker factory in Detroit and Cleveland visited here that year and said Kendall was "the equal of any of the American or Canadian players." [566] Jim Kendall was elected the first life member of the NSW Association although he is no longer listed by the New South Wales association. There were a total of four other life members when Jim Barnett, the former State and Glebe goalkeeper, was elected a life member in 1937: E. J. Kendall, D. Poole, N. P. Joseph and C. V. Kerr. Like Kendall, Jim Barnett is no longer listed. [567]

Jim Kendall contributed many years to the sport as a player, coach and administrator from within a few years of its inception in Australia. He was also an accomplished yachtsman and competed regularly in 13 ft and 16 ft skiff racing on Sydney Harbour, and in larger yachts farther abroad. He sailed his skiffs "Iris", "Cibou" and "Oweenee" from the Drummoyne and Port Jackson 16-ft Skiff clubs. He was 1924/25 State champion in Iris on Lake Macquarie, and the E J Kendall Cup at Port Jackson club was named after him early 1930s. These skiffs are unique in the world and peculiar to Australia.

Kendall's son William Ernest 'Bill' Kendall, was a Harvard graduate and represented Australia in 100 metres freestyle swimming at the 1936 Berlin Olympic Games attended by his parents, finishing 5th in the semi-finals with a time of 59.9 seconds and 12th overall. He married Australian figure skating champion Betty Maxwell at Woollahra where his parents lived in 1942, and had two children, James and Brooke. [33]

Jim Kendall was living at Oak Lodge Trelawney Street Woollahra when he died at age 53 on May 5th 1942, [21, 542] the year his son married; the year his 78-year-old father became Lieutenant Governor of Nova Scotia, and moved into Government House, the oldest vice-regal residence in North America. His father retired after 5 years as Lieutenant Governor to his home in Windsor where he died two year later. After Jim's death, his son Bill was appointed Managing Director of Bradford Kendall Ltd and he retired in 1979 after 36 years. Jim's wife Hilda remarried in 1953 to Baron von Nordegg-Rabenau of Austria who had moved to Sydney. The couple were Sydney socialites, oftened photographed at parties, departing overseas, with interior designers, or at art shows. The baron was an Olympic attaché for the 1956 Games in Melbourne. Kendall's sister, Helen, visited Australia twice late in life with her friend, Katherine McLennan, and eventually became a beneficiary of her brother's estate after the death of his wife in 1978 in Sydney. [80] To perpetuate Jim's memory, the 'Jim Kendall Trophy' was presented in 1949 by former NSW Association President, Harold Waddell Hoban and Ken Kennedy's father, Jack. It was awarded to winners of the inter-rink matches between Sydney's Glaciarium and Ice Palais teams.

![]() Eastern Nova Scotia - Prince Edward Island | Map | Sydney - Montréal | Map |

Eastern Nova Scotia - Prince Edward Island | Map | Sydney - Montréal | Map |

Sydney Steelworkers | Undated | COM Henry + Ida | 1888 | Ida - COD | 1909 | S S Runic Ship's List | 1909 |

Jim - Enlistment | 1914 | Hugh McLennan | 1914 | Petersfield | various | Helen at war | c 1918 |

Sydney, NS | 1920 | Horse Race | 1920 | Annual Meeting | 1926 | Cruiser Tank | 1940 | Henry - COD | 1949 |

Historical notes:

[1] Henry Kendall was Lieutenant Governor of the Province of Nova Scotia between November 17th, 1942 and August 12th, 1947; long after his son had left Canada. In fact, Jim died the year of the appointment, so he may not have even heard. Henry was age 78 when sworn in, the oldest to hold this office in the history of Nova Scotia, and one of the oldest in all of Canada. Lieutenant Governors are Royal representatives appointed by the Governor General on the recommendation of the Prime Minister of Canada and the Federal Cabinet. He lived in Government House at Halifax, the oldest vice-regal residence in North America, for almost five years. His political career had commenced at least twenty years earlier, when on June 12th, 1921, he was an unsuccessful Progressive Party candidate for the Federal Riding of Hants, Nova Scotia, in the 14th Parliament. [67] He was succeeded as Lieutenant Governor by John Alexander Douglas McCurdy (1886-1961), the first person to fly an airplane in Canada and a founder of the Royal Canadian Air Force. Henry Kendall died two years later at the age of 85 in Windsor, NS. He was interred with his first wife Ida, brother Arthur, and mother Emily at Hardwood Hill Cemetery, Sydney, NS. [68]

[2] Jim Kendall's uncle, Arthur Samuel Kendall (March 25, 1861 – July 18, 1944), was a physician and political figure in Nova Scotia like his brother. He was a Liberal member representing Cape Breton in the Canadian House of Commons from 1900 to 1904. He graduated from Mount Allison College in 1879, Halifax Medical College in 1881, and Bellevue Hospital Medical School in New York in 1882. He was certified as a Member of the Royal College of Surgeons from Guy's Hospital Medical School in London, England in 1884 and returned to Sydney to establish a medical practice later that year. [73] His younger brother Henry, Jim Kendall's father, was also a practising physician and may have attended some of the same schools. But it was Arthur's time in England that enabled him to see in advance the effects of industrialisation, which in turn shaped his reformist agenda. Arthur served as a town councillor for Sydney in 1888 and ran unsuccessfully for a seat in the House of Commons in 1896. He represented Cape Breton County in the Nova Scotia House of Assembly (MLA) from 1897 to 1900 and from 1904 to 1911. [63] Arthur's association with Cape Breton coal miners built his reputation as the "miners friend'' and someone "for whom the miners had great affection". He did not appear to care unduly about personal wealth or physical appearance. The County of Cape Breton 1979 Centennial Booklet contains a photograph of an elderly Arthur Kendall, unassuming and kindly, wearing a cloth cap and a tattered fur coat that is strapped around his chest and waist, with two stout leather belts — displaying an obvious "unconcern for his sartorial condition." [77]

[3] Simon Fraser (1832–1919), grandfather of former Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser, was born in Pictou, Nova Scotia (map at link above). He grew up there and immigrated to Australia in 1854 at the age of 22, where he bought extensive estates in the Western District of Victoria. There he became a leader of the wealthy wool-growing class known as the squatters, which included the Armytage family. Fraser was elected to the Victorian Legislative Assembly for the seat of Rodney in 1876 where he served until 1883. He was elected to the Victorian Legislative Council, the traditional preserve of the squatters, for South Yarra Province in 1886, and remained a member until 1901. He was a Minister without Portfolio from 1890 to 1892. He was a Victorian delegate to the Imperial Conference in Ottawa, Canada in 1894. Robert Reid, uncle of Henry Newman Reid, was also in Ottawa in May 1894. Reid had arrived the year before, the year Lord Stanley donated the Stanley Cup (see Henry Newman Reid). Fraser was a member of the Constitutional Convention which drafted the Australian Constitution and he was closely related to the family of John Goodall.

[4] Known links between members of the NSW Ice Hockey Association and NSW horse racing at this time include Kendall and W Nicholson; Jimmy Bendrodt (1891–1973), racehorse owner and manager of the Sydney Ice Palais. In 1920, Bendrodt may have been patron of Glaciarium Ice Hockey Club in 1920, the earliest forerunner of the NSW Association. Kendall resumed playing that year and he is on record in 1923 as attending the Association meetings. [2] Bendrodt may have been part of Kendall's racing circle. Bill "Midge" McLachlan (1889 – 1967), who rode Jack Findlay in 1920 and catapulted Kendall and Bradken to success, was great-grandfather of the Freedman brothers. Midge was one of the most acclaimed jockeys of his time. His feature wins included three Melbourne Cups, two Caulfield Cups and two Sydney Cups, and he is widely (though wrongly) celebrated as the first Australian jockey to ride for the royal family in England. In fact, that distinction belongs to his son, William Henry McLachlan (1908 – 1964) or "Young Bill," who died at Randwick in 1964.

[5] NHL Correspondent, Bill Meltzer, writing in April 2008 for the IIHF, claimed Kendall was a 'one-time Montréal Canadiens player'. The Canadiens were founded by J. Ambrose O'Brien on December 4th, 1909, as a charter member of the National Hockey Association, the forerunner to the National Hockey League. Kendall arrived in Australia from Liverpool England in June 1909. He had left Canada at least a year before the club was founded. Meltzer also wrote that Kendall played in the first Goodall Cup in 1909, but he first played in 1911. [1, 2]

[6] In June 2002, the Society for International Hockey Research (SIHR) released an 18-page report concluding that the first ice hockey match was played at the Victoria Skating Rink in downtown Montreal on March 3rd, 1875. The next month, the International Ice Hockey Federation (IIHF) picked Montreal as the birthplace of ice hockey over other Canadian communities — including Kingston, Ontario and the spot near Windsor, NS where many Nova Scotians feel the first game was played. According to both the IIHF and the SIHR, although sports that resembled hockey may have been played in other places before 1875, the first actual game with a puck, nets and a specific set of rules was in Montreal (see Montreal Hockey History at Hockey Heritage).

HENRY CRITCHLEY HINDER (1899 – ) "H Hinder", founding member North Shore IHC, NSW, 1920. Born in 1899 at Summer Hill, Ashfield, NSW, eldest son of Henry V Critchley Hinder (1865–1913) and Ethel Enid Pockley of St Leonards, NSW. Summer Hill is 8 km west of the Sydney CBD. Brother of Francis (Frank) Henry Critchley Hinder (1906–1992), an award-winning Australian painter, sculptor and art teacher who is also known for his camouflage designs in World War II. Like Frank, Henry probably attended his father's alma mater, Newington College, and on moving to the North Shore completed his education at Sydney Church of England Grammar School (SCEG aka Shore School). Frank's biography and work can be viewed at Art Nomad and the Official Website of his estate. [256]

SCEG was founded on May 4th, 1889, an initiative of Bishop Dr Alfred Barry of the Sydney Diocese of the Church of England. The foundation headmaster was Ernest Iliff Robson BA MA (1861–1946). Five years prior in 1884, Robson had been recruited by John MacFarland as inaugural classics teacher for Ormond College, University of Melbourne. He was succeeded by Barney Allen, its vice-master, and in 1895 married Kate Isabel, daughter of Alexander Morrison, headmaster of Melbourne's Scotch College. Ormond and Scotch colleges were closely associated, and Robson no doubt had a hand in the design of the SCEG badge which contains symbols from both schools, notably the four brightest stars of the Southern Cross on an Oxford blue background, first used by Scotch College (see John Grice). This was quite unlike the earlier crests of Sydney Grammar and the University of Sydney which both use the representation of the Cross that appears on the New South Wales State badge. It was a compromise, sitting somewhere between. Robson returned to Melbourne and was appointed classics master at Melbourne Church of England Grammar School in 1901 and acting head in 1905. Next year he became vice-warden and classics tutor at Trinity College, University of Melbourne.

JOHN WARNE LOWICK (1892 – 1969) "J Lowick", founding member Western Suburbs IHC, NSW, 1920. Born April 29th, 1892 at Mosman, NSW, only son of Robert Warne Lowick and Annie Armitage of Sydney. His older sister, Jessie, was born in 1888. Lowick was a 22 year-old, unmarried clerk living with his family at Wakefield Street, North Manly, NSW, when he enlisted on February 8th, 1915, as a bugler in 13th Battalion, 4th Reinforcement, AIF. He served overseas embarking Sydney on board HMAT A9 Shropshire on March 17th 1915. He was a veteran of Gallipoli with the 13th Battalion, where Leo Molloy also fought; then Egypt with 45th Battalion from March 1916, and France from June 1916. His battalion was heavily engaged during the battle of Messines in June, and suffered commensurate casualties. AIF operations switched to the Ypres sector in Belgium and the 45th took part in another major battle near Passchendaele on October 12. Conditions were horrendous; the operation was hastily planned; and thus resulted in failure. Awarded the Military Medal in 1917, "...for his courage at Zonnebeke on 12th October 1917. He went on several occasions and repaired broken wires during a severe enemy barrage and counter attack. His coolness and determination was most marked and his perserverance in his duty enabled communication to be maintained at a critical time. Recommended by Major Stanley Llewellyn Perry MC." Promoted 2nd Lieutenant and Lieutenant in 1918. Moved to Kempsey, NSW and served as Lieutenant 30th Battalion in 1944-5, during World War 2. John Lowick was wed in Sydney in 1927 to Ellen Margaret Grant, daughter of Thomas and Ellen Grant. His wife Ellen died in 1942 at Randwick, and he died in 1969 at Burwood in Sydney. [255]

JOHN ALFRED LOVELACE (1885 – 1969) Probably "J Lovelace", founding member Eastern Suburbs IHC, NSW, 1920. Born in 1885 at Paddington, NSW, eldest son of John Alfred Lovelace and Annie Elizabeth Reece of Sydney. [254]

REGINALD HASLAM BOYDEN (1896 – 1937) "R Boyden", founding member North Shore IHC, captained by Leslie Reid. Born on August 21st, 1896 at Surrey Hills in Victoria, the third son of accountant Frank Ernest Boyden (1858–1930) and Annie "Daisey" George (1864–1943). His brothers were Frank Arthur Stewart (1890–1952); Nicholas Lancelot "Lance" (1893–1972); Paul (abt 1900–1955); Arthur Keeling (1904–1976); and sister Lily, all born in Melbourne. His family moved to 21 Harbor Street in Mosman, on Sydney's Lower North Shore, where the Reids lived from 1917. His father was a senior member of the firm of Boyden Sons & Co, public accountants, and chairman of directors of Rapid Electrical & General Heaters Ltd, established in Sydney in 1921. This company had patented the Rapid Electric Jug and successfully contested a patent infringement in the High Court in 1931, the year after Boyden's father died. [257]

Reginald was a clerk who probably worked in the family accounting practice. He was 5-foot 4-inches tall, 119 pounds in weight, with a 33-inch chest, blue eyes, and fair complexion. He enlisted at the age of 18 on January 7th, 1915 at Liverpool, Sydney and served as a Corporal in B Company, 18 Battalion, AIF. His eldest brother, Stewart, lived with his wife at Darnum near Warragul in West Gippsland, Victoria. He followed his brother and became Major of C Company, 19th Battalion. Reg was shot in the chest by a rifle bullet after two months in action at Gallipoli. Invalided, he returned to Australia after eight months service. Next eldest, Lance, enlisted in November 1916 and became a Lance Corporal in the 4th Battalion in which Leo Molloy was Quartermaster. All three had retured home safely by the end of the war.

The letters of Boyden's mother to his youngest brother Arthur during the Second World War feature in an Australians at War story about a mother who continued to write to her son, not knowing whether he was dead or alive. Arthur had been captured by the Japanese and held as a prisoner of war. He returned from war to find his mother's death had been hastened by grief over two years earlier. Four of five sons had seen action in world wars. [257] Despite the existence of a World War 2 record in his name, Reginald Haslem Boyden died at age 40 on February 19th 1937. The Airlines of Australia Stinson he piloted crashed on the Lamington Park Plateau, near the Queensland - New South Wales border, killing him and 4 others. [418] It was the air crash that made Bernard O'Reilly a hero. O'Reilly's book about the rescue was made into the 1987 TV movie Riddle of the Stinson starring Jack Thompson.

Photographer John Lindt (1845–1926) had a studio in Collins Street, Melbourne and his society, theatre and landscape photographs were highly reputed. He even photographed the capture of the Kelly gang at Glenrowan in Victoria in 1880. Late in the 1880s, he photographed the Chaffey brothers' irrigation works on the Murray River and, on January 8th 1890, he registered copyright of the work in England, with Boyden's father and William Herbert Jones as joint owners (copies held by NLA). A chemist named William Herbert Jones was born in 1887 and his parents lived at 20 Norris Street, Surrey Hills, where the Boydens lived prior to Sydney. Chemistry was central to agricultural science and Jones' father was possibly also a chemist and third owner of the copyright with Lindt and Boyden. [257]

Before they went to Australia, the Canadian-born Chaffey brothers had moved to Kingston on Lake Ontario in 1859. In 1878, they moved again with their father to Riverside, near Los Angeles, California, where they developed an irrigation settlement. Northern Victoria suffered from drought between 1877-84, and Alfred Deakin (1856–1919) visited the California irrigation areas in 1885, with politician John Lamont Dow (1837–1923) and his brother. There they met the Chaffey brothers and this led to the irrigation works on the defunct Victorian pastoral lease, Mildura. Deakin was then a minister in the Service-Berry government and chairman of a royal commission on water supply. John Goodall's family were very influential in California at this time (see Goodall), and Sir Simon Fraser had helped to arrange the Service-Berry coalition, then toured Europe and America in 1883, two years before Deakin. On his return, he undertook pioneering work in artesian water supply with Canadian J S Loughead in 1886, the same year the Chaffeys commenced their Mildura irrigation works (see Fraserland). The Dow brothers were agricultural journalists for The Age and Argus newspaper groups, and behind them lay powerful mercantile and political groups which promoted farming, rather than grazing.

Newsagent Andrew Lambert Reid (1866-1889), brother of Henry Newman Reid after whom Andy Reid was named, began Mildura's first circulating library. Their father, John Lambert Reid, was Trustee of the Public Library (now State of Library Victoria). Andrew Reid Sr died at Mildura when he was just 23 years-old, and was buried on the site of the original Mildura pastoral lease and station. This was where the Chaffey vision for the irrigation colony evolved (see The Chaffey Trail), and Reid had been present when it began in 1886, until his early death there three years later. The Chaffey's work was essential for the emergence of the dried fruit industry in Victoria and South Australia, and provides an enduring legacy in irrigation. Soon after, Reid's uncle Robert, Minister for Defence in the Patterson government, toured Britain and North America on a diplomatic mission to foster closer trade relations. He visited New York, Vancouver, Montréal, Ottawa and Toronto, and met with the successor to Governor-General Lord Stanley, the year the Stanley Cup was first presented. Sir Simon Fraser joined him in Ottawa that year (see Fraserland).

![]() Arthur Boyden | 1919 |

Arthur Boyden | 1919 |

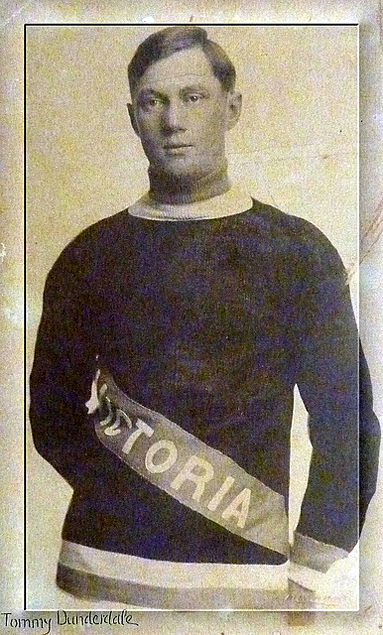

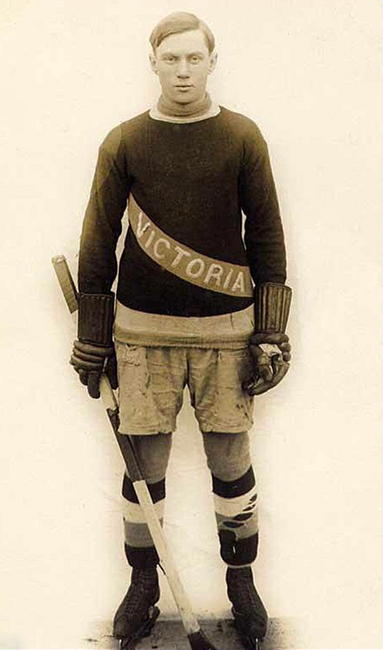

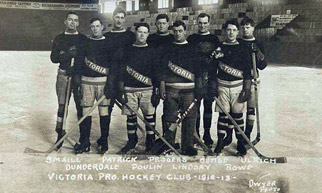

Thomas DUNDERDALE

(1887 - 1960)

BORN ON MAY 6TH, 1887 AT Benalla, an agricultural town in north-eastern Victoria, Australia, to English-born parents, Thomas Dunderdale (1858– ) and Elizabeth Day (1861– ). His older English-born brother was named Henry and his younger sisters, both born in Australia, were Daisy, and Nellie who married Harley Gould. [270] Tommy Dunderdale is the only Australian-born player inducted to the Hockey Hall of Fame, so why has he been overlooked by Australian hockey? Perhaps because he moved to Canada with his family shortly before the first Australian rinks were built. Yet, it seems likely Tommy Dunderdale contributed to the Australian game in ways which are yet to be understood. His family probably emigrated from Lancashire in England and settled at Benalla, originally a pastoral run taken up in 1838 by the squatter-settler Rev Joseph Docker (1793-1865). Known as Benalta Run, the town was laid out on the site in 1846. Docker was an assistant curate to his brother in Southport, Lancashire, who married a Liverpool girl in 1828, then sailed with her for Sydney.

The Dockers built their Melbourne house in Richmond and an investment property named Elwood House at Vautier Street in the original Elwood estate adjoining St Kilda. In August 1871, their son, Frederick George Docker, sold Elwood House to the stock and station agent, John George Dougharty, the grandfather of John Goodall on his mother's side. Goodall's cousin and sporting partner, Elwood Huon, grew up there. Dougharty was a king of the Old Newmarket saleyards in Melbourne, "noted as the best blood horse auctioneer of those days." The Docker's Bontharambo homestead near Wangaratta, still one of the finest in Australia, became famous for its stud of Aberdeen Angus cattle. It remained in the possession of the Docker family after Joseph died, and so it was not surprising they were well-known to the Dougharty and Goodall families. The Goodalls had family in England and they were very prominent in San Francisco at this time, in fact all along the Pacific West Coast where Tommy later played, and so it is quite conceivable the Dunderdales' decision to relocate to North America was related (see Goodall).

Tommy's father was an engineer. He moved the family to Australia about 1885–6, briefly returned to Lancashire in England in 1893, then moved on to Ottawa in Ontario, Canada in 1894, when Tommy was just seven years-old. [270] This was the year after the Stanley Cup had first arrived in May 1893 at Rideau Hall, Lord Stanley's Ottawa residence (Government House); the year Robert Reid and (Sir) Simon Fraser visited as Victorian trade ambassadors (see Fraserland). Their arrival at the same place at the same time was probably more than mere coincidence. Dunderdale was two years older than Jim Kendall, and competed in the same leagues as English-born Herbert Blatchly, who had moved to Toronto some thirteen years earlier. Blatchly was in his early twenties when the young Dunderdale arrived and, a little over a decade later, he became the first Canadian to play ice hockey in Australia, as captain of its very first team. Blatchly's twin-brother Harold and his family had moved from Toronto to Ottawa by 1911. According to the official record, Dunderdale first played organized ice hockey with his Waller Street Public School team when he arrived in Ottawa in 1904. However, he had lived in Ontario for over a decade by then. [270] On the corner of Waller and Theodore (now Laurier Avenue) stood the Rideau Skating Rink, one of the first indoor skating rinks in Canada, which had opened in January 1889. It was no doubt there on the Waller Street corner, at the present location of the Arts Hall of the University of Ottawa, that Dunderdale's school team played hockey.

This rink was built to be finer than Montréal's Victoria Skating Rink where Jim Kendall had almost certainly played before 1909. It was sponsored by Lord Stanley of Stanley Cup fame, who took shares in the project and participated in its formal opening festivities on February 1st, 1889 with a fancy dress carnival. The Stanleys were a Lancashire family like the Dockers and Dunderdales. Lord Stanley became Governor General of Canada in 1888 which, ironically, was the year before the Southport Glaciarium near Liverpool in Lancashire closed at a financial loss after ten years of struggle (see Next Wave). By the time he left for Canada, he had been a Lancashire MP for 21 years and was serving in government as president of the Board of Trade. When he returned in July 1893, the same year the Dunderdales also returned there from Australia, he became Lord Mayor of Liverpool. Lady Stanley had founded the Lady Stanley Institute for Trained Nurses on Rideau Street in 1891, the first nursing school in Ottawa, and she had also been an enthusiastic fan of hockey games at the Rideau Rink, no doubt encouraged by her sons and daughters. Organized ice hockey there began with a game on February 14th, 1889, between members of the Ottawa and Rideau social clubs. Ice hockey pioneers, James Creighton and Philip Ross, trustee of the Stanley Cup, captained the Ottawa and Rideau teams, respectively. The first recorded organized women's ice hockey game was played there on March 8th, 1889, and the first Ontario men's ice hockey championship game on March 7th, 1891, in which Ross helped Ottawa win 5-0 over Toronto St George's.

Since 1904, the Rideau Rink had been used by the Minto Skating Club of Ottawa for several Canadian figure skating championships, although officially the first Canadian championship took place in 1914 in Montréal. By 1922, Dunbar Poole, manager of Sydney Glaciarium in Australia, had become the second instructor at Minto Skating Club. It was an association well outside of Poole's earlier interests in Britain and Europe. It had probably been brought about through his association with Herbert Blatchly and Australia's first organised ice hockey team in Melbourne in 1906, in which Poole also played. Robert Reid and Canadian-born (Sir) Simon Fraser also had established links in Montréal, Ottawa and Toronto at the tail-end of Lord Stanley's tenure as Governor General. Reid was one of Australia's foremost commercial magnates at the time, with offices in London and Glasgow, and an uncle of Henry Newman Reid, who commenced development of Australia's first ice rinks less than a decade later, using venture capital in a manner similar to the financing of the Rideau Skating Rink. The Reid's were well-connected to the imperial authorities in England, including prime minister Primrose; so were the Goodalls (see Goodall); and Fraser's family stretched back at least a century to the early 1800s in Nova Scotia. His Lovat ancestors were there before Canada was even proclaimed (see Fraserland).

In 1905, Dunderdale moved to Winnipeg, Manitoba and played the 1905–06 season with the amateur Winnipeg Ramblers, while attending business college. He returned to Ottawa to play for the Cliffsides club in 1906, before returning to Winnipeg and the senior Winnipeg Maple Leafs. He turned professional at the age of nineteen in the 1906–07 season with Winnipeg Strathconas (aka Winnipeg Maple Leafs and Winnipeg Shamrocks), just two years after he was said to have commenced amateur hockey. However, it is more likely he commenced much earlier, anytime after he first arrived in Canada in 1894. He played three seasons for the Winnipeg franchise, scoring on average more than two points per game, with a majority of goals. In 1904, the Manitoba Hockey Association absorbed the Manitoba & Northwestern Hockey Association league, and included the Kenora Thistles (Rat Portage) team from outside the province. This team was important in Australian hockey history (see Russ Carson). In 1909–10, Dunderdale moved east, and played with the Montréal Shamrocks, first with the Canadian Hockey Association, and later with the National Hockey Association (NHA). That season, he appeared in 15 games overall, and scored 21 goals. He played the 1910–11 season for the Quebec Bulldogs of the NHA, finishing second in team scoring with 13 goals, even though he played only nine of sixteen games, and received 25 penalty minutes.

In 1911, Dunderdale still lived with his family at 250 Young Street in Winnipeg, Manitoba, midway between the eastern and western leagues. [270] He moved further west to the legendary Patrick brothers for the 1911–12 season, and became captain of Victoria Aristocrats (later Victoria Cougars), one of three foundation teams with Vancouver Millionaires and New Westminster Royals in the Patrick's newly-formed Pacific Coast Hockey Association (PCHA), an innovative Canadian league that introduced numerous changes to the sport, and became the first to expand into the United States. The Patricks long had western ties. Their father Joe was a major lumber entrepreneur in British Columbia, where Jimmy Bendrodt was a lumberjack before immigrating to Australia in 1910, just months after Jim Kendall. Later that year, Lester and Frank Patrick gambled on the formation of the Pacific Coast Hockey Association, backed with Patrick lumber money, and Dunderdale spent the rest of his playing career in the west, having played just two seasons east of the Manitoba-Ontario border. He received his first of six First All-Star team selections in the PCHA, scoring 24 goals in 16 games, then 24 goals in each of the next two seasons, again making the First All-Star team in both. It was in August 1912 that a team of Canadian Cadets played a Victorian team at Melbourne Glaciarium [373] and, next month, The Advertiser newspaper in Adelaide announced "The Canadian All-Star Ice Hockey Team are planning to tour Australia in March next." [374]

Meanwhile, the Patricks had negotiated a playoff series for the Stanley Cup between the champions of Canada's east and west leagues. Victoria Arena was sold out in the 1912–13 season for the world series of hockey which Quebec was confident of winning with several top-ranking players of the times. However, Dunderdale's Victoria Aristocrats had plenty of speed, several deadly shooters and a tough defense. They won the first game 7-5; Quebec won the second 6-3; and then Victoria swamped Quebec 6-1 in the third, with Dunderdale and Lester Patrick each scoring two goals. [396, 397] Victoria had won the coast title and then become the first national champions of pro hockey, yet they did not gain possession of the Stanley Cup as the NHA had refused to sanction its use as a world series trophy, despite the Patrick negotiations. In the 1913–14 season Victoria Aristocrats challenged Toronto Arenas (later Blueshirts or just Torontos) for the Stanley Cup. In the best-of-five series Toronto won the opener, the second in overtime, and the third 2-1. [396] Dunderdale scored two goals, and collected 11 penalty minutes from the three games. In the 1914–15 season, he was named in the First All-Star team for the fourth consecutive time, after scoring 17 goals and 10 assists for a total of 27 points from 17 games (see Victoria's Hockey History).

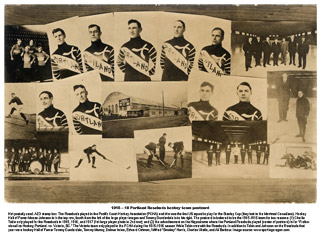

In the 1915–16 season, Dunderdale joined Portland Rosebuds at the same time as Charlie Uksila, the first American-born hockey player to participate in the Stanley Cup playoffs. Dunderdale's scoring average in his first season with the Rosebuds dropped below a point per game for the first time in his career, but they became the first American team to challenge for the Stanley Cup that year. They lost a best-of-five series 3–2 to Montreal Canadiens with Dunderdale playing all of the five games and scoring just two points. The following season, he scored 22 goals in 24 games, returning to his usual offensive output, however, his season was more notable for penalties, setting a league record of 141 minutes. The 1917–18 season was his last in Portland, and he scored 14 goals in 18 games, departing as their leading penalty minute getter and second-most prolific goal scorer, with 50 goals.

| CAREER STATISTICS | REGULAR | PLAYOFFS | ||||||||||

| Season | Club | League | GP | G | A | TP | PIM | GP | G | A | TP | PIM |

| 1905-06 | Winnipeg Ramblers | MIHA | ||||||||||

| 1906-07 | Winnipeg Strathconas | MHL-Pro | 10 | 8 | 0 | 8 | ||||||

| 1907-08 | Winnipeg Maple Leafs | MHL-Pro | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||||||

| 1907-08 | Strathcona-Alberta | MHL-Pro | 5 | 11 | 1 | 12 | 17 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 7 | 3 |

| 1908-09 | Winnipeg Shamrocks | MHL-Pro | 5 | 12 | 6 | 18 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| 1908-09 | Winnipeg Shamrocks | MHL-Pro | 4 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 3 | |||||

| 1909-10 | Montreal Shamrocks | CHA | 3 | 7 | 0 | 7 | 5 | |||||

| 1909-10 | Montreal Shamrocks | NHA | 12 | 14 | 0 | 14 | 19 | |||||

| 1910-11 | Quebec Bulldogs | NHA | 9 | 13 | 0 | 13 | 25 | |||||

| 1911-12 | Victoria Aristocrats | PCHA | 16 | 24 | 0 | 24 | 25 | |||||

| 1911-12 | PCHA All-Stars | Exhib. | 3 | 6 | 0 | 6 | 3 | |||||

| 1912-13 | Victoria Aristocrats | PCHA | 15 | 24 | 5 | 29 | 36 | |||||

| 1912-13 | Victoria Aristocrats | Exhib. | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 8 | |||||

| 1913-14 | Victoria Aristocrats | PCHA | 16 | 24 | 4 | 28 | 34 | |||||

| 1913-14 | Victoria Aristocrats | St-Cup | 3 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 11 | |||||

| 1914-15 | Victoria Aristocrats | PCHA | 17 | 17 | 10 | 27 | 22 | |||||

| 1914-15 | PCHA All-Stars | Exhib. | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| 1915-16 | Portland Rosebuds | PCHA | 18 | 14 | 3 | 17 | 45 | |||||

| 1915-16 | Portland Rosebuds | St-Cup | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 9 | |||||

| 1915-16 | PCHA All-Stars | Exhib. | 3 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 0 | |||||

| 1916-17 | Portland Rosebuds | PCHA | 24 | 22 | 4 | 26 | 141 | |||||

| 1917-18 | Portland Rosebuds | PCHA | 18 | 14 | 6 | 20 | 57 | |||||

| 1918-19 | Victoria Aristocrats | PCHA | 20 | 5 | 4 | 9 | 28 | |||||

| 1919-20 | Victoria Aristocrats | PCHA | 22 | 26 | 7 | 33 | 35 | |||||

| 1920-21 | Victoria Aristocrats | PCHA | 24 | 9 | 11 | 20 | 18 | |||||

| 1921-22 | Victoria Cougars | PCHA | 24 | 13 | 6 | 19 | 37 | |||||

| 1922-23 | Victoria Cougars | PCHA | 27 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 16 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 1923-24 | Saskatoon Crescents | WCHL | 6 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4 | |||||

| 1923-24 | Edmonton Eskimos | WCHL | 11 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 | |||||

| Season | Club | League | GP | G | A | TP | PIM | GP | G | A | TP | PIM |

| GP = Games Played, G = Goals, A = Assists, TP = Total Points, PIM = Penalties In Minutes | ||||||||||||

Dunderdale was 29 years-old when America joined the Allied Forces during World War I, on April 6th, 1917. The United States was never formally a member of the Allies but became a self-styled "Associated Power". It had a small army, but it drafted four million men from a total of twenty-four million draft registrations, and by summer 1918 it was sending 10,000 fresh soldiers to France every day. Dunderdale registered for the draft while at Portland, Oregon, along with Charles and Robert Uksila, but since he played every season, it is unlikely he was called-up. [269] He rejoined the new Victoria Aristocrats in the 1918–19 season, recording only nine points in 20 games in his first season back, but scoring 26 goals in 22 games in the 1919–20 season, en route to his fifth First All-Star team selection. Charles Uksila had joined Vancouver Millionaires. That same year, Jimmy Bendrodt went north to serve in the Canadian Expeditionary Force where Dunderdale and Uksila were playing in his hometowns. Although he had probably come and gone on earlier occasions, he returned to Australia in 1923 with Charles' sister and skating partner, Lena (see Lena Uksila). Dunderdale played three more seasons for Victoria (renamed from Aristocrats to Cougars in the 1921–22 season), playing 75 games in total and scoring 41 points. His scoring averages were a little under a point per game during the 1920–21 and the 1921–22 season. In the 1922–23 season, his last with Victoria, he was limited to only two goals in 27 games. He made the First All-Star Team for the sixth time in 1922. The PCHA folded following the conclusion of the 1922–23 season. Dunderdale played 1923–24 season in the West Coast Hockey League (WCHL), splitting it between the Saskatoon Crescents and the Edmonton Eskimos, and scoring three points in 17 games overall.

Tommy Dunderdale was 5-ft 8-in (1.73 m) and weighed 160 lb (73 kg; 11 st 6 lb). He usually played centre but he was a natural rover, a right-handed player with enough speed to attack and to get back in time to defend. His pro career spanned 1906 until 1924, when he retired at age 36 at the end of the 1923–24 season as the PCHA's leading goal scorer, with 194 goals in total. He was a six-time PCHA First Team All-Star, and league leader for goals in three seasons, and for points in two. In 290 games, Dunderdale scored 225 goals and was noted as an excellent stickhandler and a fast skater. After retiring as a player, he coached and managed teams in Edmonton, Alberta, Los Angeles, and Winnipeg, his hometown. Prior to the Kings' arrival in the Los Angeles area in the 1960s, both the Pacific Coast Hockey League (PCHL) and the Western Hockey League (WHL) had several teams in California, including the PCHL's Los Angeles Monarchs in the 1930s. Charles Miner Goodall lived in LA at the time when its first rink, the Palais de Glace, was built (see Goodall). Charles Uksila performed at the opening.

It is likely Dunderdale maintained an association with the coaching staff of the Blackhawks. One of the NHL Original Six, the Blackhawks were raised in 1926 from Portland Rosebuds. Another future Hall of Famer, Dick Irvin, had been hired as head coach in 1930. Dunderdale and Charles Uksila knew Irvin well. All three were foundation members of the first ever Portland Rosebuds team in 1916. Irvin led the Blackhawks to 24 wins, 17 losses and 3 ties that season, and it is likely he was assisted by Dunderdale. The next year, Winnipeg-born Art Coulter joined the Blackhawks and, the year after, Art's brother Tom returned to Winnipeg from Pittsburg, then signed-up with the Blackhawks in 1933-4, a few seasons before he played for St George in Sydney, Australia (see Tom Coulter). Tom Coulter's sudden appearance in Australian amateur hockey in 1938 was more than chance. The Coulter brothers were born and bred in Dunderdale's hometown, along with another Winnipeg-born player, Hugh Lloyd, who had first captained Victoria in Australia the year before. Dunderdale may have connected Coulter with Bendrodt for the opening of his Ice Palais in Sydney. Bendrodt had been involved with similar arrangements on previous occasions, such as the Uksilas' professional season in Australia in 1923 with Robert Jackson. The Canadian Bears visit that year, from Kenora near Dunderdale's home town, was probably similarly arranged (see Russ Carson).

Even had young Tommy stayed to see it, Australia's fledgling game at the turn of last century could never have developed the artistry he achieved in North American leagues in such short time. Yet, although he was the first of many to leave, a full decade before Australian ice sports had even started, he never really turned his back on his birthplace. He was there behind the scenes in many of Australia's early International relations with North America, from Blatchly's captaincy of the first Australian hockey team in 1906; the Jacksons professional season in New York in 1917-18; the Uksilas in Melbourne in the federation year of Australian ice hockey in 1923; to the opening of the brave new era in Australian ice by the Kenora professionals and Coulter in 1938-9; and possibly even Poole's professional appointment at Minto Skating Club in Ottawa. He was there in the shadows of the coming of age of the Australian game in the 1920s, channeling the new developments which first emerged in the IPHL at Uksila's home town in Houghton, Michigan between 1903 and 1905, then resurfaced later on Canada's West Coast in the Patrick brother's newly-formed PCHA, which Dunderdale and Uksila helped establish. Australia was abreast of these game innovations due to both these men and, although their parallel contributions to Australian ice hockey are not at all obvious many decades on, they ran very deep indeed (see Ted Molony). Any amateur league in the world would have fallen over themselves to similarly access the knowledge and experience Dunderdale and Uksila had accumulated during those years. Moreover, Australian ice sports had benefited from these exchanges long after the actual events, through players and administrators such as Kenora's Russ Carson, who had made Australia their home. Thomas Dunderdale died in Winnipeg on December 15th, 1960, at the age of 73. He was buried at Brookside Cemetery in Winnipeg, and was made an Honoured Member of the Manitoba Hockey Hall of Fame, along with Art Coulter. In 1974, Tommy Dunderdale became the only Australian-born player to be inducted to the Hockey Hall of Fame.

![]() Winnipeg – East to West Coast | Map | Quebec Bulldogs | 1910-11 | Saskatoon Crescents | 1923 |

Winnipeg – East to West Coast | Map | Quebec Bulldogs | 1910-11 | Saskatoon Crescents | 1923 |

Hall of Fame Postcard | 1983 |

Historical Notes:

[1] When Lord Frederick Stanley arrived on Canadian shores in 1888, ready to assume his role as Canada's sixth Governor General, he had never heard of the game of hockey. On February 4th, 1889, Lord and Lady Stanley and their party, which included son Edward and daughter Isobel, observed their first hockey game during the Montreal Winter Carnival. Seated at the Victoria Skating Rink, the Stanleys watched the Montreal Victorias edge the Montreal Hockey Club by a score of 2-1. Lord Stanley enjoyed the new but unusual game, but it was the children who embraced hockey. On returning to Rideau Hall, the Governor General's Ottawa residence, 14-year-old Isobel Stanley formed a women's team, likely the first of its kind, while Edward introduced his brothers Arthur and Algernon to this game of hockey. The three Stanley boys created a team called the Rideau Rebels, comprised of a revolving cast that often included Members of Parliament and senators. As enthusiasm for hockey grew among Lord Stanley's family and friends, so did the Governor General's interest in the game. He was no stranger to the Rideau Rink, and lustily cheered on the excellent Ottawa Hockey Club. When his children encouraged him to sponsor a championship trophy for hockey in Canada, Lord Stanley agreed. At a banquet held at the Russell House Hotel on March 18th, 1892 to honour the Ottawa Hockey Club, a letter was read on behalf of the Governor General by his aide-de-camp, Lord Kilcoursie. 'I have for some time past been thinking that it would be a good thing if there were a challenge cup which should be held from year to year by the champion hockey team in the Dominion,' it began. 'Considering the general interest which the matches now elicit, and in the importance of having the game played fairly and under rules generally recognized, I am willing to give as cup, which shall be held from year to year by the winning team.' The commissioned trophy, purchased in London, England, was engraved with the Stanley family crest on one side and the Governor General's proposed name on the other — Dominion Hockey Challenge Cup. From the moment it arrived at Rideau Hall in May 1893, it was referred to as the Stanley Cup. But by the time the Cup arrived, Lord Stanley was already making plans to leave Canada for England. Upon the unexpected death of his brother, Edward, on April 21, 1893, Lord Stanley immediately succeeded his brother as the Earl of Derby, and was forced to conclude his term as Governor General several months prematurely. The new Earl of Derby never witnessed the presentation of his Cup, won that first year by the Montreal Hockey Club, part of the Montreal Amateur Athletic Association. Therefore, the idea for hockey's championship trophy was born at Rideau Hall in Ottawa, prompted by Stanley's children, who often played on the adjacent Rideau Hall Rink.

Dr Cyril Florance MacGILLICUDDY MM.BS

(1889 - aft 1947)